Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy (CEDS)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

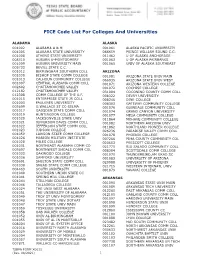

FICE Code List for Colleges and Universities (X0011)

FICE Code List For Colleges And Universities ALABAMA ALASKA 001002 ALABAMA A & M 001061 ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY 001005 ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY 066659 PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND C.C. 001008 ATHENS STATE UNIVERSITY 011462 U OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE 008310 AUBURN U-MONTGOMERY 001063 U OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS 001009 AUBURN UNIVERSITY MAIN 001065 UNIV OF ALASKA SOUTHEAST 005733 BEVILL STATE C.C. 001012 BIRMINGHAM SOUTHERN COLL ARIZONA 001030 BISHOP STATE COMM COLLEGE 001081 ARIZONA STATE UNIV MAIN 001013 CALHOUN COMMUNITY COLLEGE 066935 ARIZONA STATE UNIV WEST 001007 CENTRAL ALABAMA COMM COLL 001071 ARIZONA WESTERN COLLEGE 002602 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 001072 COCHISE COLLEGE 012182 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 031004 COCONINO COUNTY COMM COLL 012308 COMM COLLEGE OF THE A.F. 008322 DEVRY UNIVERSITY 001015 ENTERPRISE STATE JR COLL 008246 DINE COLLEGE 001003 FAULKNER UNIVERSITY 008303 GATEWAY COMMUNITY COLLEGE 005699 G.WALLACE ST CC-SELMA 001076 GLENDALE COMMUNITY COLL 001017 GADSDEN STATE COMM COLL 001074 GRAND CANYON UNIVERSITY 001019 HUNTINGDON COLLEGE 001077 MESA COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001020 JACKSONVILLE STATE UNIV 011864 MOHAVE COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001021 JEFFERSON DAVIS COMM COLL 001082 NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIV 001022 JEFFERSON STATE COMM COLL 011862 NORTHLAND PIONEER COLLEGE 001023 JUDSON COLLEGE 026236 PARADISE VALLEY COMM COLL 001059 LAWSON STATE COMM COLLEGE 001078 PHOENIX COLLEGE 001026 MARION MILITARY INSTITUTE 007266 PIMA COUNTY COMMUNITY COL 001028 MILES COLLEGE 020653 PRESCOTT COLLEGE 001031 NORTHEAST ALABAMA COMM CO 021775 RIO SALADO COMMUNITY COLL 005697 NORTHWEST -

North Central Alabama Region Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy Table of Contents North Central Alabama Regional Council of Governments

COMPREHENSIVE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY North Central Alabama Region Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy Table of Contents North Central Alabama Regional Council of Governments CEDS STRATEGY COMMITTEE 3 MISSION, VISION, & GOALS 4 INTRODUCTION 5 1 SUMMARY BACKGROUND 8 2 SWOT ANALYSIS & ASSET BASED APPROACH 30 3 STRATEGIC DIRECTION & ACTION PLAN 32 4 EVALUATION FRAMEWORK 37 5 ECONOMIC RESILIENCE 38 APPENDIX 45 CEDS STRATEGY COMMITTEE The CEDS Strategy Committee is comprised of various stakeholders representing Suzanne Harbin (Kristi Barnett) Wallace State Community College economic development organizations, Joseph Burchfield Tennessee Valley Authority chambers of commerce, tourism, Danielle Gibson Hartselle Chamber of Commerce entrepreneurs, education, workforce Cherrie Haney Cullman County Economic Development development, utilities, and local business Jason Houston Lawrence County Chamber of Commerce owners in the Region. The purpose of John Joseph IV Decatur Corridor Development, Inc. the committee is to prepare input and Dale Greer (Stanley Kennedy) Cullman Economic Development Agency information on the future direction of the Brooks Kracke North Alabama Industrial Development Association Region and to offer guidance on potential Tim Lovelace NARCOG Small Business Fund Loan Committee future initiatives of NARCOG. Jeremy Nails Morgan County Economic Development Agency Dr. Jim Payne Calhoun Community College Jesslyn Reeves Decatur City Schools Foundation Tami Reist North Alabama Mountain Lakes Tourist Association John Seymour Decatur-Morgan County Chamber of Commerce Leah Bolin (Ben Smith) Cullman Area Chamber of Commerce Tony Stockton Lawrence County Industrial Development Board Larry Waye Decatur-Morgan County Entrepreneurial Center & NARCOG Board Member 3 MISSION, VISION AND GOALS MISSION Dedicated to improving the quality of life for the citizens of Cullman County, Lawrence County, and Morgan County. -

