Understanding Comics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cerebus Rex II: the Second Half

Cerebus Rex II: The Second Half Hello, and welcome to Cerebus Rex II. Written by the Cerebus Fangirl and part by Daniel, it summarizes the second half of Cerebus from issue #150 to #300. It can be found on the internet at http://www.cerebusfangirl.com/rex/ Flight Issue #151 : The novel opens with Cirin in the Papal Library of the Eastern Church looking for books on the One True Ascension. The books that don't meet her criteria are thrown in the Furnaces. So far no books meet her requirements. The demon Khem realizes it has no reason to exist any longer. So it turns into itself and disappears. Cerebus is creating bloody hell in the streets of Iest. Cirin refuses to believe her troops that it is indeed Cerebus. The Judge appears to Death and tells it that it is not Death but a lesser Demon. Death ceases to exist. Lord Julius is sign briefly. Issue #152 : Cerebus fights more Cirinists and (male) on lookers start cheering for "the Pope." They start talking back to the Cirinists. General Norma Swartskof telepathically shows Cirin what Cerebus has been doing. The Black Blossom Lotus magic charm is in the Feld River, the magic leaves it's form and turns into a narrow band of light (the blossom disappears) and two coins that are over 1,400 years old start spinning together in a circle. The report from Cirin is to take Cerebus alive. The General thinks otherwise and orders him KILLED. Issue #153 : Cerebus climbs to a balcony and urges the citizens of Iest that it is the time for Vengeance, for them to grab a weapon, to take back their city and to kill the Cirinists. -

Download This PDF File

Editor: Henry Reichman, California State University, East Bay Founding Editor: Judith F. Krug (1940–2009) Publisher: Barbara Jones Office for Intellectual Freedom, American Library Association ISSN 1945-4546 March 2013 Vol. LXII No. 2 www.ala.org/nif Filtering continues to be an important issue for most schools around the country. That was the message of the American Association of School Librarians (AASL), a division of the American Library Association, national longitudinal survey, School Libraries Count!, conducted between January 24 and March 4, 2012. The annual sur- vey collected data on filtering based on responses to fourteen questions ranging from whether or not their schools use filters, to the specific types of social media blocked at their schools. AASL survey The survey data suggests that many schools are going beyond the requirements set forth by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in its Child Internet Protection explores Act (CIPA). When asked whether their schools or districts filter online content, 98% of the respon- dents said content is filtered. Specific types of filtering were also listed in the survey, filtering encouraging respondents to check any filtering that applied at their schools. There were in schools 4,299 responses with the following results: • 94% (4,041) Use filtering software • 87% (3,740) Have an acceptable use policy (AUP) • 73% (3,138) Supervise the students while accessing the Internet • 27% (1,174) Limit access to the Internet • 8% (343) Allow student access to the Internet on a case-by-case basis The data indicates that the majority of respondents do use filtering software, but also work through an AUP with students, or supervise student use of online content individually. -

Am Yisrael: a Resource Guide to Exploring the Many Faces of the Jewish People

Am Yisrael: A Resource Guide to Exploring the Many Faces of the Jewish People Prepared by Congregation Beth Adam and OurJewishCommunity.org with support from The Jewish Foundation of Cincinnati Table of Contents A Letter to Grownups ....................................................... Page 1 Am Yisrael: One Big Jewish Family ...................................... Page 2 Where Jews Live .............................................................. Page 3 What Jews Look Like ......................................................... Page 4 What Jews Wear ............................................................... Pages 5-8 What Jews Eat ................................................................ Page 9 Fun Jewish Recipes from Around the World ........................... Pages 10-12 I Love Being Jewish ......................................................... Page 13 Discussion Generating Activities ........................................ Pages 14-15 Discussion Questions ....................................................... Page 16 Jewish Diversity Songs ..................................................... Page 17 Coloring Book Pages ........................................................ Pages 18-29 Acknowledgments .......................................................... Page 30 Letter to Grownups When you think of Jews, what do you picture? What do they eat? What language do they speak? How do they dress? What makes them unique? There are so many ways to be Jewish, and so many different Jewish cultures around the world. -

