The Catholic University of America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue of the Earl Marshal's Papers at Arundel

CONTENTS CONTENTS v FOREWORD by Sir Anthony Wagner, K.C.V.O., Garter King of Arms vii PREFACE ix LIST OF REFERENCES xi NUMERICAL KEY xiii COURT OF CHIVALRY Dated Cases 1 Undated Cases 26 Extracts from, or copies of, records relating to the Court; miscellaneous records concerning the Court or its officers 40 EARL MARSHAL Office and Jurisdiction 41 Precedence 48 Deputies 50 Dispute between Thomas, 8th Duke of Norfolk and Henry, Earl of Berkshire, 1719-1725/6 52 Secretaries and Clerks 54 COLLEGE OF ARMS General Administration 55 Commissions, appointments, promotions, suspensions, and deaths of Officers of Arms; applications for appointments as Officers of Arms; lists of Officers; miscellanea relating to Officers of Arms 62 Office of Garter King of Arms 69 Officers of Arms Extraordinary 74 Behaviour of Officers of Arms 75 Insignia and dress 81 Fees 83 Irregularities contrary to the rules of honour and arms 88 ACCESSIONS AND CORONATIONS Coronation of King James II 90 Coronation of King George III 90 Coronation of King George IV 90 Coronation of Queen Victoria 90 Coronation of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra 90 Accession and Coronation of King George V and Queen Mary 96 Royal Accession and Coronation Oaths 97 Court of Claims 99 FUNERALS General 102 King George II 102 Augusta, Dowager Princess of Wales 102 King George III 102 King William IV 102 William Ewart Gladstone 103 Queen Victoria 103 King Edward VII 104 CEREMONIAL Precedence 106 Court Ceremonial; regulations; appointments; foreign titles and decorations 107 Opening of Parliament -

October 2019 New Releases

October 2019 New Releases what’s inside featured exclusives PAGE 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately! 82 Vinyl Audio 3 CD Audio 17 FEATURED RELEASES Music Video DVD & Blu-ray 52 SPYRO GYRA - WOODSTOCK: DINOSAUR JR. - VINYL TAP 3 DAYS THAT CHANGED WHERE YOU BEEN: Non-Music Video EVERYTHING 2CD DELUXE EXPANDED DVD & Blu-ray 57 EDITION Order Form 90 Deletions and Price Changes 93 800.888.0486 RINGU COLLECTION MY SAMURAI JIRGA 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 (COLLECTOR’S EDITION) FRED SCHNEIDER & THE SPYRO GYRA - WEDDING PRESENT - www.MVDb2b.com SUPERIONS - VINYL TAP TOMMY 30 BAT BABY MVD: RAISING HELL THIS FALL! We celebrate October with a gallery of great horror films, lifting the lid off HELLRAISER and HELLBOUND: HELLRAISER II with newly restored Blurays. The original and equally terrifying sequel are restored to their crimson glory by Arrow Video! HELLRAISER and its successor overflow with new film transfers and myriad extras that will excite any Pinhead! The Ugly American comes alive in the horror dark comedy AN AMERICAN WEREWOLF IN LONDON. Another fine reboot from Arrow Video, this deluxe pack will have you howling! Arrow also hits the RINGU with a release of this iconic Japanese-Horror film that spawned The Ring film franchise. Creepy and disturbing, RINGU concerns a cursed videotape, that once watched, will kill you in seven days! Watching this Bluray will have no such effect, but please, don’t answer the phone! TWO EVIL EYES from Blue Underground is a “double dose of terror” from two renowned directors, George A. Romero and Dario Argento. -

Steadfast and Shrewd Heroines: the Defence of Chastity in the Latin Post-Nicene Passions and the Greek Novels

