Saint-Saëns and Opera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Establishing the Tudor Dynasty: the Role of Francesco Piccolomini in Rome As First Cardinal Protector of England

2017 IV Establishing the Tudor Dynasty: The Role of Francesco Piccolomini in Rome as First Cardinal Protector of England Susan May Article: Establishing the Tudor Dynasty: The Role of Francesco Piccolomini in Rome as First Cardinal Protector of England Establishing the Tudor Dynasty: The Role of Francesco Piccolomini in Rome as First Cardinal Protector of England1 Susan May Abstract: Between 1492 and 1503, Francesco Todeschini Piccolomini (1439–1503) was the first officially appointed Cardinal Protector of England. This paper focuses on a select few of his activities executed in that capacity for Henry Tudor, King Henry VII. Drawing particularly on two unpublished letters, it underscores the importance for King Henry of having his most trusted supporters translated to significant bishoprics throughout the land, particularly in the northern counties, and explores Queen Elizabeth of York’s patronage of the hospital and church of St Katharine-by-the-Tower in London. It further considers the mechanisms through which artists and humanists could be introduced to the Tudor court, namely via the communication and diplomatic infrastructure of Italian merchant-bankers. This study speculates whether, by the end of his long incumbency of forty-three years at the Sacred College, uncomfortably mindful of the extent of a cardinal’s actual and potential influence in temporal affairs, Piccolomini finally became reluctant to wield the power of the purple. Keywords: Francesco Todeschini Piccolomini; Henry VII; early Tudor; cardinal protector; St Katharine’s; Italian merchant-bankers ope for only twenty-six days following his election, taking the name of Pius III (Fig. 1), Francesco Todeschini Piccolomini (1439–1503) has understandably been P overshadowed in reputation by his high-profile uncle, Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini, Pope Pius II (1458–64). -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

Anna Bolena Opera by Gaetano Donizetti

ANNA BOLENA OPERA BY GAETANO DONIZETTI Presentation by George Kurti Plohn Anna Bolena, an opera in two acts by Gaetano Donizetti, is recounting the tragedy of Anne Boleyn, the second wife of England's King Henry VIII. Along with Gioachino Rossini and Vincenzo Bellini, Donizetti was a leading composer of the bel canto opera style, meaning beauty and evenness of tone, legato phrasing, and skill in executing highly florid passages, prevalent during the first half of the nineteenth century. He was born in 1797 and died in 1848, at only 51 years of age, of syphilis for which he was institutionalized at the end of his life. Over the course of is short career, Donizetti was able to compose 70 operas. Anna Bolena is the second of four operas by Donizetti dealing with the Tudor period in English history, followed by Maria Stuarda (named for Mary, Queen of Scots), and Roberto Devereux (named for a putative lover of Queen Elizabeth I of England). The leading female characters of these three operas are often referred to as "the Three Donizetti Queens." Anna Bolena premiered in 1830 in Milan, to overwhelming success so much so that from then on, Donizetti's teacher addressed his former pupil as Maestro. The opera got a new impetus later at La Scala in 1957, thanks to a spectacular performance by 1 Maria Callas in the title role. Since then, it has been heard frequently, attracting such superstar sopranos as Joan Sutherland, Beverly Sills and Montserrat Caballe. Anna Bolena is based on the historical episode of the fall from favor and death of England’s Queen Anne Boleyn, second wife of Henry VIII. -