A Dark Heresy Supplement by C.S. Barnhart -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

The K’oTal SySTem The K’otal System A Dark Heresy Supplement By C.S. Barnhart Valkan and related material based on ideas and work by Nolan Allen Featuring the Artwork of: Nolan Allen, Scott Vancil, Dan Mehling, Andrew Best, Michael Zug, Hal Case, Robert Schoolcraft, Bradley K McDevitt, Shane “VShane” Colclough, Scott Xie, Richard Aidley, Luis Peres, H. Haddaway, Richard Spake, Marciej Zagorski. Some Artwork used with permission and provided by: Shaman Stock Art, Octivirate Entertainment, Otherworld Creations Inc, Team Frog Studios, The Forge Studios, Reality Deviant Publications & Postmortem Studios. Maps of K’otal from Landescapes by Keith Curtis of Empty Room Studios Publishing. All rights, trademarks and copyrights of the art in this publication, save for the Warhammer 40,000 Role Play logo remain the property of the artists and companies listed above. Maps of Calixis Sector on pages 10-11 by Darius Hinks, Andy Law and Mark Raynor for Black Industries for original publication in Dark Heresy Core Rules. Used here only for reference and no claims to ownership is intended. Unofficial 1 The K’oTal SySTem SECTION PAGE Introduction 3 Planetary Data 4 K’otal Overview 5 Persons of Note 8 Star Maps 10 Locations of Note 12 K’otal Map 14 K’otal Bestiary 16 New Origins 20 New Alternate Career Ranks 27 Armoury: Valkan Weapons 38 Armoury: Vehicles 40 Armoury: Gear 44 Armoury: Valkan Weapons Chart 45 New Rules: Plains of Ice and Snow 46 New Rules: Starvation and Dehydration 48 New Rules: Exhaustion 48 New Skills 49 Index 50 2 The K’oTal SySTem What is K’otal? In a word, I don’t really know. -

Regional Oral History Off Ice University of California the Bancroft Library Berkeley, California

Regional Oral History Off ice University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Richard B. Gump COMPOSER, ARTIST, AND PRESIDENT OF GUMP'S, SAN FRANCISCO An Interview Conducted by Suzanne B. Riess in 1987 Copyright @ 1989 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West,and the Nation. Oral history is a modern research technique involving an interviewee and an informed interviewer in spontaneous conversation. The taped record is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The resulting manuscript is typed in final form, indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between the University of California and Richard B. Gump dated 7 March 1988. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Azazel Historically, the Word Azazel Is an Idea and Rarely an Incarnate Demon

Azazel Historically, the word azazel is an idea and rarely an incarnate demon. Figure 1 Possible sigil of Azazel. Modern writings use the sigil for the planet Saturn as well. Vayikra (Leviticus) The earliest known mention of the word Azazel in Jewish texts appears in the late seventh century B.C. which is the third of the five books of the Torah. To modern American ( וַיִּקְרָ א ) book called the Vayikra Christians, this books is Leviticus because of its discussion of the Levites. In Leviticus 16, two goats are placed before the temple for selection in an offering. A lot is cast. One Goat is then sacrificed to Yahweh and the other goats is said to outwardly bear all the sends of those making the sacrifice. The text The general translation .( לַעֲזָאזֵל ) specifically says one goat was chosen for Yahweh and the for Az azel of the words is “absolute removal.” Another set of Hebrew scholars translate Azazel in old Hebrew translates as "az" (strong/rough) and "el" (strong/God). The azazel goat, often called the scapegoat then is taken away. A number of scholars have concluded that “azazel” refers to a series of mountains near Jerusalem with steep cliffs. Fragmentary records suggest that bizarre Yahweh ritual was carried out on the goat. According to research, a red rope was tied to the goat and to an altar next to jagged cliff. The goat is pushed over the cliff’s edge and torn to pieces by the cliff walls as it falls. The bottom of the cliff was a desert that was considered the realm of the “se'irim” class of demons. -

