The Subjective Perspective; Aspects of Point of View in Modern Drama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anatomy of a State Security Case the “Victorious Sect” Arrests

Egypt Anatomy of a HUMAN State Security Case RIGHTS WATCH The “Victorious Sect” Arrests December 2007 Volume 19, no. 9(e) Anatomy of a State Security Case The “Victorious Sect” Arrests Summary ................................................................................................................. 1 Methodology ...........................................................................................................7 Background ............................................................................................................ 8 Political opposition and violence in Egypt .......................................................... 8 Egypt’s State Security Investigations.................................................................. 9 The Emergency Law...........................................................................................10 Proposed New Counterterrorism Law................................................................. 14 The Case of the “Victorious Sect”........................................................................... 15 The Announcement of the “Victorious Sect” Arrests .......................................... 15 The Actual Arrests .............................................................................................18 Detention, Torture, and Confessions .................................................................32 Prosecution Dropped ........................................................................................50 The Timing: A Connection to Egypt’s Emergency Law?........................................56 -

Ceramics Monthly O

APRIL 1957 • 50c Igl V • g H i i i i PUT \ / i ~,,~ii~,,~,,,,,~,~,,~,~,,~,,,~ ,~, :,~ ~ ~ :i/ii~i~i~ iiiiii'i~iiii~,~,~'~i~ili!!!~!~i:~...... i SPECIAL INTRODUCTORY OFFER! The materials used in Re-Ward's BRUSH-ON GLAZES are much more expensive than those used in ordinary glazes, and you will recognize this immediately. Because we want you to try them, your dealer FOR A LIMITED TIME ONLY will allow you 10¢ off the regular price for each jar. 10¢ OFF! See your dealer TODAY. CANADA GREATER TORONTO CERAMIC CENTER, 167 Lake Shore Rd., Toronto 14, Canada COLORADO LAKEWOOD POTTERY, 6955 W. Colfax, Lake- ATTENTION: DEALERS, STUDI so HOOLS I wood, Colorado CONNECTICUT See one of these RE-WARD Distribi~s for SYBIL GARVIN CERAMICS, 77 Main St., Port- quality products and land, Conn. servicI THE POTTER'S WHEEL, Post Road, Westport, Conn. ~mBAMA WASHINGTON, D. C. CERAMICS by OL~1828 Pinson St., Birming- McNOR'S CERAMIC STUDIO, 5113 Georgia Ave., ham, A a N.W., Washington, D.C. CERAMIC ART TRF,~IlRE HOUSE, 3658 S Perry DELAWARE .... • .... St., Montgomery, ~j~. CLAY DEN, 213 Fenwick Ave., Wilmington, -:~'~SKA Delaware THE MUD NESTi~]/~2 Lacey St., Fairbanks, FLORIDA JADOL ARTS & CRAFTS, 8965 Biscayne Blvd., Alaska ~NSAS Miami, Fla. ALLISON CERAI~rruDIO, 20 Arcade Bldg., GEORGIA Little Rock, Ark.UlWU PATRICIA TACKABERY, 3041 Boiling Way N. E., CALIFORNIA Atlanta, Ga. THE SHED, 1000 Santa Clara Ave., Alameda, IDAHO Calif. HOUSE OF WHITES, 5702 Fairview, Boise, Idaho POTTERY MILL, 1035 D St., Arcata, Calif. ILLINOIS STEWART'S of CALIFORNIA 7140 Firestone ILLINI CERAMIC SERVICE, INC., 439 N. -

A Study of Music As an Integral Part

A Study of Music as an Integral Part of the Spoken Drama in the American Professional Theatre: 1930-1955 By MAY ELIZABETH BURTON A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA August, 1956 PREFACE This is a study of why and how music is integrated with spoken drama in the contemporary American professional theatre. Very little has been written on the subject, so that knowledge of actual practices is limited to those people who are closely associated with commercial theatre-- composers, producers, playwrights, and musicians. There- fore, a summation and analysis of these practices will contribute to the existing body of knowledge about the contemporary American theatre. It is important that a study of the 1930-1955 period be made while it is still contemporary, since analysis at a later date would be hampered by a scarcity of detailed production records and the tendency not to copyright and publish theatre scores. Consequently, any accurate data about the status of music in our theatre must be gathered and re- corded while the people responsible for music integration are available for reference and correspondence. Historically, the period from 1930 to 1^55 is important because it has been marked by numerous fluc- tuations both in society and in the theatre. There are evidences of the theatre's ability to serve as a barometer of social and economic conditions. A comprehension of the ii degree and manner in which music has been a part of the theatre not only will provide a better understanding of the relationship between our specific theatre idiom and society, but suggests the degree to which it differs from that fostered by previous theatre cultures. -

