Negotiating Sovereignties with Jeff Lemire's Equinox

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada

Drawing on the Margins of History: English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada by Kevin Ziegler A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2013 © Kevin Ziegler 2013 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This study analyzes the techniques that Canadian comics life writers develop to construct personal histories. I examine a broad selection of texts including graphic autobiography, biography, memoir, and diary in order to argue that writers and readers can, through these graphic narratives, engage with an eclectic and eccentric understanding of Canadian historical subjects. Contemporary Canadian comics are important for Canadian literature and life writing because they acknowledge the importance of contemporary urban and marginal subcultures and function as representations of people who occasionally experience economic scarcity. I focus on stories of “ordinary” people because their stories have often been excluded from accounts of Canadian public life and cultural history. Following the example of Barbara Godard, Heather Murray, and Roxanne Rimstead, I re- evaluate Canadian literatures by considering the importance of marginal literary products. Canadian comics authors rarely construct narratives about representative figures standing in place of and speaking for a broad community; instead, they create what Murray calls “history with a human face . the face of the daily, the ordinary” (“Literary History as Microhistory” 411). -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Truth, Justice, and the Canadian Way: the War-Time Comics of Bell Features Publications Ivan Kocmarek Hamilton, Ontario

Truth, Justice, and the Canadian Way: The War-Time Comics of Bell Features Publications Ivan Kocmarek Hamilton, Ontario 148 What might be called the “First Age of Canadian Comics”1 began on a consum- mately Canadian political and historical foundation. Canada had entered the Second World War on September 10, 1939, nine days after Hitler invaded the Sudetenland and a week after England declared war on Germany. Just over a year after this, on December 6, 1940, William Lyon MacKenzie King led parliament in declaring the War Exchange Conservation Act (WECA) as a protectionist measure to bolster the Canadian dollar and the war economy in general. Among the paper products now labeled as restricted imports were pulp magazines and comic books.2 Those precious, four-colour, ten-cent treasure chests of American culture that had widened the eyes of youngsters from Prince Edward to Vancouver Islands immedi- ately disappeared from the corner newsstands. Within three months—indicia dates give March 1941, but these books were probably on the stands by mid-January— Anglo-American Publications in Toronto and Maple Leaf Publications in Vancouver opportunistically filled this vacuum by putting out the first issues of Robin Hood Comics and Better Comics, respectively. Of these two, the latter is widely considered by collectors to be the first true Canadian comic book becauseRobin Hood Comics Vol. 1 No. 1 seems to have been a tabloid-sized collection of reprints of daily strips from the Toronto Telegram written by Ted McCall and drawn by Charles Snelgrove. Still in Toronto, Adrian Dingle and the Kulbach twins combined forces to release the first issue of Triumph-Adventure Comics six months later (August 1941), and then publisher Cyril Bell and his artist employee Edmund T. -

Memorials of a Half-Century: a Machine-Readable Transcription

Library of Congress Memorials of a half-century 2194 War Department RECEIVED July 25, 1887, LIBRARY. MEMORIALS OF A HALF-CENTURY BY BELA HUBBARD “I have been a great feast, and stolen the sraps.” Love's Labor Lost.— SHAKES. “...various, that the mind Of desultory man, studious of change, And pleased with novelty, might be indulg'd.” The Task.— COWPER. WITH ILLUSTRATIONS NEW YORK & LONDON G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS The Knickerbocker Press 1887 copy 2 F566 .-87 copy 2 COPYRIGHT BY G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS 1887 By transfer OCT 9 1915 Press of G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS New York “The notes of a single observer, even in a limited district, describing accurately its features, civil, natural and social, are of more interests, and often of more value, than the grander view and boarder generalizations of history. “In a country whose character and circumstances are constantly changing, the little facts and incidents, which are the life history, soon pass from the minds of the present generation.”— Anon v PREFACE. War Department LIBRARY. Memorials of a half-century http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbum.21049 Library of Congress The writer came to Michigan, a youth, in the spring of 1835, and settled in the town of Springwells, two miles from the western limits of Detroit, then a city of less than 500 inhabitants. On or near the spot of his first abode, upon the banks of our noble river, he has dwelt for half a century, and until the spreading city has absorbed the intervening farms. Even a few years ago his present residence was so completely in the country, that the familiar rural sights and sounds were but little banished. -

