"Clue Searching: an Aid to Comprehension," by Jay Paul

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

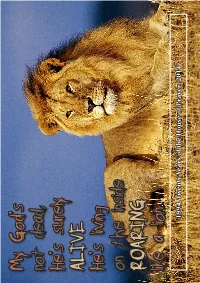

My God's Not Dead, He's Surely Alive He's Living on the Inside Roaring

My God’s not dead, He’s surely ALIVE He’s living on the inside ROARING like a lion 1994 Twenty Years of the House of Prayer 2014 - God’s not Dead Syria Jesus abandoned the changes that have The news this month We have included a taken place in Ireland has been dominated piece from a blog we in recent years and how by the wars in Palestine came across from a our society is becoming and Israel and in Syria monastery in County more Godless than ever and Iraq. We have been Meath. The prior was before. E horrified by images from told of an auction taking Twenty Years Syria of Christians, men, place near the monastery Our theme of twenty women and children, which included some years of the House of D being beheaded and religious artefacts. On Prayer also continues crucified because they going to investigate, he with two articles. One refuse to abandon was horrified to find that reflects on the early days I their faith and convert there was a tabernacle here in the House and to Islam. Harrowing with two Hosts still another talks about the images have been inside! music and how the Music T beamed across the world God’s Not Dead Ministry has evolved of children, beheaded, A couple of articles this over the years in to what maimed and their heads month are on the theme is now SonLight. O put on sticks for all to of ‘God’s Not Dead.’ Ballad of a Viral Video see. This is nothing We recently watched a A servant recounts short of barbaric!! It film of this title here at her thoughts on the R greatly upset me to see the House of Prayer and viral video of Fr. -

(Leviticus 10:6): on Mourning and Refraining from Mourning in the Bible

1 “Do not bare your heads and do not rend your clothes” (Leviticus 10:6): On Mourning and Refraining from Mourning in the Bible Yael Shemesh, Bar Ilan University Many agree today that objective research devoid of a personal dimension is a chimera. As noted by Fewell (1987:77), the very choice of a research topic is influenced by subjective factors. Until October 2008, mourning in the Bible and the ways in which people deal with bereavement had never been one of my particular fields of interest and my various plans for scholarly research did not include that topic. Then, on October 4, 2008, the Sabbath of Penitence (the Sabbath before the Day of Atonement), my beloved father succumbed to cancer. When we returned home after the funeral, close family friends brought us the first meal that we mourners ate in our new status, in accordance with Jewish custom, as my mother, my three brothers, my father’s sisters, and I began “sitting shivah”—observing the week of mourning and receiving the comforters who visited my parent’s house. The shivah for my father’s death was abbreviated to only three full days, rather than the customary week, also in keeping with custom, because Yom Kippur, which fell only four days after my father’s death, truncated the initial period of mourning. Before my bereavement I had always imagined that sitting shivah and conversing with those who came to console me, when I was so deep in my grief, would be more than I could bear emotionally and thought that I would prefer for people to leave me alone, alone with my pain. -

The Bible in Music

The Bible in Music 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb i 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb iiii 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM The Bible in Music A Dictionary of Songs, Works, and More Siobhán Dowling Long John F. A. Sawyer ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb iiiiii 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB Copyright © 2015 by Siobhán Dowling Long and John F. A. Sawyer All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dowling Long, Siobhán. The Bible in music : a dictionary of songs, works, and more / Siobhán Dowling Long, John F. A. Sawyer. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8108-8451-9 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-8452-6 (ebook) 1. Bible in music—Dictionaries. 2. Bible—Songs and music–Dictionaries. I. Sawyer, John F. A. II. Title. ML102.C5L66 2015 781.5'9–dc23 2015012867 ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. -

