The Behavior of the Horned Grebe in Spring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birds of Bharatpur – Check List

BIRDS OF BHARATPUR – CHECK LIST Family PHASIANIDAE: Pheasants, Partridges, Quail Check List BLACK FRANCOLIN GREY FRANCOLIN COMMON QUAIL RAIN QUAIL JUNGLE BUSH QUAIL YELLOW-LEGGED BUTTON QUAIL BARRED BUTTON QUAIL PAINTED SPURFOWL INDIAN PEAFOWL Family ANATIDAE: Ducks, Geese, Swans GREATER WHITE-FRONTED GOOSE GREYLAG GOOSE BAR-HEADED GOOSE LWSSER WHISTLING-DUCK RUDDY SHELDUCK COMMON SHELDUCK COMB DUCK COTTON PYGMY GOOSE MARBLED DUCK GADWALL FALCATED DUCK EURASIAN WIGEON MALLARD SPOT-BILLED DUCK COMMON TEAL GARGANEY NORTHERN PINTAIL NORTHERN SHOVELER RED-CRESTED POCHARD COMMON POCHARD FERRUGINOUS POCHARD TUFTED DUCK BAIKAL TEAL GREATER SCAUP BAER’S POCHARD Family PICIDAE: Woodpeckers EURASIAN WRYNECK BROWN-CAPPED PYGMY WOODPECKER YELLOW-CROWNED WOODPECKER BLACK-RUMPED FLAMBACK Family CAPITONIDAE: Barbets BROWN-HEADED BARBET COPPERSMITH BARBET Family UPUPIDAE: Hoopoes COMMON HOOPOE Family BUCEROTIDAE: Hornbills INDAIN GREY HORNBILL Family CORACIIDAE: Rollers or Blue Jays EUROPEAN ROLLER INDIAN ROLLER Family ALCEDINIDAE: Kingfisher COMMON KINGFISHER STORK-BILLED KINGFISHER WHITE-THROATED KINGFISHER BLACK-CAPPED KINGFISHER PIED KINGFISHER Family MEROPIDAE: Bee-eaters GREEN BEE-EATER BLUE-CHEEKED BEE-EATER BLUE-TAILED BEE-EATER Family CUCULIDAE: Cuckoos, Crow-pheasants PIED CUCKOO CHESTNUT-WINGED CUCKOO COMMON HAWK CUCKOO INDIAN CUCKOO EURASIAN CUCKOO GREY-BELLIED CUCKOO PLAINTIVE CUCKOO DRONGO CUCKOO ASIAN KOEL SIRKEER MALKOHA GREATER COUCAL LESSER COUCAL Family PSITTACIDAS: Parrots ROSE-RINGED PARAKEET PLUM-HEADED PARKEET Family APODIDAE: -

The Penguin-Dance of the Great Crested Grebe

NOTES The Penguin-dance of the Great Crested Grebe.—The Editors have asked me to comment briefly on the remarkable photograph of the Penguin-dance of the Great Crested Grebe (Podiceps cristatus) published in this issue (plate 48). Comparatively few observers have been fortunate enough to "witness this elaborate form of courtship which has rarely been photographed, being the least often performed of this species' four main ceremonies (first described fully and named by J. S. Huxley in Proc. Zool. Soc. London, 1914, pp. 491-562). As in the far more common Head- shaking, the male and female grebe play identical r61es in the Penguin-dance, whereas in the Discovery and the "Display" ceremonies the rdles are different though interchangeable. Penguin-dancing usually occurs in the vicinity of the nest-site, within the territory of the pair, and is almost invariably preceded and followed by a long bout of intense Head-shaking in which Habit-preening is absent. The two birds dive and, while submerged, collect a bill-full of ribbony water-weed. On emergence, they swim towards each other with their tippets fully spread and, when quite close, both rear up out of the water simultaneously. They then meet breast to breast with only the very end of the body in the water, feet splashing to keep up, as shown in the photograph. As they sway together thus for a few seconds, they waggle their heads, gradually dropping the weed. After the normal Head-shaking which follows, the pair sometimes swim to the nest-platform where soliciting and copulation may occur. -

