Issue Manipulation by the Burger Court: Saving the Community from Itself Suzanna Sherry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technology Fa Ct Or

Art.Id Artist Title Units Media Price Origin Label Genre Release A40355 A & P Live In Munchen + Cd 2 Dvd € 24 Nld Plabo Pun 2/03/2006 A26833 A Cor Do Som Mudanca De Estacao 1 Dvd € 34 Imp Sony Mpb 13/12/2005 172081 A Perfect Circle Lost In the Bermuda Trian 1 Dvd € 16 Nld Virgi Roc 29/04/2004 204861 Aaliyah So Much More Than a Woman 1 Dvd € 19 Eu Ch.Dr Doc 17/05/2004 A81434 Aaron, Lee Live -13tr- 1 Dvd € 24 Usa Unidi Roc 21/12/2004 A81435 Aaron, Lee Video Collection -10tr- 1 Dvd € 22 Usa Unidi Roc 21/12/2004 A81128 Abba Abba 16 Hits 1 Dvd € 20 Nld Univ Pop 22/06/2006 566802 Abba Abba the Movie 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 29/09/2005 895213 Abba Definitive Collection 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 22/08/2002 824108 Abba Gold 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 21/08/2003 368245 Abba In Concert 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 25/03/2004 086478 Abba Last Video 1 Dvd € 16 Nld Univ Pop 15/07/2004 046821 Abba Movie -Ltd/2dvd- 2 Dvd € 29 Nld Polar Pop 22/09/2005 A64623 Abba Music Box Biographical Co 1 Dvd € 18 Nld Phd Doc 10/07/2006 A67742 Abba Music In Review + Book 2 Dvd € 39 Imp Crl Doc 9/12/2005 617740 Abba Super Troupers 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 14/10/2004 995307 Abbado, Claudio Claudio Abbado, Hearing T 1 Dvd € 34 Nld Tdk Cls 29/03/2005 818024 Abbado, Claudio Dances & Gypsy Tunes 1 Dvd € 34 Nld Artha Cls 12/12/2001 876583 Abbado, Claudio In Rehearsal 1 Dvd € 34 Nld Artha Cls 23/06/2002 903184 Abbado, Claudio Silence That Follows the 1 Dvd € 34 Nld Artha Cls 5/09/2002 A92385 Abbott & Costello Collection 28 Dvd € 163 Eu Univ Com 28/08/2006 470708 Abc 20th Century Masters -

Building Construction

EIA GUIDANCE MANUAL - Building, Construction, Townships and Area Development Projects Ministry of Environment & Forests GOVERNMENT OF INDIA, NEW DELHI Environmental Impact Assessment Guidance Manual for BUILDING, CONSTRUCTION, TOWNSHIPS and AREA DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS Prepared by Administrative Staff College of India Bellavista, Khairatabad, Hyderabad February 2010 Environmental Impact Assessment Guidance Manual for Building, Construction, Townships and Area Development Siripurapu K. Rao M.A. (Cantab), Ph.D. (Cantab) DIRECTOR GENERAL Leadership through Learning Acknowledgements Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is a planning tool generally accepted as an integral component of sound decision-making. EIA is to give the environment its due place in the decision-making process by clearly evaluating the environmental consequences of the proposed activity before action is taken. Early identification and characterization of critical environmental impacts allow the public and the government to form a view about the environmental acceptability of a proposed developmental project and what conditions should apply to mitigate or reduce those risks and impacts. Environmental Clearance (EC) for certain developmental projects has been made mandatory by the Ministry of Environment & Forests through its Notification issued on 27.01.1994 under the provisions of Environment (Protection) Act, 1986. Keeping in view a decade of experience in the Environmental Clearance process and the demands from various stakeholders, the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) issued revised Notification on EC process in September 2006 and amended it in December 2009.It was considered necessary by MoEF to make available EIA guidance manuals for each of the development sector. Accordingly, at the instance of the MoEF, the Administrative Staff College of India, with the assistance of experts, undertook the preparation of sector specific Terms of Reference (TOR) and specific guidance manual for Building, Construction, townships and area development projects. -

Nr Kat EAN Code Artist Title Nośnik Liczba Nośników Data Premiery Repertoire 19075816441 190758164410 '77 Bright Gloom Vinyl

nr kat EAN code artist title nośnik liczba nośników data premiery repertoire 19075816441 190758164410 '77 Bright Gloom Vinyl Longplay 33 1/3 2 2018-04-27 HEAVYMETAL/HARDROCK 19075816432 190758164328 '77 Bright Gloom CD Longplay 1 2018-04-27 HEAVYMETAL/HARDROCK 9985848 5051099858480 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us CD Longplay 1 2015-10-30 HEAVYMETAL/HARDROCK 88697636262 886976362621 *NSYNC The Collection CD Longplay 1 2010-02-01 POP 88875025882 888750258823 *NSYNC The Essential *NSYNC CD Longplay 2 2014-11-11 POP 19075906532 190759065327 00 Fleming, John & Aly & Fila Future Sound of Egypt 550 CD Longplay 2 2018-11-09 DISCO/DANCE 88875143462 888751434622 12 Cellisten der Berliner Philharmoniker, Die Hora Cero CD Longplay 1 2016-06-10 CLASSICAL 88697919802 886979198029 2CELLOS 2CELLOS CD Longplay 1 2011-07-04 CLASSICAL 88843087812 888430878129 2CELLOS Celloverse CD Longplay 1 2015-01-27 CLASSICAL 88875052342 888750523426 2CELLOS Celloverse CD Longplay 2 2015-01-27 CLASSICAL 88725409442 887254094425 2CELLOS In2ition CD Longplay 1 2013-01-08 CLASSICAL 19075869722 190758697222 2CELLOS Let There Be Cello CD Longplay 1 2018-10-19 CLASSICAL 88883745419 888837454193 2CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb DVD Video Longplay 1 2013-11-05 CLASSICAL 88985349122 889853491223 2CELLOS Score CD Longplay 1 2017-03-17 CLASSICAL 88985461102 889854611026 2CELLOS Score (Deluxe Edition) CD Longplay 2 2017-08-25 CLASSICAL 19075818232 190758182322 4 Times Baroque Caught in Italian Virtuosity CD Longplay 1 2018-03-09 CLASSICAL 88985330932 889853309320 9ELECTRIC The Damaged Ones -

Lemmy Kilmister Was Born in Stoke-On-Trent

Lemmy Kilmister was born in Stoke-on-Trent. Having been a member of the Rocking Vicars, Opal Butterflies and Hawkwind, Lemmy formed his own band, Motörhead. The band recently celebrated their twenty-fifth anniversary in the business. Lemmy currently lives in Los Angeles, just a short walk away from the Rainbow, the oldest rock ’n’ roll bar in Hollywood. Since 1987, Janiss Garza has been writing about very loud rock and alternative music. From 1989 to1996 she was senior editor at RIP, at the time the World’s premier hard music magazine. She has also written for Los Angeles Times, Entertainment Weekly, and New York Times, Los Angeles. ‘From heaving burning caravans into lakes at 1970s Finnish festivals to passing out in Stafford after three consecutive blowjobs, the Motörhead man proves a mean raconteur as he gabbles through his addled heavy metal career résumé’ Guardian ‘As a rock autobiography, White Line Fever is a keeper’ Big Issue ‘White Line Fever really is the ultimate rock & roll autobiography . Turn it up to 11 and read on!’ Skin Deep Magazine First published in Great Britain by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd, 2002 This edition first published by Pocket, 2003 An imprint of Simon & Schuster UK Ltd A Viacom Company Copyright © Ian Kilmister and Janiss Garza, 2002 This book is copyright under the Berne Convention. No reproduction without permission. All rights reserved. The right of Ian Kilmister to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. Simon & Schuster UK Ltd Africa House 64-78 Kingsway London WC2B 6AH www.simonsays.co.uk Simon & Schuster Australia Sydney A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from British Library Paperback ISBN 0-671-03331-X eBook ISBN 978-1-47111-271-3 Typeset by M Rules Printed and bound in Great Britain by Cox & W yman Ltd, Reading, Berks PICTURE CREDITS The publishers have used their best endeavours to contact all copyright holders. -

Sello Formato Banda Titulo Precio Tarj Efectivo Del

SELLO FORMATO BANDA TITULO PRECIO TARJ EFECTIVO DEL IMAGINARIOCD 1349 BEYOND THE APOCALYPSE 1150 1035 DEL IMAGINARIOCD 1349 DEMONOIR 1150 1035 DEL IMAGINARIOCD 1349 LIBERATION 1150 1035 ICARUS CD 3 INCHES OF BLOOD LONG LIVE HEAVY METAL 900 810 ACQUA CD 34 PUÑALADAS ASTIYA 700 630 GOBI CD 5 ENCANTANDO 5 ENCANTANDO 400 360 GOBI CD 5 ENCANTANDO ENCANTADOS DE CANTARLES 520 468 UNIVERSAL CD 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER CALM 900 810 YA! MUSICA CD 8 8 520 468 YA! MUSICA DVD 8 MUJERES (UN FILM DE FRANCOIS OZON) 300 270 WARNER CD A HA-THE SINGLES: 1984 - 2004 1150 1035 ICARUS CD A PERFECT DAY A PERFECT DAY 900 810 YA! MUSICA DVD A.BANDERAS/M.RYAN EL NUEVO NOVIO DE MI MAMA 300 270 YA! MUSICA DVD A.GADES/L.DEL SOL/P. DE LUCIACARMEN 300 270 SONY MUSIC CD+DVD A.N.I.M.A.L VIVO RED HOUSE (CD + DVD) 1200 1080 UNIVERSAL CD ABBA ABBA GOLD 800 720 UNIVERSAL CD ABBA ORO 380 342 UNIVERSAL 2CDS ABBA THE DEFINITIVE COLLECTION 1150 1035 MAGENTA CD ABBAMANIA LA MUSICA ABBA 250 225 DEL IMAGINARIOCD ABBATH ABBATH 1150 1035 PRO COM DVD ABBOTT & COSTELO UNA AVENTURA EN AFRICA 350 315 AFC CD ABEL IVROUD CAMARADAS DEL CRIMEN 320 288 AFC CD ABEL IVROUD CARTA A UN HERMANO PRESO 320 288 AFC CD ABEL IVROUD CHAPARRONES VOL.14 320 288 AFC CD ABEL IVROUD CUESTION DE TODOS 320 288 AFC CD ABEL IVROUD ENTRE HACIENDA Y PASTIZALES 320 288 AFC CD ABEL IVROUD LEYENDAS 3 320 288 SONY MUSIC CD ABEL PINTOS 11 1150 1035 SONY MUSIC CD ABEL PINTOS ABEL 900 810 SONY MUSIC CD ABEL PINTOS COSAS DEL CORAZON 750 675 SONY MUSIC 2CDS ABEL PINTOS LA FAMILIA FESTEJA FUERTE 1400 1260 SONY MUSIC CD COMBO -

Katalog Sony Music 16.04.2020.Xlsx

nr kat EAN code artist title nośnik liczba nośników data premiery repertoire 19075816432190758164328'77 Bright Gloom CD Longplay 1 2018-04-27 HEAVYMETAL/HARDROCK 19075816441190758164410'77 Bright Gloom Vinyl Longplay 33 1/3 2 2018-04-27 HEAVYMETAL/HARDROCK 88697636262886976362621*NSYNC The Collection CD Longplay 1 2010-02-01 POP 88875025882888750258823*NSYNC The Essential *NSYNC CD Longplay 2 2014-11-11 POP 1907590653219075906532700 Fleming, John & Aly & Fila Future Sound of Egypt 550 CD Longplay 2 2018-11-09 DISCO/DANCE 8887514346288875143462212 Cellisten der Berliner Philharmoniker, Die Hora Cero CD Longplay 1 2016-06-10 CLASSICAL 1907592212219075922122821 Savage i am > i was CD Longplay 1 2019-01-11 RAP/HIPHOP 1907592212119075922121121 Savage i am > i was Vinyl Longplay 33 1/3 2 2019-03-01 RAP/HIPHOP 886979198028869791980292CELLOS 2CELLOS CD Longplay 1 2011-07-04 CLASSICAL 888430878128884308781292CELLOS Celloverse CD Longplay 1 2015-01-27 CLASSICAL 888750523428887505234262CELLOS Celloverse CD Longplay 2 2015-01-27 CLASSICAL 887254094428872540944252CELLOS In2ition CD Longplay 1 2013-01-08 CLASSICAL 190758697221907586972222CELLOS Let There Be Cello CD Longplay 1 2018-10-19 CLASSICAL 888837454198888374541932CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb DVD Video Longplay 1 2013-11-05 CLASSICAL 889853491228898534912232CELLOS Score CD Longplay 1 2017-03-17 CLASSICAL 889854611028898546110262CELLOS Score (Deluxe Edition) CD Longplay 2 2017-08-25 CLASSICAL 190759538011907595380123TEETH METAWAR Vinyl Longplay 33 1/3 2 2019-07-05 HEAVYMETAL/HARDROCK 190759537921907595379233TEETH -

Republican Journal

The Republican Journal. VOLUME 56. BELFAST, MAINE, THURSDAY, JULY 24, 1884. NUMBER 30. FARM. CARDEN AND HOUSEHOLD. times to wash as to and Yes ana No. at rut A to President Eliot. more, pick it, the widder's, an’ wood fer her the But jest then one of oar neighbor Reply Literary News and Notes. Letter from Colorado. RKITRLICAX are .JOURNAL. '.lien the berries not worth half price IIY JOSEPHINE rOLL VRD. hull Then at night, the wirnmen- fam'lies come been to the day. ’long. They’d LETTER FROM HON. EDWARD MCPHERSON. NOTES FKOM A WALDO I’Ot'NTV MAN IN THE Tor rhi-, brief faeis to to market or to department suggestions, send keep for home are two so folks would all come in with baskets o' wood-euttin’ an’ was on their The Midsummer Century will con- There little words, small too, way To The Editor of the Boston Journal : Holiday W EST. 1 I H! I ->M KI h V KK Y rillUMi.U MORNING BY TH K ! and experiem are -olieitetl from housekeep- use. These differences may make all the They seem of no account at all. good an' they’d have a an' home. President Eliot ami tain “A dance at British Wild Flowers" by er-. farmer- and gardener-. Address Agri- things, party makes in his anti-Blaine [Correspondence of the Journal.] difference between a As over careless fall: t paying crop, and lips they a real time of it. Wo Lif an’ he a-bed of the 2‘Jlii tilt., an attack John and Alfred Parsons the artist. -

Diabolical Enticement of Blood... CD 6.000 $ AC/DC

ITEM PRECIO 9TH ENTITY - Diabolical Enticement of Blood... CD $ 6.000 AC/DC - Llavero logo banda $ 2.900 AC/DC - Llavero tapa botella $ 3.900 ACCEPT - Blind Rage CD $ 11.900 ACCEPT - The Rise of Chaos LP $ 25.900 AD NOCTUM PROJECT - The Last March CD $ 6.900 ADA CREW - Coming to Town CD $ 5.900 ADVERSARIAL - All Idols Fall Before de Hammer CD $ 6.900 AFTER DUSK - The Character Of Physical Law CD $ 6.900 AGNOSTIC FRONT - The American Dream Died CD $ 11.900 AGNOSTIC FRONT - Warriors / My life my way CD $ 15.900 AGORAPHOBIC NOSEBLEED / DESPISE YOU - And on... CD $ 11.900 AKBAL - Mirando al Cielo CD $ 6.900 AKERCOCKE - Words That Go Unspoken Deeds... CD+DVD $ 13.900 AKRAMEN - Bajo Control CD $ 6.900 ALL KINGS FALL - Drink To the Lost CD DIGI $ 6.900 ALL SHALL PERISH - Awake the Dreamers CD+DVD SLIP $ 9.900 AMETHYST - Time Of Slaughters CD $ 6.900 AMON AMARTH - Jomsviking CD $ 11.900 AMORPHIS - Forging The Land ... 2CD+2DVD $ 19.900 AMORPHIS - Magic & Mayhem CD $ 11.900 AMORPHIS - My Kantele CD DIGI $ 10.900 AMORPHIS - Tuonela CD $ 11.900 AMORPHIS - Under The Red Cloud CD $ 12.900 ANARCHUS - Still Alive (.And Still Too Drunk) CD $ 6.900 ANATHEMA - A Sort Of Homecoming 2CD+DVD $ 17.900 ANATHEMA - A Sort Of Homecoming BOXSET $ 24.900 ANATHEMA - Distant Satellites 2CD $ 21.900 ANATHEMA - The Optimist 2LP $ 27.900 ANATHEMA - The Optimist CD DIGI $ 13.900 ANATHEMA - The Optimist CD+DVD DIGIBOOK $ 18.900 ANATHEMA - The Optimist EARBOOK $ 59.900 ANATHEMA - Universal CD+DVD DIGIBOOK $ 16.900 ANIMA INMORTALIS - More Than Just Flesh...CD DIGI $ 7.900 -

Her Şey Bir Merhaba Ile Başlar

Her Şey Bir Merhaba ile Başlar Jeannette Okur ii CC BY-SA 2021 Jeannette Okur Publishing & License Information 2021, Center for Open Educational Resources and Language Learning (COERLL) Produced by Jeannette Okur, Assistant Professor of Instruction in Middle Eastern Studies and Turkish Program Coordinator, The University of Texas at Austin This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution -ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042. First Edition ISBN: 978-1-937963-21-7 Library of Congress number: 2020924521 Manufactured in the United States of America. Front cover art by Craig Kotfas. Photos used on front cover: Pixabay License, https://pixabay.com/photos/cat-cats-ephesus-turkey-fur-5195423/ CC BY 2.0, “Neighborhood” by Richard Ha, https://www.flickr.com/photos/richardha101/22291458340/in/ album-72157659562336395/ CC by 2.0, “Young Turkish Women Pose with Ataturk Memorial - Chunuk Bair - Gallipoli Peninsula - Dardanelles - Turkey – 02” by Adam Jones, https://www.flickr.com/photos/adam_jones/5734776178/in/ album-72157626719749130/ CC0 (public domain), https://pixnio.com/objects/colorful-turkish-bowls CC BY 2.0, “Woman and Young Girl - Old City - Diyarbakir – Turkey” by Adam Jones, https://www.flickr.com/photos/adam_jones/5780934772/in/album-72157626719749130/ CC BY 2.0. “Turkish Visitors on Akdamar Island - Lake Van - Turkey – 01” by Adam Jones, https://www.flickr.com/photos/adam_jones/5796817924/in/album-72157626719749130/ -

Art.Id Artist Title Unitsmedia Price € Orderinfo Origin Statuscode Label

Art.Id Artist Title Units Media Price € Orderinfo Origin StatuscodeLabel Prefix Suffix Genre Release Eancode F30377 Aaliyah Losing Aaliyah Dvd 11,30 Nld Mvd D 7670 Spw 01.04.2009 0655690767063 G08688 Abba Abba In Japan Dvd 7,40 Nld Polar 06025 2710231 Pop 22.10.2009 0602527102313 G08687 Abba Abba In Japan -Deluxe- 2 Dvd 17,40 Nld Polar 06025 2710230 Pop 22.10.2009 0602527102306 895213 Abba Definitive Collection Dvd 7,40 Nld Univ 00440 0174459 Pop 22.08.2002 0044001744594 368245 Abba In Concert Dvd 14,20 Nld Univ 00440 0656469 Pop 25.03.2004 0044006564692 G00104 Abbado, Claudio Russian Night Dvd 8,99 Nld Dg 00440 0734530 Cls 08.10.2009 0044007345306 626922 Abercrombie, John Live At the Village Vangu Dvd 9,90 Nld Immo Imm 940055 Jaz 15.11.2007 8712177046331 G80433 Abercrombie, John Solos: the Jazz Sessions Dvd 10,50 Nld Mvd Mvdd 5010 Jaz 22.07.2010 0760137501091 A97490 Aborted Auricular Chronicles Live Dvd 14,30 Nld List Posdvd 090 Hm. 02.11.2006 3760053840905 F85910 Abrahams, Mick Black Night is Falling Dvd 15,85 Nld Dr.Ca Smadvd 215x Roc 20.07.2009 0636551521574 F98254 Ac/Dc Back In Black Dvd 5,90 Nld Immoc Imc 942001 Roc 24.09.2009 8712177056323 J27093 Ac/Dc Dirty Deeds 4 Dvd 19,99 Nld Abstr Absb 001 Hr. 15.11.2010 9780956603807 J02842 Ac/Dc Inside the Music 3 Dvd 11,50 Nld Anvil Anv 3577 Doc 15.07.2010 0823880035777 918128 Ac/Dc Live At Donington Dvd 13,50 Nld Sony 2022149 Hr. -

Metal Breath Č. 49

Metal Breath ’zine #49 (červen 2006) strana: 39 Distribuční katalog - DVD (DVD - domácí i zahraniční scéna) - pokračování ze strany 23 LED ZEPPELIN - The Song Remains The Same, Velká Británie, 576,- SCORPIONS - Acoustica, Německo, 900,- LED ZEPPELIN - The Song Remains The Same, Velká Británie, 696,- SEPULTURA - Chaos DVD, Brazílie, 696,- LENNON JOHN - Sweet Toronto, 624,- SEPULTURA - Live In Sao Paulo, 2 DVD, Brazílie, 900,- LIFE OF AGONY - River Runs Again Live 2003, USA, 900,- SIX FEET UNDER - Double Dead, 2 DVD, USA, 780,- LYNYRD SKYNYRD - Live, USA, 780,- SLAYER - War At The Warfield, USA, 900,- MADONNA - The Video Collection, USA, 576,- SLIPKNOT - Diaserpieces, 2 DVD, USA, 1020,- MALMSTEEN YNGWIE - Live!!, Švédsko, 900,- SODOM - Lords Ogf Depravity Part 1, 2 DVD, Německo, 984,- MALMSTEEN YNGWIE - Video Clips, japonská verze DVD, Švédsko, SOULFLY - The Song Remains Insane, USA, 900,- 780,- SPOCK'S BEARD - Don't Try This At Home, 2 DVD, USA, 1140,- MANOWAR - Hell On Earth - Part I, USA, 780,- STRANGLERS - Friday The Thirdteen, 744,- MANOWAR - Hell On Earth - Part III, 2 DVD, USA, 1140,- STRATOVARIUS - Infinite Visions, Finsko, 900,- MANOWAR - Hell On Earth - PART IV, 2 DVD + CD, USA, 1104,- SUM 41 - Introduction To Destruction, Kanada, 660,- MANOWAR - Warriors Of The World United, DVD + CD, USA, 696,- THERAPY? - Scopophobia, Velká Británie, 744,- MARDUK - Blackcrowned, Švédsko, 780,- TRANSATLANTIC - Live In Europe, 2 DVD, 1104,- MARILYN MANSON - Birth Of The Antichrist, USA, 900,- TRISTANIA - Midwinter Tears, DVD + CD, Norsko, 624,- MARILYN MANSON - Demystifying The Devil, USA, 900,- TYPE O NEGATIVE - After Dark, USA, 900,- MAYHEM - Live In Marseille 2000, 1140,- U.D.O. -

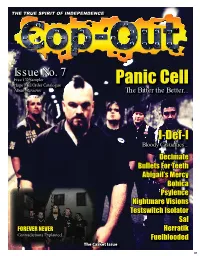

Cop out Magazine 07 – Web Version

TTHEHE TRUETRUE SPIRITSPIRIT OFOF INDEPENDENCEINDEPENDENCE IIssuessue No.No. 7 FFreeree CCDD SSamplerampler PPanicanic CCellell HHugeuge MMailail OOrderrder CCatalogueatalogue AAlbumlbum RReviewseviews TThehe BBitteritter tthehe BBetter...etter... II-Def-I-Def-I BBloodyloody CCasualties...asualties... DDecimateecimate BBulletsullets ForFor TeethTeeth AAbigail’sbigail’s MMercyercy BBohicaohica PPsylencesylence NNightmareightmare VVisionsisions TTestswitchestswitch IIsolatorsolator SSalal FFOREVEROREVER NNEVEREVER HHerratikerratik CContradictionsontradictions EExplained...xplained... FFuelbloodeduelblooded TThehe CCasketasket IssueIssue 01 02 CCOP-OUTOP-OUT #7#7 IIss bboughtought ttoo yyouou withwith thhee hhelpelp aandnd aassistences of the following people. Welcome To Cop-Out 07 sistence of the following people. HHelloello andand welcomewelcome toto anotheranother instalmentinstalment ofof Cop-Out,Cop-Out, thethe underfunded,underfunded, badlybadly writtenwritten andand cclobberedlobbered togethertogether catazinecatazine fromfrom thosethose jokersjokers atat CoproCopro Towers.Towers. SomeSome ofof youyou willwill bebe sur-sur- EEDITORDITOR JJoseose GGrifriffi n pprisedrised toto fi nnallyally havehave anotheranother oneone ofof thesethese fallfall onon youryour doordoor mat,mat, somesome ofof you,you, willwill bebe wonder-wonder- [email protected]@coproreords.co.uk iingng jjustust wwhathat tthehe hellhell thisthis is,is, butbut hopefullyhopefully allall ofof you,you, oror atat thethe veryvery leastleast mostmost ofof you,you,