Steadfast and shrewd heroines: the defence of chastity in the Latin post-Nicene passions and the Greek novels ANNELIES BOSSU Ghent University 1. Introduction Over the past decades, the disparaging opinion of the Greek ‘ideal’ novels which goes back to at least Rohde’s pioneer modern study of 18761 has been abandoned: they are no longer viewed as literary inferior texts. Together with this renewed and favourable attention, research into the novels’ inter- connections with other ancient narrative texts increased. Unsurprisingly, the interplay with the Roman novel was explored. It has been argued that Petro- nius parodied the Greek novels2 and attention has been drawn to thematic and structural correspondences between the Greek novels and both Apuleius’ Metamorphoses3 and the Historia Apollonii Regis Tyri.4 Whereas the Chris- tian overtone in the latter work is debated,5 the novels’ interaction with ————— 1 Rohde 1876. 2 This thesis was first raised by Heinze in 1899 and has received wide acceptance since, see e.g. Conte 1996, esp. 31-34 on his adaptation of Heinze’s thesis. For objections against the thesis, see Morgan 2009, 40-47. 3 See e.g. the contributions of Brethes, Frangoulidis, Harrison, and Smith to Paschalis, Frangoulidis, Harrison, Zimmerman 2007. 4 See Schmeling 20032, 540-544 on both similarities and dissimilarities between the Histo- ria Apollonii (HA) and the Greek novels, especially Xenophon of Ephesus’ Ephesiaca. 5 On the HA as a Christian product, see Kortekaas 1984, 101-106, 116-118, and 2004, 17- 24, and Hexter 1988, 188. For objections against the Christian overtone, see Schmeling 20032, 531-537. -

Tinctoris's Minimum Opus

Tinctoris’s Minimum Opus ROB C. WEGMAN (Princeton University) he story has long been known and often been told: as a student at the TUniversity at Orléans, Johannes Tinctoris made a fool of himself.1 Proud of his accomplishments, and pleased especially with his literary prowess, he allowed his vanity to slip through and leave a permanent record, in full view of all posterity, in a document that would survive the centuries. That document, which is still kept at Orléans today, is precious for several reasons – not the least of which is that it is the only surviving text written in the theorist’s own hand. Yet what makes it truly invaluable is what he reveals about himself, intentionally and, perhaps, unintentionally. The text has been transcribed and edited by several modern scholars, and the facts of the case are well known.2 Yet the story they tell remains a footnote to the larger story of Tinctoris’s life. My aim in the pages that follow is to take another close look at the text, and to give it more of the interpretive scrutiny that we are accustomed to give to other documents from this period. Like so many medieval texts, the Orléans document raises questions that may not be obvious in a face-value reading. Indeed, upon sustained scrutiny we may soon find ourselves wondering what, exactly, is the story it tells, how much of a fool Tinctoris really made of himself, and who, ultimately, has the last laugh. Before delving into those questions, however, let us begin by recapitulating the story, and providing some of the context necessary to analyze it. -

The Evolution of the Roman Calendar Dwayne Meisner, University of Regina

The Evolution of the Roman Calendar Dwayne Meisner, University of Regina Abstract The Roman calendar was first developed as a lunar | 290 calendar, so it was difficult for the Romans to reconcile this with the natural solar year. In 45 BC, Julius Caesar reformed the calendar, creating a solar year of 365 days with leap years every four years. This article explains the process by which the Roman calendar evolved and argues that the reason February has 28 days is that Caesar did not want to interfere with religious festivals that occurred in February. Beginning as a lunar calendar, the Romans developed a lunisolar system that tried to reconcile lunar months with the solar year, with the unfortunate result that the calendar was often inaccurate by up to four months. Caesar fixed this by changing the lengths of most months, but made no change to February because of the tradition of intercalation, which the article explains, and because of festivals that were celebrated in February that were connected to the Roman New Year, which had originally been on March 1. Introduction The reason why February has 28 days in the modern calendar is that Caesar did not want to interfere with festivals that honored the dead, some of which were Past Imperfect 15 (2009) | © | ISSN 1711-053X | eISSN 1718-4487 connected to the position of the Roman New Year. In the earliest calendars of the Roman Republic, the year began on March 1, because the consuls, after whom the year was named, began their years in office on the Ides of March. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} on Art and Life by John Ruskin History of the Victorian Art Critic and Writer John Ruskin

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} On Art and Life by John Ruskin History of the Victorian Art Critic and Writer John Ruskin. Ruskin200.com is no longer available here. Please visit ruskinprize.co.uk/manchester instead. Who Was John Ruskin? John Ruskin was undoubtedly a fascinating character, one of the most famous art critics of the Victorian era. His many talents included philosophy, philanthropy, and writing. His books spanned many genres, including geology, myths, and literature. Ruskin's Personal Life. Ruskin had a complex personality and today would be described as bipolar, as he often suffered bouts of depression. For long periods, the state of his mental health rendered him powerless to do anything. His first relationship was a failure. He was said to be disgusted by his wife's body, leading to a divorce on the grounds of consummation not having happened. A second love affair was marred by tragedy as the object of his affections died of anorexia at the age of 27. Ruskin's Books. A prolific writer, Ruskin, published several important works on a great many subjects. His first volume of Modern Painters was a very influential piece, written when he was only 24. His alternative views on popular artists brought him to the attention of the art establishment. The Stones of Venice was published in 1851 and discussed Ruskin's love of Venice and its architecture. His beliefs that the classical style represented a need to control civilisation are still studied today. There is much to learn about John Ruskin, and there is a museum dedicated to him, located in the Lake District. -

