Acid-Base Equilibria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acidity, Basicity, and Pka 8 Connections

Acidity, basicity, and pKa 8 Connections Building on: Arriving at: Looking forward to: • Conjugation and molecular stability • Why some molecules are acidic and • Acid and base catalysis in carbonyl ch7 others basic reactions ch12 & ch14 • Curly arrows represent delocalization • Why some acids are strong and others • The role of catalysts in organic and mechanisms ch5 weak mechanisms ch13 • How orbitals overlap to form • Why some bases are strong and others • Making reactions selective using conjugated systems ch4 weak acids and bases ch24 • Estimating acidity and basicity using pH and pKa • Structure and equilibria in proton- transfer reactions • Which protons in more complex molecules are more acidic • Which lone pairs in more complex molecules are more basic • Quantitative acid/base ideas affecting reactions and solubility • Effects of quantitative acid/base ideas on medicine design Note from the authors to all readers This chapter contains physical data and mathematical material that some readers may find daunting. Organic chemistry students come from many different backgrounds since organic chemistry occu- pies a middle ground between the physical and the biological sciences. We hope that those from a more physical background will enjoy the material as it is. If you are one of those, you should work your way through the entire chapter. If you come from a more biological background, especially if you have done little maths at school, you may lose the essence of the chapter in a struggle to under- stand the equations. We have therefore picked out the more mathematical parts in boxes and you should abandon these parts if you find them too alien. -

Choosing Buffers Based on Pka in Many Experiments, We Need a Buffer That Maintains the Solution at a Specific Ph. We May Need An

Choosing buffers based on pKa In many experiments, we need a buffer that maintains the solution at a specific pH. We may need an acidic or a basic buffer, depending on the experiment. The Henderson-Hasselbalch equation can help us choose a buffer that has the pH we want. pH = pKa + log([conj. base]/[conj. acid]) With equal amounts of conjugate acid and base (preferred so buffers can resist base and acid equally), then … pH = pKa + log(1) = pKa + 0 = pKa So choose conjugates with a pKa closest to our target pH. Chemistry 103 Spring 2011 Example: You need a buffer with pH of 7.80. Which conjugate acid-base pair should you use, and what is the molar ratio of its components? 2 Chemistry 103 Spring 2011 Practice: Choose the best conjugate acid-base pair for preparing a buffer with pH 5.00. What is the molar ratio of the buffer components? 3 Chemistry 103 Spring 2011 buffer capacity: the amount of strong acid or strong base that can be added to a buffer without changing its pH by more than 1 unit; essentially the number of moles of strong acid or strong base that uses up all of the buffer’s conjugate base or conjugate acid. Example: What is the capacity of the buffer solution prepared with 0.15 mol lactic acid -4 CH3CHOHCOOH (HA, Ka = 1.0 x 10 ) and 0.20 mol sodium lactate NaCH3CHOHCOO (NaA) and enough water to make 1.00 L of solution? (from previous lecture notes) 4 Chemistry 103 Spring 2011 Review of equivalence point equivalence point: moles of H+ = moles of OH- (moles of acid = moles of base, only when the acid has only one acidic proton and the base has only one hydroxide ion). -