Breeding of the Leach's Storm-Petrel Oceanodroma Leucorhoa at Santa Catalina Island, California

Carter et al.: Leach’s Storm-Petrel at Santa Catalina Island 83 BREEDING OF THE LEACH’S STORM-PETREL OCEANODROMA LEUCORHOA AT SANTA CATALINA ISLAND, CALIFORNIA HARRY R. CARTER1,3,4, TYLER M. DVORAK2 & DARRELL L. WHITWORTH1,3 1California Institute of Environmental Studies, 3408 Whaler Avenue, Davis, CA 95616, USA 2Catalina Island Conservancy, 125 Clarissa Avenue, Avalon, CA 90704, USA 3Humboldt State University, Department of Wildlife, 1 Harpst Street, Arcata, CA 95521, USA 4Current address: Carter Biological Consulting, 1015 Hampshire Road, Victoria, BC V8S 4S8, Canada ([email protected]) Received 4 November 2015, accepted 5 January 2016 Among the California Channel Islands (CCI) off southern California, Guadalupe Island, off central-west Baja California (Ainley 1980, the Ashy Storm-Petrel Oceanodroma homochroa (ASSP) is the Power & Ainley 1986, Ainley 2005, Pyle 2008, Howell et al. most numerous and widespread breeding storm-petrel; it is known 2009). Alternatively, these egg specimens may have been from to breed at San Miguel, Santa Cruz, Anacapa, Santa Barbara, and dark-rumped LESP, which are known to breed at the Coronado San Clemente islands (Hunt et al. 1979, 1980; Sowls et al. 1980; and San Benito islands, Baja California (Ainley 1980, Power & Carter et al. 1992, 2008; Harvey et al. 2016; Fig. 1B; Appendix 1, Ainley 1986). available on the website). Low numbers of Black Storm-Petrels O. melania (BLSP) also breed at Santa Barbara Island (Pitman Within this context, we asked the following questions: (1) Were the & Speich 1976; Hunt et al. 1979, 1980; Carter et al. 1992; 1903 egg records the first breeding records of LESP at Catalina and Appendix 1). -

Macroscopic Embryonic Development of Guinea Fowl Compared to Other Domestic Bird Species 2 Araújo Et Al

R. Bras. Zootec., 48:e20190056, 2019 https://doi.org/10.1590/rbz4820190056 Reproduction Full-length research article Macroscopic embryonic Brazilian Journal of Animal Science ISSN 1806-9290 www.rbz.org.br development of Guinea fowl compared to other domestic bird species Itallo Conrado Sousa de Araújo1* , Luana Rudrigues Lucas2, Juliana Pinto Machado3 , Mariana Alves Mesquita3 1 Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Escola de Veterinária, Departamento de Zootecnia, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brasil. 2 Faculdade de Ciências da Saúde de Unaí, Faculdade de Veterinária, Unaí, MG, Brasil. 3 Universidade Federal de Goiás, Programa de Pós-graduação em Zootecnia, Goiânia, GO, Brasil. *Corresponding author: ABSTRACT - Since few studies have addressed the embryonic development of [email protected] Guinea fowl (Numida meleagris), the objective of the present study was to evaluate Received: March 28, 2019 its embryonic development in the Cerrado region of Brazil and compare the results to Accepted: August 25, 2019 published descriptions of the embryonic development of other domestic bird species. How to cite: Araújo, I. C. S.; Lucas, L. R.; Machado, J. P. and Mesquita, M. A. 2019. The commercialized weight for Guinea fowl eggs used in the experiment was found to Macroscopic embryonic development of Guinea be 37.57 g, while egg fertility was 92%. Embryo growth rate (%) was higher on the fowl compared to other domestic bird species. sixth day of incubation relative to other days. The heart began beating on the third day Revista Brasileira de Zootecnia 48:e20190056. of development, while eye pigmentation and upper and lower limb buds appeared on https://doi.org/10.1590/rbz4820190056 the sixth day. -