Samson Et Dalila De Camille Saint-Saëns

DOSSIER PÉDAGOGIQUE SAMSON © Christian Legay - Opéra-Théâtre de Metz Métropole de Metz - Opéra-Théâtre © Christian Legay ET DALILA DE CAMILLE SAINT-SAËNS CONTACTS ACTION CULTURELLE Marjorie Piquette / 01 69 53 62 16 / [email protected] Eugénie Boivin / 01 69 53 62 26 / [email protected] 1 SAMSON ET DALILA DE CAMILLE SAINT-SAËNS répétition générale : mercredi 7 novembre 2018 à 20h30 vendredi 9 novembre 2018 à 20h dimanche 11 novembre 2018 à 16h OPÉRA EN 3 ACTES ET 4 TABLEAUX Livret en français de Ferdinand Lemaire d’après la Bible (Juges 16, 4-30). Création au Théâtre de la Cour grand-ducale de Weimar, le 2 décembre 1877 grâce à Liszt et représenté à Paris en 1892. Direction Musicale David Reiland Mise en Scène Paul-Emile Fourny Assisté de Sylvie Laligne Décors Marco Japelj Costumes Brice Lourenço Lumières Patrice Willaume Chorégraphie Laurence Bolsigner-May Chef de Chant Nathalie Dang Chef de Chœur Nathalie Marmeuse Avec Samson Jean-Pierre Furlan Dalila Vikena Kamenica Le Grand Prêtre Alexandre Duhamel Abimélech Patrick Bolleire Un Vieillard Hébreu Wojtek Smilek Un Messager Daegweon Choi Le 1er Philistin Eric Mathurin Le 2e Philistin Jean-Sébastien Frantz Orchestre national d’Île-de-France Chœur de l’Opéra-Théâtre de Metz Métropole Chœurs Supplémentaires de l’Opéra de Massy Ballet de l’Opéra-Théâtre de Metz Métropole Production de l’Opéra-Théâtre de Metz Métropole En coproduction avec l’Opéra de Massy et le SNG-Opéra et Ballet National de Slovénie à Maribor ALLER PLUS LOIN : CONFÉRENCE CONFÉRENCE AUTOUR DE SAMSON ET DALILA : MARDI 6 NOVEMBRE À 19H Par Barbara Nestola, musicologue Entrée gratuite sur réservations au 01 60 13 13 13 (à partir du 23/10) 2 LE COMPOSITEUR On a pris la fâcheuse habitude de croire que, là où il y a des sons musicaux, il y a nécessairement de la musique. -

In the World of Music and Musicians

In the World of Music and Musicians The Late Camille Saiiit-Saens And His Visit to United States Programs of the Week of German and Sunday Tuesday Missions French Coniposcrg; Strauss Acolian Hall, 3 p. m. Concert by the Aeolian Hall, 3 p. m. Song recital and Failure in lneidents of icw York Symphony Societ;, : Margueritc d'Alvarez, contralto: Propagandism; Saint- ¦'.. Dleu.A. Nleolau ymphony No. 3.Rrahmi .Glock Saens's Sojourn Here; His Genius and Career A Comefly Ovorture".Oardlnei chanta .Ramaau oncerto ln C mlnor., .i>. ;ms ,. .Easthope Martin Percy ()r»ingor. .Franic Hrl«»ro Ilghf. Ruaalan Folk songs.I.iadow i' ' .. .Q. Btratffefe M I'-1 H. E. Krehbicl legree upon him, and the trifles Carnegie Hall. 3 p. m. Song rccitai I.nd . Rraumon-. By | already >y Emma Calve: t. uuy .Tachalkowaky have been to mentioncd. The other numbors of the UsnCes ^n Kti le n -...,- .Dargomysaky y!e reccntly permitted Sapho.Gounod .1 .."' Nl'ltli Maiden .narK-.n.yzaW program were his "Le Rouet d'Om- 'hreo old French Song*.Anonymoua .Tschatkowaky look upon the greatest of Gcrmany's Echoos des montagnes idc .k Chaoaaon phalc," Gcorg Schumann's "Liebes- La Rol Kenaud. ia.B. I'timiamri living composers and one of thc fore- frilhling" and Beethoven's "Eroica." (Chanson de Geates de Troubadours) !.¦¦ Solr .C. Dabuaay I.a Llsotte. l ..H»tnn most reprcsentatives, if not the fore- At the repetition of the program on jamen/o d'Arlane.Montev. d Tus OJ08 '.. .Alvarfz riades haleines ¦.' ¦.- the next Mr. Damrosch (XV Century).. Carisalml '.. .' Toroa..Alvara -. -

