Abdu-Kinana-Speech.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title First Name Last (Family) Name Officecountry Jobtitle Organization 1 Mr. Sultan Abou Ali Egypt Professor of Economics

Last (Family) # Title First Name OfficeCountry JobTitle Organization Name 1 Mr. Sultan Abou Ali Egypt Professor of Economics Zagazig University 2 H.E. Maria del Carmen Aceña Guatemala Minister of Education Ministry of Education 3 Mr. Lourdes Adriano Philippines Poverty Reduction Specialist Asian Development Bank (ADB) 4 Mr. Veaceslav Afanasiev Moldova Deputy Minister of Economy Ministry of Economy Faculty of Economics, University of 5 Mr. Saleh Afiff Indonesia Professor Emeritus Indonesia 6 Mr. Tanwir Ali Agha United States Executive Director for Pakistan The World Bank Social Development Secretariat - 7 Mr. Marco A. Aguirre Mexico Information Director SEDESOL Palli Karma Shahayak Foundation 8 Dr. Salehuddin Ahmed Bangladesh Managing Director (PKSF) Member, General Economics Ministry of Planning, Planning 9 Dr. Quazi Mesbahuddin Ahmed Bangladesh Division Commission Asia and Pacific Population Studies 10 Dr. Shirin Ahmed-Nia Iran Head of the Women’s Studies Unit Centre Youth Intern Involved in the 11 Ms. Susan Akoth Kenya PCOYEK program Africa Alliance of YMCA Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, 12 Ms. Afrah Al-Ahmadi Yemen Head of Social Protection Unit Social Development Fund Ministry of Policy Development and 13 Ms. Patricia Juliet Alailima Sri Lanka Former Director General Implementation Minister of Labor and Social Affairs and Managing Director of the Socail 14 H.E. Abdulkarim I. Al-Arhabi Yemen Fund for Development Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs 15 Dr. Hamad Al-Bazai Saudi Arabia Deputy Minister Ministry of Finance 16 Mr. Mohammad A. Aldukair Saudi Arabia Advisor Saudi Fund for Development 17 Ms. Rashida Ali Al-Hamdani Yemen Chairperson Women National Committee Head of Programming and Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, 18 Ms. -

Mkapa, Benjamin William

BENJAMIN WILLIAM MKAPA DCL Mr Chancellor, There’s something familiar about Benjamin Mkapa’s story; a graduate joins a political party with socialist leanings, rises rapidly through the establishment then leads a landslide electoral victory, he focuses on education and helps shift the economy to a successful and stable mixed model. He is popular though he does suffer criticism over his military policy from Clare Short. Then after 10 years he steps down, voluntarily. Tell this story to a British audience and few would think of the name Mkapa. Indeed, if you showed his picture most British people would have no idea who he was. This anonymity and commendable political story are huge achievements for he was a leader of a poor African country that was still under colonial rule less than 50 years ago. He’s not a household name because he did not preside over failure, nor impose dictatorial rule, he did not steal his people’s money or set tribal groups in conflict. He was a good democratic leader, an example in a continent with too few. The potential for failure was substantial. His country of 120 ethnic groups shares borders with Mozambique, Congo, Rwanda and Uganda. It ranks 31st in size in the world, yet 1 when it was redefined in 1920 the national education department had three staff. The defeat of Germany in 1918 ended the conflict in its East African colony and creation of a new British protectorate, Tanganyika. In 1961 the country achieved independence and three years later joined with Zanzibar to create Tanzania. -

JULIUS KAMBARAGE NYERERE (1922-) Yusuf Kassam1

The following text was originally published in Prospects: the quarterly review of comparative education (Paris, UNESCO: International Bureau of Education), vol. XXIV, no. 1/2, 1994, p. 247-259. ©UNESCO: International Bureau of Education, 2000 This document may be reproduced free of charge as long as acknowledgement is made of the source. JULIUS KAMBARAGE NYERERE (1922-) Yusuf Kassam1 Julius Nyerere, the former and founding President of the United Republic of Tanzania, is known not only as one of the world’s most respected statesmen and an articulate spokesman of African liberation and African dignity but also as an educator and an original and creative educational thinker. Before launching his political career, he was a teacher, and as a result of his writings on educational philosophy and the intimate interaction between his political leadership and educational leadership for the country, he is fondly and respectfully referred to by the title of ‘Mwalimu’ (teacher) by Tanzanians and others. This is Gillette’s view of him: Indeed, part of Nyerere’s charisma lies in the fact that, before launching his political career with the founding of the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) in 1954, he was a teacher and that his concept of his role as national leader includes constant reassessment, learning and explanation, i.e. education in the broadest sense. Since Independence, and particularly since the threshold year of 1967, Tanzania has been something of a giant in-service seminar, with Nyerere in the professor’s chair (Gillette, 1977). Many features of his educational philosophy have a universal relevance and have inspired many educators and educational and development organizations around the world. -