Clapper Rail (Rallus Longirostris) Studies in Alabama Dan C

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aquila Digital Community Northeast Gulf Science Volume 2 Article 2 Number 1 Number 1 6-1978 Clapper Rail (Rallus longirostris) Studies in Alabama Dan C. Holliman Birmingham-Southern College DOI: 10.18785/negs.0201.02 Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/goms Recommended Citation Holliman, D. C. 1978. Clapper Rail (Rallus longirostris) Studies in Alabama. Northeast Gulf Science 2 (1). Retrieved from https://aquila.usm.edu/goms/vol2/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gulf of Mexico Science by an authorized editor of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Holliman: Clapper Rail (Rallus longirostris) Studies in Alabama Northeast Gulf Science Vol. 2, No.1, p. 24-34 June 1978 CLAPPER RAIL (Rallus longirostris) STUDIES IN ALABAMAl Dan C. Holliman Biology Department Birmingham-Southern College Birmingham, AL 35204 ABSTRACT: The habitat and distribution of the clapper rail Rallus longirostris saturatus in salt and brackish-mixed marshes of Alabama is described. A total of 4,490 hectares of habitat is mapped. Smaller units of vti'getation are characterized in selected study areas. A comparison of these plant communities and call, count data is shown for each locality. Concentrations of clapper rails generally occurrecj in those habitats with the higher percentage of Spartina alterniflora. A census techni que utilizing taped calls is described. Trapping procedures are given for drift fences and funnel traps. -

![LOONS and GREBES [ ] Common Loon [ ] Pied-Billed Grebe---X](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1406/loons-and-grebes-common-loon-pied-billed-grebe-x-351406.webp)

LOONS and GREBES [ ] Common Loon [ ] Pied-Billed Grebe---X

LOONS and GREBES [ ] Common Merganser [ ] Common Loon [ ] Ruddy Duck---x OWLS [ ] Pied-billed Grebe---x [ ] Barn Owl [ ] Horned Grebe HAWKS, KITES and EAGLES [ ] Eared Grebe [ ] Northern Harrier SWIFTS and HUMMINGBIRDS [ ] Western Grebe [ ] Cooper’s Hawk [ ] White-throated Swift [ ] Clark’s Grebe [ ] Red-shouldered Hawk [ ] Anna’s Hummingbird---x [ ] Red-tailed Hawk KINGFISHERS PELICANS and CORMORANTS [ ] Golden Eagle [ ] Belted Kingfisher [ ] Brown Pelican [ ] American Kestrel [ ] Double-crested Cormorant [ ] White-tailed Kite WOODPECKERS [ ] Acorn Woodpecker BITTERNS, HERONS and EGRETS PHEASANTS and QUAIL [ ] Red-breasted Sapsucker [ ] American Bittern [ ] Ring-necked Pheasant [ ] Nuttall’s Woodpecker---x [ ] Great Blue Heron [ ] California Quail [ ] Great Egret [ ] Downy Woodpecker [ ] Snowy Egret RAILS [ ] Northern Flicker [ ] Sora [ ] Green Heron---x TYRANT FLYCATCHERS [ ] Black-crowned Night-Heron---x [ ] Common Moorhen Pacific-slope Flycatcher [ ] American Coot---x [ ] NEW WORLD VULTURES [ ] Black Phoebe---x Say’s Phoebe [ ] Turkey Vulture SHOREBIRDS [ ] [ ] Killdeer---x [ ] Ash-throated Flycatcher WATERFOWL [ ] Greater Yellowlegs [ ] Western Kingbird [ ] Greater White-fronted Goose [ ] Black-necked Stilt SHRIKES [ ] Ross’s Goose [ ] Spotted Sandpiper Loggerhead Shrike [ ] Canada Goose---x [ ] Least Sandpiper [ ] [ ] Wood Duck [ ] Long-billed Dowitcher VIREOS Gadwall [ ] [ ] Wilson’s Snipe [ ] Warbling Vireo [ ] American Wigeon [ ] Mallard---x GULLS and TERNS JAYS and CROWS [ ] Cinnamon Teal [ ] Mew Gull [ ] Western Scrub-Jay---x -