0708 Carbon Sequestration and Enhanced Coalbed Methane Recovery Potential of the Cahaba and Coosa Coalfields in the Southern

0708 Carbon Sequestration and Enhanced Coalbed Methane Recovery Potential of the Cahaba and Coosa Coalfields in the Southern Appalachian Thrust Belt M. R. McIntyre and J. C. Pashin Geological Survey of Alabama, P.O. Box 869999, Tuscaloosa, AL 35486 ABSTRACT Pennsylvanian coal-bearing strata in the Pottsville Formation of the Black Warrior basin in Alabama have been recognized as having significant potential for carbon sequestration and enhanced coalbed methane recovery, and additional potential may exist in Pottsville strata in smaller coalfields within the Appalachian thrust belt in Alabama. The Coosa and Cahaba coalfields contain as much as 8,500 feet of Pennsylvanian-age coal-bearing strata, and economic coal and coalbed methane resources are distributed among multiple coal seams ranging in thickness from 1 to 12 feet. In the Coosa coalfield, 15 named coal beds are concentrated in the upper 1,500 feet of the Pottsville Formation. In the Cahaba coalfield, by comparison, coal is distributed through 20 coal zones that span nearly the complete Pottsville section. Limited coalbed methane development has taken place in the Coosa coalfield, but proximity of a major Portland cement plant to the part of the coalfield with the greatest coalbed methane potential may present an attractive opportunity for carbon sequestration and enhanced coalbed methane recovery. In the Coosa coalfield, coalbed methane and carbon sequestration potential are restricted to the Coal City basin, where data from 10 coalbed methane wells and 24 exploratory core holes are available for assessment. Because of its relatively small area, the Coal City basin offers limited potential for carbon sequestration, although the potential for coalbed methane development remains significant. -

THE WAR of 1812 in CLAY COUNTY, ALABAMA by Don C. East

THE WAR OF 1812 IN CLAY COUNTY, ALABAMA By Don C. East BACKGROUND The War of 1812 is often referred to as the “Forgotten War.” This conflict was overshadowed by the grand scale of the American Revolutionary War before it and the American Civil War afterwards. We Americans fought two wars with England: the American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. Put simply, the first of these was a war for our political freedom, while the second was a war for our economic freedom. However, it was a bit more complex than that. In 1812, the British were still smarting from the defeat of their forces and the loss of their colonies to the upstart Americans. Beyond that, the major causes of the war of 1812 were the illegal impressments of our ships’ crewmen on the high seas by the British Navy, Great Britain’s interference with our trade and other trade issues, and the British incitement of the Native Americans to hostilities against the Americans along the western and southeast American frontiers. Another, often overlooked cause of this war was it provided America a timely excuse to eliminate American Indian tribes on their frontiers so that further westward expansion could occur. This was especially true in the case of the Creek Nation in Alabama so that expansion of the American colonies/states could move westward into the Mississippi Territories in the wake of the elimination of the French influence there with the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, and the Spanish influence, with the Pinckney Treaty of 1796. Now the British and the Creek Nation were the only ones standing in the way of America’s destiny of moving the country westward into the Mississippi Territories. -

Community Foundation of Northeast Alabama

Community Foundation of Northeast Alabama 2015 - Annual Report Our Vision The Foundation will leverage and use its philanthropic resources to foster a region where residents have access Mission Statement to medical care, where quality education is supported and To wisely assess needs and channel donor resources valued and where people respect to maximize community well-being. and care for one another. Our Region Table of Contents Thomas C. Turner Memorial Fund ------------------------------------------- 1 Grants ------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 2 Sight Savers America's KidCheck Plus Program --------------------------- 3 City of Anniston Competitive Fund ----------------------------------------- 4 Marianna Greene Henry Special Equestrian Program ------------------ 5 Standards for Excellence® ------------------------------------------------------ 6 List of Funds ---------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 New Funds ----------------------------------------------------------------------- 12 Juliette P. Doster Award ------------------------------------------------------- 13 Scholarship Highlights --------------------------------------------------------- 14 Memorials ----------------------------------------------------------------------- 16 Honorariums --------------------------------------------------------------------- 17 Our Values Anvil Society -------------------------------------------------------------------- 18 Statement of Financial Position --------------------------------------------- -