RTE No 19 Interior

THE ASTONISHING MISSIONARY JOURNEYS OF THE APOSTLE ANDREW George Alexandrou, international reporter, writer, and political commentator, on his thou- sand-page book in Greek, He Raised the Cross on the Ice, exploring the sources, traditions, routes and cultures of St. Andrew’s apostolate. George’s own enthusiasm and love for St. Andrew made our long months of working together more than an assignment, it became a shared pilgrimage. BEGINNINGS RTE: George, please tell us about your background and how you began this epic project of reconstructing St. Andrew’s journeys. GEORGE: Yes, but before I begin, I have to say that at certain times in my life I’ve been very blind. I can speak about the Taliban, about international pol- icy, about government leaders, but I’m not righteous enough to speak or write about St. Andrew. This is how I feel and I must say so at the beginning. My background is that I went to the university as one of the best students in Greece, but dropped out to become a hippie and a traveler, a fighter for the ecological movement, and then just an “easy rider.” When I returned to Greece, by chance, or perhaps God’s will, I turned to journalism and was Mosaic of St. Andrew, Cathedral of Holy Apostle Andrew, Patras, Greece. 3 Road to Emmaus Vol. V, No. 4 (#19) the astonishing missionary journeys of the apostle andrew quite successful. I became the director of an important Greek historical You find Greek faces in strange places all over the world. There are journal, had a rather flashy career in Cyprus as a TV news director, and descendants of Greek-Chinese in Niya, China’s Sinkiang region, as I said, traveled around the world for some major journalist associations. -

John Archibald Goodall, F.S.A

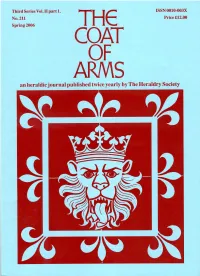

Third Series Vol. II part 1. ISSN 0010-003X No. 211 Price £12.00 Spring 2006 THE COAT OF ARMS an heraldic journal published twice yearly by The Heraldry Society THE COAT OF ARMS The journal of the Heraldry Society Third series Volume II 2006 Part 1 Number 211 in the original series started in 1952 The Coat of Arms is published twice a year by The Heraldry Society, whose registered office is 53 High Street, Burnham, Slough SL1 7JX. The Society was registered in England in 1956 as registered charity no. 241456. Founding Editor † John Brooke-Little, C.V.O., M.A., F.H.S. Honorary Editors C. E. A. Cheesman, M.A., PH.D., Rouge Dragon Pursuivant M. P. D. O'Donoghue, M.A., Bluemantle Pursuivant Editorial Committee Adrian Ailes, B.A., F.S.A., F.H.S. Andrew Hanham, B.A., PH.D Advertizing Manager John Tunesi of Liongam PLATE 3 . F.S.A , Goodall . A . A n Joh : Photo JOHN GOODALL (1930-2005) Photographed in the library of the Society of Antiquaries with a copy of the Parliamentary Roll (ed. N.H. Nicolas, 1829). JOHN ARCHIBALD GOODALL, F.S.A. (1930-2005) John Goodall, a member of the editorial committee of this journal, and once a fre• quent contributor to its pages, died in St Thomas' Hospital of an infection on 23 November 2005. He was suffering from cancer. His prodigiously wide learning spread back to the Byzantine and ancient worlds, and as far afield as China and Japan, but particularly focused on medieval rolls of arms, on memorial brasses and on European heraldry. -

What Information Do We Hold?