A Baraminological Analysis of the Land Fowl (Class Aves, Order Galliformes)

Galliform Baraminology 1 Running Head: GALLIFORM BARAMINOLOGY A Baraminological Analysis of the Land Fowl (Class Aves, Order Galliformes) Michelle McConnachie A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2007 Galliform Baraminology 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Timothy R. Brophy, Ph.D. Chairman of Thesis ______________________________ Marcus R. Ross, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Harvey D. Hartman, Th.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Judy R. Sandlin, Ph.D. Assistant Honors Program Director ______________________________ Date Galliform Baraminology 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ, without Whom I would not have had the opportunity of being at this institution or producing this thesis. I would also like to thank my entire committee including Dr. Timothy Brophy, Dr. Marcus Ross, Dr. Harvey Hartman, and Dr. Judy Sandlin. I would especially like to thank Dr. Brophy who patiently guided me through the entire research and writing process and put in many hours working with me on this thesis. Finally, I would like to thank my family for their interest in this project and Robby Mullis for his constant encouragement. Galliform Baraminology 4 Abstract This study investigates the number of galliform bird holobaramins. Criteria used to determine the members of any given holobaramin included a biblical word analysis, statistical baraminology, and hybridization. The biblical search yielded limited biosystematic information; however, since it is a necessary and useful part of baraminology research it is both included and discussed. -

Onetouch 4.0 Scanned Documents

/ Chapter 2 THE FOSSIL RECORD OF BIRDS Storrs L. Olson Department of Vertebrate Zoology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC. I. Introduction 80 II. Archaeopteryx 85 III. Early Cretaceous Birds 87 IV. Hesperornithiformes 89 V. Ichthyornithiformes 91 VI. Other Mesozojc Birds 92 VII. Paleognathous Birds 96 A. The Problem of the Origins of Paleognathous Birds 96 B. The Fossil Record of Paleognathous Birds 104 VIII. The "Basal" Land Bird Assemblage 107 A. Opisthocomidae 109 B. Musophagidae 109 C. Cuculidae HO D. Falconidae HI E. Sagittariidae 112 F. Accipitridae 112 G. Pandionidae 114 H. Galliformes 114 1. Family Incertae Sedis Turnicidae 119 J. Columbiformes 119 K. Psittaciforines 120 L. Family Incertae Sedis Zygodactylidae 121 IX. The "Higher" Land Bird Assemblage 122 A. Coliiformes 124 B. Coraciiformes (Including Trogonidae and Galbulae) 124 C. Strigiformes 129 D. Caprimulgiformes 132 E. Apodiformes 134 F. Family Incertae Sedis Trochilidae 135 G. Order Incertae Sedis Bucerotiformes (Including Upupae) 136 H. Piciformes 138 I. Passeriformes 139 X. The Water Bird Assemblage 141 A. Gruiformes 142 B. Family Incertae Sedis Ardeidae 165 79 Avian Biology, Vol. Vlll ISBN 0-12-249408-3 80 STORES L. OLSON C. Family Incertae Sedis Podicipedidae 168 D. Charadriiformes 169 E. Anseriformes 186 F. Ciconiiformes 188 G. Pelecaniformes 192 H. Procellariiformes 208 I. Gaviiformes 212 J. Sphenisciformes 217 XI. Conclusion 217 References 218 I. Introduction Avian paleontology has long been a poor stepsister to its mammalian counterpart, a fact that may be attributed in some measure to an insufRcien- cy of qualified workers and to the absence in birds of heterodont teeth, on which the greater proportion of the fossil record of mammals is founded. -