Suggested Study Materials for the Alabama Land Surveying History & Law

ALLS Exam Blueprint Standards of Professional Practice - 13 Questions ASPLS Standards of Practice (SOP) AL Licensure Law & Administrative Code Administrative Code of Ethics Boundary Control & Legal Principles - 11 Questions Research & Reconnaissance Monuments, Corners & Order of Calls Acquiescence, Practical Location, Estoppel, Repose Parol Agreement Junior/Senior Rights Adverse Possession & Prescription Page 2 ALLS Exam Blueprint Survey Systems - 9 Questions History in Alabama: Pure History, Re-establish & Miscellaneous Subdivisions Metes & Bounds State Plane Coordinate System Statutes & Regulations - 8 Questions On-Site Sewage Disposal Platting FEMA Flood Insurance Cemetaries, Right-of-Entry & Eminent Domain Statues of Limitations Conveyances & Title - 8 Questions Deeds, Descriptions & Rules of Construction Easements & Rights-of-way Recording Statutes Rules of Evidence Page 3 ALLS Exam Blueprint Case Law - 6 Questions Standard of Care (Paragon Engineering vs. Rhodes) PLSS (First Beat Entertainment vs. EEC) Evidence (Billingsly vs. Bates) Monuments (Jackson vs. Strickland) Adverse Possession (Strickland vs. Markos) Prescriptive Easements (Hanks vs. Spann) Easements (Chatham vs. Blount County) Water Boundaries (Wehby vs. Turpin) Water Boundaries (Spottswood vs. Reimer) Recording Statutes (Jefferson County vs. Mosely) Water Boundaries - 5 Questions Definitions & Terms Riparian Rights Navigability Suggested Study Materials for the Alabama Land Surveying History & Law Study Material How to get the Materials Code of Alabama 1975 • Title 34 -

The Indians of East Alabama and the Place Names They Left Behind

THE INDIANS OF EAST ALABAMA AND THE PLACE NAMES THEY LEFT BEHIND BY DON C. EAST INTRODUCTION When new folks move to Lake Wedowee, some of the first questions they ask are: “what is the meaning of names like Wedowee and Hajohatchee?” and “what Indian languages do the names Wehadkee and Fixico come from?” Many of us locals have been asked many times “how do you pronounce the name of (put in your own local town bearing an Indian name) town?” All of us have heard questions like these before, probably many times. It turns out that there is a good reason we east Alabama natives have heard such questions more often than the residents of other areas in Alabama. Of the total of 231 Indian place names listed for the state of Alabama in a modern publication, 135 of them are found in 18 counties of east Alabama. Put in other words, 58.4% of Alabama’s Indian place names are concentrated in only 26.8% of it’s counties! We indeed live in a region that is rich with American Indian history. In fact, the boundaries of the last lands assigned to the large and powerful Creek Indian tribe by the treaty at Fort Jackson after the Red Stick War of 1813-14, were almost identical to the borders of what is known as the "Sunrise Region" in east central Alabama. These Indian names are relics, like the flint arrowheads and other artifacts we often find in our area. These names are traces of past peoples and their cultures; people discovered by foreign explorers, infiltrated by early American traders and settlers, and eventually forcefully moved from their lands. -

Books Or Pamphlets Written About Clay County, Alabama Compiled by Don C

Books or pamphlets written about Clay County, Alabama Compiled by Don C. East, 2009 Few words of description and definition have been put in print about Clay County since its beginnings in 1866. The following list of published material contains the thoughts of a few native countians and a couple of outsiders regarding this mountainous east central Alabama county and its people. Many of these sources are now out of print and difficult to find. In many cases, there is only a single copy known to be available to the public at each of the two county libraries in Ashland and Lineville. The sources are in chronological order of publishing or printing. Any suggested additions to this list of books on Clay County should be forwarded to this Clay County Chamber of Commerce web site at [email protected] or Mary patchunka- smith at [email protected]. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 1. Shinbone Valley, The Stricklands and the Elders.. By Vista Strickland. Self-published pamphlet. Circa 1920s. This pamphlet cast some light on a secluded section in the mountains in north Clay County. Ms. Strickland’s remembrances go back to the earliest pioneer settlers in the area. This source is out of print. Copies are held at the Ashland and Lineville public libraries. 2. Horse and Buggy Days on Hatchet Creek. By Mitchell B. Garrett. The University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa and Auburn. 1957. This book describes life along Hatchet Creek in western Clay County as it tells the story of a rural Alabama boyhood in the 1890s. Limited used copies of this book can be sometimes found on the web and copies are held by the Ashland and Lineville public libraries. -

Monthly Economic Data Summary South Region

Monthly Economic Data Summary South Region September 2021 Regions Bank Economics Division Richard F. Moody Greg McAtee Chief Economist Senior Economist Nonfarm % from Economics Division Nonfarm Employment, ths % change year ago Employment, peak, May-21 Jun-21 Jul-21 May-21 Jun-21 Jul-21 Q1 2020 peak (ths) Jul-21 CENTRAL ALABAMA: Auburn-Opelika, AL 66.000 66.400 66.900 11.68 8.50 6.87 67.800 -1.33 Dothan, AL 58.800 59.300 59.900 5.19 4.40 4.54 60.600 -1.16 Montgomery, AL 169.300 170.000 170.200 5.29 3.91 2.53 178.000 -4.38 NORTH ALABAMA: Decatur, AL 57.000 57.100 57.300 4.59 3.44 2.87 58.300 -1.72 Florence-Muscle Shoals, AL 55.300 55.200 54.800 7.80 3.18 1.11 57.500 -4.70 Huntsville, AL 248.600 249.400 249.800 8.13 6.22 4.87 249.400 0.16 NORTH-CENTRAL ALABAMA: Anniston-Oxford-Jacksonville, AL 45.900 45.700 45.800 7.49 3.39 2.00 47.700 -3.98 Birmingham-Hoover, AL 531.100 535.000 538.200 6.86 5.98 5.53 548.700 -1.91 Gadsden, AL 33.900 34.000 33.900 9.35 4.94 3.35 37.000 -8.38 Tuscaloosa, AL 105.600 105.900 105.900 9.09 5.37 3.42 114.300 -7.35 SOUTH ALABAMA/FLORIDA PANHANDLE: Crestview-Fort Walton Beach-Destin, FL 117.100 117.400 117.700 7.04 3.35 3.34 119.700 -1.67 Daphne-Fairhope-Foley AL 80.000 80.800 81.800 11.58 8.75 7.63 81.400 0.49 Mobile, AL 179.300 180.000 180.200 5.22 3.87 3.15 187.200 -3.74 Panama City, FL 79.900 80.500 80.200 7.39 5.09 3.48 81.900 -2.08 Pensacola-Ferry Pass-Brent, FL 185.600 186.300 186.900 6.06 3.27 3.26 188.700 -0.95 SOUTH LOUISIANA: Baton Rouge, LA 385.800 384.100 387.100 6.57 3.95 3.56 409.200 -5.40 Houma-Thibodaux, LA 82.700 82.700 82.600 5.48 4.68 4.03 87.400 -5.49 Lafayette, LA 190.800 192.300 193.100 4.21 3.95 3.32 206.200 -6.35 New Orleans-Metairie, LA 523.400 526.300 530.000 7.41 4.09 3.50 592.600 -10.56 SOUTH MISSISSIPPI: Gulfport-Biloxi-Pascagoula, MS 152.900 153.900 154.900 13.34 6.36 4.59 158.500 -2.27 Hattiesburg, MS 64.600 64.800 65.600 7.67 4.68 4.96 65.300 0.46 Jackson, MS 266.000 268.400 270.900 6.87 3.91 2.89 279.300 -3.01 U.S. -