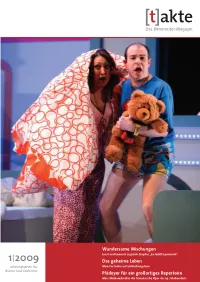

Takte 1-09.Pmd

[t]akte Das Bärenreiter-Magazin Wundersame Mischungen Ernst und komisch zugleich: Haydns „La fedeltà premiata” 1I2009 Das geheime Leben Informationen für Miroslav Srnka auf Entdeckungstour Bühne und Orchester Plädoyer für ein großartiges Repertoire Marc Minkowski über die französische Oper des 19. Jahrhunderts [t]akte 481018 „Unheilvolle Aktualität“ Abendzauber Das geheime Leben Telemann in Hamburg Ján Cikkers Opernschaffen Neue Werke von Thomas Miroslav Srnka begibt sich auf Zwei geschichtsträchtige Daniel Schlee Entdeckungstour Richtung Opern in Neueditionen Die Werke des slowakischen Stimme Komponisten J n Cikker (1911– Für Konstanz, Wien und Stutt- Am Hamburger Gänsemarkt 1989) wurden diesseits und gart komponiert Thomas Miroslav Srnka ist Förderpreis- feierte Telemann mit „Der Sieg jenseits des Eisernen Vorhangs Daniel Schlee drei gewichtige träger der Ernst von Siemens der Schönheit“ seinen erfolg- aufgeführt. Der 20. Todestag neue Werke: ein Klavierkon- Musikstiftung 2009. Bei der reichen Einstand, an den er bietet den Anlass zu einer neu- zert, das Ensemblestück „En- Preisverleihung im Mai wird wenig später mit seiner en Betrachtung seines um- chantement vespéral“ und eine Komposition für Blechblä- Händel-Adaption „Richardus I.“ fangreichen Opernschaffens. schließlich „Spes unica“ für ser und Schlagzeug uraufge- anknüpfen konnte. Verwickelte großes Orchester. Ein Inter- führt. Darüber hinaus arbeitet Liebesgeschichten waren view mit dem Komponisten. er an einer Kammeroper nach damals beliebt, egal ob sie im Isabel Coixets Film -

B-RECORDS Ascanio B-RECORDS Ascanio P.1

B-RECORDS Ascanio P.1 B-RECORDS Ascanio P.2 B-RECORDS Ascanio P.4 CAMILLE SAINT-SAËNS — ASCANIO Opéra en cinq Actes et sept Tableaux livret de Louis Gallet Première exécution absolue de la version conforme au manuscrit autographe de 1888. Concerts enregistrés les 24 et 26 novembre 2017 à Genève. Guillaume Tourniaire direction musicale Raphaël Hardmeyer Charles Quint Olivia Doutney Une Ursuline Jean-François Lapointe Benvenuto Cellini Joé Bertili Pagolo Choeur de la Haute école Bernard Richter Ascanio de musique de Genève Ève-Maud Hubeaux Scozzone Choeur du Grand Théâtre de Genève Jean Teigten François Ier Alan Woodbridge chef de chœur Karina Gauvin La Duchesse d'Étampes Clémence Tilquin Colombe D'Estourville Orchestre de la Haute école Mohammed Haidar Un Mendiant de musique de Genève Bastien Combe D'Estourville Maxence Billiemaz D'Orbec Joidy Blanco flûte solo B-RECORDS Ascanio P.5 B-RECORDS Ascanio P.6 ORCHESTRE DE LA HAUTE CLARINETTES CHŒUR DU GRAND THÉÂTRE ALTOS ÉCOLE DE MUSIQUE DE GENÈVE Marina Yamashita, Mio Yamashita DE GENÈVE Leilla Attigui, Camille Bourquin, Pierre-Antoine Marçais Roberto Balistreri Ornella Corvi, Alina Delgadillo, chef d’orchestre assistant BASSONS Assistant du chef de choeur Zoé Vauconsant Aline Kalchofner, Citlalli Medina Durán, VIOLONS Carla Rouaud (et contrebasson) SOPRANOS TÉNORS Lucie Menier (1er VS), Camille Guilpain Fosca Aquaro, Chloé Chavanon, Paul Belmonte, Quentin Monteil, (2ème VS), Jou Chan, Sen Chan, CORS Magali Duceau, Györgyi Garreau-Sarlos, Jeka Pawel, Marin Yonchev Seat Byeol Choi, Benjamin -