Identification and Distribution of Clark's Grebe

IDENTIFICATION AND DISTRIBUTION OF CLARK'S GREBE JOHN T. RA'Frl, Wildlife Biology, Washington State University, Pullman, Washington99164 For nearly 100 years ornithologists have considered the genus Aechmophorusto includeonly one species,the WesternGrebe (A. occiden- talis). Few ornithologists,especially amateur field ornithologists,have been aware that the WesternGrebe has been consideredpolymorphic, with two distinctphenotypes referred to as dark and light phases (Storer 1965, Mayr and Short 1970). Recent study of sympatricdark-phase and light-phasepopulations indi- catesthe polymorphismclassification is erroneousand that the forms func- tion as separate species(Ratti 1979). Additional data are needed on dark- phaseand light-phasebirds, and hopefullythis paper will aid in alertingboth professionaland amateurornithologists to the identificationand distribution of these species. LITERATURE REVIEW George N. Lawrence (in Baird 1858:894-895) originallydescribed the two grebeforms as separatespecies, calling the dark form the WesternGrebe (Podicepsoccidentalis) and the light form Clark'sGrebe (Podicepsclarkii). However, Coues (1874) and Henshaw (1881) suggestedthat the formswere color phases of the same species,and the American Ornithologists'Union (1886, 1931, 1957) classifiedthe forms as a singlespecies. Mayr and Short (1970:88) attributedthe variationto "scatteredpolymorphism." Both Storer (1965) and Lindvall (1976) reported assortativemating by WesternGrebes in Utah -- the tendencyof birdsto mate with individualsof the same phenotype. -

1 ID Euring Latin Binomial English Name Phenology Galliformes

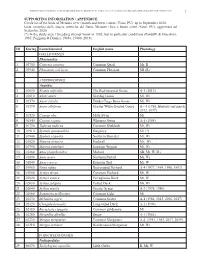

BIRDS OF METAURO RIVER: A GREAT ORNITHOLOGICAL DIVERSITY IN A SMALL ITALIAN URBANIZING BIOTOPE, REQUIRING GREATER PROTECTION 1 SUPPORTING INFORMATION / APPENDICE Check list of the birds of Metauro river (mouth and lower course / Fano, PU), up to September 2020. Lista completa delle specie ornitiche del fiume Metauro (foce e basso corso /Fano, PU), aggiornata ad Settembre 2020. (*) In the study area 1 breeding attempt know in 1985, but in particolar conditions (Pandolfi & Giacchini, 1985; Poggiani & Dionisi, 1988a, 1988b, 2019). ID Euring Latin binomial English name Phenology GALLIFORMES Phasianidae 1 03700 Coturnix coturnix Common Quail Mr, B 2 03940 Phasianus colchicus Common Pheasant SB (R) ANSERIFORMES Anatidae 3 01690 Branta ruficollis The Red-breasted Goose A-1 (2012) 4 01610 Anser anser Greylag Goose Mi, Wi 5 01570 Anser fabalis Tundra/Taiga Bean Goose Mi, Wi 6 01590 Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose A – 4 (1986, february and march 2012, 2017) 7 01520 Cygnus olor Mute Swan Mi 8 01540 Cygnus cygnus Whooper Swan A-1 (1984) 9 01730 Tadorna tadorna Common Shelduck Mr, Wi 10 01910 Spatula querquedula Garganey Mr (*) 11 01940 Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mr, Wi 12 01820 Mareca strepera Gadwall Mr, Wi 13 01790 Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mr, Wi 14 01860 Anas platyrhynchos Mallard SB, Mr, W (R) 15 01890 Anas acuta Northern Pintail Mi, Wi 16 01840 Anas crecca Eurasian Teal Mr, W 17 01960 Netta rufina Red-crested Pochard A-4 (1977, 1994, 1996, 1997) 18 01980 Aythya ferina Common Pochard Mr, W 19 02020 Aythya nyroca Ferruginous -

