Morrison's Haven Harbour TEACHER's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Addendum: University of Nottingham Letters : Copy of Father Grant’S Letter to A

Nottingham Letters Addendum: University of 170 Figure 1: Copy of Father Grant’s letter to A. M. —1st September 1751. The recipient of the letter is here identified as ‘A: M: —’. Source: Reproduced with the kind permission of the Department of Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottinghan. 171 Figure 2: The recipient of this letter is here identified as ‘Alexander Mc Donell of Glengarry Esqr.’. Source: Reproduced with the kind permission of the Department of Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottinghan. 172 Figure 3: ‘Key to Scotch Names etc.’ (NeC ¼ Newcastle of Clumber Mss.). Source: Reproduced with the kind permission of the Department of Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottinghan. 173 Figure 4: In position 91 are the initials ‘A: M: —,’ which, according to the information in NeC 2,089, corresponds to the name ‘Alexander Mc Donell of Glengarry Esqr.’, are on the same line as the cant name ‘Pickle’. Source: Reproduced with the kind permission of the Department of Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottinghan. Notes 1 The Historians and the Last Phase of Jacobitism: From Culloden to Quiberon Bay, 1746–1759 1. Theodor Fontane, Jenseit des Tweed (Frankfurt am Main, [1860] 1989), 283. ‘The defeat of Culloden was followed by no other risings.’ 2. Sir Geoffrey Elton, The Practice of History (London, [1967] 1987), 20. 3. Any subtle level of differentiation in the conclusions reached by participants of the debate must necessarily fall prey to the approximate nature of this classifica- tion. Daniel Szechi, The Jacobites. Britain and Europe, 1688–1788 (Manchester, 1994), 1–6. -

9 Decorative Pottery at Prestongrange

9 Decorative Pottery at Prestongrange Jane Bonnar This analysis is complemented by the Prestoungrange Virtual Pottery Exhibition to be found on the Internet at http://www.prestoungrange.org PRESTOUNGRANGE UNIVERSITY PRESS http://www.prestoungrange.org FOREWORD This series of books has been specifically developed to provided an authoritative briefing to all who seek to enjoy the Industrial Heritage Museum at the old Prestongrange Colliery site. They are complemented by learning guides for educational leaders. All are available on the Internet at http://www.prestoungrange.org the Baron Court’s website. They have been sponsored by the Baron Court of Prestoungrange which my family and I re-established when I was granted access to the feudal barony in 1998. But the credit for the scholarship involved and their timeous appearance is entirely attributable to the skill with which Annette MacTavish and Jane Bonnar of the Industrial Heritage Museum service found the excellent authors involved and managed the series through from conception to benefit in use with educational groups. The Baron Court is delighted to be able to work with the Industrial Heritage Museum in this way. We thank the authors one and all for a job well done. It is one more practical contribution to the Museum’s role in helping its visitors to lead their lives today and tomorrow with a better understanding of the lives of those who went before us all. For better and for worse, we stand on their shoulders as we view and enjoy our lives today, and as we in turn craft the world of tomorrow for our children. -

A Singular Solace: an Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000

A Singular Solace: An Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000 David William Dutton BA, MTh October 2020 This dissertation is submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Stirling for the degree of Master of Philosophy in History. Division of History and Politics 1 Research Degree Thesis Submission Candidates should prepare their thesis in line with the code of practice. Candidates should complete and submit this form, along with a soft bound copy of their thesis for each examiner, to: Student Services Hub, 2A1 Cottrell Building, or to [email protected]. Candidate’s Full Name: DAVID WILLIAM DUTTON Student ID: 2644948 Thesis Word Count: 49,936 Maximum word limits include appendices but exclude footnotes and bibliographies. Please tick the appropriate box MPhil 50,000 words (approx. 150 pages) PhD 80,000 words (approx. 300 pages) PhD (by publication) 80,000 words (approx. 300 pages) PhD (by practice) 40,000 words (approx. 120 pages) Doctor of Applied Social Research 60,000 words (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Business Administration 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Education 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Midwifery / Nursing / Professional Health Studies 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Diplomacy 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Thesis Title: A Singular Solace: An Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000 Declaration I wish to submit the thesis detailed above in according with the University of Stirling research degree regulations. I declare that the thesis embodies the results of my own research and was composed by me. Where appropriate I have acknowledged the nature and extent of work carried out in collaboration with others included in the thesis. -