N OTES on CONTRIBUTORS Yearbook and in the Early Drama

N OTES ON CONTRIBUTORS Debra Barrett-Graves is Assistant Professor of English at California State University-Hayward. Her articles have appeared in Shakespeare Yearbook and in The Early Drama, Art, and Music Review. She collabo rated with Levin and Carney on an essay collection, Elizabeth 1: Always Her Own Free Woman (Ashgate, 2003) and she, Carney, and Levin were among the coauthors of Extraordinary Women 0/ the Medieval and Renaissance World (Greenwood Publishers, 2000). Jo Eldridge Carney is Associate Professor of English at The College of New Jersey. She is the editor of Renaissance and Reformation, 1500-1620 (Greenwood Publishers, 2000), which was chosen by CHOICE as an Outstanding Academic Book. Carney, Barrett-Graves, and Levin were among the authors of Extraordinary Women 0/ the Medieval and Renaissance World (Greenwood Publishers, 2000). She also collaborated with Levin and Barrett-Graves on an essay collection, Elizabeth L Always Her Own Free Woman (Ashgate, 2003). Joy Currie is completing her Ph.D. in Renaissance and Romanticism at the University of Nebraska where she received the Maud Hammond Fling Fellowship. She has twice received the John Robinson Prize for best paper from the English Department and recently published an article in Medievalia. Susan Dunn-Hensley teaches at the University of Kansas where she is completing her Ph.D. in English Renaissance literature; her dissertation is on women healers and witches in early modern drama. Timothy G. Elston is completing his Ph.D. in History at the University ofNebraska where he has received the Barnes Fellowship to support his dissertation research on Catherine of Aragon. -

Repertoire & Opera Explorer / New in September 2020

Repertoire & Opera Explorer / New in September 2020 No. 2105 André-Ernest-Modeste Gretry Lucille (with French libretto) 37 EUR No. 2107 Christoph Willibald Gluck Iphigénie en Tauride (with German and French libretto) 39 EUR No. 2589 Antoine Bessems 5th Fantaisie op. 25 (Souvenirs élégiaques) for viola or cello and piano. Arrangement for piano cello by Adrien François Servais (score and parts / first print) 22 EUR No. 2734 Konstantia Gourzi Rezitativ Antigone for Soprano or Tenor and Piano (first print) 16 EUR No. 4299 Granville Bantock Old English Suite, arranged for small orchestra 22 EUR No. 4331 Eugen d'Albert Symphonic prelude to the opera Tiefland Op.34 18 EUR No. 4342 Wilhelm Stenhammar Reverenza for orchestra 17 EUR No. 4345 Paul von Klenau Die Weise von Liebe und Tod des Cornets Christoph Rilke, for baritone, choir and orchestra 41 EUR No. 4346 Hugo Kaun Two Symphonic Poems Op.43: Minnehaha / Hiawatha 24 EUR No. 4356 Carl Reinecke Hakon Jarl Op. 142, symphonic poem 34 EUR No. 4359 Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari “Invocation”, Concerto for Violoncello and Orchestra op. 31 27 EUR No. 4364 Hans Pfitzner Scherzo in C minor for orchestra 15 EUR No. 4367 Otakar Ostrcil Impromptu Op.13 for orchestra 29 EUR No. 4373 Heinrich von Herzogenberg Symphony No. 2 Op.70 24 EUR No. 4383 Viktor Kosenko Moldavian Poem op. 26 for orchestra 43 EUR No. 4384 Paul Büttner Slavonian Dance in G Minor 18 EUR No. 4391 Antonio Salieri Concerto for Organ and Orchestra in C Major 20 EUR No. 4394 Ketil Hvoslef Trio for Tretten (Acotral) for 4 voices and 9 instruments (first print) 30 EUR New B numbers (Piano Reductions / Vocal Scores) No. -

Spring 2018 L. Jackson Anna Bolena

Opera Appreciation Synopses - Spring 2018 L. Jackson Anna Bolena Synopsis Anna Bolena is a tragedia lirica, or opera, in two acts by Gaetano Donizetti. Librettist – Felice Romani after Ippolito Pindemonte's Enrico VIII ossia Anna Bolena and Alessandro Pepoli's Anna Bolena Premiered on December 26, 1830 at the Teatro Carcano,Milan. Principal Roles: Anna Bolena (Anne Boleyn) Soprano Enrico (Henry VIII) Baritone Giovanna (Jane Seymour) Mezzo Soprano Lord Rochefort (George Boleyn) Bass Lord Percy Tenor Smeton (Mark Smeaton) Contralto Harvey (Court Officia) Tenor Act 1 Scene One: Night, Windsor Castle, Queen's apartments Courtiers comment that the queen’s star is setting, because the king’s fickle heart burns with another love. Jane Seymour enters to attend a call by the Queen, Anna enters and notes that people seem sad. The queen admits being troubled to Jane. At the queen’s request, her page Smeton plays the harp and sings to cheer the people present. The queen asks him to stop. Unheard by any one else, she says to herself that the ashes of her first love are still burning, and that she is now unhappy in her vain splendor. All leave, except Jane. Henry VIII enters, he tells Jane that soon she will have no rival, that the altar has been prepared for her, that she will have husband, sceptre, and throne. Each leaves by a different door. Scene Two: Day. Around Windsor Castle Lord Rochefort, Anna’s brother, is surprised to meet Lord Richard Percy, who has been called back to England from exile by Henry VIII. -