Bird Observer

Bird Observer VOLUME 39, NUMBER 2 APRIL 2011 HOT BIRDS On November 20 the Hampshire Bird Club was waiting at Quabbin headquarters for the rest of the group to arrive when Larry Therrien spotted a flock of 19 swans in the distance— Tundra Swans! Ian Davies took this photograph (left). Since 2003 Cave Swallows have been a specialty of November, showing up in coastal locations in increasing numbers over the years. This year there was a flurry of reports along the New England coast. On Thanksgiving Day, Margo Goetschkes took this photograph (right) of one of the birds at Salisbury. On November 30, Vern Laux got a call from a contractor reporting a “funny bird” at the Nantucket dump. Vern hustled over and was rewarded with great views of this Fork-tailed Flycatcher (left). Imagine: you’re photographing a Rough- legged Hawk in flight, and all of a sudden it is being mobbed—by a Northern Lapwing (right)! That’s what happened to Jim Hully on December 2 on Plum Island. This is only the second state record for this species, the first being in Chilmark in December of 1996. On April 9, Keelin Miller found an interesting gull at Kalmus Beach in Hyannis. As photographs were circulated, opinions shifted toward a Yellow-legged Gull (left). Check out Jeremiah Trimble’s photo from April 13. CONTENTS BIRDING THE LAKEVILLE PONDS OF PLYMOUTH COUNTY, MASSACHUSETTS Jim Sweeney 73 THE FINAL YEAR OF THE BREEDING BIRD ATLAS: GOING OVER THE TOP John Galluzzo 83 37 YEARS OF NIGHTHAWKING Tom Gagnon 86 LEIF J ROBINSON: MAY 21, 1939 – FEBRUARY 28, 2011 Soheil Zendeh 93 FIELD NOTES Double-crested Cormorant Has Trouble Eating a Walking Catfish William E. -

Appendix A. Supplementary Material

Appendix A. Supplementary material Comprehensive taxon sampling and vetted fossils help clarify the time tree of shorebirds (Aves, Charadriiformes) David Cernˇ y´ 1,* & Rossy Natale2 1Department of the Geophysical Sciences, University of Chicago, Chicago 60637, USA 2Department of Organismal Biology & Anatomy, University of Chicago, Chicago 60637, USA *Corresponding Author. Email: [email protected] Contents 1 Fossil Calibrations 2 1.1 Calibrations used . .2 1.2 Rejected calibrations . 22 2 Outgroup sequences 30 2.1 Neornithine outgroups . 33 2.2 Non-neornithine outgroups . 39 3 Supplementary Methods 72 4 Supplementary Figures and Tables 74 5 Image Credits 91 References 99 1 1 Fossil Calibrations 1.1 Calibrations used Calibration 1 Node calibrated. MRCA of Uria aalge and Uria lomvia. Fossil taxon. Uria lomvia (Linnaeus, 1758). Specimen. CASG 71892 (referred specimen; Olson, 2013), California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco, CA, USA. Lower bound. 2.58 Ma. Phylogenetic justification. As in Smith (2015). Age justification. The status of CASG 71892 as the oldest known record of either of the two spp. of Uria was recently confirmed by the review of Watanabe et al. (2016). The younger of the two marine transgressions at the Tolstoi Point corresponds to the Bigbendian transgression (Olson, 2013), which contains the Gauss-Matuyama magnetostratigraphic boundary (Kaufman and Brigham-Grette, 1993). Attempts to date this reversal have been recently reviewed by Ohno et al. (2012); Singer (2014), and Head (2019). In particular, Deino et al. (2006) were able to tightly bracket the age of the reversal using high-precision 40Ar/39Ar dating of two tuffs in normally and reversely magnetized lacustrine sediments from Kenya, obtaining a value of 2.589 ± 0.003 Ma.