Black Label/Hill House

BLACK LABEL/HILL HOUSE SUMMER/FALL 2020 CATALOG Summer & Fall 2020 From captivating and complex superhero titles to terrifying horror tales, DC Black Label is committed to telling mature and timeless stand-alone stories. These collections for Summer/Fall 2020 are perfect for everyday readers looking for accessible and distinctive jumping-on points. First, the White Knight saga continues! Sean Murphy returns as writer and artist on Batman: Curse of the White Knight, the sequel to his blockbuster Batman: White Knight. As Batman prepares to reveal his identity, the Joker and Azrael team up to wield a shocking piece of lost history that will corrupt Batman’s legacy and shake Gotham to its foundation. In Harley Quinn & The Birds of Prey, Amanda Conner and Jimmy Palmiotti return to have some fun with the character they revolutionized; and Jeff Lemire and Andrea Sorrentino explore the crooked corridors of Joker’s mind in Joker: Killer Smile. DC Black Label is passionate about showcasing the most amazing artists in the industry. Two more books that feature eye-popping art were also year-end hits in the direct market: the outstanding Dark Knight Returns: The Golden Child, written by Frank Miller and illustrated by Rafael Grampa, and the stunning Wonder Woman: Dead Earth, written and illustrated by the monstrously talented Daniel Warren Johnson. Then, New York Times bestselling writer Geoff Johns and Jason Fabok team up for the long-awaited Batman: Three Jokers. 30 years after The Killing Joke changed comics forever, this story re-examines the myth of the Joker and explores the depths of his ongoing battle with Batman. -

Wolverine Logan, of the X-Men and the New Avengers

Religious Affiliation of Comics Book Characters The Religious Affiliation of Comic Book Character Wolverine Logan, of the X-Men and the New Avengers http://www.adherents.com/lit/comics/Wolverine.html Wolverine is the code name of the Marvel Comics character who was long known simply as "Logan." (Long after his introduction, the character's real name was revealed to be "James Howlett.") Although originally a relatively minor character introduced in The Incredible Hulk #180-181 (October - November, 1974), the character eventually became Marvel's second-most popular character (after Spider-Man). Wolverine was for many years one of Marvel's most mysterious characters, as he had no memory of his earlier life Above: Logan and the origins of his distinctive (Wolverine) prays at a Adamantium skeleton and claws. Like Shinto temple in Kyoto, much about the character, his religious Japan. affiliation is uncertain. It is clear that [Source: Wolverine: Wolverine was raised in a devoutly Soultaker, issue #2 (May Christian home in Alberta, Canada. His 2005), page 6. Written by family appears to have been Protestant, Akira Yoshida, illustrated although this is not certain. At least by Shin "Jason" Nagasawa; reprinted in into his teen years, Wolverine had a Wolverine: Soultaker, strong belief in God and was a Marvel Entertainment prayerful person who strived to live by Group: New York City specific Christian ethics and moral (2005).] teachings. Above: Although Logan (Wolverine) is not a Catholic, and Over the many decades since he was a Nightcrawler (Kurt Wagner) is not really a priest, Logan child and youth in 19th Century nevertheless was so troubled by Alberta, Wolverine's character has his recent actions that he changed significantly. -

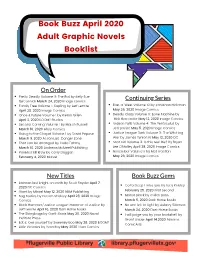

April Book Buzz AGN Booklist

Book Buzz April 2020 Adult Graphic Novels Booklist On Order Pretty Deadly Volume 3: The Rat by Kelly Sue Continuing Series DeConnick March 24, 2020 Image comics Family Tree Volume 1: Sapling by Jeff Lemire East of West Volume 10 by Jonathan Hickman April 28, 2020 Image Comics May 26, 2020 Image Comics Once & Future Volume 1 by Kieron Gillen Deadly Class Volume 9: Bone Machine by April 2, 2020 BOOM! Studios Rick Remender May 12, 2020 Image Comics Second Coming Volume 1 by March Russell Gideon Falls Volume 4: The Pentoculus by March 10, 2020 Ahoy Comics Jeff Lemire May 5, 2020 Image Comics Going to the Chapel Volume 1 by David Pepose Justice League Dark Volume 3: The Witching March 3, 2020 Action Lab-Danger Zone War by James Tynion IV May 12, 2020 DC That can be arranged by Huda Fahmy Snot Girl Volume 3: Is this real life? By Bryan March 10, 2020 Andrews McMeel Publishing Lee O’Malley April 28, 2020 Image Comics Punisher kill krew by Gerry Duggan November Volume II by Mat Fraction February 4, 2020 Marvel May 26, 2020 Image Comics New Titles Book Buzz Gems Batman last knight on earth by Scott Snyder April 7, Go to Sleep I miss you by Lucy Knisley 2020 DC Comics Giant by Mikael May 12, 2020 NBM Publishing February 25, 2020 First Second Bog Bodies by Declan Shalvey April 28, 2020 Image Manor Black by Cullen Bunn Comics March 5, 2020 Dark Horse Books Black Hammer/Justice League: Hammer of Justice by No one left to fight by Aubrey Sitterson Jeff Lemire April 16, 2020 Dark Horse Books March 24, 2020 Dark Horse Books The Stringbags by Garth Ennis May 20, 2020 Naval I will judge you by your bookshelf by Institute Press Grant Snider April 14.2020 Abrams Eat & love yourself by Sweeney Boo May 28, 2020 BOOM! ComicArts Little Victories by Yvon Roy May 2020 Titan Comics BOOK BUZZ ADULT NON-FICTION TITLES N o b o d y W i l l T e l l Y o u T h i s B u t M e b y B e s s K a l b M a r c h 1 7 , 2 0 2 0 s y W o w , N o T h a n k Y o u b y S a m a n t h a I r b y M a r c h 3 1 , 2 0 2 0 a s s H e r e F o r I t : O r , H o w t o S a v e Y o u r S o u l i n A m e r i c a b y R . -

The Florida Historical Quarterly

COVER The Gainesville Graded and High School, completed in 1900, contained twelve classrooms, a principal’s office, and an auditorium. Located on East University Avenue, it was later named in honor of Confederate General Edmund Kirby Smith. Photograph from the postcard collection of Dr. Mark V. Barrow, Gainesville. The Historical Quarterly Volume LXVIII, Number April 1990 THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY COPYRIGHT 1990 by the Florida Historical Society, Tampa, Florida. The Florida Historical Quarterly (ISSN 0015-4113) is published quarterly by the Florida Historical Society, Uni- versity of South Florida, Tampa, FL 33620, and is printed by E. O. Painter Printing Co., DeLeon Springs, Florida. Second-class postage paid at Tampa and DeLeon Springs, Florida. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to the Florida Historical Society, P. O. Box 290197, Tampa, FL 33687. THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY Samuel Proctor, Editor Everett W. Caudle, Editorial Assistant EDITORIAL. ADVISORY BOARD David R. Colburn University of Florida Herbert J. Doherty University of Florida Michael V. Gannon University of Florida John K. Mahon University of Florida (Emeritus) Jerrell H. Shofner University of Central Florida Charlton W. Tebeau University of Miami (Emeritus) Correspondence concerning contributions, books for review, and all editorial matters should be addressed to the Editor, Florida Historical Quarterly, Box 14045, University Station, Gainesville, Florida 32604-2045. The Quarterly is interested in articles and documents pertaining to the history of Florida. Sources, style, footnote form, original- ity of material and interpretation, clarity of thought, and in- terest of readers are considered. All copy, including footnotes, should be double-spaced. Footnotes are to be numbered con- secutively in the text and assembled at the end of the article. -

2News Summer 05 Catalog

X-Men, Alpha Flight, and all related characters TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 0 8 THIS ISSUE: INTERNATIONAL THIS HEROES! ISSUE: INTERNATIONAL No.83 September 2015 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 featuring an exclusive interview with cover artists Steve Fastner and Rich Larson Alpha Flight • New X-Men • Global Guardians • Captain Canuck • JLI & more! Volume 1, Number 83 September 2015 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTISTS Steve Fastner and Rich Larson COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Jack Abramowitz Martin Pasko Howard Bender Carl Potts Jonathan R. Brown Bob Rozakis FLASHBACK: International X-Men . 2 Rebecca Busselle Samuel Savage The global evolution of Marvel’s mighty mutants ByrneRobotics.com Alex Saviuk Dewey Cassell Jason Shayer FLASHBACK: Exploding from the Pages of X-Men: Alpha Flight . 13 Chris Claremont Craig Shutt John Byrne’s not-quite-a team from the Great White North Mike Collins David Smith J. M. DeMatteis Steve Stiles BACKSTAGE PASS: The Captain and the Controversy . 24 Leopoldo Duranona Dan Tandarich How a moral panic in the UK jeopardized the 1976 launch of Captain Britain Scott Edelman Roy Thomas WHAT THE--?!: Spider-Man: The UK Adventures . 29 Raimon Fonseca Fred Van Lente Ramona Fradon Len Wein Even you Spidey know-it-alls may never have read these stories! Keith Giffen Jay Williams BACKSTAGE PASS: Origins of Marvel UK: Not Just Your Father’s Reprints. 37 Steve Goble Keith Williams Repurposing Marvel Comics classics for a new audience Grand Comics Database Dedicated with ART GALLERY: López Espí Marvel Art Gallery . -

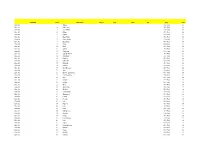

Set Name Card Description Sketch Auto

Set Name Card Description Sketch Auto Mem #'d Odds Point Base Set 1 Angela 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 2 Anti-Venom 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 3 Doc Samson 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 4 Attuma 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 5 Bedlam 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 6 Black Knight 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 7 Black Panther 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 8 Black Swan 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 9 Blade 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 10 Blink 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 11 Callisto 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 12 Cannonball 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 13 Captain Universe 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 14 Challenger 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 15 Punisher 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 16 Dark Beast 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 17 Darkhawk 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 18 Collector 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 19 Devil Dinosaur 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 20 Ares 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 21 Ego The Living Planet 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 22 Elsa Bloodstone 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 23 Eros 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 24 Fantomex 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 25 Firestar 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 26 Ghost 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 27 Ghost Rider 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 28 Gladiator 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 29 Goblin Knight 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 30 Grandmaster 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 31 Hazmat 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 32 Hercules 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 33 Hulk 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 34 Hyperion 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 35 Ikari 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 36 Ikaris 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 37 In-Betweener 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 38 Khonshu 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 39 Korvus 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 40 Lady Bullseye 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 41 Lash 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 42 Legion 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 43 Living Lightning 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 44 Maestro 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 45 Magus 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 46 Malekith 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 47 Manifold 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 48 Master Mold 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 49 Metalhead 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 50 M.O.D.O.K. -

Comunicado De Novedades Marzo/2015 a La Venta El 25/02/15

COMUNICADO DE NOVEDADES MARZO/2015 A LA VENTA EL 25/02/15 WWW.ECCEDICIONES.COM WWW.LIBRERIAS.ECCEDICIONES.COM [email protected] [email protected] SÍGUENOS EN www.facebook.com/ECCEdiciones twitter.com/eccediciones www.youtube.com/user/CanalECCEdiciones www.instagram.com/eccediciones Google+ MARZO ecididos a mantener el impulso con el que comenzamos 2015 y empeñados en despedir el primer trimestre del año con todos los honores, hemos confeccionado una tanda de novedades que hará de marzo un mes muy esperado. No solo por la inminencia de la primavera, sino también por la publicación de numerosos tebeos que, estamos convenci- Ddos, suscitarán el interés de nuestros lectores. Así, el nuevo Universo DC presentará novedades de alcance, buena parte de ellas relacionadas con El fin del mañana. Editada en forma de tomos mensuales, la saga ejercerá una notable influencia en el resto de colecciones de la editorial, tal y como se podrá apreciar en los especiales agrupados en tomos temáticos dedicados a Batman, Superman, Liga de la Justicia y Green Lantern. Precisamente, la franquicia que gira en torno al cuerpo policial intergaláctico afrontará un ajetreado período marcado por Divinidad: crossover que durante los próximos meses sumirá a los portadores del anillo y a los Nuevos Dioses en una saga que publicaremos en la serie mensual Green Lantern. ¿Y qué decir de Wonder Woman? La colección protagonizada por la amazona despedirá una de sus más brillantes etapas, mezcla de aventura, intriga, superhéroes y mitología. Nos referimos a la firmada porBrian Azzarello y Cliff Chiang, que cederán el testigo a David y Meredith Finch, cuya estancia en la serie comenzará en julio. -

Download Justice League Dark Vol. 3: the Death of Magic (The New 52) PDF

Download: Justice League Dark Vol. 3: The Death of Magic (The New 52) PDF Free [249.Book] Download Justice League Dark Vol. 3: The Death of Magic (The New 52) PDF By Jeff Lemire Justice League Dark Vol. 3: The Death of Magic (The New 52) you can download free book and read Justice League Dark Vol. 3: The Death of Magic (The New 52) for free here. Do you want to search free download Justice League Dark Vol. 3: The Death of Magic (The New 52) or free read online? If yes you visit a website that really true. If you want to download this ebook, i provide downloads as a pdf, kindle, word, txt, ppt, rar and zip. Download pdf #Justice League Dark Vol. 3: The Death of Magic (The New 52) | #97497 in Books | 2014-02-04 | 2014-02-04 | Original language: English | PDF # 1 | 10.10 x .30 x 6.70l, .74 | File type: PDF | 192 pages | |2 of 2 people found the following review helpful.| Jeff Lemire | By Leah |Collects JLD: #14-21 This volume has some many fun things going on. The team ends up in another dimension where mages are hunted down and killed on sight by technologically OP armies. The best part? The new dimension affects the team in different ways. Xanadu is old and frail, Orchid is a savage monster, and Constantine compulsively tells the t | About the Author | Award-winning Canadian cartoonist Jeff Lemire is the creator of the acclaimed monthly comic book series SWEET TOOTH published by DC/Vertigo and the award winning graphic novel Essex County published by Top Shelf.