The Strongest Acid Christopher A

Chemistry in New Zealand October 2011 The Strongest Acid Christopher A. Reed Department of Chemistry, University of California, Riverside, California 92521, USA Article (e-mail: [email protected]) About the Author Chris Reed was born a kiwi to English parents in Auckland in 1947. He attended Dilworth School from 1956 to 1964 where his interest in chemistry was un- doubtedly stimulated by being entrusted with a key to the high school chemical stockroom. Nighttime experiments with white phosphorus led to the Headmaster administering six of the best. He obtained his BSc (1967), MSc (1st Class Hons., 1968) and PhD (1971) from The University of Auckland, doing thesis research on iridium organotransition metal chemistry with Professor Warren R. Roper FRS. This was followed by two years of postdoctoral study at Stanford Univer- sity with Professor James P. Collman working on picket fence porphyrin models for haemoglobin. In 1973 he joined the faculty of the University of Southern California, becoming Professor in 1979. After 25 years at USC, he moved to his present position of Distinguished Professor of Chemistry at UC-Riverside to build the Centre for s and p Block Chemistry. His present research interests focus on weakly coordinating anions, weakly coordinated ligands, acids, si- lylium ion chemistry, cationic catalysis and reactive cations across the periodic table. His earlier work included extensive studies in metalloporphyrin chemistry, models for dioxygen-binding copper proteins, spin-spin coupling phenomena including paramagnetic metal to ligand radical coupling, a Magnetochemi- cal alternative to the Spectrochemical Series, fullerene redox chemistry, fullerene-porphyrin supramolecular chemistry and metal-organic framework solids (MOFs). -

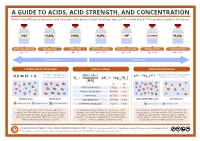

A Guide to Acids, Acid Strength, and Concentration

A GUIDE TO ACIDS, ACID STRENGTH, AND CONCENTRATION What’s the difference between acid strength and concentration? And how does pH fit in with these? This graphic explains the basics. CH COOH HCl H2SO4 HNO3 H3PO4 HF 3 H2CO3 HYDROCHLORIC ACID SULFURIC ACID NITRIC ACID PHOSPHORIC ACID HYDROFLUORIC ACID ETHANOIC ACID CARBONIC ACID pKa = –7 pKa = –2 pKa = –2 pKa = 2.12 pKa = 3.45 pKa = 4.76 pKa = 6.37 STRONGER ACIDS WEAKER ACIDS STRONG ACIDS VS. WEAK ACIDS ACIDS, Ka AND pKa CONCENTRATION AND pH + – The H+ ion is transferred to a + A decrease of one on the pH scale represents + [H+] [A–] pH = –log10[H ] a tenfold increase in H+ concentration. HA H + A water molecule, forming H3O Ka = pKa = –log10[Ka] – [HA] – – + + A + + A– + A + A H + H H H H A H + H H H A Ka pK H – + – H a A H A A – + A– A + H A– H A– VERY STRONG ACID >0.1 <1 A– + H A + + + – H H A H A H H H + A – + – H A– A H A A– –3 FAIRLY STRONG ACID 10 –0.1 1–3 – – + A A + H – – + – H + H A A H A A A H H + A A– + H A– H H WEAK ACID 10–5–10–3 3–5 STRONG ACID WEAK ACID VERY WEAK ACID 10–15–10–5 5–15 CONCENTRATED ACID DILUTE ACID + – H Hydrogen ions A Negative ions H A Acid molecules EXTREMELY WEAK ACID <10–15 >15 H+ Hydrogen ions A– Negative ions Acids react with water when they are added to it, The acid dissociation constant, Ka, is a measure of the Concentration is distinct from strength. -

