Case Study the Toyota Group and the Aisin Fire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Facilities Licensed by the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV)

Facilities Licensed by the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) Facility # Facility Name Facility Name Overflow 7059327 ADESA BUFFALO 7104415 BVC RACING LLC 7127358 COLLAZO AUTO SALES 7121893 CROSS BRONX AUTOMOTIVE INC 7105906 ACCORD AUTO SALES 3470164 DALE PENNINGS GARAGE 7099259 DAVES TOWING SPECIALISTS INC 7126716 DERRIGO S SERVICE CENTER INC 7004571 DICKS COLLSION LLC 7105124 DREAM TECH AUTO SERVICE INC 4090002 BENEDICT CORP 7037979 EAGLE BEVERAGE CO INC 7054769 FRANKS AUTO SERVICE 7066748 ELITE AUTOMOTIVE 7070361 ELITE AUTO SALES 7112741 ELITE AUTO WORKS NY INC 7044804 ESLERS GARAGE 7126673 EVERGREEN MOTORCARS LLC 7103126 EVOLUTION AUTO 7047915 FINGER LAKES RCRTNL VEHICLES INC Page 1 of 1520 09/26/2021 Facilities Licensed by the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) Facility Street Facility City Facility State 12200 MAIN ST AKRON NY 4164 ROUTE 22 PLATTSBURG NY 699 PULLMAN AVE ST A ROCHESTER NY 1810 CROSS BX EXPWY BRONX NY 5185 ROUTE 209 ACCORD NY 192-194 HETCHLTWN RD SCOTIA NY 41 RT 236 CLIFTON PARK NY 14483 NYS ROUTE 193 MANNSVILLE NY 189 IRISH SETTLMNT R PLATTSBURGH NY 101-08 43RD AVENUE CORONA NY POB350 E RIVER RD NORWICH NY W 5 ST RD BX 1035 OSWEGO NY RT 374 BX 101A MERRILL NY PB39 ERNEST RD SUMMIT NY 2520 NIAGARA FLLS BL TONAWANDA NY 2050 ROUTE 17A GOSHEN NY 231 SOUTHMAIN ST NORTHVILLE NY 3199 ALBY PST 137C BUCHANAN NY POB 92 36 S WEST ST CORTLAND NY RD 9 RT 247 CANANDAIGUA NY Page 2 of 1520 09/26/2021 Facilities Licensed by the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) Facility Zip Code Facility County Owner Name 14001 ERIE ADESA NEW YORK -

Alpha ELT Listing

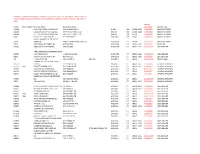

Lienholder Name Lienholder Address City State Zip ELT ID 1ST ADVANTAGE FCU PO BX 2116 NEWPORT NEWS VA 23609 CFW 1ST COMMAND BK PO BX 901041 FORT WORTH TX 76101 FXQ 1ST FNCL BK USA 47 SHERMAN HILL RD WOODBURY CT 06798 GVY 1ST LIBERTY FCU PO BX 5002 GREAT FALLS MT 59403 ESY 1ST NORTHERN CA CU 1111 PINE ST MARTINEZ CA 94553 EUZ 1ST NORTHERN CR U 230 W MONROE ST STE 2850 CHICAGO IL 60606 GVK 1ST RESOURCE CU 47 W OXMOOR RD BIRMINGHAM AL 35209 DYW 1ST SECURITY BK WA PO BX 97000 LYNNWOOD WA 98046 FTK 1ST UNITED SVCS CU 5901 GIBRALTAR DR PLEASANTON CA 94588 W95 1ST VALLEY CU 401 W SECOND ST SN BERNRDNO CA 92401 K31 360 EQUIP FIN LLC 300 BEARDSLEY LN STE D201 AUSTIN TX 78746 DJH 360 FCU PO BX 273 WINDSOR LOCKS CT 06096 DBG 4FRONT CU PO BX 795 TRAVERSE CITY MI 49685 FBU 777 EQUIPMENT FIN LLC 600 BRICKELL AVE FL 19 MIAMI FL 33131 FYD A C AUTOPAY PO BX 40409 DENVER CO 80204 CWX A L FNCL CORP PO BX 11907 SANTA ANA CA 92711 J68 A L FNCL CORP PO BX 51466 ONTARIO CA 91761 J90 A L FNCL CORP PO BX 255128 SACRAMENTO CA 95865 J93 A L FNCL CORP PO BX 28248 FRESNO CA 93729 J95 A PLUS FCU PO BX 14867 AUSTIN TX 78761 AYV A PLUS LOANS 500 3RD ST W SACRAMENTO CA 95605 GCC A/M FNCL PO BX 1474 CLOVIS CA 93613 A94 AAA FCU PO BX 3788 SOUTH BEND IN 46619 CSM AAC CU 177 WILSON AVE NW GRAND RAPIDS MI 49534 GET AAFCU PO BX 619001 MD2100 DFW AIRPORT TX 75261 A90 ABLE INC 503 COLORADO ST AUSTIN TX 78701 CVD ABNB FCU 830 GREENBRIER CIR CHESAPEAKE VA 23320 CXE ABOUND FCU PO BX 900 RADCLIFF KY 40159 GKB ACADEMY BANK NA PO BX 26458 KANSAS CITY MO 64196 ATF ACCENTRA CU 400 4TH -

