Branding Hoover's FBI 8/5/16 1:06 PM Page V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

J. Edgar Hoover, "Speech Before the House Committee on Un‐American Activities" (26 March 1947)

Voices of Democracy 3 (2008): 139‐161 Underhill 139 J. EDGAR HOOVER, "SPEECH BEFORE THE HOUSE COMMITTEE ON UN‐AMERICAN ACTIVITIES" (26 MARCH 1947) Stephen Underhill University of Maryland Abstract: J. Edgar Hoover fought domestic communism in the 1940s with illegal investigative methods and by recommending a procedure of guilt by association to HUAC. The debate over illegal surveillance in the 1940s to protect national security reflects the on‐going tensions between national security and civil liberties. This essay explores how in times of national security crises, concerns often exist about civil liberties violations in the United States. Key Words: J. Edgar Hoover, Communism, Liberalism, National Security, Civil Liberties, Partisanship From Woodrow Wilson's use of the Bureau of Investigation (BI) to spy on radicals after World War I to Richard Nixon's use of the renamed Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to spy on U.S. "subversives" during Vietnam, the balance between civil liberties and national security has often been a contentious issue during times of national crisis.1 George W. Bush's use of the National Security Agency (NSA) to monitor the communications of suspected terrorists in the United States is but the latest manifestation of a tension that spans the existence of official intelligence agencies.2 The tumult between national security and civil liberties was also visible during the early years of the Cold War as Republicans and Democrats battled over the U.S. government's appropriate response to the surge of communism internationally. Entering the presidency in 1945, Harry S Truman became privy to the unstable dynamic between Western leaders and Josef Stalin over the post‐war division of Eastern Europe.3 Although only high level officials within the executive branch intimately understood this breakdown, the U.S. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 27 April 2017 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Lu, Jennifer (2017) 'Covert and overt operations : interwar political policing in the United States and the United Kingdom.', American historical review., 122 (3). pp. 727-757. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/122.3.727 Publisher's copyright statement: This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced version of an article accepted for publication in American Historical Review following peer review. The version of record Lu, Jennifer (2017). Covert and Overt Operations: Interwar Political Policing in the United States and the United Kingdom. American Historical Review 122(3): 727-757 is available online at: https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/122.3.727 Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk “Covert and Overt Operations: Interwar Political Policing in the United States and the United Kingdom” Manuscript accepted for publication by the American Historical Review Jennifer Luff Readers should consult the final copy-edited version published in the American Historical Review SINCE THE EARLY DAYS OF THE Cold War, observers have reproached American anticommunism by invoking the example of British moderation. -

Eastwood, Dicaprio Try to Capture First FBI Director's Life in 'J. Edgar'

09 November 2011 | voaspecialenglish.com Eastwood, DiCaprio Try to Capture First FBI Director's Life in 'J. Edgar' AP From left, Leonardo DiCaprio, Armie Hammer and director Clint Eastwood at the premiere of "J. Edgar" last week in Los Angeles (You can download an MP3 of this story at voaspecialenglish.com) DOUG JOHNSON: Welcome to AMERICAN MOSAIC in VOA Special English. (MUSIC) I’m Doug Johnson. Today we play music from American Idol winner Scotty McCreery ... And we answer a question about American whiskey ... But first, it is history at the movie theater where a new film opens about former law enforcement chief J. Edgar Hoover. "J. Edgar" DOUG JOHNSON: The movie "J. Edgar" opens across America today. The film is about J. Edgar Hoover, the first director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Hoover was a complex and powerful man. He helped develop the FBI into an efficient and effective crime solving agency. However, in later years, many people 2 questioned the methods used by Hoover and his investigators. Bob Doughty tells more about the man and the movie. BOB DOUGHTY: Clint Eastwood directed the movie "J. Edgar." He grew up in the time when, in his words, "Hoover was always top cop." Eastwood said he had heard different stories about the former FBI director. Some of them were very critical. But Eastwood said anybody who stays in a job as long as Hoover did is going to create some enemies. J. Edgar Hoover was the leader of the FBI and the agency it developed from for almost fifty years. -

Suspect Until Proven Guilty, a Problematization of State Dossier Systems Via Two Case Studies: the United States and China

