1 the Life and Thought of Charles De Foucauld: a Christian Eremitical Vocation to Islam and His Contribution to the Understandin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The “Doctrine of Discovery” and Terra Nullius: a Catholic Response

1 The “Doctrine of Discovery” and Terra Nullius: A Catholic Response The following text considers and repudiates illegitimate concepts and principles used by Europeans to justify the seizure of land previously held by Indigenous Peoples and often identified by the terms Doctrine of Discovery and terra nullius. An appendix provides an historical overview of the development of these concepts vis-a-vis Catholic teaching and of their repudiation. The presuppositions behind these concepts also undergirded the deeply regrettable policy of the removal of Indigenous children from their families and cultures in order to place them in residential schools. The text includes commitments which are recommended as a better way of walking together with Indigenous Peoples. Preamble The Truth and Reconciliation process of recent years has helped us to recognize anew the historical abuses perpetrated against Indigenous peoples in our land. We have also listened to and been humbled by courageous testimonies detailing abuse, inhuman treatment, and cultural denigration committed through the residential school system. In this brief note, which is an expression of our determination to collaborate with First Nations, Inuit and Métis in moving forward, and also in part a response to the Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, we would like to reflect in particular on how land was often seized from its Indigenous inhabitants without their consent or any legal justification. The Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops (CCCB), the Canadian Catholic Aboriginal Council and other Catholic organizations have been reflecting on the concepts of the Doctrine of Discovery and terra nullius for some time (a more detailed historical analysis is included in the attached Appendix). -

The Pre-History of Subsidiarity in Leo XIII

Journal of Catholic Legal Studies Volume 56 Number 1 Article 5 The Pre-History of Subsidiarity in Leo XIII Michael P. Moreland Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcls This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Catholic Legal Studies by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FINAL_MORELAND 8/14/2018 9:10 PM THE PRE-HISTORY OF SUBSIDIARITY IN LEO XIII MICHAEL P. MORELAND† Christian Legal Thought is a much-anticipated contribution from Patrick Brennan and William Brewbaker that brings the resources of the Christian intellectual tradition to bear on law and legal education. Among its many strengths, the book deftly combines Catholic and Protestant contributions and scholarly material with more widely accessible sources such as sermons and newspaper columns. But no project aiming at a crisp and manageably-sized presentation of Christianity’s contribution to law could hope to offer a comprehensive treatment of particular themes. And so, in this brief essay, I seek to elaborate upon the treatment of the principle of subsidiarity in Catholic social thought. Subsidiarity is mentioned a handful of times in Christian Legal Thought, most squarely with a lengthy quotation from Pius XI’s articulation of the principle in Quadragesimo Anno.1 In this proposed elaboration of subsidiarity, I wish to broaden the discussion of subsidiarity historically (back a few decades from Quadragesimo Anno to the pontificate of Leo XIII) and philosophically (most especially its relation to Leo XIII’s revival of Thomism).2 Statements of the principle have historically been terse and straightforward even if the application of subsidiarity to particular legal questions has not. -

Religion and the Abolition of Slavery: a Comparative Approach

Religions and the abolition of slavery - a comparative approach William G. Clarence-Smith Economic historians tend to see religion as justifying servitude, or perhaps as ameliorating the conditions of slaves and serving to make abolition acceptable, but rarely as a causative factor in the evolution of the ‘peculiar institution.’ In the hallowed traditions, slavery emerges from scarcity of labour and abundance of land. This may be a mistake. If culture is to humans what water is to fish, the relationship between slavery and religion might be stood on its head. It takes a culture that sees certain human beings as chattels, or livestock, for labour to be structured in particular ways. If religions profoundly affected labour opportunities in societies, it becomes all the more important to understand how perceptions of slavery differed and changed. It is customary to draw a distinction between Christian sensitivity to slavery, and the ingrained conservatism of other faiths, but all world religions have wrestled with the problem of slavery. Moreover, all have hesitated between sanctioning and condemning the 'embarrassing institution.' Acceptance of slavery lasted for centuries, and yet went hand in hand with doubts, criticisms, and occasional outright condemnations. Hinduism The roots of slavery stretch back to the earliest Hindu texts, and belief in reincarnation led to the interpretation of slavery as retribution for evil deeds in an earlier life. Servile status originated chiefly from capture in war, birth to a bondwoman, sale of self and children, debt, or judicial procedures. Caste and slavery overlapped considerably, but were far from being identical. Brahmins tried to have themselves exempted from servitude, and more generally to ensure that no slave should belong to 1 someone from a lower caste. -

Of Issionaryresearch Contextualization: the Theory, the Gap, the Challenge Darrell L

Vol. 21, No.1 nternatlona• January 1997 etln• Contextualization: Mission in the Balance u st when the coming of A.D. 2000, with its latent verted to Christianity out of Buddhism, I became so aggressive triumphalism, stirs talk of fulfilling the Great Commis and felt forced to turn my back on my Buddhist family and sion,J here we are bringing up the nettlesome issue of denounce my culture. Now I realize ... that I can practice a contextualization. In the lead article of this issue, Darrell cherished value of meekness, affirm much of my Thai culture, Whiteman recalls a student at Asbury Seminary who had and follow Jesus in the Thai way." wrestled with feelings of alienation toward her Thai family and In our pursuit of authentic contextualization we may be culture. Is she typical of converts in Buddhist lands? Does a lack privileged to discover in other cultures a foretaste of the trea of contextualization help to account for the fact that after four sures that will strengthen and guide us for faithfulness in the centuries of Catholic mission and a century and a half of Protes kingdom. tant mission, barely one percent of the population of Thailand has been attracted to the Christian Gospel? G. C. Oosthuizen follows Whiteman with a detailed account of the runaway appeal of the Zionist churches among South On Page African blacks. Soon, reports Oosthuizen, half of the population 2 Contextualization: The Theory, the Gap, the of Christian blacks will be members of Zionist-type African Challenge Independent Churches. Meanwhile, according to the SouthAfri Darrell L. -

The Holy See

The Holy See IN PLURIMIS ENCYCLICAL OF POPE LEO XIII ON THE ABOLITION OF SLAVERY To the Bishops of Brazil. Amid the many and great demonstrations of affection which from almost all the peoples of the earth have come to Us, and are still coming to Us, in congratulation upon the happy attainment of the fiftieth anniversary of Our priesthood, there is one which moves Us in a quite special way. We mean one which comes from Brazil, where, upon the occasion of this happy event, large numbers of those who in that vast empire groan beneath the yoke of slavery, have been legally set free. And this work, so full of the spirit of Christian mercy, has been offered up in cooperation with the clergy, by charitable members of the laity of both sexes, to God, the Author and Giver of all good things, in testimony of their gratitude for the favor of the health and the years which have been granted to Us. But this was specially acceptable and sweet to Us because it lent confirmation to the belief, which is so welcome to Us, that the great majority of the people of Brazil desire to see the cruelty of slavery ended, and rooted out from the land. This popular feeling has been strongly seconded by the emperor and his august daughter, and also by the ministers, by means of various laws which, with this end in view, have been introduced and sanctioned. We told the Brazilian ambassador last January what a consolation these things were to Us, and We also assured him that We would address letters to the bishops of Brazil in behalf of these unhappy slaves. -

The Jesus Caritas Fraternities in the United States: the Early History 1963 – 1973

PO BOX 763 • Franklin Park, IL 60131 • [P] 260-786-JESU (5378) Website: www.JesusCaritasUSA.org • [E] [email protected] THE JESUS CARITAS FRATERNITIES IN THE UNITED STATES: THE EARLY HISTORY 1963 – 1973 by Father Juan Romero INTRODUCTION At the national retreat for members of the Jesus Caritas Fraternity of priests, held at St. John’s Seminary in Camarillo, California in July 2010, Father Jerry Devore of Bridgeport, Connecticut asked me, in the name of the National Council, to write an early history of Jesus Caritas in the United States. (For that retreat, almost fifty priests from all over the United States had gathered for a week within the Month of Nazareth, in which a smaller number of priests were participating for the full month.) This mini-history is to complement A New Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Msgr. Bryan Karvelis of Brooklyn, New York (RIP), and the American Experience of Jesus Caritas Fraternities by Father Dan Danielson of Oakland, California. It proposes to record the beginnings of the Jesus Caritas Fraternities in the USA over its first decade of existence from 1963 to 1973, and it will mark the fifth anniversary of the beatification of the one who inspired them, Little Brother Blessed Charles de Foucault. It purports to be an “acts of the apostles” of some of the Jesus Caritas Fraternity prophets and apostles in the USA, a collective living memory of this little- known dynamic dimension of the Church in the United States. It is not an evaluation of the Fraternity, much less a road map for its future growth and development. -

BMH.WS1751.Pdf

ROIILN COSANTA. HISTORY, 1913-21 BUREAU OF MILITARY STATMENT BY WITNESS. 1,751 DOCUMENT NO. W.S. Witness The Hon, Justice Cahir Davitt, Dungriffan, 2, Sidney Parade Ave., Dublin. Identity. Circuit Judge Republican Courts, Dáil Éireann 1920-1922; Judge Advocate General, Irish Free State Army, 1922-1926. Subject. First Judge Advocate General of the Defence Forces of the Provisional Government and afterwards of the Irish Free State. Conditions,if any, Stipulatedby Witness. To be placed under seal for a period of 25 years as from 9th January, 1959. FileNo 1,637 Form B.S.M.2 JUDGE ADVOCATE GENERAL. PREFACE. Some few years ago, at the request of Colonel John Joyce, I wrote a memorandum upon the Dá11 Court for the Bureau of Military History. I had kept no diaries for the years 1920 to 1922 and had very few records with which to refresh my memory of the events which I attempted to describe. The memorandum had therefore to take the form of reminiscences of my personal experiences as a Judge of the Dáil Courts. What follows is intended to be a kind of sequel to that memorandum and a similar record of my personal experiences as the first Judge-Advocate-General of the Defence Forces of the Provisional Government and afterwards of the Irish Free State. I kept no diaries f or the years 1922 to 1926; and will have again to depend upon my unaided memory with occasional resort, in all probability, to the contemporary press and books of reference for the purpose of checking or ascertaining names or dates or the sequence of events. -

Saints and Blessed People

Saints and Blessed People Catalog Number Title Author B Augustine Tolton Father Tolton : From Slave to Priest Hemesath, Caroline B Barat K559 Madeleine Sophie Barat : A Life Kilroy, Phil B Barbarigo, Cardinal Mark Ant Cardinal Mark Anthony Barbarigo Rocca, Mafaldina B Benedict XVI, Pope Pope Benedict XVI , A Biography Allen, John B Benedict XVI, Pope My Brother the Pope Ratzinger, Georg B Brown It is I Who Have Chosen You Brown, Judie B Brown Not My Will But Thine : An Autobiography Brown, Judie B Buckley Nearer, My God : An Autobiography of Faith Buckley Jr., William F. B Calloway C163 No Turning Back, A Witness to Mercy Calloway, Donald B Casey O233 Story of Solanus Casey Odell, Catherine B Chesterton G. K. C5258 G. K. Chesterton : Orthodoxy Chesterton, G. K. B Connelly W122 Case of Cornelia Connelly, The Wadham, Juliana B Cony M3373 Under Angel's Wings Maria Antonia, Sr. B Cooke G8744 Cooke, Terence Cardinal : Thy Will Be Done Groeschel, Benedict & Weber, B Day C6938 Dorothy Day : A Radical Devotion Coles, Robert B Day D2736 Long Loneliness, The Day, Dorothy B de Foucauld A6297 Charles de Foucauld (Charles of Jesus) Antier, Jean‐Jacques B de Oliveira M4297 Crusader of the 20th Century, The : Plinio Correa de Oliveira Mattei, Riberto B Doherty Tumbleweed : A Biography Doherty, Eddie B Dolores Hart Ear of the Heart :An Actress' Journey from Hollywood to Holy Hart, Mother Dolores B Fr. Peter Rookey P Father Peter Rookey : Man of Miracles Parsons, Heather B Fr.Peyton A756 Man of Faith, A : Fr. Patrick Peyton Arnold, Jeanne Gosselin B Francis F7938 Francis : Family Man Suffers Passion of Jesus Fox, Fr. -

I Worry Until Midnight and from Then on I Let God Worry

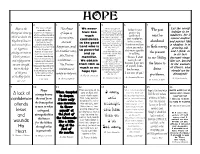

HOPE 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 The virtue of hope Hope is the The object We never The virtue of Let the world responds to the hope is so pleasing Today in your The past aspiration to happiness have too indulge in its theological virtue by of hope is, to God that He prayer you which God has placed in much has declared that confirmed must be madness, for it which we desire the the heart of every man; He feels delight in cannot endure it takes up the hopes in one way, confidence those who trust your resolution kingdom of heaven that inspire men's in Him: “The Lord to be a saint. abandoned and passes like eternal in the good taketh pleasure in activities and purifies I understand you a shadow. It is and eternal life as Lord who is them that hope them so as to order them happiness, and, in His Mercy” when you make to God's mercy, growing old, our happiness, to the Kingdom of so powerful (Ps. 46:11). this more specific heaven; it keeps man in another way, And He promises and I think, is placing our trust in from discouragement; and so victory over his by adding, the present in its last Christ's promises it sustains him during the Divine merciful. enemies, “I know I shall times of abandonment; perseverance in to our fidelity, decrepit stage. grace, and succeed, not and relying not on it opens up his heart in assistance . We obtain eternal glory to But we, buried expectation of eternal from Him as the man who because I am sure the future to in the wounds our own strength, beatitude. -

The Catholic Church Regarding African Slavery in Brazil During the Emancipation Period from 1850 to 1888

Bondage and Freedom The role of the Catholic Church regarding African slavery in Brazil during the emancipation period from 1850 to 1888 Matheus Elias da Silva Supervisor Associate Professor Roar G. Fotland This Master's Thesis is carried out as a part of the education at MF Norwegian School of Theology and is therefore approved as a part of this education. MF Norwegian School of Theology, [2014, Spring] AVH5010: Master's Thesis [60 ECTS] Master in Theology [34.658 words] 1 Table of Contents Chapter I – Introduction ..................................................................................................................5 1.1 - Personal Concern ....................................................................................................................5 1.2 - Background..............................................................................................................................5 1.3 - The Research........................................................................................................................... 5 1.4 - Methodology............................................................................................................................6 1.5 - Sources.................................................................................................................................... 9 1.6 - Research History .................................................................................................................... 9 1.7 - Terminology...........................................................................................................................10 -

Inte Rna Tio Nal Bul Letin

INTERNATIONAL BULLETIN OF THE LAY FRATERNITY CHARLES DE FOUCAULD Nº 89- Nazareth- Back to the Roots June 2013 News from our Association Bread of Life « Nazareth » Meeting at with our Pope Viviers Francis Summary Editorial 3 Only God Can – Father Guy Gilbert 4 Nazareth – Claudio and Sylvana Chiaruttini 5 The God of Jesus Christ – Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger 13 An inspiring new reading with a poetic approach 14 Fraternities News 15 -Africa 15 -America 28 -Asia 33 -Europe 34 -Arab World 36 Association Meeting at Viviers: April 1st-7th 42 -How CDF has read and meditated the Bible 42 - The prayer of the Christians in the land of Islam A Testimony from Algeria 44 Practical Information 47 An inspiring new reading with a poetic approach It’s not Easy 48 Editorial Dear lay brothers and sisters throughout the whole world, We hope that you are all well. This 89th edition of the Bulletin is dedicated to our life of Nazareth, a return to the roots. Nazareth? What is that? Nazareth is a city situated in northern Israel, in Galilee. But it is also the place where Jesus Christ spent his childhood. His whole life was hidden and is not described by the evangelists. Nazareth just had to attract Brother Charles with its simplicity and it was a changing point in his life. As a consequence, the lives of many people have changed. In this 89th edition of the International Bulletin, we share with you some thoughts about Nazareth and particularly everyone`s personal Nazareth. We share the bread of life with our new pope Francis who never stops inviting us to follow Jesus Christ and to be witnesses of his Love. -

Legacy of a Spiritual Master Who Loved the Desert Eightieth Anniversary of the Death of Charles De-Foucauld

Legacy of a spiritual master who loved the desert Eightieth Anniversary of the Death of Charles De-Foucauld On 1 December 1996, in hundreds of places all over the world, Charles de Foucauld's followers gathered for the 80th anniversary of his death; they did so in their own way, discreetly; they have no distinctive feature, they have blended with the peoples to whom they wish to belong, the anonymous crowd of the poor, the rejected and those "far from God", as de Foucauld used to say the marginalized, or more simply, the common people who lead ordinary lives; they shun the spectacular: they want above all "to belong to the community", as Jesus of Nazareth did in his so- called hidden life. Since they do not seek great publicity but rather avoid it—to be consistent with their vocation— newspapers and magazines say little about Charles de Foucauld's spiritual heritage. It should also be said that speaking of this legacy raises a further difficulty: in the cause for his beatification, Fr de Foucauld is rightly not considered a "founder" of congregations. Although he scattered to the four winds "rules", "directives" and "counsels", and indicated ways of living the religious or lay life according to Nazareth, in his lifetime he founded no institutions. And his followers are as varied as the members of the Church: priests, men and women religious, lay people, found in very different Church structures, but in their real differences they are all recognizable for the same affinity. The principal leaders of the groups assembled in associations, secular institutes and religious congregations which constitute the "spiritual family of Charles de Foucauld" meet every year in Rome or some other part of the world (most recently Haiti) for a week of information and review; in 1996, there were 18 officially approved groups.