Julius Nyerere's Philosophy of Education: Implication for Nigeria's

Julius Nyerere’s Philosophy of Education: Implication for Nigeria’s Educational System Reforms by Francis Diana-Abasi Ibanga [email protected] Department of Philosophy, Federal University of Calabar Cross River State, Nigeria. Abstract Julius K. Nyerere’s philosophy of education is one of the most influential and widely studied theories of education. Policy-makers have continued to draw from it for policy re- engineering. In this paper, the Nigerian educational system is examined in the light of the philosophy. This approach is predicated on the informed belief that there are social and historical commonalities between Nigeria and the society of Nyerere’s philosophy. To this end, it is argued that the philosophy holds some important lessons for Nigeria’s education. For this reason, there is need to inject some doses of its principles in the body polity of education in Nigeria. Therefore, the paper identifies three areas where the principles of the philosophy can be practically invaluable for Nigeria, i.e., school financing, curricula development and entrepreneurial education, in and an the final analysis, the paper identifies the linkage between national philosophy of education and national developmental ideology; and argues that a national philosophy of education of any country must be embedded in the national development ideology which the country’s philosophy of education must drive. Key Words: Nyerere, Nigeria, Philosophy of Education, Tanzania, Ujamaa, Self-reliance, Development 109 Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol.9, no.3, June 2016 Introduction Education has been defined in two broad ways. On the one hand, education has been defined as the process by which a society, through certain formal and informal institutions, deliberately transmits its cultural heritage from one generation to another. -

The Anchor of Servant-Leadership: Julius Nyerere and the Virtue Of

THE ANCHOR OF SERVANT-LEADERSHIP Julius Nyerere and the Virtue of Humility PETER MULINGE he emergence of the concept of servant-leadership initiated a new era of moral emphasis in the field of T leadership, which was and still is dominated by self-serving models of leadership. When Robert Greenleaf (1970) conceived servant-leadership as a philosophy and practical model of leadership, he highlighted the need for a better approach to leadership, one that embraces the notion of serving others as the number one priority. He visualized leaders who would take a more a holistic approach to work, promote a sense of community, and to share power in decision making (SanFacon & Spears 2011, p. 115). Fundamentally, servant- leadership is long-term, transformational approach to life and work-in essence, is a way of being that has potential for creating a positive change throughout our society (Spears, 2003, p. 16). In this process, a servant-leader acts with humility to engage himself or herself with others and create a connection that raises the level of motivation and morality in both leader and follower (Northouse, 2016, p. 162). Leaders enable others to act not by holding on to the power they have 195 but by giving it away (Fairholm, 1998; Kouzes & Posner, 1987; Melrose, 1995). Thus, the fervent power of servant- leadership is communicated by sharing power and involving followers in planning and decision-making (Bass, 1990). According Maxwell (1998), only secure leaders give power to others (p. 121). The essence of servant-leadership is to bring out the best in others by meeting their needs. -

Joycebanda Fri, 4/23 10:10AM 46:27

joycebanda Fri, 4/23 10:10AM 46:27 SUMMARY KEYWORDS malawi, women, parliament, president, people, election, female, leaders, msu, left, joyce banda, world, country, support, leadership, fight, men, africa, african, years SPEAKERS Russ White, Joyce Banda, Michael Wahman R Russ White 00:00 This is MSU today. Here's Russ white. Well, it's a pleasure to welcome MSU, Assistant Professor of Political Science and core faculty in the African Studies Center, Michael Wahman to MSU. Today, Michael, great to see you. M Michael Wahman 00:16 Thank you so much, Russell, and thank you for inviting me. R Russ White 00:18 This is exciting. We're going to hear your conversation with former Malawi president, Dr. Joyce Banda here in a minute. But before we get to that, let's set the scene a little bit in general, describe what your research interests are. M Michael Wahman 00:32 Yeah, so my research is focusing on African democracy more broadly. And I'm particularly interested in issues related to elections and how you arrange free fair and credible elections on the African continent. I've studied Malawi for many years. And actually, I've observed several Malawi in elections, including the one where Joyce Banda stood for re election in 2014. joycebanda Page 1 of 16 Transcribed by https://otter.ai R Russ White 01:01 So now talk about this particular research project that is going to lead into this conversation with Dr. Banda. M Michael Wahman 01:08 Yes. So I've had a conversation with Dr. -

