Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report on Public Water System Violations Vermont Water Supply Division

Annual Report on Public Water System Violations Vermont Water Supply Division 103 South Main St. Waterbury, VT 05671-0403 (802) 241-3400 or 1-800-823-6500 in Vermont January 1, 2006 - December 31, 2006 July 1, 2007 INTRODUCTION Vermont’s Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) is authorized by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to administer the Public Water Supply System program in the state. DEC’s Water Supply Division implements the program. The division’s primary goal is to ensure that citizens and visitors of the Green Mountain State have drinking water that is safe for human consumption. To maintain the authority to administer the program (also called primacy), the state has to implement and enforce rules that are at least as stringent as the federal drinking water regulations. To comply with federal regulations, DEC promulgated the State’s Water Supply Rule (Chapter 21 of the Environmental Protection Rules) on September 24, 1992. The rule was revised in 1996, 1999, 2002 and again in 2005 to incorporate the 1996 amendments to the federal Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA). The 1996 amendments strengthened many aspects of the SDWA, including government and water system accountability, and public awareness and involvement. The new “Right-to-know” provisions will give citizens the information they need to make their own health decisions, allow increased participation in drinking water decision-making, and promote accountability at the water system, state, and federal levels. One of the “Right-to-know” provisions requires states with primacy to prepare an annual Public Water System Compliance Report. The report must include the name and Water System Identification (WSID) number of each public water system that violated SDWA regulations during the year. -

Mt. Philo State Park Long Range Management Plan Was Conducted in Accordance with Agency of Natural Resources Policies, Procedures, and Guidelines

Rutland Stewardship Team Reuben Allen, Parks Regional Manager Doug Blodgett, Wildlife Biologist (retired) John Lones, State Lands Forester Nick Fortin, Wildlife Biologist Shawn Good, Fisheries Biologist Maria Mayer, Parks Regional Manager (former) Nate McKeen, Forestry District Manager Shannon Pytlik, River Scientist Jessica Savage, Recreation Program Manager Ethan Swift, Watershed Planner Lisa Thornton, State Lands Stewardship Forester Robert Zaino, State Lands Ecologist Mt. Philo State Park – Long Range Management Plan Page ii Mission Statements Vermont Agency of Natural Resources The mission of the Agency of Natural Resources is “to protect, sustain, and enhance Vermont’s natural resources, for the benefit of this and future generations.” Four agency goals address the following: • To promote the sustainable use of Vermont’s natural resources; • To protect and improve the health of Vermont’s people and ecosystems; • To promote sustainable outdoor recreation; and • To operate efficiently and effectively to fulfill our mission. Departments Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation Mission Statement To preserve, enhance, restore, and conserve Vermont’s natural resources, and protect human health, for the benefit of this and future generations. Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department Mission Statement The mission of the Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department is the conservation of all species of fish, wildlife, and plants and their habitats for the people of Vermont. To accomplish this mission, the integrity, diversity, and vitality of their -

Mt. Philo Long Range Manangement Plan 2019

Rutland Stewardship Team Reuben Allen, Parks Regional Manager Doug Blodgett, Wildlife Biologist (retired) John Lones, State Lands Forester Nick Fortin, Wildlife Biologist Shawn Good, Fisheries Biologist Maria Mayer, Parks Regional Manager (former) Nate McKeen, Forestry District Manager Shannon Pytlik, River Scientist Jessica Savage, Recreation Program Manager Ethan Swift, Watershed Planner Lisa Thornton, State Lands Stewardship Forester Robert Zaino, State Lands Ecologist Mt. Philo State Park – Long Range Management Plan Page ii Mission Statements Vermont Agency of Natural Resources The mission of the Agency of Natural Resources is “to protect, sustain, and enhance Vermont’s natural resources, for the benefit of this and future generations.” Four agency goals address the following: • To promote the sustainable use of Vermont’s natural resources; • To protect and improve the health of Vermont’s people and ecosystems; • To promote sustainable outdoor recreation; and • To operate efficiently and effectively to fulfill our mission. Departments Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation Mission Statement To preserve, enhance, restore, and conserve Vermont’s natural resources, and protect human health, for the benefit of this and future generations. Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department Mission Statement The mission of the Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department is the conservation of all species of fish, wildlife, and plants and their habitats for the people of Vermont. To accomplish this mission, the integrity, diversity, and vitality of their -

