The Garters and the Garter Achievements of Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy with an Appendix on Edward IV’S Additions to the Statutes of the Order of the Garter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swiss Independence1

1 Primary Source 10.2 SWISS INDEPENDENCE1 During the first half of the fourteenth century, eight Swiss cantons, or states, joined together in alliances in order to protect their autonomy from surrounding feudal lords. Starting around 1450, more cantons joined them as they resisted the powers of the duke of Burgundy—Charles the Bold (1433–77)—, Duke Sigismund (1427–96) of Habsburg of Austria, and King Louis XI of France (r. 1461–83). These powers feared the territorial expansion of the Swiss Confederation, as well as the ideas of independence present in them. The Swiss confederates played their enemies against each other, and eventually sided with Sigismund to counter the expansion of Charles the Bold. Charles’s lost lands became part of France, and the Swiss Confederation gained independence from the Hapsburg Empire. Slightly over two decades later, the Swiss states received complete autonomy from the Holy Roman Empire as well. Although the individual Swiss cantons would govern themselves independently of the others, the Swiss Confederation did gradually develop a political assembly of representatives from each canton that would come to determine common policies and settle disputes. Below is an excerpt that depicts the struggle between Charles the Bold and the Swiss during the Burgundian Wars, which were fought from 1474 to 1477. For the excerpted text online, click here. For the original text from which the passage below was excerpted, volume 2 of The Memoirs of Philippe de Commynes, Lord of Argenton, click here. CHARLES THE BOLD OF BURGUNDY AND THE SWISS What ease or what pleasure did Charles, duke of Burgundy, enjoy more than our master, King Louis? In his youth, indeed, he had less trouble, for he did not begin to enter upon any action till nearly the two-and-thirtieth year of his age; so that before that time he lived in great ease and quiet . -

Wilhelm Tell 1789 — 1895

THE RE-APPROPRIATION AND TRANSFORMATION OF A NATIONAL SYMBOL: WILHELM TELL 1789 — 1895 by RETO TSCHAN B.A., The University of Toronto, 1998 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of History) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 2000 © Reto Tschan, 2000. In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the library shall make it freely available for reference and study. 1 further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of 'HvS.'hK^ The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date l^.+. 2000. 11 Abstract Wilhelm Tell, the rugged mountain peasant armed with his crossbow, is the quintessential symbol of Switzerland. He personifies both Switzerland's ancient liberty and the concept of an armed Swiss citizenry. His likeness is everywhere in modern Switzerland and his symbolic value is clearly understood: patriotism, independence, self-defense. Tell's status as the preeminent national symbol of Switzerland is, however, relatively new. While enlightened reformers of the eighteenth century cultivated the image of Tell for patriotic purposes, it was, in fact, during the French occupation of Switzerland that Wilhelm Tell emerged as a national symbol. -

Spotlights Celebrating the Swiss

Spotlight on the Middle Ages Celebrating the Swiss DR. JÖRN GÜNTHER · RARE BOOKS AG Manuscripts & Rare Books Basel & Stalden www.guenther-rarebooks.com [email protected] Celebrating the Foundation of the Old Confederacy On August 1st the Swiss celebrate what is called the Schweizer Bundesfeiertag - Fête nationale suisse - Festa nazionale svizzera - Fiasta naziunala svizra. It is inspired by the date of the Pacte du Grutli, the first federal charter concluded in ‘early August’ 1291 when the three Alpine Waldstätten, Schwyz, Uri, and Unterwald swore an oath of mutual military assistance. Petermann Etterlin. Kronica von der loblichen Eydtgnoschaft, Ir harkommen und sust seltzam stritten und geschichten. Basel: Michael Furter, 24 December 1507. 1st edition, 2nd issue. Several pacts of the mid-13th to mid-14th century attest to a growing collaboration between cantons. These pacts marked decisions of pragmatic alliances and initiated what became a permanent, sworn confederacy: the Old Swiss Confederacy. The Alte Eidgenossenschaft began as a loose confederacy of three independent, small states within the Holy Roman Empire. Formed from this nucleus of three oath-takers in central Switzerland, the Eidgenossenschaft soon also included the cities of Zürich and Berne. During the 16th century, the figures – or personifications – of the three Eidgenossen merged with the legend of William Tell and became known as ‘the three Tells’. The legend of the hero William Tell is recorded first in the ‘Weissenbuch’ of Sarnen (Obwalden), written by Hans Schriber (1472). Tell, who is said to have shot an apple from his son's head, also appears in the song ‘Lied von der Eidgenossenschaft’ (‘Tellenlied’ or ‘Bundeslied’, c. -

The Trial of Peter Von Hagenbach: Reconciling History, Historiography, and International Criminal Law

THE TRIAL OF PETER VON HAGENBACH: RECONCILING HISTORY, HISTORIOGRAPHY, AND INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL LAW Gregory S. Gordon* I. INTRODUCTION It is an article of faith among transnational penal experts that Sir Peter von Hagenbach's 1474 prosecution in Breisach for atrocities committed serving the Duke of Burgundy constitutes the first international war crimes trial in history. Hagenbach was tried before an ad hoc tribunal of twenty-eight judges from various regional city-states for misdeeds, including murder and rape, he allegedly perpetrated as governor of the Duke's Alsatian territories from 1469 to 1474. Though it remains obscure in the popular imagination, most legal scholars perceive the trial as a landmark event. Some value it for formulating an embryonic version of crimes against humanity. Others praise it for ostensibly charging rape as a war crime. And all are in agreement that it is the first recorded case in history to reject the defense of superior orders. Such a perspective has arguably helped invest the Nuremberg trials with greater historical legitimacy and lent subtle sanction to the development of international criminal law in the post-Cold War world. But the legal literature typically deals with the trial in very cursory fashion and its stature as pre-Nuremberg precedent may hinge on faulty assumptions. As the 1990s explosion of ad hoc tribunal activity is nearing its end and the legal academy is taking stock of its accomplishments and failures, it is perhaps time to look more closely at the Hagenbach trial. This piece will do that by digging below the surface and revisiting some of the historical and legal premises underlying the trial's perception by legal academics. -

The Age of Wars of Religion, 1000-1650

THE AGE OF WARS OF RELIGION, 1000–1650 THE AGE OF WARS OF RELIGION, 1000–1650 AN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF GLOBAL WARFARE AND CIVILIZATION Volume 1, A–K Cathal J. Nolan Greenwood Encyclopedias of Modern World Wars GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Nolan, Cathal J. The age of wars of religion, 1000–1650 : an encyclopedia of global warfare and civilization / Cathal J. Nolan. p. cm.—(Greenwood encyclopedias of modern world wars) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–313–33045–X (set)—ISBN 0–313–33733–0 (vol. 1)— ISBN 0–313–33734–9 (vol. 2) 1. Middle Ages—History—Encyclopedias. 2. History, Modern—17th century— Encyclopedias. 3. Military history, Medieval—Encyclopedias. 4. Military history, Modern—17th century—Encyclopedias. 5. Biography—Middle Ages, 500–1500— Encyclopedias. 6. Biography—17th century—Encyclopedias. I. Title. D114.N66 2006 909.0703—dc22 2005031626 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright # 2006 by Cathal J. Nolan All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2005031626 ISBN: 0–313–33045–X (set) 0–313–33733–0 (vol. I) 0–313–33734–9 (vol. II) First published in 2006 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). -

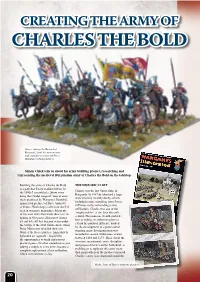

Creating the Army of Charles the Bold

CREATING THE ARMY OF CHARLES THE BOLD Above: Antony the Bastard of Burgundy, leads his men-at-arms and coustillers (converted Perry Miniatures 28mm plastics). Simon Chick tells us about his army building project, researching and representing the medieval Burgundian army of Charles the Bold on the tabletop. Building the army of Charles the Bold THE HISTORICAL BIT is a path that I have trodden before. In Charles was the last Valois duke of the 1990s I assembled a 28mm army Burgundy. In 1467 he inherited a large using the Citadel range of ‘men at arms’ and extremely wealthy duchy, which (now produced by Wargames Foundry), included estates stretching from Savoy inspired by pictures of Dave Andrews in France to the rich trading towns of Games Workshop’s collection that I’d of Flanders. Charles was one of the seen in wargame magazines. Elements ‘mighty nobles’ of the later fifteenth of my own army then made their way to century. His immense wealth enabled feature in Wargames Illustrated (issues him to indulge in ambitious plans to 63 and 64). All that became water-under- extend his political influence backed the-bridge at the 2011 Salute show, when by the development of a professional Perry Miniatures revealed their first standing army. Its organisation was Wars of the Roses plastics. Immediately recorded in several Ordinances written I planned an ‘upgrade’, inspired by between 1468 and 1473. These detail the the opportunities to build and convert structure, recruitment, arms, discipline plastic figures. So what started out as just and proposed tactics on the battlefield, so adding a couple of extra units, became a enabling us to replicate this army more complete replacement of my collection, than many others of the mediaeval period. -

GIPE-002621-Contents.Pdf (1.021Mb)

Dhananjayarao Gadgil Library IIIIIIIIIIIIIII~ 1IIIIImllllllllllili GIPE-PUNE-002621 r E STOR.Y OF THE NATIONS ~ c €be ~tOtP of tbe .taations . • ~ S ITZERLAND. • • • THE STORY OF THE ~ATIONS. I. ROD. By AnTHUR GILliAN. 29. THE NORDIANS. By SARAII M.A. O({NE JEWETT • •. THE JEWS. By Prof. J. K ,;0. THE BYZAlI'TDIE EMl'IRE. HOSMER. llv C. W. C. OMAN. 3. GERlIlANY. By Rev. S. BARI""" 31. SICiLy: PhClOniciaa, Greek ""d GOULD, M.A. Roman. By Ihe lale 1'1'01. E. 4- CARTRAGE. By Prof. ALFRED A. FREEMAN. 1- CHURCH. 32. THE TUSCAll' REPU~CS. 5. ALEXANDER'S EMl'IRE. By Bv BtH.I.A Dur:F1', . Prof. J. P. MAltAFn. 33· POLAND. By W. It )IORFILL, 6. THE mOORS IJl' SPAIN. By M.A. STANLEY LANE-POOLE. 31- P ARTRIA. lly Prof. GEORGE 7. AlI'CIENT EGYPT. By Prof. HAWLINSON. GEORGE RAWLINSON. 35· AUSTRALIAN COMMON, 8. RUNGARY. By Prof. ARMINIC. WEALTH. By GREVILLB VAIUDRI(Y. J TREGARTHE~. 9. THE SARACENS. By ARTHUR 36. SPAIN. By H. E. WAlTS. GILMAN, M.A. 37. lAPAlI'. By DAVID MURRAY. 10. IRELAlI'D. By lhe Hall. EMILY Ph.D. LAWLESS. 38. SOUTH AFRICA. By GEORGB 11. CRALDEA. By ZENAiDB A. RAGOZIN. 39. vljI'Ml~Aty AI.ETHEA {VIE .. 12. THE GOTHS, By HElIRY BHAI>' 40. THE CRUSADES. By T. A. LEY. " AltCHER and C. L. ]{I)lGSFORO. 13. ASSYRIA. By ztNArDE A. RA· 41. VEDIC IJl'DIA.. By·Z. A. llA· GOZIN. GOZDl. 14. TURKEY. By STANLEY LASE· 4'. WEST INDIES and the SPAJl'ISH POOLE. MAIJl'. By JAMES RODWAY. IS. -

Matthias Corvinus and Charles the Bold1

Matthias Corvinus and Charles the Bold1 ATTILA BÁRÁNY • The paper investigates the diplomatic relations of Matthias Corvinus with the Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, focusing on the 1460s and ‘70s. It is trying to put new lights on a slightly neglected field of the Corvinian foreign policy, that is, Western European contacts. Apart from the sole effort of Jenő Horváth in the 1930s there have been no researches looking further behind the traditionally emphasized scope of Matthias’ diplomatic activity, that is, the Ottomans and the Habsburgs.2 I am to introduce a wider span of Matthias’ diplomacy. His concerns were not re- stricted to Central Europe but he was able to run a leading role in the European „grand policie”. The paper explores the political ties with the Duchy of Burgun- dy, with which Matthias wished to have Hungary involved in the anti-Habsburg, anti-Valois and pro-Burgundian „axis” of the contemporary European diplo- matic system. Matthias’ foreign policy is to be seen within the framework of the French-Burgundian antagonism, also in line with his Neapolitan stand: he faced the Venice-backed Valois-party, promoting René d’Anjou for the throne of Naples. Nevertheless, Matthias’s reason to enter the Burgundian league might have been that he hoped to get financial resources for the struggle against the Turks. First, I am going to oversee the relationship of Burgundy and Hungary in the framework of a parallel power constellation, and give an overview of the parties’ common allies and partners within the Holy Roman Empire. Both Burgundy and Hungary were seeking for allies within Germany – the houses of Wettin, Wittels- bach, both its Palatinate and Bavarian branches – against France, Emperor Fred- erick III and the Jagiellonians, which put them onto the same diplomatic track. -

Medieval Handgonnes Weapon

MEDIEVAL HANDGONNES The first black powder infantry weapons SEAN MC LACHLAN © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com weapon MEDIEVAL HANDGONNES SEAN McLACHLAN Series Editor Martin Pegler © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com First publishedin Great Britain in2010 by Osprey Publishing, Artist’s note Midland House, West Way, Botley, Oxford, OX2 0PH, UK Readers may care to note that theoriginal paintings from which 44-02 23rd Street, Suite 219, Long Island City, NY 11101, USA thecolour plates inthis bookwere prepared are available for private sale. All reproduction copyright whatsoever is retained E-mail: [email protected] bythePublishers. All enquiries should beaddressed to: ©2010 Osprey Publishing Ltd. www.gerryembleton.com All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose ThePublishers regret th at they can enter into no correspondence of private study, research,criti cism or review, as permitted under upon this matter. the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, no part of this publication may be reproduced, storedin a retrieval system, or Dedication transmittedin any form or by any means, electronic, electrical, For Almudena, my wife, and Julián, my son. chemical, mechanical, optical,photocopying, recording or Acknowledgements otherwise, without theprior wr itten permission of the copyright My research on thissubject was made possiblethrough the owner. Enquiries should beaddressed to thePublishers. advice andhelpofdozens of historians, archaeologists, museum A CIP catalogue record for this bookisavailablefromtheBritish -

The Swiss in the Swabian War of 1499: an Analysis of the Swiss Military at the End of the Fifteenth Century

Swiss American Historical Society Review Volume 56 Number 3 Article 4 11-2020 The Swiss in the Swabian War of 1499: An Analysis of the Swiss Military at the End of the Fifteenth Century Albert Winkler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review Part of the European History Commons, and the European Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Winkler, Albert (2020) "The Swiss in the Swabian War of 1499: An Analysis of the Swiss Military at the End of the Fifteenth Century," Swiss American Historical Society Review: Vol. 56 : No. 3 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review/vol56/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swiss American Historical Society Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Winkler: The Swiss in the Swabian War of 1499 The Swiss in the Swabian War of 1499: An Analysis of the Swiss Military at the End of the Fifteenth Century by Albert Winkler Introduction By the end of the fifteenth century, the states of the Swiss Con- federation had enjoyed almost complete autonomy from the neighbor- ing feudal powers for generations. During the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the states of the Swiss Confederation were beset by external threats to their security, independence, and existence. The largest sin- gle menace to Swiss independence was the Habsburg family who often controlled their lands according to monarchal authority and a social structure which kept their subject peoples as unfree serfs.