IMC Sustainability Report 2019

INDUS MOTOR COMPANY LTD. INDUS MOTOR COMPANY LTD. INDUS MOTOR COMPANY LTD. 2018 | SUSTAINABILITY REPORT About this Report This is the 4th Sustainability Report of Indus Motor Company Limited (IMC). It encompasses the activities and impacts of IMC covering the period of the financial year 2019, starting from July 01, 2018 to June 30, 2019. IMC equally weighs the impact and contributions of its non-financial activities along with financial results to measure the success of the Company during the period. This report includes information about IMC’s operations covering assembly of Passenger Cars (Corolla), Light Commercial Vehicles (Hilux) and SUV (Fortuner) of the Toyota brand, our approach to sustainability, relationship with key stakeholders, contribution and impacts on economic development, environment and society and details of our plans and ambitions for the future. GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards, international best practices and “Ten Principles” of UNGC guide the compilation of this report. The GRI Standards Reporting Principles - for defining reporting content and quality of the reported INDUS MOTOR COMPANY LTD. information – from GR 101: Foundation 2016 have been applied. The information about the process of defining the Report content and boundaries of the material topics can be found in the materiality analysis section of the Report. The data included in the Report is based on scientific measurement on actual basis. However, where data was not available, estimation has been used. The data collection and measurement techniques are applied consistently over the periods. There were no significant changes to the size and structure or ownership of IMC during the reporting period. There were no changes in the reporting period, scope and boundary of material topics. -

Indus Motor Company Ltd. 2016 Annual Report THINGS to DO for PAKISTAN at Indus Motor Company, We Believe in Setting Goals That Create Value for Pakistan

Indus Motor Company Ltd. 2016 annual report THINGS TO DO FOR PAKISTAN At Indus Motor Company, we believe in setting goals that create value for Pakistan. As a good corporate citizen we strive to play an ever increasing role in our society by integrating our business, our society and our people as a force that aims to lead Pakistan towards a better tomorrow. Delight people of Pakistan with Improve Access to Education for mobility solutions the people of Pakistan Make More and More of Our Cars Extend a helping hand in times in Pakistan of need Make Toyota Cars with the people Promote a Cleaner, Greener Future of Pakistan Corporate Profile IMC was incorporated in 1989 as a joint venture company between the House of Habib of Pakistan, Toyota Motor Corporation and Toyota Tsusho Corporation of Japan. The Company manufactures and markets Toyota brand vehicles in Pakistan. The main product offerings include several variants of the flagship ‘Corolla’ in the passenger cars category, ‘Hilux’ in the light commercial vehicles segment and ‘Fortuner’ Sports Utility Vehicle. The manufacturing facility and offices are located at a 105 acre site in Port Qasim, Karachi, while the product is delivered to end customers nationwide through a strong network of 43 independent 3S Dealerships spread across the country. In its 26 years since inception, IMC has sold more than 600,000 CBU/CKD vehicles and has demonstrated impressive growth, in terms of volumetric increase from a modest beginning of 20 vehicles per day production in 1993 to 240 units daily at present through the development of human talent embracing the ‘Toyota Way’ of quality and lean manufacturing. -