Church of Saint Edward the Confessor

Pastor: Church of MSGR. PAUL P. ENKE Saint Edward the Confessor Deacon: REV. MR. JOHN BARBOUR 785 NEWARK-GRANVILLE ROAD • GRANVILLE, OHIO 43023 PastorAL MINISTEr/r.C.I.A. WWW.SAINTEDWARDS.ORG PArISH School of rELIgion: 740-587-4160 MIKE MILLISOR [email protected] SARAH SWEEN [email protected] PArISH Office: 740-587-3254 [email protected] Office ManagEr: CHEryL BOGGESS, CPA [email protected] Office Staff: BARBARA HINTERSCHIED [email protected] ANNE ARNOLD [email protected] Youth MINISTEr: MarIssa EVERHart, 740-587-3254 [email protected] Preschool DIrector: ADRIENNE EVANS, 740-587-3275 [email protected] Maintenance: DIANE KINNEY, KEVIN KINNEY FLOYD LAHMON DIrector of Music: PAUL RADKOWSKI, 740-587-3254 [email protected] Baptismal CLASS: (Contact PArISH Office) PatrICIA BELHORN, 740-587-3254 MArrIAgE Preparation INventorY PrOgrAM DCN. JOHN AND CINDY BARBOUR, 740-587-3254 respect LIFE Committee: JOHN KOENIG, 740-587-0720 [email protected] PArISH Council: JOHN MartIN, 614-403-0567 Dominican Sisters of Peace [email protected] visits to SHUT-ins: CONFESSIONS: DIANE KINNEY, 740-587-4121 MASS SCHEDULE SUNDAY MASS SCHEDULE: SATURDAY: 4:00-4:30 P.M. Eucharistic ADOration: SATURDAY: 5:00 P.M. BULLETIN DEADLINE: KIM CHUPKA, 740-587-7067 SUNDAY: 8:15 A.M. Monday NOON [email protected] 10:45 A.M. PARISH OFFICE: KNIghts of Columbus: HOLY DAY MASS SCHEDULE: 740-587-3254 MIKE MaurER, 740-348-6377 [email protected] TBA IN BULLETIN FAX: WEEKDAY MASS SCHEDULE: Prayer CHAIN 740-587-0149 E-MAIL: CIndy KEndrICK, 740-366-2871 MONDAY-FRIDAY: [email protected] 9:00 A.M. -

Amigaos 3.2 FAQ 47.1 (09.04.2021) English

$VER: AmigaOS 3.2 FAQ 47.1 (09.04.2021) English Please note: This file contains a list of frequently asked questions along with answers, sorted by topics. Before trying to contact support, please read through this FAQ to determine whether or not it answers your question(s). Whilst this FAQ is focused on AmigaOS 3.2, it contains information regarding previous AmigaOS versions. Index of topics covered in this FAQ: 1. Installation 1.1 * What are the minimum hardware requirements for AmigaOS 3.2? 1.2 * Why won't AmigaOS 3.2 boot with 512 KB of RAM? 1.3 * Ok, I get it; 512 KB is not enough anymore, but can I get my way with less than 2 MB of RAM? 1.4 * How can I verify whether I correctly installed AmigaOS 3.2? 1.5 * Do you have any tips that can help me with 3.2 using my current hardware and software combination? 1.6 * The Help subsystem fails, it seems it is not available anymore. What happened? 1.7 * What are GlowIcons? Should I choose to install them? 1.8 * How can I verify the integrity of my AmigaOS 3.2 CD-ROM? 1.9 * My Greek/Russian/Polish/Turkish fonts are not being properly displayed. How can I fix this? 1.10 * When I boot from my AmigaOS 3.2 CD-ROM, I am being welcomed to the "AmigaOS Preinstallation Environment". What does this mean? 1.11 * What is the optimal ADF images/floppy disk ordering for a full AmigaOS 3.2 installation? 1.12 * LoadModule fails for some unknown reason when trying to update my ROM modules. -

Chapter 1. Origins of Mac OS X

1 Chapter 1. Origins of Mac OS X "Most ideas come from previous ideas." Alan Curtis Kay The Mac OS X operating system represents a rather successful coming together of paradigms, ideologies, and technologies that have often resisted each other in the past. A good example is the cordial relationship that exists between the command-line and graphical interfaces in Mac OS X. The system is a result of the trials and tribulations of Apple and NeXT, as well as their user and developer communities. Mac OS X exemplifies how a capable system can result from the direct or indirect efforts of corporations, academic and research communities, the Open Source and Free Software movements, and, of course, individuals. Apple has been around since 1976, and many accounts of its history have been told. If the story of Apple as a company is fascinating, so is the technical history of Apple's operating systems. In this chapter,[1] we will trace the history of Mac OS X, discussing several technologies whose confluence eventually led to the modern-day Apple operating system. [1] This book's accompanying web site (www.osxbook.com) provides a more detailed technical history of all of Apple's operating systems. 1 2 2 1 1.1. Apple's Quest for the[2] Operating System [2] Whereas the word "the" is used here to designate prominence and desirability, it is an interesting coincidence that "THE" was the name of a multiprogramming system described by Edsger W. Dijkstra in a 1968 paper. It was March 1988. The Macintosh had been around for four years. -