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations Fall 2009 Suspect Until Proven Guilty, a Problematization of State Dossier Systems via Two Case Studies: The United States and China Kenneth N. Farrall University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Communication Technology and New Media Commons, International and Intercultural Communication Commons, and the Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons Recommended Citation Farrall, Kenneth N., "Suspect Until Proven Guilty, a Problematization of State Dossier Systems via Two Case Studies: The United States and China" (2009). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 51. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/51 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/51 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Suspect Until Proven Guilty, a Problematization of State Dossier Systems via Two Case Studies: The United States and China Abstract This dissertation problematizes the "state dossier system" (SDS): the production and accumulation of personal information on citizen subjects exceeding the reasonable bounds of risk management. SDS - comprising interconnecting subsystems of records and identification - damage individual autonomy and self-determination, impacting not only human rights, but also the viability of the social system. The research, a hybrid of case-study and cross-national comparison, was guided in part by a theoretical model of four primary SDS driving forces: technology, political economy, law and public sentiment. Data sources included government documents, academic texts, investigative journalism, NGO reports and industry white papers. The primary analytical instrument was the juxtaposition of two individual cases: the U.S. -

The Original Documents Are Located in Box 4, Folder “COINTELPRO” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 4, folder “COINTELPRO” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Ron Nessen donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 4 of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY ATTORNEY GENERAL WASHINGTON, D.C. 20!130 November 14, 1974 MEMORANDUM FOR: FROM: SUBJECT: COINTELPRO Attaqhed for your use at your press briefing on Monday, November 18, are the following: A. Proposed questions and answers for your own use. I suggest that you refer all specific inquiries concerning the or1g1n, scope, details etq. of COINTELPRO to the Department of Justice; B. Questions and answers which will be used by the Attorney General in his own press conference on that day; C. The COINTELPRO report to be released in conjunction with the Attorney General's press conference; and D. A memorandum from the Attorney General to the FBI Director which will also be released in conjunction with the Attorney General's press conference. -

Civillibertieshstlookinside.Pdf

Civil Liberties and the Legacy of Harry S. Truman The Truman Legacy Series, Volume 9 Based on the Ninth Truman Legacy Symposium The Civil Liberties Legacy of Harry S. Truman May 2011 Key West, Florida Edited by Richard S. Kirkendall Civil Liberties and the LEGACY of Harry S. Truman Edited by Richard S. Kirkendall Volume 9 Truman State University Press Copyright © 2013 Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri, 63501 All rights reserved tsup.truman.edu Cover photo: President Truman delivers a speech on civil liberties to the American Legion, August 14, 1951 (Photo by Acme, copy in Truman Library collection, HSTL 76- 332). All reasonable attempts have been made to locate the copyright holder of the cover photo. If you believe you are the copyright holder of this photograph, please contact the publisher. Cover design: Teresa Wheeler Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Civil liberties and the legacy of Harry S. Truman / edited by Richard S. Kirkendall. pages cm. — (Truman legacy series ; 9) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61248-084-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-61248-085-5 (ebook) 1. Truman, Harry S., 1884–1972—Political and social views. 2. Truman, Harry S., 1884–1972—Influence. 3. Civil rights—United States—History—20th century. 4. United States. Constitution. 1st–10th Amendments. 5. Cold War—Political aspects—United States. 6. Anti-communist movements—United States— History—20th century. 7. United States—Politics and government—1945–1953. I. Kirkendall, Richard Stewart, 1928– E814.C53 2013 973.918092—dc23 2012039360 No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any format by any means without written permission from the publisher. -

Prefering Order to Justice Laura Rovner

American University Law Review Volume 61 | Issue 5 Article 3 2012 Prefering Order to Justice Laura Rovner Jeanne Theoharis Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr Part of the Courts Commons Recommended Citation Rovner, Laura, and Jeanne Theoharis. "Prefering Order to Justice." American University Law Review 61, no.5 (2012): 1331-1415. This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Prefering Order to Justice This essay is available in American University Law Review: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr/vol61/iss5/3 ROVNER‐THEOHARIS.OFF.TO.PRINTER (DO NOT DELETE) 6/14/2012 7:12 PM PREFERRING ORDER TO JUSTICE ∗ LAURA ROVNER & JEANNE THEOHARIS In the decade since 9/11, much has been written about the “War on Terror” and the lack of justice for people detained at Guantanamo or subjected to rendition and torture in CIA black sites. A central focus of the critique is the unreviewability of Executive branch action toward those detained and tried in military commissions. In those critiques, the federal courts are regularly celebrated for their due process and other rights protections. Yet in the past ten years, there has been little scrutiny of the hundreds of terrorism cases tried in the Article III courts and the state of the rights of people accused of terrrorism-related offenses in the federal system. -

The FBI: Protecting the Homeland in the 21St Century

EMBARGOED until 10 a.m., March 25, 2015 UNCLASSIFIED (U) The FBI: Protecting the Homeland in the 21st Century (U) Report of the Congressionally-directed (U) 9/11 Review Commission To (U) The Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation By (U) Commissioners Bruce Hoffman Edwin Meese III Timothy J. Roemer EMBARGOED(U) March 2015 EMBARGOED until 10 a.m., March 25, 2015 UNCLASSIFIED EMBARGOED until 10 a.m., March 25, 2015 UNCLASSIFIED EMBARGOED 1 EMBARGOED until 10 a.m., March 25, 2015 UNCLASSIFIED EMBARGOED until 10 a.m., March 25, 2015 UNCLASSIFIED (U) TABLE OF CONTENTS (U) Introduction: The 9/11 Review Commission…..……….………........ p. 3 (U) Chapter I: Baseline: The FBI Today…………………………….. p. 15 (U) Chapter II: The Sum of Five Cases………………….……………. p. 38 (U) Chapter III: Anticipating New Threats and Missions…………....... p. 53 (U) Chapter IV: Collaboration and Information Sharing………………. p. 73 (U) Chapter V: New Information Related to the 9/11 Attacks………… p. 100 (U) Key Findings and Recommendations…………………………………. p. 108 (U) Conclusion: ………………………………………………………… p. 118 (U) Appendix A: Briefs Provided by FBI Headquarters Divisions.…..… p. 119 (U) Appendix B: Interviews Conducted……… ………………………. p. 121 (U) Appendix C: Select FBI Intelligence Program Developments…….… p. 122 (U) Appendix D: Acronyms……………… …………………………… p. 124 EMBARGOED 2 EMBARGOED until 10 a.m., March 25, 2015 UNCLASSIFIED EMBARGOED until 10 a.m., March 25, 2015 UNCLASSIFIED (U) INTRODUCTION THE FBI 9/11 REVIEW COMMISSION (U) The FBI 9/11 Review Commission was established in January 2014 pursuant to a congressional mandate.1 The United States Congress directed the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI, or the “Bureau”) to create a commission with the expertise and scope to conduct a “comprehensive external review of the implementation of the recommendations related to the FBI that were proposed by the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States (commonly known as the 9/11 Commission).”2 The Review Commission was tasked specifically to report on: 1. -

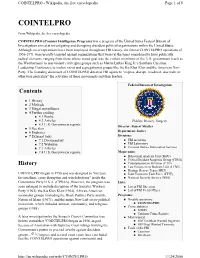

COINTELPRO - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Page 1 of 8

COINTELPRO - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 of 8 COINTELPRO From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia COINTELPRO (Counter Intelligence Program) was a program of the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation aimed at investigating and disrupting dissident political organizations within the United States. Although covert operations have been employed throughout FBI history, the formal COINTELPRO operations of 1956-1971 were broadly targeted against organizations that were (at the time) considered to have politically radical elements, ranging from those whose stated goal was the violent overthrow of the U.S. government (such as the Weathermen) to non-violent civil rights groups such as Martin Luther King Jr.'s Southern Christian Leadership Conference to violent racist and segregationist groups like the Ku Klux Klan and the American Nazi Party. The founding document of COINTELPRO directed FBI agents to "expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize" the activities of these movements and their leaders. Federal Bureau of Investigation Contents 1 History 2 Methods 3 Illegal surveillance 4 Further reading 4.1 Books 4.2 Articles Fidelity, Bravery, Integrity 4.3 U.S. Government reports Director: Robert Mueller 5 See also Department: Justice 6 Endnotes 7 External links Divisions: 7.1 Documentary FBI Academy 7.2 Websites FBI Laboratory Criminal Justice Information Services 7.3 Articles 7.4 U.S. Government reports Major units: Behavioral Analysis Unit (BAU) Critical Incident Response Group (CIRG) History Counterterrorism Division (CTD) Law Enforcement Bulletin Unit (LEBU) Hostage Rescue Team (HRT) COINTELPRO began in 1956 and was designed to "increase Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF) factionalism, cause disruption and win defections" inside the National Security Service (NSS) Communist Party U.S.A. -

Espionage and Intelligence Gathering Other Books in the Current Controversies Series

Espionage and Intelligence Gathering Other books in the Current Controversies series: The Abortion Controversy Issues in Adoption Alcoholism Marriage and Divorce Assisted Suicide Medical Ethics Biodiversity Mental Health Capital Punishment The Middle East Censorship Minorities Child Abuse Nationalism and Ethnic Civil Liberties Conflict Computers and Society Native American Rights Conserving the Environment Police Brutality Crime Politicians and Ethics Developing Nations Pollution The Disabled Prisons Drug Abuse Racism Drug Legalization The Rights of Animals Drug Trafficking Sexual Harassment Ethics Sexually Transmitted Diseases Family Violence Smoking Free Speech Suicide Garbage and Waste Teen Addiction Gay Rights Teen Pregnancy and Parenting Genetic Engineering Teens and Alcohol Guns and Violence The Terrorist Attack on Hate Crimes America Homosexuality Urban Terrorism Illegal Drugs Violence Against Women Illegal Immigration Violence in the Media The Information Age Women in the Military Interventionism Youth Violence Espionage and Intelligence Gathering Louise I. Gerdes, Book Editor Daniel Leone,President Bonnie Szumski, Publisher Scott Barbour, Managing Editor Helen Cothran, Senior Editor CURRENT CONTROVERSIES San Diego • Detroit • New York • San Francisco • Cleveland New Haven, Conn. • Waterville, Maine • London • Munich © 2004 by Greenhaven Press. Greenhaven Press is an imprint of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of Thomson Learning, Inc. Greenhaven® and Thomson Learning™ are trademarks used herein under license. For more information, contact Greenhaven Press 27500 Drake Rd. Farmington Hills, MI 48331-3535 Or you can visit our Internet site at http://www.gale.com ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems—without the written permission of the publisher. -

U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation Washington, D.C. 20535 August 24, 2020 MR. JOHN GREENEWALD JR. SUITE

U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation Washington, D.C. 20535 August 24, 2020 MR. JOHN GREENEWALD JR. SUITE 1203 27305 WEST LIVE OAK ROAD CASTAIC, CA 91384-4520 FOIPA Request No.: 1374338-000 Subject: List of FBI Pre-Processed Files/Database Dear Mr. Greenewald: This is in response to your Freedom of Information/Privacy Acts (FOIPA) request. The FBI has completed its search for records responsive to your request. Please see the paragraphs below for relevant information specific to your request as well as the enclosed FBI FOIPA Addendum for standard responses applicable to all requests. Material consisting of 192 pages has been reviewed pursuant to Title 5, U.S. Code § 552/552a, and this material is being released to you in its entirety with no excisions of information. Please refer to the enclosed FBI FOIPA Addendum for additional standard responses applicable to your request. “Part 1” of the Addendum includes standard responses that apply to all requests. “Part 2” includes additional standard responses that apply to all requests for records about yourself or any third party individuals. “Part 3” includes general information about FBI records that you may find useful. Also enclosed is our Explanation of Exemptions. For questions regarding our determinations, visit the www.fbi.gov/foia website under “Contact Us.” The FOIPA Request number listed above has been assigned to your request. Please use this number in all correspondence concerning your request. If you are not satisfied with the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s determination in response to this request, you may administratively appeal by writing to the Director, Office of Information Policy (OIP), United States Department of Justice, 441 G Street, NW, 6th Floor, Washington, D.C. -

Obama Truthers--He's Gay and His BC Is a Total Forgery

Obama truthers--he's gay and his BC is a total forgery NewsFollowUp.com Franklin Scandal Omaha search pictorial index sitemap home .... OBAMA TOP 10 FRAUD .... The Right and Left Obama Truthers Obama's public personal records The Right and are a total fraud. We agree. It's most importantly a blackmail issue and the public's duty to uncover deception. Left Obama MORE and Donald Trump: Trump's video, $5 million to charities if he releases personal records. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MgOq9pBkY0I&feature=youtu.be&hd=1 Truthers Selective Service card VP Joe Biden Purple Hotel Spencer, Bland & Young Limbaugh, Corsi more 14 Expert Reports on technical analysis of the Obama public records Jerome Corsi believes Obama is Gay. Rush Limbaugh's Straight Entertainment says Obama is gay. HillBuzz interview with Larry Sinclair (gay tryst with Obama) Israel Science & Technology says Obama's birth certificate is a forgery based on expert analysis of the typography and layout of elements in the long-form birth certificate. ... layers Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio (Arizona) determined in 2012 there is probable cause to suspect the document released by the White House as Barack Obama’s birth certificate is a forgery MORE News for the 99% ...................................Refresh F5...archive home NFU MOST ACTIVE PA Go to Alphabetic list 50th Anniversary of JFK assassination Academic Freedom "Event of a Lifetime" at the Fess Conference Parker Double Tree Inn. Obama Death List JFKSantaBarbara. Rothschild Timeline Bush / Clinton Body Count Back to Obama Home Obama Gay Chicago Spencer, Bland and Young Examiner Who is Barack Hussein Obama/Barry Chicago 2012 Campaign Soetoro? It is alleged that Barack Obama has spent $950,000 to $1.7 million with 11 law firms in 12 Lawsuit dismissed below states to block disclosure of his personal records; which includes birth information, K-12 education, Stuart Levine, Ashley Turton below Occidental College, Columbia University, and Clinton, Sinclair Harvard Law School.