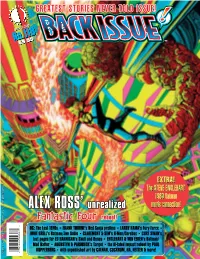

ALEX ROSS' Unrealized

Fantastic Four TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. All Rights Reserved. No.118 February 2020 $9.95 1 82658 00387 6 ALEX ROSS’ DC: TheLost1970s•FRANK THORNE’sRedSonjaprelims•LARRYHAMA’sFury Force• MIKE GRELL’sBatman/Jon Sable•CLAREMONT&SIM’sX-Men/CerebusCURT SWAN’s Mad Hatter• AUGUSTYN&PAROBECK’s Target•theill-fatedImpact rebootbyPAUL lost pagesfor EDHANNIGAN’sSkulland Bones•ENGLEHART&VON EEDEN’sBatman/ GREATEST STORIESNEVERTOLDISSUE! KUPPERBERG •with unpublished artbyCALNAN, COCKRUM, HA,NETZER &more! Fantastic Four Four Fantastic unrealized reboot! ™ Volume 1, Number 118 February 2020 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST Alex Ross COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Brian Augustyn Alex Ross Mike W. Barr Jim Shooter Dewey Cassell Dave Sim Ed Catto Jim Simon GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Alex Ross and the Fantastic Four That Wasn’t . 2 Chris Claremont Anthony Snyder An exclusive interview with the comics visionary about his pop art Kirby homage Comic Book Artist Bryan Stroud Steve Englehart Roy Thomas ART GALLERY: Marvel Goes Day-Glo. 12 Tim Finn Frank Thorne Inspired by our cover feature, a collection of posters from the House of Psychedelic Ideas Paul Fricke J. C. Vaughn Mike Gold Trevor Von Eeden GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: The “Lost” DC Stories of the 1970s . 15 Grand Comics John Wells From All-Out War to Zany, DC’s line was in a state of flux throughout the decade Database Mike Grell ROUGH STUFF: Unseen Sonja . 31 Larry Hama The Red Sonja prelims of Frank Thorne Ed Hannigan Jack C. Harris GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Cancelled Crossover Cavalcade . -

Afrofuturism: the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture

AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISM Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 1 5/22/13 3:53 PM Copyright © 2013 by Ytasha L. Womack All rights reserved First edition Published by Lawrence Hill Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism : the world of black sci-fi and fantasy culture / Ytasha L. Womack. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 (trade paper) 1. Science fiction—Social aspects. 2. African Americans—Race identity. 3. Science fiction films—Influence. 4. Futurologists. 5. African diaspora— Social conditions. I. Title. PN3433.5.W66 2013 809.3’8762093529—dc23 2013025755 Cover art and design: “Ioe Ostara” by John Jennings Cover layout: Jonathan Hahn Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN Interior art: John Jennings and James Marshall (p. 187) Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 I dedicate this book to Dr. Johnnie Colemon, the first Afrofuturist to inspire my journey. I dedicate this book to the legions of thinkers and futurists who envision a loving world. CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................. ix Introduction ............................................................................ 1 1 Evolution of a Space Cadet ................................................ 3 2 A Human Fairy Tale Named Black .................................. -

Dragon Magazine #158

S PECIAL ATTRACTIONS Issue #158 Vol. XV, No. 1 9 Weve waited for you: DRAGONS! June 1990 A collection of lore about our most favorite monster. The Mightiest of Dragons George Ziets Publisher 10 In the D&D® game, no one fools with the dragon rulers and lives for James M. Ward long. Editor A Spell of Conversation Ed Friedlander Roger E. Moore 18 If youd rather talk with a dragon than fight it, use this spell. The Dragons Bestiary The readers Fiction editor Barbara G. Young 20 The gorynych (very gory) and the (uncommon) common dragonet. Thats Not in the Monstrous Compendium! Aaron McGruder Assistant editor 24 Remember those neutral dragons with gemstone names? Theyre 2nd Dale A. Donovan Edition now! Art director Larry W. Smith O THER FEATURES Production staff The Game Wizards James M. Ward Gaye OKeefe Angelika Lokotz 8 Should we ban the demon? The readers respondand how! Subscriptions Also Known As... the Orc Ethan Ham Janet L. Winters 30 Renaming a monster has more of an effect than you think. U.S. advertising The Rules of the Game Thomas M. Kane Sheila Gailloreto Tammy Volp 36 If you really want more gamers, then create them! The Voyage of the Princess Ark Bruce A. Heard U.K. correspondent 41 Sometimes its better not to know what you are eating. and U.K. advertising Sue Lilley A Role-players Best Friend Michael J. DAlfonsi 45 Give your computer the job of assistant Dungeon Master. The Role of Computers Hartley, Patricia and Kirk Lesser 47 The world of warfare, from the past to the future. -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

Turkish Literature from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Turkish Literature

Turkish literature From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Turkish literature By category Epic tradition Orhon Dede Korkut Köroğlu Folk tradition Folk literature Folklore Ottoman era Poetry Prose Republican era Poetry Prose V T E A page from the Dîvân-ı Fuzûlî, the collected poems of the 16th-century Azerbaijanipoet Fuzûlî. Turkish literature (Turkish: Türk edebiyatı or Türk yazını) comprises both oral compositions and written texts in the Turkish language, either in its Ottoman form or in less exclusively literary forms, such as that spoken in the Republic of Turkey today. The Ottoman Turkish language, which forms the basis of much of the written corpus, was influenced by Persian and Arabic and used the Ottoman Turkish alphabet. The history of the broader Turkic literature spans a period of nearly 1,300 years. The oldest extant records of written Turkic are the Orhon inscriptions, found in the Orhon River valley in central Mongolia and dating to the 7th century. Subsequent to this period, between the 9th and 11th centuries, there arose among the nomadic Turkic peoples of Central Asia a tradition of oral epics, such as the Book of Dede Korkut of the Oghuz Turks—the linguistic and cultural ancestors of the modern Turkish people—and the Manas epic of the Kyrgyz people. Beginning with the victory of the Seljuks at the Battle of Manzikert in the late 11th century, the Oghuz Turks began to settle in Anatolia, and in addition to the earlier oral traditions there arose a written literary tradition issuing largely—in terms of themes, genres, and styles— from Arabic and Persian literature. -

The Story of Architecture

A/ft CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY FINE ARTS LIBRARY CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 924 062 545 193 Production Note Cornell University Library pro- duced this volume to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. It was scanned using Xerox soft- ware and equipment at 600 dots per inch resolution and com- pressed prior to storage using CCITT Group 4 compression. The digital data were used to create Cornell's replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Stand- ard Z39. 48-1984. The production of this volume was supported in part by the Commission on Pres- ervation and Access and the Xerox Corporation. Digital file copy- right by Cornell University Library 1992. Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/cletails/cu31924062545193 o o I I < y 5 o < A. O u < 3 w s H > ua: S O Q J H HE STORY OF ARCHITECTURE: AN OUTLINE OF THE STYLES IN T ALL COUNTRIES • « « * BY CHARLES THOMPSON MATHEWS, M. A. FELLOW OF THE AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS AUTHOR OF THE RENAISSANCE UNDER THE VALOIS NEW YORK D. APPLETON AND COMPANY 1896 Copyright, 1896, By D. APPLETON AND COMPANY. INTRODUCTORY. Architecture, like philosophy, dates from the morning of the mind's history. Primitive man found Nature beautiful to look at, wet and uncomfortable to live in; a shelter became the first desideratum; and hence arose " the most useful of the fine arts, and the finest of the useful arts." Its history, however, does not begin until the thought of beauty had insinuated itself into the mind of the builder.