Dualbooting Amigaos 4 and Amigaos 3.5/3.9

Dualbooting AmigaOS 4 and AmigaOS 3.5/3.9 By Christoph Gutjahr. Licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License This tutorial explains how to turn a classic Amiga into a dualboot system that lets you choose the desired operating system - AmigaOS 4 or AmigaOS 3.5/3.9 - at every cold start. A "cold start" happens when... 1. the computer has just been switched on 2. you press the key combination Control-Amiga-Amiga for more than ten seconds while running AmigaOS 3 3. you press Control-Alt-Alt (instead of Control-Amiga-Amiga) under AmigaOS 4 During a "warm reboot" (e.g. by shortly pressing Control-Amiga-Amiga), the operating system that is currently used will be booted again. Requirements This tutorial is only useful for people using AmigaOS 3.5 or 3.9 in addition to AmigaOS 4. If you're using an older version of OS 3, you can not use the scripts described below. The Amiga in question should have two boot partitions - one for AmigaOS 4 and one for AmigaOS 3.5/3.9, both should be below the famous 4 GB barrier. The OS 4 partition must have a higher boot priority. Two different solutions There are two different approaches for dualbooting: the first one described below will display a simple 'boot menu' at every cold boot, asking the user to select the OS he wants to boot. The other solution explained afterwards will always boot into AmigaOS 4, unless the user enters the "Early Startup Menu" and selects the OS 3 partition as the boot drive. -

William Schwenck Gilbert - Poems

Classic Poetry Series William Schwenck Gilbert - poems - Publication Date: 2004 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive William Schwenck Gilbert(1836 - 1911) William Schwenck Gilbert, born in London in 1836, was the son of a retired naval surgeon. Except for a kidnapping by Italian brigands in Italy at age two, and a ransomed release, he appears to have had a very normal upbringing. Beyond ordinary schooling, he took training as an artillery officer and was tutored in military science with hopes of participating in the Crimean War. Unfortunately for him, but not for us, he did not graduate until after the War was over. Gilbert subsequently joined the militia and was a member for 20 years. After finishing his military training Gilbert worked in a government bureau job which he hated. Upon receiving a nice inheritance from an aunt, Gilbert indulged his fancy and became a barrister. Called to the bar at age 28, Gilbert's law career, with no "rich attorney's elderly, ugly daughter" to help him escape mediocrity, lasted just a few years. Before leaving his law practice, however, he married the daughter of an army officer. Gilbert had shown a proclivity for caustic wit and sarcasm from an early age and it was this talent that put him on the path to greatness. Beginning in 1861, Gilbert contributed dramatic criticism and humorous verse (unsigned) to the popular British magazine FUN. Some of his work was accompanied by cartoons and sketches which were signed "Bab." Many of the characters in the G&S operas were modelled after some of Gilbert's "Bab" characters. -

G:\Collection of Psalms and Hymns

Modernized text Collection of Psalms and Hymns (1743)1 [2nd edn. of 1741] [Baker list, #44] Editorial Introduction: The second edition of CPH (1741) was a major revision of the work. John removed sixty of the psalms and hymns in the first edition to make room for thirty-seven new psalms. Almost all of these new psalms are found in Charles Wesley’s manuscript collections, confirming his authorship. As an indication of Charles’s larger role in this edition, his name was added to the title page. These new psalms are indicated by red font in the Table of Contents below, including two that had been published previously in other collections (shown in blue font). Editions: John Wesley. Collection of Psalms and Hymns. London: Strahan, 1741. John & Charles Wesley. Collection of Psalms and Hymns. 2nd edn., enlarged. London: Strahan, 1743. 3rd London: Strahan, 1744. 4th Bristol: Farley, 1748. 5th London: Cock, 1751. 6th London, 1756. 5th Bristol: Grabham, 1760. 6th Bristol: Pine, 1762. 7th Bristol: Pine, 1765. 8th Bristol: Pine, 1771. 8th Bristol: Pine, 1773. 9th London: Hawes, 1776. 10th London: Hawes, 1779. 11th London: New Chapel, 1789. Note: John Wesley’s personal copy of the 5th edn. (1751), bearing the inscription “J.W. 1756”, is part of the remnants of his personal library at Wesley’s House, London (shelfmark K27). In this copy there are a few manuscript corrections of Charles’s original wording, which are noted in footnotes below. These suggestions were never incorporated into later printed editions of CPH (1741). 1This document was produced by the Duke Center for Studies in the Wesleyan Tradition under editorial direction of Randy L. -