Toyota Corolla Altis.Pdf

Toyota Central Motors New Toyota Corolla ALTIS 1599cc Petrol Toyota Central Motors New Toyota Corolla ALTIS 1599cc Petrol ALTIS 1.6L 6 Speed Manual Transmission (ALTIS MT) Colors : White, Black, Strong Blue Met., Gun Metallic, Flaxen Mica Met., Medium Silver, Olive Green, Wine Red(New), Deep Blue(New) Transmission : Manual Unit Price : Rs. 1,902,500/- Standard Accessories: Brand New Toyota Corolla ALTIS 1599cc Petrol Dual VVT-i Engine, 121 HP 6 Speed Manual transmission EPS (Electric Power Steering) tilt & telescopic CD player/AM-FM/MP3 with 6 speakers Hi Grade Fabric Seats, Backlit Optitron Meter with MID Wooden Paneling Sliding Arm Rest, Power windows & Central locking Retractable side mirrors Extended Side Skirts, Integrated signal lamps on side mirrors Rear LED Lights, Fog Lights, Keyless Entry SRS Air Bag, 195/65R15 alloy rims, ABS (Anti-Lock Braking System) with EBD and Brake Assist, 15 inch Disc Brakes (Front + Rear), 55L fuel tank capacity. Note: 1. For Individual Customer : Copy of NIC is required. 2. For Corporate Customer : Purchase Order, copy of NTN Certificate and copy of Sales Tax Registration is required. 3. Colors/specifications are subject to change without any prior notice. 4. Payment 100% advance by Pay Order/Bank Draft in favor of INDUS MOTOR CO. LTD. A/c of (Customer Name) 5. The above price are provisional and are subject to change without any prior notice, price prevailing at the time of delivery will be final. Toyota Central Motors New Toyota Corolla ALTIS 1599cc Petrol ALTIS 1.6L 6 Speed Manual With Sun Roof (ALTIS MT SR) Colors : White, Black, Strong Blue Met., Gun Metallic, Flaxen Mica Met., Medium Silver, Olive Green, Wine Red(New), Deep Blue(New) Transmission : Manual Unit Price : Rs. -

UNITED NATIONS SYSTEM Annual Statistical Report 2005

Annual Statistical Report 2005 • Procurement of Goods & Services • All Sources of Funding • UNDP Funding • Procurement from DAC Member Countries • International & National Project Personnel • United Nations Volunteers • Fellowships Published: July 2006 by UNITED NATIONS SYSTEM Annual Statistical Report 2005 Procurement of Goods and Services • All Sources of Funding • UNDP Funding Procurement from DAC Member Countries International & National Project Personnel United Nations Volunteers Fellowships July 2006 Copyright © 2006 by the United Nations Development Programme 1 UN Plaza, New York, NY 10017, USA All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of UNDP/IAPSO. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................... 1 GLOASSARY OF TERMS ...................................................................................................... 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: ALL SOURCES OF FUNDING (UN SYSTEM)............................ 4 PROCUREMENT OF GOODS AND SERVICES - ALL SOURCES OF FUNDING Procurement of goods by country of procurement and services by country of head office ................................................................................................... 9 Procurement by UN agency ...................................................................................... -

Facilities Licensed by the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV)

Facilities Licensed by the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) Facility # Facility Name Facility Name Overflow 7059327 ADESA BUFFALO 7104415 BVC RACING LLC 7127358 COLLAZO AUTO SALES 7121893 CROSS BRONX AUTOMOTIVE INC 7105906 ACCORD AUTO SALES 3470164 DALE PENNINGS GARAGE 7099259 DAVES TOWING SPECIALISTS INC 7126716 DERRIGO S SERVICE CENTER INC 7004571 DICKS COLLSION LLC 7105124 DREAM TECH AUTO SERVICE INC 4090002 BENEDICT CORP 7037979 EAGLE BEVERAGE CO INC 7054769 FRANKS AUTO SERVICE 7066748 ELITE AUTOMOTIVE 7070361 ELITE AUTO SALES 7112741 ELITE AUTO WORKS NY INC 7044804 ESLERS GARAGE 7126673 EVERGREEN MOTORCARS LLC 7103126 EVOLUTION AUTO 7047915 FINGER LAKES RCRTNL VEHICLES INC Page 1 of 1520 10/02/2021 Facilities Licensed by the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) Facility Street Facility City Facility State 12200 MAIN ST AKRON NY 4164 ROUTE 22 PLATTSBURG NY 699 PULLMAN AVE ST A ROCHESTER NY 1810 CROSS BX EXPWY BRONX NY 5185 ROUTE 209 ACCORD NY 192-194 HETCHLTWN RD SCOTIA NY 41 RT 236 CLIFTON PARK NY 14483 NYS ROUTE 193 MANNSVILLE NY 189 IRISH SETTLMNT R PLATTSBURGH NY 101-08 43RD AVENUE CORONA NY POB350 E RIVER RD NORWICH NY W 5 ST RD BX 1035 OSWEGO NY RT 374 BX 101A MERRILL NY PB39 ERNEST RD SUMMIT NY 2520 NIAGARA FLLS BL TONAWANDA NY 2050 ROUTE 17A GOSHEN NY 231 SOUTHMAIN ST NORTHVILLE NY 3199 ALBY PST 137C BUCHANAN NY POB 92 36 S WEST ST CORTLAND NY RD 9 RT 247 CANANDAIGUA NY Page 2 of 1520 10/02/2021 Facilities Licensed by the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) Facility Zip Code Facility County Owner Name 14001 ERIE ADESA NEW YORK -