LHB37 LOTHIAN HEALTH BOARD Introduction 1 Agenda of Meetings of Lothian Health Board, 1987-1995 2 Agenda of Meetings of Lothia

LHB37 LOTHIAN HEALTH BOARD Introduction 1 Agenda of Meetings of Lothian Health Board, 1987-1995 2 Agenda of Meetings of Lothian Health Board Committees, 1987-1989 2A Minutes of Board, Standing Committees and Sub-Committees, 1973-1986 2B Draft Minutes of Board Meetings, 1991-2001 2C [not used] 2D Area Executive Group Minutes, 1973-1986 2E Area Executive Group Agendas and Papers, 1978-1985 2F Agenda Papers for Contracts Directorate Business Meetings, 1993-1994 2G Agenda Papers of Finance, Manpower and Establishment Committee, 1975-1979 2H Agenda papers of the Policy and Commissioning Team Finance and Corporate Services Sub- Group, 1994-1995 2I [not used] 2J Minutes and Papers of the Research Ethics Sub-Committees, 1993-1995 3 Annual Reports, 1975-2004 4 Annual Reports of Director of Public Health, 1989-2008 5 Year Books, 1977-1992 6 Internal Policy Documents and Reports, 1975-2005 7 Publications, 1960-2002 8 Administrative Papers, 1973-1994 8A Numbered Administrative Files, 1968-1993 8B Numbered Registry Files, 1970-1996 8C Unregistered Files, 1971-1997 8D Files of the Health Emergency Planning Officer, 1978-1993 9 Annual Financial Reviews, 1974-1987 10 Annual Accounts, 1976-1992 10A Requests for a major item of equipment, 1987-1990 LHB37 LOTHIAN HEALTH BOARD 11 Lothian Medical Audit Committee, 1988-1997 12 Records of the Finance Department, 1976-1997 13 Endowment Fund Accounts, 1972-2004 14 Statistical Papers, 1974-1990 15 Scottish Health Service Costs, 1975-1987 16 Focus on Health , 1982-1986 17 Lothian Health News , 1973-2001 18 Press -

Download This PDF: Living East Lothian Spring 2017

PAGE 2 PAGE 7 Healthy beginnings Business is booming Work on East Lothian Community Businesses snap up units at Hospital is well under way new Brewery Park offices PAGE 5 East Lothian PAGE16 Can you give Put your best the gift of time? foot forward Make a real difference Take the first step in your community to a healthier through volunteering lifestyle www.eastlothian.gov.uk SPRING 2017 Living NEWS FROM YOUR COUNCIL Council budget will protect vital services Three per cent increase Centre, £1.1 million for a new Port Seton Sports Hall and an £850,000 upgrade of in council tax as millions Haddington Corn Exchange. committed to schools, Agreement was also given for a five-year, £85 million council housing programme housing and transport coupled with almost £59 million of investment in housing modernisation AST Lothian Council agreed its and extensions. budget last month which includes The council is also making an additional a major investment of £169 million investment of £1.8 million in adult services in capital projects across and a further £300,000 in children’s services. Ethe county. The council’s spending plans are firmly Resources have been allocated for new focused on maintaining high-quality public schools, adult and children’s services, services while managing finances prudently affordable homes and transport in the face of a £2.9 million reduction in the initiatives, including: Revenue Support Grant received from the l around £97 million of investment over Scottish Government – which makes up three years in new, upgraded or expanded the bulk of the council’s income. -

Download Food & Drink Experiences Itinerary

Food and Drink Experiences TRAVEL TRADE Love East Lothian These itinerary ideas focus around great traditional Scottish hospitality, key experiences and meal stops so important to any trip. There is an abundance of coffee and cake havens, quirky venues, award winning bakers, fresh lobster and above all a pride in quality and in using ingredients locally from the fertile farm land and sea. The region boasts Michelin rated restaurants, a whisky distillery, Scotland’s oldest brewery, and several great artisan breweries too. Scotland has a history of gin making and one of the best is local from the NB Distillery. Four East Lothian restaurants celebrate Michelin rated status, The Creel, Dunbar; Osteria, North Berwick; as well as The Bonnie Badger and La Potiniere both in Gullane, recognising East Lothian among the top quality food and drink destinations in Scotland. Group options are well catered for in the region with a variety of welcoming venues from The Marine Hotel in North Berwick to Dunbar Garden Centre to The Prestoungrange Gothenburg pub and brewery in Prestonpans and many other pubs and inns in our towns and villages. visiteastlothian.org TRAVEL TRADE East Lothian Larder - making and tasting Sample some of Scotland’s East Lothian is proudly Scotland’s Markets, Farm Shops Sample our fish and seafood Whisky, Distilleries very best drinks at distilleries Food and Drink County. With a and Delis Our coastal towns all serve fish and and breweries. Glimpse their collection of producers who are chips, and they always taste best by importance in Scotland’s passionate about their products Markets and local farm stores the sea. -

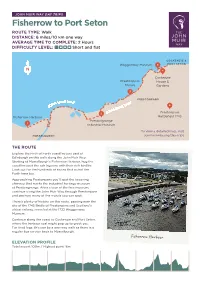

Fisherrow to Port Seton ROUTE TYPE: Walk DISTANCE: 6 Miles/10 Km One Way AVERAGE TIME to COMPLETE: 2 Hours DIFFICULTY LEVEL: Short and Flat

JOHN MUIR WAY DAY TRIPS Fisherrow to Port Seton ROUTE TYPE: Walk DISTANCE: 6 miles/10 km one way AVERAGE TIME TO COMPLETE: 2 Hours DIFFICULTY LEVEL: Short and flat COCKENZIE & Waggonway Museum 5 PORT SETON LONGNIDDRY 4 Cockenzie Prestonpans House & Murals Gardens 3 PRESTONPANS R W M U I AY Y H N A O W 6 J U IR N M OH 2 J Prestonpans Fisherrow Harbour Battlefield 1745 Prestongrange 1 Industrial Museum To view a detailed map, visit MUSSELBURGH joinmuirway.org/day-trips THE ROUTE Explore the Firth of Forth coastline just east of Edinburgh on this walk along the John Muir Way. Starting at Musselburgh’s Fisherrow Harbour, hug the coastline past the ash lagoons with their rich birdlife. Look out for the hundreds of swans that patrol the Forth here too. Approaching Prestonpans you’ll spot the towering chimney that marks the industrial heritage museum at Prestongrange. After a tour of the free museum, continue along the John Muir Way through Prestonpans and see how many of the murals you can spot. There’s plenty of history on this route, passing near the site of the 1745 Battle of Prestonpans and Scotland’s oldest railway, revealed at the 1722 Waggonway Museum. Continue along the coast to Cockenzie and Port Seton, where the harbour seal might pop up to greet you. For tired legs, this can be a one-way walk as there is a regular bus service back to Musselburgh. Fisherrow Harbour ELEVATION PROFILE Total ascent 100m / Highest point 16m JOHN MUIR WAY DAY TRIPS Fisherrow to Port Seton PLACES OF INTEREST 1 FISHERROW HARBOUR Just west of Musselburgh this harbour, built from 1850, is still used by pleasure and fishing boats. -