Donizetti's Anna Bolena Opens on November 10

620 North First Street, Minneapolis, MN 55401 tel: 612-333-2700 fax: 612-333-0869 box office hours: Monday – Friday, 9 a.m.–6 p.m. News Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 22 O CTOBER 2012 CONTACT : Daniel Zillmann , 612.342.1612 or [email protected] Donizetti’s Anna Bolena opens on November 10 Minnesota Opera’s 50 th Anniversary Season continues with the final installment of Donizetti’s Tudor trilogy, led by Music Director Michael Christie and a quartet of powerful voices: Keri Alkema, Kyle Ketelsen, Lauren McNeese and David Portillo What: Gaetano Donizetti’s Anna Bolena Sung in Italian with English translations projected above the stage. Where: Ordway, 345 Washington Street, Saint Paul, MN 55102 When: Saturday, November 10 , 7:30 pm Tuesday, November 13 , 7:30 pm Thursday, November 15 , 7:30 pm Saturday, November 17 , 7:30 pm Sunday, November 18 , 2pm Tickets: $20 – $200 . Call the Minnesota Opera Ticket Office at 612.333.6669, Monday –Friday, 9am –6pm, or purchase online at mnopera.org. Media: An online press kit (available now on Dropbox at bit.ly/mnoperapressroom ) includes full bios, artist headshots, design renderings, production photos and other useful resources. Contact Communications Manager Daniel Zillmann to take advantage of the following interview, photo and video opportunities at dress rehearsals at Ordway: Wednesday, November 7, 7:30 pm and Thursday, November 8, 7:30 pm . Preview: Minnesota Opera hosts its second Social Media Preview Night of the season for bloggers and tweeters, including complimentary appetizers, a social hour and pre- rehearsal discussion with Music Director Michael Christie at Amsterdam, and exclusive access to the dress rehearsal on Thursday, November 8, 5:30 pm. -

CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA/PAGLIACCI Cast Biographies Cavalleria Rusticana

CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA/PAGLIACCI Cast Biographies Cavalleria Rusticana Before making his San Francisco Opera debut in 1993 as Rodolfo in La Bohème, tenor Roberto Aronica (Turiddu) studied with famed singer Carlo Bergonzi and completed his training at the Accademia Chigiana in Siena. He made his professional debut as the Duke of Mantua in Rigoletto at Teatro Municipal in Santiago de Chile. More recent engagements have included Manrico in Il Trovatore at the Teatro Comunale di Bologna, the title role of Don Carlos at the Royal Opera House, Pinkerton in Madama Butterfly at the Gran Teatre del Liceu in Barcelona, Calaf in Turandot at Turin’s Teatro Regio, and Alfredo in La Traviata at the Metropolitan Opera. In 2018, Aronica performs Pinkerton at the Metropolitan Opera, Paolo in Francesca da Rimini at the Teatro alla Scala, and Don Carlo at the Teatro Comunale di Bologna. Russian mezzo-soprano Ekaterina Semenchuk (Santuzza) made her San Francisco Opera debut in 2015 as Federica in Luisa Miller and in 2016 she returned as Amneris in Aida. Her recent engagements include Eboli in Don Carlo at Teatro alla Scala and Royal Opera, Covent Garden; Azucena in Il Trovatore with Rome Opera, St. Petersburg’s Mariinsky Theatre, and Covent Garden; Fricka in Das Rheingold at the Edinburgh International Festival; and Lady Macbeth in Macbeth at Los Angeles Opera opposite Plácido Domingo. Career highlights encompass Marina Mnishek in Boris Godunov at the Metropolitan Opera; Azucena and Amneris at Milan’s Teatro alla Scala; Iocasta in Oedipus Rex and Ascanio in Benvenuto Cellini at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées; the title role of Carmen at Arena di Verona; Preziosilla in La Forza del Destinoand Amneris with Berlin State Opera; Didon in Les Troyens at the Mariinsky Theatre, Carnegie Hall, and in Vienna and Tokyo; Laura Adorno in La Gioconda and Dalila inSamson et Dalila at Rome Opera; Giovanna Seymour in Anna Bolena at the Vienna State Opera; and Eboli and Azucena at the Salzburg Festival.