Federal Register/Vol. 66, No. 219/Tuesday, November 13, 2001

Federal Register / Vol. 66, No. 219 / Tuesday, November 13, 2001 / Notices 56853 after the Environmental Protection comments should be submitted by IDAHO Agency has published a notice of November 28, 2001. Butte County availability of the FEIS in the Federal Carol D. Shull, Arco Baptist Community Church, 402 W. Register. Keeper of the National Register of Historic Grand Ave., Arco, 01001303 FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Places. Latah County Kathleen Przybylski, Voyageurs ALABAMA Hotel Rietmann, 525 and 529 S. Main St., National Park, 3131 Highway 53, Troy, 01001302 International Falls, MN 56649, Autauga County Kenworthy Theatre, (Motion Picture telephone: 218–283–9821. Copies of the Mount Sinai School, (The Rosenwald Theater Buildings in Idaho MPS), 508 S. plan may also be requested at this School Building Fund and Associated Main St., Moscow, 01001305 Buildings MPS), 1820 Cty. Rd. 57, Nu Art Theatre, (Motion Picture Theater address and telephone number, or by e- Buildings in Idaho MPS), 516 S. Main _ Prattville, 01001296 mail from Kathleen [email protected]. St., Moscow, 01001304 Bullock County SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: The Twin Falls County Sardis Baptist Church, AL 223S at jct. Cty. purpose of the general management Twin Falls Original Townsite Residential plan/visitor use and facilities plan is to Rd. 22, Union Springs, 01001299 Historic District, Roughly bounded by set forth the basic management Calhoun County Blue Lakes Ave., Addison Ave., 2nd Ave. philosophy for the park and to provide E, and 2nd Ave. W, Twin Falls, Ten Oaks, 805 Pelham Rd. S, Jacksonville, 01001306 the strategies for addressing issues and 01001298 achieving identified management ILLINOIS objectives. -

Massachusetts Massachusetts Office of Travel and Tourism, 10 Park Plaza, Suite 4510, Boston, MA 02116

dventure Guide to the Champlain & Hudson River Valleys Robert & Patricia Foulke HUNTER PUBLISHING, INC. 130 Campus Drive Edison, NJ 08818-7816 % 732-225-1900 / 800-255-0343 / fax 732-417-1744 E-mail [email protected] IN CANADA: Ulysses Travel Publications 4176 Saint-Denis, Montréal, Québec Canada H2W 2M5 % 514-843-9882 ext. 2232 / fax 514-843-9448 IN THE UNITED KINGDOM: Windsor Books International The Boundary, Wheatley Road, Garsington Oxford, OX44 9EJ England % 01865-361122 / fax 01865-361133 ISBN 1-58843-345-5 © 2003 Patricia and Robert Foulke This and other Hunter travel guides are also available as e-books in a variety of digital formats through our online partners, including Amazon.com, netLibrary.com, BarnesandNoble.com, and eBooks.com. For complete information about the hundreds of other travel guides offered by Hunter Publishing, visit us at: www.hunterpublishing.com All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a re- trieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechani- cal, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. Brief extracts to be included in reviews or articles are permitted. This guide focuses on recreational activities. As all such activities contain ele- ments of risk, the publisher, author, affiliated individuals and companies disclaim any responsibility for any injury, harm, or illness that may occur to anyone through, or by use of, the information in this book. Every effort was made to in- sure the accuracy of information in this book, but the publisher and author do not assume, and hereby disclaim, any liability for loss or damage caused by errors, omissions, misleading information or potential travel problems caused by this guide, even if such errors or omissions result from negligence, accident or any other cause. -