Prestongrange House

1 Prestongrange House Sonia Baker PRESTOUNGRANGE UNIVERSITY PRESS http://www.prestoungrange.org FOREWORD This series of books has been specifically developed to provided an authoritative briefing to all who seek to enjoy the Industrial Heritage Museum at the old Prestongrange Colliery site. They are complemented by learning guides for educational leaders. All are available on the Internet at http://www.prestoungrange.org the Baron Court’s website. They have been sponsored by the Baron Court of Prestoungrange which my family and I re-established when I was granted access to the feudal barony in 1998. But the credit for the scholarship involved and their timeous appearance is entirely attributable to the skill with which Annette MacTavish and Jane Bonnar of the Industrial Heritage Museum service found the excellent authors involved and managed the series through from conception to benefit in use with educational groups. The Baron Court is delighted to be able to work with the Industrial Heritage Museum in this way. We thank the authors one and all for a job well done. It is one more practical contribution to the Museum’s role in helping its visitors to lead their lives today and tomorrow with a better understanding of the lives of those who went before us all. For better and for worse, we stand on their shoulders as we view and enjoy our lives today, and as we in turn craft the world of tomorrow for our children. As we are enabled through this series to learn about the first millennium of the barony of Prestoungrange we can clearly see what sacrifices were made by those who worked, and how the fortunes of those who ruled rose and fell. -

Prestongrange Museum

Tell us how you feel about …. Prestongrange Museum How to have your say East Lothian Council have commissioned Simpson and Brown Architects as lead consultant to deliver a masterplan for Prestongrange Museum (PGM) to identify a vision for the sustainable future of the site and the options available to achieve this. We are interested in everyone’s views about this, whether people want no change at Prestongrange, or a significant redevelopment of the site. We also want to know how individuals and groups would like to be involved in future. There are seven main ways to have your say between now and January 2018: Respond to the public questionnaire: https://www.surveymonkey.co.uk/r/PGMasterPlanSH Comment on the project Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/Prestongrange-Perspectives-872559646259120/ Contact the study team direct by email or ‘phone through the details below Attend one or more of the public consultation events (dates, time and venues will be posted on the Facebook page and also emailed to anyone requesting the information through responding to the questionnaire or through other means) Ask us to attend a meeting with your group or organisation. We are particularly interested to speak with groups or organisations that use the Prestongrange site at the moment or would like to use the site in future Write to us anonymously at the correspondence address below Feedback your views through your local area partnership http://www.eastlothian.gov.uk/areapartnerships How are we going to use the information? The information we are gathering will be used in drawing up the final masterplan report which is due in March 2018. -

Open Entry Form 2021 V2

Royal Musselburgh Golf Club Ltd. Open Competitions 2021 Details and Entry Form Date: Details: Tick Date: Details: Tick Entry Fee Entry Fee Entry Entry Thursday £30.00 Tuesday Junior Open – Age Max 18 £5.00 Ladies Tri-Am, Max Paying H’cap 36 13th May 2021 per Team 3rd Aug 2021 yrs. Max Playing H’cap 36 per Junior Saturday Gents Open Pairs - 2 Ball better ball £16.00 Tuesday Senior Open Texas Scramble, £40.00 15th May 2021 Maximum Playing H’cap 28 per pair 17th Aug 2021 50+ H’cap Max G28, L36 *1 per Team Tuesday Senior Open Texas Scramble, 50+ £40.00 Saturday Mixed Foursomes Open £15.00 18th May 2021 Max Playing H’cap G28, L36 *1 per Team 4th Sept2021 H’cap G28, L36 per couple Tuesday Senior Mixed Foursomes Open, 55+ £15.00 Wednesday Ladies Better Ball, Max £16.00 per 25th May 2021 Maximum Playing H’cap G28, L36 per couple 8th Sept 2021 Playing H’cap 36 Team Thursday Gents Senior Open, 55+ £15.00 per *1 - teams may be 4 Gents, 4 Ladies or a mixture 24th June 2021 Maximum Playing H’cap 28 Player Monday Ladies Greensomes, Max Playing £8.00 Entries may be made online via BRS through our website at th 28 June 2021 H’cap 36 per Player www.royalmusselburgh.co.uk No refunds will be made for cancellations Gents 18 Hole Scratch – Willie Park Saturday £15.00 per within 7 days of the competition. Putter, H’cap Max 5 and Handicap 31st July 2021 Open, Max Playing H’cap 18 Player Closing Please send completed entry form, Competition Preferred Tee Off Date cheque and SAE [or email address] to:- Ladies Tri-Am 09:30am – 14:30pm 06 May2021 Gents Open Pairs 07:00am – 14:30pm 08 May 2021 Honorary Secretary Snr Open Texas Scramble – May 07:30am – 16:00pm 11 May 2021 Royal Musselburgh Golf Club, Snr Mixed Foursomes Open 09:00am – 13:00pm 18 May 2021 Prestongrange House, Gents Senior Open 07:30am – 16:00pm 17 June 2021 PRESTONPANS, Ladies Greensomes 09:30am – 14:30pm 21 June 2021 EH32 9RP. -