Factsheet1 CAVHCS.Pdf

Central Alabama Veterans Health Care System “Proudly serving the Veterans” Montgomery Campus Tuskegee Campus 215 Perry Hill Road - Montgomery, AL 36109 2400 Hospital Road - Tuskegee, AL 36083 (334) 272-4670 (334) 727-0550 The Central Alabama Veterans Health Care System (CAVHCS) includes the Montgomery and Tuskegee VA Medical Centers, as well as community based outpatient clinics at Ft. Rucker (Wiregrass Clinic), two facilities in Dothan, Alabama, and one in Columbus, Georgia. These six sites serve 140,000 veterans in 43 counties in the central and southeastern portions of Alabama and western Georgia. CAVHCS' mission is to provide excellent services to veterans across the continuum of health care. Our two largest facilities, the Montgomery and Tuskegee facilities are about 40 miles apart and offer employees a remarkable array of choices in the way of housing, shopping, educational opportunities, and recreation. CAVHCS has affiliations with 24 schools, including Morehouse School of Medicine, Alabama State University, Auburn University, the University of Alabama and Tuskegee University. CAVHCS is authorized 143 hospital beds, 160 Nursing Home Care Unit beds, and 43 Homeless Domiciliary beds. CAVHCS' vision is to be the preferred veterans' health care system for every stakeholder. In moving toward achieving this vision, CAVHCS will become a preferred health care provider for eligible veterans and other customers, and will be viewed as an employer of choice by staff, and be an integral member of the VA Southeast Network (VISN 7). In addition to providing comprehensive care for veterans residing in its catchment area, CAVHCS will position itself as a Network resource for geriatrics and extended care, rehabilitation and mental health services. -

Central to YOUR SUCCESS!

Central Alabama Community College Alexander City ● Childersburg ● Prattville ● Talladega www.cacc.edu Central to YOUR SUCCESS! EQUAL OPPORTUNITY IN EDUCATION AND EMPLOYMENT It is the official policy of the Alabama Community College System and Central Alabama Community College that no person on the basis of race, color, disability, sex, religion, creed, national origin, age, or other classification protected by law be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subject to discrimination under any program, activity, or employment. Furthermore, no qualified individual with a disability shall, on the basis of disability, be subject to discrimination in employment or in connection with any service, program, or activity conducted by the College. Central Alabama Community College complies with the non-discriminatory regulations under Title VI and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964; the Age Discrimination in Employment Act, Title IX Education Amendments of 1972; and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (as amended), the Vietnam Era Veterans Readjustment Assistance Act, the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (as amended), the Equal Pay Act, and the Pregnancy Discrimination Act. Student inquiries concerning reasonable accommodations may be directed to the ADA Coordinator in the Student Services Office(s) at each location. Complaint and grievance procedure forms are available in the Student Services Office. Students who wish to make a complaint regarding discriminatory conduct or retaliation should contact Dr. Sherri Taylor, Title IX Coordinator for student issues. For additional information on Title IX complaints, please refer to the Central Alabama Community College Student Handbook. Employee inquiries concerning reasonable accommodations may be directed to the Tina Shaw, Executive Human Resources Director, in the Human Resources Office. -

Oxford Reference

Oxford Reference October 2018 Client Name Searches Alabama A&M University 5 Alabama School of the Deaf and Blind 1 Alabama State University Library 2 Alabama Virtual Library 660 Alexander City Board of Education 2 Andalusia City Board of Education 16 Arab City Board of Education 1 Athens State University 30 Auburn City Board of Education 3 Auburn University 75 Auburn University Montgomery Library 35 Baldwin County Board of Education 24 Bevill State Community College 5 Birmingham City Board of Education 1 Birmingham Public Library 55 Birmingham Southern College 1 Blount County Board of Education 5 Central Alabama Community College 10 Central Alabama Community College - Childersburg 10 Chattahoochee Valley Community College 9 Clarke County Board of Education 2 Coastal Alabama Community College 6 Colbert County Board of Education 9 Covington County Board of Education 18 Cullman County Board of Education 6 Dallas County Board of Education 3 DeKalb County Board of Education 3 Enterprise City Board of Education 95 Enterprise-Ozark Community College 1 Enterprise-Ozark Community College (Aviation Campus) 1 Faulkner University 15 Fort Payne City Board of Education 1 Franklin County Board of Education 17 Gadsden City Board of Education 1 Geneva County Board of Education 1 George C. Wallace Community College (Dothan - Main) 1 Hale County Board of Education 2 Homewood City Board of Education 3 Hoover City Board of Education 5 Huntsville City Board of Education 7 J. F. Drake State Technical College 2 Jacksonville State University 28 James H. Faulkner State Community College 2 Jefferson County Board of Education 1 Jefferson County Library Cooperative 38 Jefferson Davis Community College 4 Jefferson State Community College 12 Jefferson State Community College - Shelby Campus 12 John C.