Lake Champlain Bikeways Y

lake champl ain bik town ewa and cou ys chitte ntr nden coun y ty, ver mont six loops of the lake champlain bikeways network in chittenden county, vermont town and country bikeways table of contents • lake champlain bikeways network map 1 • north of the big hills 14 • chittenden county 2 • the lake champlain region at a glance 16 • map legend and climate data 3 • visitor information and bicycle services 17 • little country hills 4 • chittenden county attractions 18 • cycle the city 6 • making connections 19 • covered bridges 8 • safety guidelines 20 • mountain views 10 • about lake champlain bikeways 21 • roads less traveled 12 Disclaimer: Users assume all risks, inherent and not inherent, in the use of materials recommending routes of the Lake Champlain Bikeways network and all affiliated organizations, and individuals disclaim any and all liability on their part for damages or injuries to persons or property should they occur. Routes are chosen, designated and/or signed because: they are popular, or are preferred, or provide continuous routes to destinations, or are lightly traveled, or are scenic, or have more room for cars and bikes, or possess a combination of these attributes. Credits: cover - Burlington Waterfront/Skye Chalmers; inside cover - Pleasant Valley, Underhill/Andre Jenny hamplain bike lake c ways Chambley St. Jean-sur-Richelieu Pedal Power Panoramas (33.2) Ship to Shore (20.4) Mountains of Maple (35.0) Champlain Coast Caper (35.8) Canada Lake Carmi Dairy Circuit (28.6) International Affairs (26.8) United States Missisquoi Valley Rail Trail (26.4) The William H. Miner Story (35.3) Liquid Elixir (11.7) The Climber (38.0) A Trail to Two Beaches (15.8) Over the Hills and Far Away (45.2) A Legacy of Ancient Stone (10.1) The Flatlander (21.1) St. -

Library of Congress Classification

E AMERICA E America General E11-E29 are reserved for works that are actually comprehensive in scope. A book on travel would only occasionally be classified here; the numbers for the United States, Spanish America, etc., would usually accommodate all works, the choice being determined by the main country or region covered 11 Periodicals. Societies. Collections (serial) For international American Conferences see F1404+ Collections (nonserial). Collected works 12 Several authors 13 Individual authors 14 Dictionaries. Gazetteers. Geographic names General works see E18 History 16 Historiography 16.5 Study and teaching Biography 17 Collective Individual, see country, period, etc. 18 General works Including comprehensive works on America 18.5 Chronology, chronological tables, etc. 18.7 Juvenile works 18.75 General special By period Pre-Columbian period see E51+; E103+ 18.82 1492-1810 Cf. E101+ Discovery and exploration of America Cf. E141+ Earliest accounts of America to 1810 18.83 1810-1900 18.85 1901- 19 Pamphlets, addresses, essays, etc. Including radio programs, pageants, etc. 20 Social life and customs. Civilization. Intellectual life 21 Historic monuments (General) 21.5 Antiquities (Non-Indian) 21.7 Historical geography Description and travel. Views Cf. F851 Pacific coast Cf. G419+ Travels around the world and in several parts of the world including America and other countries Cf. G575+ Polar discoveries Earliest to 1606 see E141+ 1607-1810 see E143 27 1811-1950 27.2 1951-1980 27.5 1981- Elements in the population 29.A1 General works 29.A2-Z Individual elements, A-Z 29.A43 Akan 29.A73 Arabs 29.A75 Asians 29.B35 Basques Blacks see E29.N3 29.B75 British 29.C35 Canary Islanders 1 E AMERICA E General Elements in the population Individual elements, A-Z -- Continued 29.C37 Catalans 29.C5 Chinese 29.C73 Creoles 29.C75 Croats 29.C94 Czechs 29.D25 Danube Swabians 29.E37 East Indians 29.E87 Europeans 29.F8 French 29.G26 Galicians (Spain) 29.G3 Germans 29.H9 Huguenots 29.I74 Irish 29.I8 Italians 29.J3 Japanese 29.J5 Jews 29.K67 Koreans 29.N3 Negroes. -

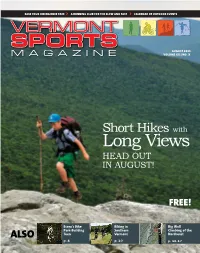

Long Views Head out in August!

Ease your hikiNg kNee pAiN A runniNg club for the slow and fAst CaleNdAr of outdoor eVeNts VERMONT SPORTS August 2011 MAGAZINE Volume XX | No. X Short Hikes with Long Views HEAD OUT IN AUGUST! free! Essex's Bike Biking in Big Wall Park-Building Southern Climbing of the ALSO Teen Vermont FREENortheast ! p. 8 p. 10 p. 16-17 © Wolverine Outdoors 2011 Wolverine © BOGL Every day brings new adventure. That’s why versatility is key to everything Merrell does. Take our Barefoot Trail Glove. This innovative, minimalist design gets you closer to the ground to liberate and strengthen your feet. With its traction and minimal cushioning, you’ve got unlimited access to any terrain you choose. The Merrell Barefoot collection. Let Your Feet Lead You. Find out how and download our free app at merrell.com/barefoot depArtmeNts coNteNts 4 From Vermont sports The Outdoors for Everyone southerN comfort 3 ways to cycle through the seasons at Vermont’s 5 Sign in 10 News, Views, and Ideas © Wolverine Outdoors 2011 Wolverine © lower latitudes From the Outdoor Community Easy hikes ArouNd Lake chAmplAiN 6 Sports medicine 12–15 you don’t have to be a 46er to master these treks Help Your Knees Enjoy the Hike Too the East’s big Walls 7 Muscles Not motors Bamboo Bottle, 16–17 A climber’s guide to the Northeast’s tallest cliffs Kayak Lift Assist, Bike Taillight whAt’s New and improVed iN 8 18 & under 18 climbiNg geAr Teen Tackles Zoning we break down the latest from ropes to b allNutz Permits, Fundraising to Build Public Bike Park in Essex the greeN mouNtAiN Athletic AssociAtioN— 20–21 Reader Athletes 19 Not Just for speed DaemoNs Keely Punger club hopes to encourage New, improving runners David Metraux 22–24 Calendar of outdoor commuNity rowiNg Events 28 boaters meet for fitness and friendship 23 Vermont Sports Business directory 25 Retail Junkie superstar M-M-M-M-My Petunia 27 Out and About Sports Fans: The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly Photo by Sky Barsch Gleiner Photo by Sky on the cover: Aidan Casner of Montpelier ascends the Sunset Ridge Trail on Mount Mansfield in Underhill. -

Fy19 Anr Pilot Report ]

FY19 ANR PILOT REPORT ] B E G H I L V FAIR ID MARKET 1 TOWN OF DEPARTMENT OF NUMBER PROPERTY DESCRIPTION ACRES VALUE FY19 PILOT 2 Addison Forests, Parks & Recreation FP1 Chimney Point State Park 53.40 $ 270,100 $2,075.57 3 Addison Forests, Parks & Recreation FP2 DAR State Park RT 17 95.53 $ 453,800 $3,535.38 4 Addison Fish and Wildlife FW1 Snake Mtn. WMA SE Boundary 350.25 $ 454,100 $3,094.05 5 Addison Fish and Wildlife FW2 Dead Creek WMA - Main Block 2,395.60 $ 2,856,500 $17,663.81 6 Addison Fish and Wildlife FW3 Dead Creek WMA - Jct. TH 4 & 20 3.73 $ 46,500 $340.32 7 Addison Fish and Wildlife FW4 McCuen Slang WMA RT 125 53.00 $ 91,700 $722.48 8 Addison Fish and Wildlife FW5 Whitney/Hospital Creek WMA 103.53 $ 135,700 $1,057.41 9 Addison Fish and Wildlife FW6 Snake Mtn. WMA Parking Lot-on TH 22 0.15 $ 22,900 $178.79 10 Addison Fish and Wildlife FW7 Snake Mtn. WMA Parking Lot - on TH 28 0.23 $ 25,300 $195.20 11 Addison Fish and Wildlife FW8 Dead Creek WMA - End of TH 20 91.38 $ 150,400 $1,113.87 12 Addison Fish and Wildlife FW9 Dead Creek WMA 5.02 $ 5,800 $35.54 13 Addison Fish and Wildlife FW10 WHC WMA - WHITNEY CREEK 210.20 $ 136,700 $975.47 14 Addison Fish and Wildlife FW11 Dead Creek WMA - Dubois 40.00 $ 37,327 $147.55 15 Addison Temporary Buffer Buffer Payment $1,500.00 16 Addison Total 3,402.02 $ 4,686,827 $32,635.41 FY19 ANR PILOT REPORT ] B E G H I L V FAIR ID MARKET 1 TOWN OF DEPARTMENT OF NUMBER PROPERTY DESCRIPTION ACRES VALUE FY19 PILOT Black River Streambank - 70.9 ac. -

H.885: Current Year ANR Pilot Detail for 2013 (FY2014)

TAXYEAR TNAME DEPT PROPLOC ACRES PARCELS FMV_CURRENT 2013 CUV Total PILOT Payment 2013 Addison FP Chimney Point State Park 53.4 1 337,300 $0 $ 3,373.00 2013 Addison FP DAR State Park RT 17 95.53 1 585,600 $0 $ 5,856.00 2013 Addison FW Snake Mtn. WMA SE Boundary 350.25 2 412,000 $0 $ 4,120.00 2013 Addison FW Dead Creek WMA - Main Block 2395.6 3 1,886,100 $0 $ 18,861.00 2013 Addison FW Dead Creek WMA - Jct. TH 4 & 20 3.73 1 51,400 $0 $ 514.00 2013 Addison FW McCuen Slang WMA RT 125 53 1 121,500 $0 $ 1,215.00 2013 Addison FW Whitney/Hospital Creek WMA 103.53 1 175,200 $0 $ 1,752.00 2013 Addison FW Snake Mtn. WMA Parking Lot-on TH 22 0.15 1 29,700 $0 $ 297.00 2013 Addison FW Snake Mtn. WMA Parking Lot - on TH 28 0.23 1 31,900 $0 $ 319.00 2013 Addison FW Dead Creek WMA - End of TH 20 91.38 1 171,400 $0 $ 1,714.00 2013 Addison FW Dead Creek WMA 5.02 3 3,700 $0 $ 37.00 2013 Addison FW WHC WMA - WHITNEY CREEK 210.2 3 141,300 $0 $ 1,413.00 2013 Albany FW Black River Streambank - 70.9 ac. river lot south side RT 14/6.73 ac. SB north side RT 14 77.63 1 58,600 $0 $ 586.00 2013 Alburgh FP Alburg Dunes State Park 646.9 1 1,675,200 $0 $ 16,752.00 2013 Alburgh FP Alburg Dunes State Park 4 1 29,300 $0 $ 293.00 2013 Alburgh FW Mud Creek WMA Wetland 1078.99 3 687,700 $0 $ 6,877.00 2013 Alburgh FW Lake Champlain Access 2.08 1 176,400 $0 $ 1,764.00 2013 Alburgh FW Dillenbeck Bay Access 1.08 1 71,800 $0 $ 718.00 2013 Alburgh FW Kelly Bay Access 1.98 1 89,500 $0 $ 895.00 2013 Alburgh FW Mud Creek WMA/Wetland 72.5 3 24,100 $0 $ 241.00 2013 Alburgh FW MUD CREEK -

National Register of Historic Places 2001 Weekly Lists

National Register of Historic Places 2001 Weekly Lists WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 12/26/00 THROUGH 12/29/00 .................................... 3 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 1/02/01 THROUGH 1/05/01 ........................................ 7 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 1/08/01 THROUGH 1/12/01 ...................................... 12 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 1/16/01 THROUGH 1/19/01 ...................................... 15 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 1/22/01 THROUGH 1/26/01 ...................................... 19 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 1/29/01 THROUGH 2/02/01 ...................................... 24 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 2/05/01 THROUGH 2/09/01 ...................................... 27 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 2/12/01 THROUGH 2/16/01 ...................................... 31 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 2/19/01 THROUGH 2/23/01 ...................................... 34 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 2/26/01 THROUGH 3/02/01 ...................................... 36 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 3/05/01 THROUGH 3/09/01 ...................................... 40 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 3/12/01 THROUGH 3/16/01 ...................................... 43 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 3/19/01 THROUGH 3/23/01 ...................................... 47 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 3/26/01 THROUGH 3/30/01 ...................................... 49 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 4/02/01 THROUGH 4/06/01 ...................................... 53 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 4/09/01 THROUGH 4/13/01 ...................................... 55 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 4/16/01 THROUGH 4/20/01 ..................................... -

Ediacaran–Ordovician of East Laurentia— S

EDIACARAN–ORDOVICIAN OF EAST LAURENTIA— S. W. FORD MEMORIAL VOLUME THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK Regents of The University ROBERT M. BENNETT, Chancellor, B.A., M.S. .......................................................................................................... Tonawanda MERRYL H. TISCH, Vice Chancellor, B.A., M.A. Ed.D. ........................................................................................... New York SAUL B. COHEN, B.A., M.A., Ph.D. ........................................................................................................................ New Rochelle JAMES C. DAWSON, A.A., B.A., M.S., Ph.D. ........................................................................................................... Peru ANTHONY S. BOTTAR, B.A., J.D. .............................................................................................................................. Syracuse GERALDINE D. CHAPEY, B.A., M.A., Ed.D. ............................................................................................................ Belle Harbor ARNOLD B. GARDNER, B.A., LL.B. .......................................................................................................................... Buffalo HARRY PHILLIPS, 3rd, B.A., M.S.F.S. ....................................................................................................................... Hartsdale JOSEPH E. BOWMAN,JR., B.A., M.L.S., M.A., M.Ed., Ed.D. ................................................................................. Albany