GRMN 451.01: 20Th Century German Literature to 1945

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Syllabi Course Syllabi Spring 2-1-2019 GRMN 451.01: 20th Century German Literature to 1945 Hiltrudis Arens University of Montana - Missoula, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Arens, Hiltrudis, "GRMN 451.01: 20th Century German Literature to 1945" (2019). Syllabi. 10326. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi/10326 This Syllabus is brought to you for free and open access by the Course Syllabi at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syllabi by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Twentieth Century German Literature to 1945 GRMN 451 MWF 2:00-2:50pm Spring 2019 Contact Professor: Dr. Hiltrud Arens Office: LA 441 Office hours: Mon/Wed: 11:00-11:50 Uhr; 15:00-15:50:00 Uhr; or/and by appointment Telefon: 243-5634 (office) Email: [email protected] Language of instruction is German Learning Goals: 1) To give an introduction and a survey of turn of the century German-language literary works (also in translation available) up to 1945. 2) To examine a variety of genres, including novel, novella, short story, essay, letter, poetry, drama, and film; and to connect those to other medial forms like painting, graphic arts, music, and photography, as well as to other societal/scientific developments, such as psycho-analysis. 3) To obtain formal knowledge through studying the texts (primary and secondary texts) in terms of language usage, style, and structure. -

ILLUMINATING FEMALE IDENTITY THROUGH IRISH DRAMA Amy R

STRANGER IN THE ROOM: ILLUMINATING FEMALE IDENTITY THROUGH IRISH DRAMA Amy R. Johnson Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of English Indiana University June 2007 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My sincerest thanks are extended to my committee members for their time and feedback during this process. An added note of gratitude is extended to Dr. Jon Eller for helping to make this an educational and thoroughly enjoyable learning experience. Special appreciation goes to Dr. Mary Trotter for introducing me to many of the contemporary Irish dramatists discussed in this thesis and for her experience and expertise in this subject matter. Thanks to my fellow graduate students: Miriam Barr, Nancee Reeves and Johanna Resler for always being on my side and sharing my passion for books and words. Most importantly, thanks to Conan Doherty for always supporting me and for being the steadying voice in getting me here in spite of the hurdles. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter One, A Brief History ..............................................................................................1 Chapter Two, Dancing at Lughnasa..................................................................................23 Chapter Three, Ourselves Alone ........................................................................................40 Chapter Four, The Mai.......................................................................................................56 Chapter -

1 Pedestrian Performance

Pedestrian Performance: A Mapped Journey Volume 1 of 1 Submitted by Kristofor James Darby to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Drama In December 2012 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis could not have materialised without the unwavering support of a number of people who have all assisted me in my writing. First and foremost is my supervisor, Stephen Hodge, who gave me the freedom to make my own way through my research, whilst making sure that I did not wander too far off the beaten track. Both he and Dr Jane Milling have proven a perfect partnership in helping me ascertain points of correlation between the landscapes of theatre and performance studies. Within the Drama Department at the University of Exeter I must thank Dr Sarah Goldingay for helping me in drafting my initial proposal three years ago; Dr Cathy Turner for providing extra details concerning Wrights & Sites; Phil Smith for the mythogeographic walks; Dr Piotr Woycicki for introducing me to mirror neurons and Professor Graham Ley for convincing me to do a PhD in the first place. I must also thank my fellow PhD students for their support: Solomon Lennox, Erin Walcon, Ilaria Pinna, Richard Feltham, Aqeel Abdulla and Jens Peters. -