Vbcc Compiler System

vbcc compiler system Volker Barthelmann i Table of Contents 1 General :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 1 1.1 Introduction ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 1 1.2 Legal :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 1 1.3 Installation :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 2 1.3.1 Installing for Unix::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 3 1.3.2 Installing for DOS/Windows::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 3 1.3.3 Installing for AmigaOS :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 3 1.4 Tutorial :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 5 2 The Frontend ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 7 2.1 Usage :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 7 2.2 Configuration :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 8 3 The Compiler :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 11 3.1 General Compiler Options::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 11 3.2 Errors and Warnings :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 15 3.3 Data Types ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 15 3.4 Optimizations::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 16 3.4.1 Register Allocation ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 18 3.4.2 Flow Optimizations :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 18 3.4.3 Common Subexpression Elimination :::::::::::::::::::::: 19 3.4.4 Copy Propagation :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 20 3.4.5 Constant Propagation :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 20 3.4.6 Dead Code Elimination::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 21 3.4.7 Loop-Invariant Code Motion -

Vasm Assembler System

vasm assembler system Volker Barthelmann, Frank Wille June 2021 i Table of Contents 1 General :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 1 1.1 Introduction ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 1 1.2 Legal :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 1 1.3 Installation :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 1 2 The Assembler :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 3 2.1 General Assembler Options ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 3 2.2 Expressions :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 5 2.3 Symbols ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 7 2.4 Predefined Symbols :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 7 2.5 Include Files ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 8 2.6 Macros::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 8 2.7 Structures:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 8 2.8 Conditional Assembly :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 8 2.9 Known Problems ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 9 2.10 Credits ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 9 2.11 Error Messages :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 10 3 Standard Syntax Module ::::::::::::::::::::: 13 3.1 Legal ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 13 3.2 Additional options for this module :::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 13 3.3 General Syntax ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 13 3.4 Directives ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 14 3.5 Known Problems:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: -

Results 2020

Results 2020 A programme of Implemented by Results Brochure 1 Introduction 3 Green City Watch – Taking nature online 26 – Energy decision made easy The start-up journey 4 Greenventory 27 Finding your competitive edge with Copernicus ieco.io – Optimising photovoltaic installations 28 A bit about our start-ups 6 IMMOSensing – Democratising he 2020 edition of the Copernicus Accelerator has officially sustainable solutions in support of modern agriculture. To do so, they Meet the Start-ups 8 the real estate market 29 come to an end. Looking back on the numerous mentoring utilised Copernicus data, as well as meteorological and crop intelligence. 3D EMS – AIntelligent golf course LENKÉ – Space and water solutions sessions, business pivots and client meetings, we must credit executive management 9 empowering communities 30 T the hard work put in by the mentors and entrepreneurs to support Overall, the start-ups benefitted from this coaching activity in their future ajuma – UV-bodyguard 10 MEOSS – Geospatial solutions the implementation of the Accelerator, in particular under the current business development and they regarded it as a catalyst in their growth. for smart territories 31 Audili – Remote topsoil analysis 11 circumstances. The Opening Bootcamp held in December 2019 in Helsinki offered AutoPlan – Making architects’ Nebula42 – Transparency a nurturing environment, equipping start-ups with tools that would for emissions reporting lives easier 12 32 The Accelerator helps young start-ups to use Copernicus data assist them over the following 12 months to take their ideas and information to develop innovative products and ser- to the next level. The activity closed with the virtual Blokgarden – Urban farming as a service 13 OGOR – Efficient monitoring of agricultural land 33 vices for a wide range of sectors.