2 Acheson/Morrison's Haven

2 Acheson/Morrison’s Haven What Came and Went and How? Julie Aitken PRESTOUNGRANGE UNIVERSITY PRESS http://www.prestoungrange.org FOREWORD This series of books has been specifically developed to provided an authoritative briefing to all who seek to enjoy the Industrial Heritage Museum at the old Prestongrange Colliery site. They are complemented by learning guides for educational leaders. All are available on the Internet at http://www.prestoungrange.org the Baron Court’s website. They have been sponsored by the Baron Court of Prestoungrange which my family and I re-established when I was granted access to the feudal barony in 1998. But the credit for the scholarship involved and their timeous appearance is entirely attributable to the skill with which Annette MacTavish and Jane Bonnar of the Industrial Heritage Museum service found the excellent authors involved and managed the series through from conception to benefit in use with educational groups. The Baron Court is delighted to be able to work with the Industrial Heritage Museum in this way. We thank the authors one and all for a job well done. It is one more practical contribution to the Museum’s role in helping its visitors to lead their lives today and tomorrow with a better understanding of the lives of those who went before us all. For better and for worse, we stand on their shoulders as we view and enjoy our lives today, and as we in turn craft the world of tomorrow for our children. As we are enabled through this series to learn about the first millennium of the barony of Prestoungrange we can clearly see what sacrifices were made by those who worked, and how the fortunes of those who ruled rose and fell. -

164/14 East Lothian Museums Service

Members’ Library Service Request Form Date of Document 01/08/14 Originator Head Of Communities And Partnerships Originator’s Ref (if any) Document Title East Lothian Council Museums Service Please indicate if access to the document is to be “unrestricted” or “restricted”, with regard to the terms of the Local Government (Access to Information) Act 1985. Unrestricted Restricted If the document is “restricted”, please state on what grounds (click on grey area for drop- down menu): For Publication Please indicate which committee this document should be recorded into (click on grey area for drop-down menu): Cabinet Additional information: Authorised By Monica Patterson Designation Depute Chief Executive Date 01/08/14 For Office Use Only: Library Reference 164/14 Date Received 26/08/14 Bulletin Aug14 REPORT TO: Members’ Library Service MEETING DATE: BY: Head of Communities and Partnerships SUBJECT: East Lothian Council Museums Service 1 PURPOSE 1.1 To advise Members about the updates and revisions to the following East Lothian Council Museums Service Policies as required to meet the requirements of the Museums Accreditation Scheme: Exhibitions Programming Policy and Procedures Environmental Policy Statement 2 RECOMMENDATIONS 2.1 That Members note the content of this report 3 BACKGROUND 3.1 East Lothian Council Museums Service manages Prestongrange Museum, the John Gray Centre Museum and Dunbar Town House Museum and Gallery. The Service also manages John Muir’s Birthplace in Dunbar on behalf of the John Muir Birthplace Trust and supports Musselburgh Museum and Heritage group to operate Musselburgh Museum. Dunbar and District History Society support the operation of Dunbar Town House Museum and Gallery.