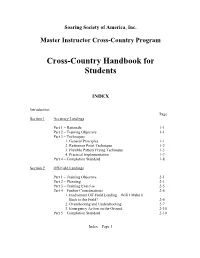

Cross-Country Handbook for Students

Soaring Society of America, Inc. Master Instructor Cross-Country Program Cross-Country Handbook for Students INDEX Introduction Page Section 1 Accuracy Landings Part 1 – Rationale 1-1 Part 2 – Training Objective 1-1 Part 3 – Techniques 1. General Principles 1-1 2. Reference Point Technique 1-2 3. Flexible Pattern Flying Technique 1-3 4. Practical Implementation 1-7 Part 4 – Completion Standard 1-8 Section 2 Off-Field Landings Part 1 – Training Objective 2-1 Part 2 – Planning 2-1 Part 3 – Training Exercise 2-5 Part 4 – Further Considerations 2-6 1. Inadvertent Off-Field Landing – Will I Make It Back to the Field? 2-6 2. Overshooting and Undershooting 2-7 3. Emergency Action on the Ground 2-10 Part 5 – Completion Standard 2-10 Index – Page 1 Section 3 Thermal Acquisition and Centering Part 1 – Training Objective 3-1 Part 2 – Suggested Text 3-1 Part 3 – Minimum Equipment 3-1 Part 4 – Safety 3-1 Part 5 – Practical Considerations 3-2 Part 6 – Training Exercise and Completion Standard 3-4 Section 4 Speed-to-Fly Part 1 – Training Objective 4-1 Part 2 – Suggested Text 4-1 Part 3 – Practical Considerations 4-1 Part 4 – Training Exercise and Completion Standard 4-3 Section 5 Map Reading and Navigation Part 1 – Training Objective 5-1 Part 2 – Training Exercise 5-1 Part 3 – Training Specifics 5-2 Part 4 – Completion Standard 5-4 Section 6 Cross-Country Techniques Part 1 – Training Objective 6-1 Part 2 – Exercise Prerequisites 6-1 Part 3 – Training Exercise 6-2 Part 4 – Training Specifics 1. -

Handbook AS-503, June 17, 2010

Contents How To Use This Handbook General Numbering System Reference Symbols Acronyms and Abbreviations Introduction 0-1 Policy Statement 0-2 Overview 0-3 Facility Types & Programs 0-4 Deviation Policy 0-5 Retail Design Review Policy 0-6 Directory Structure 0-7 USPS Reference Documents Appendices Appendix A Feedback Form Appendix B Deviation Request Form Appendix C Headquarters Design Review Form Module 1: General Criteria Chapter 1 Civil Chapter 2 Architectural Chapter 3 Structural Chapter 4 Mechanical Chapter 5 Electrical Standard Design Criteria Contents 1 Handbook AS-503, June 17, 2010 Module 2: Specific Criteria 2A Mail Processing Facilities Note that the criteria related to the facility type known as Mail Processing Facilities has been extracted and compiled in a separate folder named “MPF” (Mail Processing Facilities) in the Building Design Standards. 2B Medium Standard Building Designs (MSBD) Chapter 1 Civil (Not used, refer to Module 1, Chapter 1) Chapter 2 Architectural Chapter 3 Structural (Not used, refer to Module 1, Chapter 3) Chapter 4 Mechanical Chapter 5 Electrical 2C Small Standard Building Designs (SSBD) Chapter 1 Civil (Not used, refer to Module 1, Chapter 1) Chapter 2 Architectural Chapter 3 Structural (Not used, refer to Module 1, Chapter 3) Chapter 4 Mechanical (Not used, refer to Module 1, Chapter 4) Chapter 5 Electrical Standard Design Criteria Contents 2 Handbook AS-503, June 17, 2010 Module 3: Special Facility Types 3A Vehicle Maintenance Facilities (VMF) [See new MPF folder] 3B Modular Post Offices 3C Storage -

From Jantar-Mantar to Kavalur

Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers of India: RN.70269/98 ISSN: 0972-169X Monthly Newsletter of Vigyan Prasar December 15, 1999 Vol. 2 No.3 VP News Inside SCIENCE VIDEOS FROM VIGYAN PRASAR Coverage of science in Indian mass media, especially television, has been very poor. One reason, often heard in media circles, is the absence of a Editorial mechanism to cover stories of latest R&D developments from the science and technology institutions in the country. To bridge the gap between Mass media and R&D institutions, Vigyan Prasar has recently launched a science video Prasanta Chandra feature service on experimental basis. Mahalanobis Six feature stories have been produced last month. Three features on National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources and three on latest developments from the National Physical Laboratory, New Delhi. The feature stories cover From Jantar-Mantar the profile of the largest gene bank in the world - the NBPGR, various Ex-situ techniques to conserve seeds and a report on the plant quarantine division. to Kavalur The stories from NPL cover the 'Teleclock' service to transmit Time Data digitally through a telephone line, the SODAR - Sound Detection and flanging technique for air pollution management and the piezoelectric Accelerometer The Story of Wool PL-810 to measure vibrations. R&D organizations may write to us for covering interesting Research and Development works happening in their laboratories. Delhi's Water and Solid Waste Management: Emerging Scenario Vigyan Prasar has launched a series on India's Environmental Hotspots. The latest publication in this series is on Delhi's water and waste management scenario. -

Kurt Weill Foundation

Introduction and Notes by David Drew Whether you care to mention Weill in the same breath prominently among the modern poets in a family library it is to have any kind of raison d'etre. The thoroughly as Hindemith or as Hollander, as Copland or as Cole where the works of Goethe and Heine, of Johann un-topical representation of our times which would result Porter; whether you see him as an outstanding German Gottfried von Herder and Moses Mendelssohn, had pride from such a change of direction must be supported by composer who somehow lost his voice when he settled of place, and where, no doubt, one could have found a strong conviction, whether it uses an earlier epoch in America, or as an outstanding Broadway composer some of the writings of Eduard Bernstein , if not of (the to mirror aspects of present-day life or whether it finds who somehow contrived to write a hit-show called " The young?) Marx, and perhaps even a crumpled copy of a unique, definitive and timeless form for present-day Threepenny Opera" during his otherwise obscure and the Erfurt Programme of 1891 . phenomena. The absence of inner and outer complica probably misspent Berlin youth ; whether you disagree Unlike Brecht, Weill never needed to repudiate his early tions (in the material and in the means of expression) with both these views and either find evidence of a strik- backg round in order to define his artistic functions and is in keeping with the more naive disposition of the ingly original mind at all stages in his career (but at some objectives. -

Publication 28 Contents

Contents 1 Introduction. 1 11 Background . 1 111 Purpose . 1 112 Scope . 1 113 Additional Benefits . 1 12 Overview . 2 121 Address and List Maintenance . 2 122 List Correction. 2 123 Updates. 2 124 Address Output . 3 125 Deliverability . 3 13 Address Information Systems Products and Services . 3 2 Postal Addressing Standards . 5 21 General . 5 211 Standardized Delivery Address Line and Last Line. 5 212 Format . 5 213 Secondary Address Unit Designators . 6 214 Attention Line . 7 215 Dual Addresses . 7 22 Last Line of the Address. 8 221 City Names . 8 222 Punctuation . 8 223 Spelling of City Names . 8 224 Format . 9 225 Military Addresses. 9 226 Preprinted Delivery Point Barcodes . 9 23 Delivery Address Line . 10 231 Components . 10 232 Street Name . 10 233 Directionals . 11 234 Suffixes . 13 235 Numeric Street Names . 13 236 Corner Addresses . 14 237 Highways. 14 238 Military Addresses. 14 239 Department of State Addresses . 15 June 2020 i Postal Addressing Standards 24 Rural Route Addresses. 15 241 Format . 15 242 Leading Zero . 16 243 Hyphens . 16 244 Designations RFD and RD . 16 245 Additional Designations . 16 246 ZIP+4. 16 25 Highway Contract Route Addresses . 17 251 Format . 17 252 Leading Zero . 17 253 Hyphens . 17 254 Star Route Designations . 17 255 Additional Designations . 18 256 ZIP+4. 18 26 General Delivery Addresses . 18 261 Format . 18 262 ZIP Code or ZIP+4 . 18 27 United States Postal Service Addresses . 19 271 Format . 19 272 ZIP Code or ZIP+4 . 19 28 Post Office Box Addresses. 19 281 Format . 19 282 Leading Zero . -

ISSN 0142-064X the Charge of Blasphemy in Mark 14.64

[JSNT 26.4 (2004) 379-401] ISSN 0142-064X The Charge of Blasphemy in Mark 14.64 Adela Yarbro Collins Yale University Divinity School 409 Prospect Street, New Haven, CT 06511, USA [email protected] Abstract The teaching of m. Sanh. 7.5, that the ‘blasphemer’ is not culpable unless he pronounces the Name itself, is attested by Josephus and the Community Rule from Qumran. The Markan Jesus, however, does not pronounce the divine name. Philo provides evidence for a broader understanding of blas- phemy, namely, claims to be divine or to possess divine power. The relevant passages are analogous to the Markan Jesus’ claims that he would be en- throned at the right hand of God and that he would ‘come with the clouds of heaven’. Both claims imply divine status, authority and power. The chief priests, as Sadducees, probably subscribed to a definition of blasphemy like that of Philo. Like other Jews of the time, they advocated the death penalty for blasphemy, but were more likely to carry it out. Mark did not wish to deny that Jesus blasphemed from the point of view of the chief priests. The narrative is ironic in the sense that what is blasphemy from the point of view of the council is true from the perspective of the implied audience. A great deal of the scholarship on the trial of Jesus before the high priest and the council of Judea in Mark has focused on the question of the his- torical reliability of the account.1 One of the issues involved in such studies is the question of responsibility for the death of Jesus, a sensitive issue for Jewish–Christian relations, especially since the Nazis’ attempt to exterminate the Jews and the subsequent examination by Christians of their tradition, in which the Christian roots of anti-Semitism have been 1.