Dealer Conveyance Fees Charged by New and Used Car Dealers in Connecticut and Related Information

Dealer Conveyance Fees Charged by New and Used Car Dealers in Connecticut and Related Information Report to Transportation Committee Required by Public Act 15-5, Section 428 (June Special Session) January 15, 2016 By Legislative Program Review and Investigations Committee Connecticut General Assembly State Capitol Room 506 Hartford, CT 06106 Page intentionally blank Page intentionally blank Highlights of Dealer Conveyance Fee Report • Section 428 of PA 15-5 JSS required this report by the Legislative Program Review and Investigations Committee (PRI), in addition to requiring new and used car dealers to submit dealer conveyance fee information to the legislature via PRI on a one-time basis by November 1, 2015. • Most new and used license holders provided information for this survey. o The survey response rate for licensed new and used car dealers was 87% and 76%, respectively, with an overall response rate of 78%. • Dealers selling new cars charge a higher dealer conveyance fee than dealers selling used cars or other motor vehicles (e.g., motorcycles, RVs). The average dealer conveyance fee for dealers selling: o new cars was $405 (range of $0 to $699); o used cars was $131 (range of $0 to $695); and o other motor vehicles, $119 (range of $0 to $499). • Over 80% of new car dealers charge over $300, and over 70% of used car dealers charge under $199. • No dealer conveyance fee is charged by 47% of used car dealers, 45% of other motor vehicles, and just 5% of new car dealers. • For most dealers, there was little variability from month to month in the average dealer conveyance fee paid by customers from October 2014 through September 2015. -

Lic No. DBA Indicator Business Name Business Address License

Connecticut Dealer and Repairer License List as of 09/27/2021 - PLEASE NOTE THAT LICENSEES HAVE 45 DAYS FROM EXPIRATION DATE TO RENEW LICENSE BEFORE LICENSE IS CANCELED BY DMV License Lic No. DBA Indicator Business Name Business Address Expiration License Type M1026 SPARTAN CARGO TRAILERS LLC 140 BUSINESS BLVD ALMA GA 31510-7667 6/30/2023 MANUFACTURER M1013 EAGLE SPECIALTY VEHICLES LLC 3344 STATE ROUTE 132 AMELIA OH 45102-2249 6/30/2022 MANUFACTURER M1014 KELLERMAN COACHWORKS INC 3344 STATE ROUTE 134 AMELIA OH 45102 6/30/2022 MANUFACTURER M942 KTM NORTH AMERICA INC 1119 MILAN AVE AMHERST OH 44001 6/30/2023 MANUFACTURER ISUZU COMMERCIAL TRUCK OF M801 AMERICA 1400 S DOUGLASS RD STE 100 ANAHEIM CA 92806 6/30/2023 MANUFACTURER J2629 ANDOVER AUTO PARTS INC 497 ROUTE 6 ANDOVER CT 06232-1320 4/30/2022 RECYCLER U5236 DUBOIS AUTOMOTIVE INC 343 ROUTE 6 ANDOVER CT 06232-1319 12/31/2022 USED DEALER X PRO MOTORCYCLE PERFORMANCE U8237 TECHNOLOGY INC 5 BUNKER HILL RD ANDOVER CT 06232-1334 11/30/2022 USED DEALER U960 ANDOVER AUTO PARTS INC 497 ROUTE 6 ANDOVER CT 06232-1320 8/31/2023 USED DEALER N2 FITZPATRICKS INC 430 E MAIN ST BOX 206 ANSONIA CT 06401 11/30/2021 NEW DEALER CONN DEPT EDUCATION EMMETT R1371 OBRIEN 141 PRINDLE AVE ANSONIA CT 06401-2561 2/28/2023 GENERAL REPAIRER R1371 DBA EMMETT OBRIEN RVTS 141 PRINDLE AVE ANSONIA CT 06401-2561 2/28/2023 GENERAL REPAIRER R4508 V AND M INC OF ANSONIA 472 MAIN ST ANSONIA CT 06401 8/31/2022 GENERAL REPAIRER R6524 CHIPPYS SERVICE STATION LLC 136 WAKELEE AVE ANSONIA CT 06401 6/30/2022 GENERAL REPAIRER R6826 -

Annual Report PROGRESSING with Localization

2018 annual report PROGRESSING with Localization IMC’s financial highlights were further improved than previous years and have observed increased turnover and profitability. IMC has been a major contributor towards economic progress in our country, with its focus on empowering the local market for parts. With the launch of two new models this year, the Fortuner and Hilux REVO, our localization has gone even further. With a constant increase in local suppliers, IMC has come a long way from just 15 parts suppliers in 1993 to 45 in 2018. Let us share some of the facts with you on our journey to progress as the theme of our annual report this year. Corporate Profile Indus Motor Company Limited (IMC) was incorporated in 1989 as a joint venture company between certain companies of House of Habib of Pakistan, Toyota Motor Corporation and Toyota Tsusho Corporation of Japan. The Company manufactures and markets Toyota brand vehicles in Pakistan. The main product offerings include several variants of the flagship ‘Corolla’ in the passenger car category, ‘Hilux’ in the light commercial vehicle segment and the ‘Fortuner’ Sports Utility Vehicle. The manufacturing facility and offices are located at a 105 acre site in Port Qasim, Karachi, while the product is delivered to end customers nationwide through a strong network of 45 independent 3S Dealerships spread across the country. In its 29 years history since inception, IMC has sold more than 800,000 CBU/CKD vehicles and has demonstrated impressive growth, in terms of volumetric increase from a modest beginning of 20 vehicles per day production in 1993 to 268 (with overtime) units daily at present through the development of human talent embracing the ‘Toyota Way’ of quality and lean manufacturing. -

Toyota Central Motors New Toyota Fortunier

Toyota Central Motors New Toyota Fortunier Toyota Central Motors New Toyota Fortunier Fortuner 2.7L VVT-I Auto Transmission Colors : White, Black, Strong Blue Met., Gun Metallic, Flaxen Mica Met., Medium Silver, Olive Green, Wine Red(New), Deep Blue(New) Transmission : Automatic Unit Price : Rs. 5,748,500/- Brand New Toyota Fortuner 2.7L Petrol, Full Time 4WD with Center Differential Lock, Modern Technology VVT-i & ETCS-i, 158 HP, 4 Speed Automatic transmission with ECT, Complete Chrome Package, Projected Head Lamps, Fog Lights, Roof Rail, Rear Spoiler, 265/65/R17 Alloy Rims, Full Beige Leather interior, Adjustable Headrest, 6 Ways Power Driver Seat (Recline, lift, slide), 7 inch wide Touch Screen DVD Entertainment System with GPS Navigation & Rear view Camera, 6 Speakers, LED Optitron Meter with Chrome Ring & Illumination Control, MID, Powerful Dual A/C with front & Rear controls, Audio Switches on Steering, 2 Airbags (D+P), Black Wooden grain Paneling, Power windows, Central locking, Retractable Side Mirrors, Immobilizer with Keyless Entry, ABS (Anti-Lock Braking System), 65L fuel tank capacity. Note: 1. For Individual Customer : Copy of NIC is required. 2. For Corporate Customer : Purchase Order, copy of NTN Certificate and copy of Sales Tax Registration is required. 3. Colors/specifications are subject to change without any prior notice. 4. Payment 100% advance by Pay Order/Bank Draft in favor of INDUS MOTOR CO. LTD. A/c of (Customer Name) 5. The above price are provisional and are subject to change without any prior notice, price prevailing at the time of delivery will be final. . -

Japanese Automobile Industry.Cdr

February 2015 | Volume 2 | Issue 2 JapaneseCarTrade.com Japanese Used Cars Portal JAPAN Automobile Industry Silver Jubilee E im Group 1989-2014 Latest Technology Years in Japan Auto Industry 25Dedicated to Japan JapaneseCarTrade.com History of Japan Auto Industry 2 JapaneseCarTrade.com February 2015 C o n t e n t s Japan Automobile Industry ............................................................................................................ 3-4 25 Years Success Story........................................................................................................................5-6 History of Japan Automobile Industry ............................................................................. 7-9 Japan Automobile Manufacturers..................................................................................... 12-17 Latest Technology in Japan Auto Industries ...................................................... 18-21 Japan Used Automobile Trade ......................................................................................... 22-25 Company Introduction.............................................................................................................................. 26 Future of Automobile Industry ........................................................................................27-28 Japan Automobile Production by Vehicle Type - 2014 ................................29 Japan Automobile Production by Manufacture in 2013-14 ......................29 Japan Used Automobile Export Worldwide in Year 2014...........................