ST GEORGE’S CHAPEL ARCHIVES & CHAPTER LIBRARY Research guides No.1 The Order of the Garter Foundation and composition The Most Noble Order of the Garter, the oldest surviving Order of Chivalry in the world, was founded by Edward III in or just before 1348. St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle, became and remains the spiritual home of the Order and holds the annual Service of Thanksgiving on Garter Day which is attended by the Sovereign and Companions of the Order. The origins of the Order’s blue garter and motto, ‘Honi Soit Qui Mal Y Pense’ (Shame on Him Who Thinks Evil of It), are uncertain. The date of the foundation of the Order of the Garter is a subject of historiographical controversy, largely due to the absence of early records of the Order. The French chronicler Froissart, writing between 1370 and 1400 and drawing upon the account of the English ecclesiastic Adam of Murimuth, claimed that the foundation of the Order coincided with the feast held by Edward III at Windsor Castle in January or February of 1344. At this feast, according to Murimuth, Edward had declared an intention to establish a Round Table of three hundred knights ‘in the same manner and estate as the Lord Arthur, formerly King of England’. It is now widely believed that Froissart wrongly conflated the events of the feast held in 1344 with the actual foundation of the Order of the Garter, which occurred later in the 1340s and possibly coincided with the establishment of the College of St George, Windsor, in 1348. -

D'elboux Manuscripts

D’Elboux Manuscripts © B J White, December 2001 Indexed Abstracts page 63 of 156 774. Halsted (59-5-r2c10) • Joseph ASHE of Twickenham, in 1660 • arms. HARRIS under Bradbourne, Sevenoaks • James ASHE of Twickenham, d1733 =, d. Edmund BOWYER of Richmond Park • Joseph WINDHAM = ……, od. James ASHE 775. Halsted (59-5-r2c11) • Thomas BOURCHIER of Canterbury & Halstead, d1486 • Thomas BOURCHIER the younger, kinsman of Thomas • William PETLEY of Halstead, d1528, 2s. Richard = Alyce BOURCHIER, descendant of Thomas BOURCHIER the younger • Thomas HOLT of London, d1761 776. Halsted (59-5-r2c12) • William WINDHAM of Fellbrigge in Norfolk, m1669 (London licence) = Katherine A, d. Joseph ASHE 777. Halsted (59-5-r3c03) • Thomas HOLT of London, d1761, s. Thomas HOLT otp • arms. HOLT of Lancashire • John SARGENT of Halstead Place, d1791 = Rosamund, d1792 • arms. SARGENT of Gloucestershire or Staffordshire, CHAMBER • MAN family of Halstead Place • Henry Stae MAN, d1848 = Caroline Louisa, d1878, d. E FOWLE of Crabtree in Kent • George Arnold ARNOLD = Mary Ann, z1760, d1858 • arms. ROSSCARROCK of Cornwall • John ATKINS = Sarah, d1802 • arms. ADAMS 778. Halsted (59-5-r3c04) • James ASHE of Twickenham, d1733 = ……, d. Edmund BOWYER of Richmond Park • Joseph WINDHAM = ……, od. James ASHE • George Arnold ARNOLD, d1805 • James CAZALET, d1855 = Marianne, d1859, d. George Arnold ARNOLD 779. Ham (57-4-r1c06) • Edward BUNCE otp, z1684, d1750 = Anne, z1701, d1749 • Anne & Jane, ch. Edward & Anne BUNCE • Margaret BUNCE otp, z1691, d1728 • Thomas BUNCE otp, z1651, d1716 = Mary, z1660, d1726 • Thomas FAGG, z1683, d1748 = Lydia • Lydia, z1735, d1737, d. Thomas & Lydia FAGG 780. Ham (57-4-r1c07) • Thomas TURNER • Nicholas CARTER in 1759 781. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

HIP-HOP LIFE AND LIVELIHOOD IN NAIROBI, KENYA By JOHN ERIK TIMMONS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2018 © 2018 John Erik Timmons To my parents, John and Kathleen Timmons, my brothers, James and Chris Timmons, and my wife, Sheila Onzere ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The completion of a PhD requires the support of many people and institutions. The intellectual community at the University of Florida offered incredible support throughout my graduate education. In particular, I wish to thank my committee members, beginning with my Chair Richard Kernaghan, whose steadfast support and incisive comments on my work is most responsible for the completion of this PhD. Luise White and Brenda Chalfin have been continuous supporters of my work since my first semester at the University of Florida. Abdoulaye Kane and Larry Crook have given me valuable insights in their seminars and as readers of my dissertation. The Department of Anthropology gave me several semesters of financial support and helped fund pre-dissertation research. The Center for African Studies similarly helped fund this research through a pre-dissertation fellowship and awarding me two years’ support the Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowship. Another generous Summer FLAS Fellowship was awarded through Yale’s MacMillan Center Council on African Studies. My language training in Kiswahili was carried out in the classrooms of several great instructors, Rose Lugano, Ann Biersteker, and Kiarie wa Njogu. The United States Department of Education generously supported this fieldwork through a Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Award. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan)