Tim Warfield, Eye of the Beholder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyrus Chestnut

Cyrus Chestnut Born on January 17, 1963, in Baltimore, MD; son of McDonald (a retired post office employee and church organist) and Flossie (a city social services worker and church choir director) Soulful jazz pianist Cyrus Chestnut might just be proof positive of the impact that music has on babies in the womb. Either that, or a life in music was simply in his blood. Chestnut's father, a postal employee and the son of a church minister, was the official organist for the local church in Baltimore, Maryland, where Chestnut grew up. Young Cyrus's home was filled with the sounds of the gospel music that his church-going parents played in their home, along with jazz records by artists such as Thelonius Monk and Jimmy Smith. Chestnut has said that the roots of his love of music began there, and to this day, Chestnut's ties to the gospel church remain constant. "Growing up, gospel music was what I heard in the house," Chestnut told Down Beat magazine. As a boy Chestnut reached for the piano keys before he could walk, so his father began teaching the earnest three-year-old to play the piano. One of the first songs young Cyrus learned was "Jesus Loves Me." Before long, seven-year-old Cyrus was playing piano in the family church, and by age nine he was promoted to church pianist at Mt. Calvary Star Baptist Church in Baltimore, Maryland. Chestnut, who became known for his improvisational skills and unique jazz-gospel and bop style, has credited his abilities to those formative years when he played at church. -

October 8, 2018 Jazz Album Chart

Jazz Album Chart October 8, 2018 TW LW 2W Peak Artist Title Label TW LW Move Weeks Reports Adds Yellowjackets 1 1 4 1 Raising Our Voice Mack Avenue 272 272 0 4 46 2 2 weeks at No. 1 2 2 16 2 Count Basie Orchestra All About That Basie Concord Jazz 266 242 24 3 48 5 3 4 9 3 Bob James Espresso Evolution Music 252 240 12 4 45 4 4 5 2 2 Karrin Allyson Some of That Sunshine kasrecords 250 239 11 8 52 1 5 3 1 1 Steve Turre The Very Thought of You Smoke Sessions 239 241 -2 6 50 1 6 7 41 6 Cécile McLorin Salvant The Window Mack Avenue 233 222 11 3 47 3 7 7 20 7 Christian Sands Facing Dragons Mack Avenue 231 222 9 3 51 6 Stefon Harris & Blackout 8 10 51 8 Sonic Creed Motema 218 209 9 2 53 8 Most Reports 8 9 7 1 Verve Jazz Ensemble Connect The Dots Lightgroove Media 218 217 1 10 38 2 10 6 3 1 John Coltrane Both Directions at Once - The Lost Album Impulse / Verve 199 237 -38 13 35 0 11 13 5 2 Antonio Adolfo Encontros - Orquestra Atlantica AAM Music 184 197 -13 12 39 1 12 11 7 7 Houston Person & Ron Carter Remember Love HighNote 181 204 -23 7 43 1 12 11 12 1 Bobby Sanabria West Side Story Re-Imagined Jazzheads 181 204 -23 11 32 0 14 18 27 14 Helen Sung Sung with Words (A Collaboration with Dana Stricker Street 179 168 11 4 41 0 Gioia) 15 14 6 6 Charlie Sepulveda & The Turnaround Songs For Nat HighNote 174 184 -10 7 40 2 16 14 14 11 Ben Paterson Live at Van Gelder’s Cellar Live 173 184 -11 8 37 0 17 21 14 4 Kamasi Washington Heaven and Earth Young Turks 153 151 2 13 29 0 18 16 10 2 Cory Weeds Little Big Band Explosion Cellar Live 151 181 -30 12 33 0 19 17 11 10 Marcus Miller Laid Black Blue Note 145 172 -27 14 25 0 20 20 17 2 Black Art Jazz Collective Armor Of Pride HighNote 143 165 -22 13 35 0 21 19 18 13 Mark Winkler & Cheryl Bentyne Eastern Standard Time Café Pacific 141 167 -26 6 37 0 22 22 25 22 James Austin, Jr. -

Jazz Publications and More

19397 Guts 261-280: 5/12/09 2:55 PM Page 261 JAZZ PUBLICATIONS AND MORE Section Page No. Jazz Instruction (All Instruments) .......................................262 Jazz Play-Along® Series ......................................................267 ABRSM Jazz Program .........................................................272 Artist Transcriptions® ..........................................................274 The Real Book .....................................................................276 Jazz Fake Books ..................................................................277 Jazz Bible Series..................................................................278 Paperback Songs ................................................................278 Other Fake Books ................................................................279 Carta Manuscript Paper.......................................................280 Gig Guides...........................................................................280 19397 Guts 261-280: 5/12/09 2:56 PM Page 262 262 JAZZ PUBLICATIONS ALL INSTRUMENTS BLUES CONCEPTS FOR JAZZ INSTRUCTION JAM – IMPROVISATION 40 PROGRESSIONS A Comprehensive Guide ADVANCED BLUES AND GROOVES for Performing and Teach- ETUDES IN ALL ing TWELVE KEYS SIT IN AND SOLO WITH A PROFESSIONAL BLUES by Richard De Rosa by Jordon Ruwe BAND! Houston Publishing Houston Publishing by Ed Friedland Using his vast musical experi - Includes 12 advanced blues Bring your local blues jam ence and the axiom “know - etudes four-measure excerpts session home! -

Cool Trombone Lover

NOVEMBER 2013 - ISSUE 139 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM ROSWELL RUDD COOL TROMBONE LOVER MICHEL • DAVE • GEORGE • RELATIVE • EVENT CAMILO KING FREEMAN PITCH CALENDAR “BEST JAZZ CLUBS OF THE YEAR 2012” SMOKE JAZZ & SUPPER CLUB • HARLEM, NEW YORK CITY FEATURED ARTISTS / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm ONE NIGHT ONLY / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm RESIDENCIES / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm Fri & Sat, Nov 1 & 2 Wed, Nov 6 Sundays, Nov 3 & 17 GARY BARTZ QUARTET PLUS MICHAEL RODRIGUEZ QUINTET Michael Rodriguez (tp) ● Chris Cheek (ts) SaRon Crenshaw Band SPECIAL GUEST VINCENT HERRING Jeb Patton (p) ● Kiyoshi Kitagawa (b) Sundays, Nov 10 & 24 Gary Bartz (as) ● Vincent Herring (as) Obed Calvaire (d) Vivian Sessoms Sullivan Fortner (p) ● James King (b) ● Greg Bandy (d) Wed, Nov 13 Mondays, Nov 4 & 18 Fri & Sat, Nov 8 & 9 JACK WALRATH QUINTET Jason Marshall Big Band BILL STEWART QUARTET Jack Walrath (tp) ● Alex Foster (ts) Mondays, Nov 11 & 25 Chris Cheek (ts) ● Kevin Hays (p) George Burton (p) ● tba (b) ● Donald Edwards (d) Captain Black Big Band Doug Weiss (b) ● Bill Stewart (d) Wed, Nov 20 Tuesdays, Nov 5, 12, 19, & 26 Fri & Sat, Nov 15 & 16 BOB SANDS QUARTET Mike LeDonne’s Groover Quartet “OUT AND ABOUT” CD RELEASE LOUIS HAYES Bob Sands (ts) ● Joel Weiskopf (p) Thursdays, Nov 7, 14, 21 & 28 & THE JAZZ COMMUNICATORS Gregg August (b) ● Donald Edwards (d) Gregory Generet Abraham Burton (ts) ● Steve Nelson (vibes) Kris Bowers (p) ● Dezron Douglas (b) ● Louis Hayes (d) Wed, Nov 27 RAY MARCHICA QUARTET LATE NIGHT RESIDENCIES / 11:30 - Fri & Sat, Nov 22 & 23 FEATURING RODNEY JONES Mon The Smoke Jam Session Chase Baird (ts) ● Rodney Jones (guitar) CYRUS CHESTNUT TRIO Tue Cyrus Chestnut (p) ● Curtis Lundy (b) ● Victor Lewis (d) Mike LeDonne (organ) ● Ray Marchica (d) Milton Suggs Quartet Wed Brianna Thomas Quartet Fri & Sat, Nov 29 & 30 STEVE DAVIS SEXTET JAZZ BRUNCH / 11:30am, 1:00 & 2:30pm Thu Nickel and Dime OPS “THE MUSIC OF J.J. -

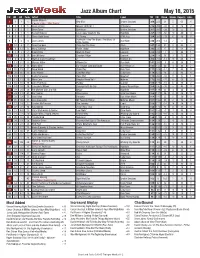

May 18, 2015 Jazz Album Chart

Jazz Album Chart May 18, 2015 TW LW 2W Peak Artist Title Label TW LW Move Weeks Reports Adds Harold Mabern 1 1 4 1 Afro Blue Smoke Sessions 364 333 31 5 63 4 2 weeks at No. 1 / Most Reports 2 4 3 1 Dave Stryker Messin’ With Mr. T Strikezone 276 299 -23 8 56 2 3 3 2 1 Steve Turre Spiritman Smoke Sessions 267 306 -39 10 55 1 4 2 1 1 Russell Malone Love Looks Good On You HighNote 257 313 -56 10 49 0 5 5 5 5 Steve Gadd Band 70 Strong BFM Jazz 254 283 -29 6 48 3 6 6 6 4 Jose James Yesterday I Had The Blues: The Music Of Blue Note 248 260 -12 7 57 2 Billie Holiday 7 13 8 7 David Sanborn Time And The River OKeh 247 196 51 5 43 2 8 8 12 8 Mary Stallings Feelin’ Good HighNote 242 225 17 5 54 2 9 7 7 7 Eliane Elias Made In Brazil Concord 223 230 -7 7 44 1 10 19 20 10 Ben Williams Coming Of Age Concord 214 158 56 3 52 7 11 9 9 3 Wolff & Clark Expedition 2 Random Act 202 214 -12 10 46 1 12 11 11 8 Marcus Miller Afrodeezia Blue Note 197 200 -3 8 36 1 13 25 21 13 Harry Allen For George, Cole And Duke Blue Heron Llc 183 143 40 4 46 7 14 15 19 12 Doug Webb Triple Play Posi-Tone 177 189 -12 7 40 0 15 20 86 15 Cory Weeds Condition Blue Cellar Live 174 156 18 2 46 8 15 10 10 1 Jacky Terrasson Take This! impulse! 174 206 -32 11 37 1 17 11 13 10 Marc Cary Rhodes Ahead Vol 2 Motema 173 200 -27 8 36 0 18 16 15 15 John Fedchock Fluidity Summit 169 179 -10 6 45 2 18 14 18 14 Cassandra Wilson Coming Forth By Day Legacy Recordings 169 195 -26 5 40 0 20 29 24 20 Pat Martino with Jim Ridl Nexus HighNote 167 139 28 4 44 2 21 39 44 21 Ben Sidran Blue Camus Unlimited -

SUS Ad for 2011 1

The Foundation for Music Education is announcing the 7th annual summer “Stars Under The Stars,” featuring the Brad Leali Quartet with Brad Leali on Saxophone, Claus Raible on piano, Giorgos Antiniou on bass, Alvester Garnett on drums, and joined by vocalist Martha Burks. The event will be on Friday, August 12, 2011 from 7:00 to 10:00 PM at the Louise Underwood Center. “Stars Under the Stars” is an evening concert benefitting music scholarships that will include an hour of socializing with sensational food and drink from “Stella’s.” The event benefits music education scholarships. Our traditional guest host and emcee will be local TV and Radio personality Jeff Klotzman. The “Stars” this year are brilliant world-class jazz artists from the United States, Greece, and Germany! For information about tickets and/or making donations for “Stars Under the Stars,” please call 806- 687-0861, 806-300-2474, and www.foundationformusiceducation.org. Information - The Quartet is captivating through the spontaneity and homogeneousness of the performance as well as with the communicative, non-verbal interaction of the four musicians. The band book consists, besides grand jazz classics, mainly of original compositions by the members. BRAD LEALI Saxophone http://www.bradleali.com/ CLAUS RAIBLE Piano, compositions and arrangements http://www.clausraible.com/Projects.htm GIORGIOS ANTONIOU Bass http://www.norwichjazzparty.com/Musician.asp?ID=22 ALVESTER GARNETT Drums http://www.alvestergarnett.com/ MARTHA BURKS Vocalist http://www.marthaburks.com/ Some comments about the quartet in the press: “This quartet enchanted the audience from the first, almost explosion like saxophone note and put them under their spell .. -

June 2020 Volume 87 / Number 6

JUNE 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 6 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Nov/Dec 2017 Volume 21, Issue 5

Bimonthly Publication of the Central Florida Jazz Society BLUE NOV/DEC 2017 VOLUME 21, ISSUE 5 NOTES Joey Alexander, Grammy-nominated fourteen- year-old piano prodigy, released his latest album in homage to his lifelong hero Thelonious Monk. “Sometimes, when I’m just practicing, playing something else, new melodic and rhythmic ideas come to me and I realize I’m actually starting to compose a song. I think writing strong tunes comes from listening to so much music from composers and artists I like. I would say that Monk has had the greatest influence on me. Hearing his pieces so many times had a great impact on me and inspired me to write my own pieces. I actually find it harder to interpret other people’s songs than write my own, because I have to figure out and feel what the song is about and find a way to make it my own. Monk taught me to groove, bounce, understand space, be patient, be simple, sometimes be mysterious but, most of all, to be joyful. In my arrangements, I try to stay true to the essence of his music — to treat it with the highest level of respect. Monk’s music is the essence of beauty.” https://www.villagevoice.com/2017/10/10/18-jazz- pianists-pay-tribute-to-thelonious-monk-on-his-100th- birthday/ CFJS 3208 W. Lake Mary Blvd., Suite 1720 President’s Lake Mary, FL 32746-3467 [email protected] Improv http://centralfloridajazzsociety.com By Carla Page Executive Committee The very first thing I want to do is apologize for our last Blue Carla Page Notes. -

STEFON HARRIS & BLACKOUT ( ~L,

A Secrest Artists Series Event STEFON HARRIS & BLACKOUT ( ~l, / Thursday September 9, 2004 7:30 pm Brendle Recital Hall Wake Forest University \\'i11:;/011-S11le111,Nort/, Caroli11a Stefon Harris & Blackout J time Grnmmy nomrnee vibraphonist Stefon Harris mtrmluccs his new band Bl,1ckout,on h1, CDEvolut11m(Blue Note records). Featuring an exciting blend of modern acousliL wund, writlen h, I l,1rris as wellas a monng rend1t1on of <;ting's'l/111/', the group has been hailed for "pursumg contemporary jau on llS own terms" (1/,c ~\'t1Slungtu11Pc>st). 1 hl' b.111d include~ Mar.: Ctr) on keyboard~. Derrick I lodge on h,1,s, Terrcon (,ully on drums and C.1seyBc111am111 on alto ~ax.The band has performed at the north sca jazz fc,tl\al, The Kenned, Center (Washmgton D( ), lhe F.gg (Alhany, NY) .1nd will embark upon a national tour Lo co111c1dewith its CD release Marc Cary ll.1ise<lin Washington, D.C., Marc ( ary has become known as one of the most ongmal Jilli p1,1msts111 '\'ew York A man of edccllc taste,, Carv has a strong post-hop foundation but has also explored Afro-Cuban rlwthms. eleclrOmLgroove mu~1c,and other dtrections with Im various ensembles. Upon arriv111g111 New York. Cary was t,1kenunder the wmg of Mickey !fa,, and Be,IVerHarm. Hts first h1g ttme gigs Lame m thL earl} '90, 1,ith Arthur Tarlor, Betty Carta, and Roy I l.1rgro\·e.In 199.J,he be..:ame Abbey Lm,olth p1a111,tand arranger. Carr's own records h,1veshown great promise. -

ELEVATION Songs from Afar

ELEVATION Songs from Afar Transylvanian expat pianist & composer Lucian Ban and ELEVATION celebrate their 2 n d album for Sunnyside records - Songs from Afar . Released in 2016 the album immediately garnered rave reviews and honors – DOWNBEAT BEST ALBUM OF THE YEAR , a 5* review in DB march 2016 issue, ALL ABOUT JAZZ calls it “a triumph of emotional and musical communication” and New York City Jazz Record talks of an “Inspiring and touching journey, that seamlessly blends the traditions of jazz and folk songs”. ”Alluring timelessness . a strong life-force that seems to flow through this music . like many of the great masters, pianist Lucian Ban makes personal art that feels universal” 5* STARS! “Songs From Afar is a triumph of emotional and musical communication, and is not to be missed” Streams of influence from the past and cultural identities sometimes merge with one’s quest for forms of expression. Songs From Afar represents two traditions, two musical worlds, and many musical elements coming together to fashion a unique identity that truly spans continents and styles. "Songs from afar is very personal for me because the album is intimately tied to my Romanian cultural heritage and to the jazz influences that help me find out more about where I come from – and where I’m going. It's not only the ancient Transylvanian folk songs that we approach in this recording, it's also how the other pieces and improvisations reflect the constant search for musical meaning" notes Transylvanian expat pianist and composer Lucian Ban talking about his 2 n d album with Elevation quartet in his 3 r d appearance for Sunnyside. -

Download the Blood on the Fields Playbill And

Thursday–Saturday Evening, February 21 –23, 2013, at 8:00 Wynton Marsalis, Managing & Artistic Director Greg Scholl, Executive Director Bloomberg is the Lead Corporate Sponsor of this performance. BLOOD ON THE FIELDS JAZZ AT LINCOLN CENTER ORCHESTRA WYNTON MARSALIS, Music Director, Trumpet RYAN KISOR, Trumpet KENNY RAMPTON, Trumpet MARCUS PRINTUP, Trumpet VINCENT GARDNER, Trombone, Tuba CHRIS CRENSHAW, Trombone ELLIOT MASON, Trombone SHERMAN IRBY, Alto & Soprano Saxophones TED NASH, Alto & Soprano Saxophones VICTOR GOINES, Tenor & Soprano Saxophones, Clarinet, Bass Clarinet WALTER BLANDING, Tenor & Soprano Saxophones CARL MARAGHI, Baritone Saxophone, Clarinet, Bass Clarinet ELI BISHOP, Guest Soloist, Violin ERIC REED, Piano CARLOS HENRIQUEZ, Bass ALI JACKSON, Drums Featuring GREGORY PORTER, Vocals KENNY WASHINGTON, Vocals PAULA WEST, Vocals There will be a 15-minute intermission for this performance. Please turn off your cell phones and other electronic devices. Jazz at Lincoln Center thanks its season sponsors: Bloomberg, Brooks Brothers, The Coca-Cola Company, Con Edison, Entergy, HSBC Bank, Qatar Airways, The Shops at Columbus Circle at Time Warner Center, and SiriusXM. MasterCard® is the Preferred Card of Jazz at Lincoln Center. Qatar Airways is a Premier Sponsor and Official Airline Partner of Jazz at Lincoln Center. This concert is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. ROSE THEATER JAZZ AT LINCOLN CENTER’S FREDERICK P. ROSE HALL jalc.org PROGRAM JAZZ AT LINCOLN CENTER 25TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON HONORS Since Jazz at Lincoln Center’s inception on August 3, 1987, when Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts initiated a three-performance summertime series called “Classical Jazz,” the organization has been steadfast in its commitment to broadening and deepening the public’s awareness of and participation in jazz. -

Instead Draws Upon a Much More Generic Sort of Free-Jazz Tenor

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. MARIAN McPARTLAND NEA Jazz Master (2000) Interviewee: Marian McPartland (March 20, 1918 – August 20, 2013) Interviewer: James Williams (March 8, 1951- July 20, 2004) Date: January 3–4, 1997, and May 26, 1998 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Description: Transcript, 178 pp. WILLIAMS: Today is January 3rd, nineteen hundred and ninety-seven, and we’re in the home of Marian McPartland in Port Washington, New York. This is an interview for the Smithsonian Institute Jazz Oral History Program. My name is James Williams, and Matt Watson is our sound engineer. All right, Marian, thank you very much for participating in this project, and for the record . McPARTLAND: Delighted. WILLIAMS: Great. And, for the record, would you please state your given name, date of birth, and your place of birth. McPARTLAND: Oh, God!, you have to have that. That’s terrible. WILLIAMS: [laughs] McPARTLAND: Margaret Marian McPartland. March 20th, 1918. There. Just don’t spread it around. Oh, and place of birth. Slough, Buckinghamshire, England. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 2 WILLIAMS: OK, so I’d like to, as we get some of your information for early childhood and family history, I’d like to have for the record as well the name of your parents and siblings and name, the number of siblings for that matter, and your location within the family chronologically. Let’s start with the names of your parents.