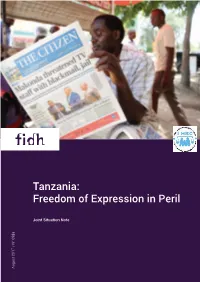

Tanzania: Freedom of Expression in Peril

Tanzania: Freedom of Expression in Peril Joint Situation Note August 2017 / N° 698a August Cover photo: A man reads on March 23, 2017 in Arusha, northern Tanzania, the local English-written daily newspaper «The Citizen», whose front title refers to the sacking of Tanzanian information Minister after he criticised an ally of the president. Tanzania’s President, aka «The Bulldozer» sacked his Minister for Information, Culture and Sports, after he criticised an ally of the president: the Dar es Salaam Regional Commissioner who had stormed into a television station accompanied by armed men. © STRINGER / AFP FIDH and LHRC Joint Situation Note – August 1, 2017 - 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction..........................................................................................................................2 I. Dissenting voices have become targets of the authorities..........................................5 II. Human Rights Defenders and ordinary citizens are also in the sights of the authorities...........................................................................................................................10 Recommendations.............................................................................................................12 Annex I – Analysis: Tools for repression: the Media Services Act and the Cybercrimes Act.................................................................................................................13 Annex II – List of journalists and human rights defenders harassed..........................17 -

Reading Nkrumah and Nyerere's Pan-African Epistemology

Benjamin: Decolonizing Nationalism: Reading Nkrumah and Nyerere’s Pan-Afric INDIA, CHINA AND AMERICA INSTITUTE 1549 CLAIRMONT ROAD, SUITE 202 ● DECATUR, GA 30033 USA WWW.ICAINSTITUTE.ORG Decolonizing Nationalism: Reading Nkrumah and Nyerere’s Pan-African Epistemology Jesse Benjamin Journal of Emerging Knowledge on Emerging Markets Volume 3 November 2011 Published by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University, 2011 1 Journal of Emerging Knowledge on Emerging Markets, Vol. 3 [2011], Art. 14 Decolonizing Nationalism: Reading Nkrumah and Nyerere’s Pan-African Epistemology Jesse Benjamin Kennesaw State University Journal of Emerging Knowledge on Emerging Markets Volume 3 November 2011 his essay explores intellectual history and epistemological transformation, focusing on the middle part of the Twentieth Century – the 1920s to the 1970s -- and Tparticularly on two of the period’s principal African thinkers, Kwame Nkrumah and Julius K. Nyerere. It examines important themes in some of the major writings of these two famous leaders of African resistance to colonialism. After prolonged anti-colonial struggle and maneuver, both became leaders of independent countries, Nkrumah of Ghana in 1957, and Nyerere of Tanganyika in 1961.1 Both were also important scholars, with numerous influential publications. In my research of their thoughts and ideas, several seemingly contradictory themes emerged. While they remain two of the most important African nationalist leaders in history, I argue that both also sought critical and practical perspectives beyond nationalism, and beyond subordination within the capitalist world system. Both were quick to realize the limitations of ‘independence’ for their former colonies cum states, even before this was fully [formally] achieved. They were therefore critical of the specter of neo-colonialism, and espoused versions of Pan-Africanism. -

Modern African Leaders

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 446 012 SO 032 175 AUTHOR Harris, Laurie Lanzen, Ed.; Abbey, CherieD., Ed. TITLE Biography Today: Profiles of People ofInterest to Young Readers. World Leaders Series: Modern AfricanLeaders. Volume 2. ISBN ISBN-0-7808-0015-X PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 223p. AVAILABLE FROM Omnigraphics, Inc., 615 Griswold, Detroit,MI 48226; Tel: 800-234-1340; Web site: http: / /www.omnigraphics.com /. PUB TYPE Collected Works General (020)-- Reference Materials - General (130) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS African History; Biographies; DevelopingNations; Foreign Countries; *Individual Characteristics;Information Sources; Intermediate Grades; *Leaders; Readability;Secondary Education IDENTIFIERS *Africans; *Biodata ABSTRACT This book provides biographical profilesof 16 leaders of modern Africa of interest to readersages 9 and above and was created to appeal to young readers in a format theycan enjoy reading and easily understand. Biographies were prepared afterextensive research, and this volume contains a name index, a general index, a place of birth index, anda birthday index. Each entry providesat least one picture of the individual profiled, and bold-faced rubrics lead thereader to information on birth, youth, early memories, education, firstjobs, marriage and family,career highlights, memorable experiences, hobbies,and honors and awards. All of the entries end with a list of highly accessiblesources designed to lead the student to further reading on the individual.African leaders featured in the book are: Mohammed Farah Aidid (Obituary)(1930?-1996); Idi Amin (1925?-); Hastings Kamuzu Banda (1898?-); HaileSelassie (1892-1975); Hassan II (1929-); Kenneth Kaunda (1924-); JomoKenyatta (1891?-1978); Winnie Mandela (1934-); Mobutu Sese Seko (1930-); RobertMugabe (1924-); Kwame Nkrumah (1909-1972); Julius Kambarage Nyerere (1922-);Anwar Sadat (1918-1981); Jonas Savimbi (1934-); Leopold Sedar Senghor(1906-); and William V. -

East African Community (EAC) and the Southern African Development Community SADC

REGULATING RESIDENCE AND EMPLOYMENT IN EAST AFRICA- LESSONS LEARNED BY MR. PINIEL O. MGONJA, ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF IMMIGRATION (TANZANIA) PRESENTATION TO THE INTERNATIONAL DIALOGUE ON MIGRATION – INTERSESSIONAL WORKSHOP ON FREE MOVEMENT OF PERSONS IN REGIONAL INTERGRATION PROCESSES GENEVA, SWITZERLAND, 18-19 JUNE 2007. 1 INTRODUCTORY REMARKS • Tanzania is a member of the East African Community (EAC) and the Southern African Development Community SADC. • EAC Countries are Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda, with a total population of about 98.3 million. • Cooperation in East Africa has a long history, from the colonial era. In 1947 the EAC had already established the East African Customs Union. • Mwalimu Julius Nyerere, the first President of Tanzania proposed to delay Tanganyika’s independence so that Kenya and Uganda could join the latter to move to independence as a single entity. 2 • The first EAC was established on 1967. • At the time of its demise in 1977 EA was already in the common market. • East Africans moved more or less freely in the Region. • The current EAC draws its strength from lessons learnt from the defunct 1967-1977EAC. • Experience tells that a strong and sound EAC must be people centred. 3 THE MAP OF THE EAC 4 REVIVAL OF EAC • The EAC Treaty which was signed in 1999 specifies four main stages of the integration process namely Customs Union, Common Market, Monetary Union and Political federation. 5 FREEDOM OF MOVEMENT IN EAC • Article 104 of the East African Treaty, the partner states agreed to adopt measures to achieve the free movement of persons, labour and services and to ensure the enjoyment of the right of establishment and residence of their citizens within the Community. -

Tanzania: an 8-Point Human Rights Agenda for Change

Tanzania: An 8-point Human Rights Agenda for Change Index number: AFR 56/4152/2021 WHO WE ARE Amnesty International is a movement of more than 10 million people which mobilizes the humanity in everyone and campaigns for change so that we can all enjoy our human rights. Out of the 10 million, Tanzania has a strong base of 25,955 members and supporters. Our vision is of a world where those in power keep their promises, respect international law and are held to account. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest, or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and individual donations. We believe that acting in solidarity and compassion with people everywhere can change our societies for the better. BACKGROUND On 17 March 2021, President John Magufuli died from heart complications and on 19 March, Samia Suluhu Hassan was sworn in as Tanzania’s first female president from the role of vice president. John Pombe Magufuli was the fifth president of Tanzania, serving from 2015 until his death in 2021. The Late President began his second term in office in November 2020 following a controversial election on 28 October, the same year. This was Tanzania’s sixth general election since the reintroduction of the multi-party system in 1992. Members of civil society and opposition groups accused security forces of using excessive force, including live ammunition, and allegedly killing at least 22 people in the electioneering period. According to lawyers acting for opposition parties, at least 77 opposition leaders and supporters were also arbitrarily detained and released days after the National Electoral Commission announced the elections’ results. -

Julius Nyerere: the Intellectual Pan-Africanist and the Question of African Unity

JULIUS NYERERE: THE INTELLECTUAL PAN-AFRICANIST AND THE QUESTION OF AFRICAN UNITY David Mathew Chacha DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGES AND LINGUISTICS, EGERTON UNIVERSITY, P.O.BOX 536, NJORO, KENYA. Email:[email protected] Julius Nyerere stands out as an epitome in whom a bold experiment was made to give content and meaning to Tanzania’s independence. His passionate conviction was that the case of pan-African freedom was the only legitimate determination of all political action by the political African elites. To him, pan-Africanism meant self –determination in all matters; economic, political, social, ideological and cultural. To demonstrate this he made a cultural choice by adopting an indigenous language, Swahili as both the national and official language. In so doing Nyerere recognized the role of language in the development of cultural authenticity and national unity. This not only facilitated national integration in an otherwise complex multilingual republic of Tanzania but also as a way of asserting independence from political economic and most importantly cultural domination. African intellectuals and literary icons, notably, Chinua Achebe, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Wole Soyinka, Ali Mazrui, Okot p’Bitek,etc have made passionate pleas for a cultural re-awakening, which they see as a first step towards social political and economic growth. Otherwise globalization is not only threatening to marginalize Africa but is also throwing it into a state of confusion as it tries to blend traditional values with western traditions, which to a large extent are incompatible. This paper proposes to draw from Nyereres bold experiment to make a case for the African renaissance and the quest to not only discover itself and uphold its identity but also to appreciate the inherent power enshrined in its cultural heritage.