Acid-Base Interactions in Wetting

J. rldlresiortSci. Tetltttol. \irl. -5.No. l. pp.57-69 ( l99l ) o VsP t9el. Acid-baseinteractions in wetting GEORGE M. WHITESIDES,*HANS A. BIEBUYCK.JOHN P.FOLKERS andKEVIN L. PRIME Departntent of Chentistry,Harvard Universiry',Cambridge, hlA 02138,USA Revisedversion received 27 Aueust1990 Abstract-The studv of the ionizationof carboxylicacid groups at the interfacebetween organic solidsand water demonstratesbroad similaritiesto the ionizationsof thesegroups in homogeneous aqueoussolution, but with importantsystematic differences. Creation of a chargedgroup from a neutralone by protonationor deprotonation(whether -NHr* from -NH, or -CO; from -CO,H) at the interfacebetu'een surface-functionalized polyethylene and \r'ateris more difficult than that in homogeneousaqueous solution. This differenceis probably related to the low effectivedielectric constantof the interface(5=9) relativeto water (e=80). It is not known to what extentthis differencein e (and in other propertiesof the interphase,considered as a thin solventphase) is reflectedin the stabilityof the organicions relativeto their neutral forms in the interphaseand in - solution,and to whatextent in differencesin the concentrationof H' and OH in the interphaseand in solution.Self-assembled monolayers (SAMs)-especially of terminallyfunctionalized alkanethiols (HS(CH:),,X) adsorbedon gold-provide model systemswith relativelywell-ordered structures thar are useful in establishingthe fundamentalsof ionizationof protic acidsand basesat the interface betr"'eenorganic solids and water.These systems,coupled r.r'ithnew analyticalmethods such as photoacousticcalorimetry (PAC) and contact angletitration, may make it possibleto disentangle some of the complex puzzlespresented by proton-transferreactions in the environmentof the organicsolid-* ater interphase. Keyx'ords:Contact ansle titration; photoacoustic calorimetrv: poly'ethylene carboxylic acid: contact angle:polvmer surfaces; u'etting; self-assembled monolavers. -

Hydride Abstraction and Deprotonation – an Efficient Route to Low Co-Ordinate Phosphorus and Arsenic Species

Hydride Abstraction and Deprotonation – an Efficient Route to Low Co-ordinate Phosphorus and Arsenic Species Laurence J. Taylor, Michael Bühl, Piotr Wawrzyniak, Brian A. Chalmers, J. Derek Woollins, Alexandra M. Z. Slawin, Amy L. Fuller and Petr Kilian* School of Chemistry, EastCHEM, University of St Andrews, St Andrews, Fife, KY16 9ST, UK E-mail: [email protected] URL: http://chemistry.st-andrews.ac.uk/staff/pk/group/ Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document. Abstract Treatment of Acenap(PiPr2)(EH2) (Acenap = acenaphthene-5,6-diyl; 1a, E = As; 1b, E = P) with Ph3C·BF4 resulted in hydride abstraction to give [Acenap(PiPr2)(EH)][BF4] (2a, E = As; 2b, E = P). These represent the first structurally characterised phosphino/arsino-phosphonium salts with secondary arsine/phosphine groups, as well as the first example of a Lewis base stabilised primary arsenium cation. Compounds 2a and 2b were deprotonated with NaH to afford low co-ordinate species Acenap(PiPr2)(E) (3a, E = As; 3b, E = P). This provides an alternative and practical synthetic pathway to the phosphanylidene-σ4-phosphorane 3b and provides mechanistic insight into the formation of arsanylidene-σ4-phosphorane 3a, indirectly supporting the hypothesis that the previously reported dehydrogenation of 1a occurs via an ionic mechanism. Introduction 4 Alkylidene-σ -phosphoranes (R2C=PR3), more commonly known as Wittig reagents, are widely used intermediates in the formation of C=C double bonds. The arsenic and phosphorus equivalents, 4 4 arsanylidene-σ -phosphoranes (RAs=PR3) and phosphanylidene-σ -phosphoranes (RP=PR3), are rare 4 by comparison. -

Answer Key Chapter 16: Standard Review Worksheet – + 1

Answer Key Chapter 16: Standard Review Worksheet – + 1. H3PO4(aq) + H2O(l) H2PO4 (aq) + H3O (aq) + + NH4 (aq) + H2O(l) NH3(aq) + H3O (aq) 2. When we say that acetic acid is a weak acid, we can take either of two points of view. Usually we say that acetic acid is a weak acid because it doesn’t ionize very much when dissolved in water. We say that not very many acetic acid molecules dissociate. However, we can describe this situation from another point of view. We could say that the reason acetic acid doesn’t dissociate much when we dissolve it in water is because the acetate ion (the conjugate base of acetic acid) is extremely effective at holding onto protons and specifically is better at holding onto protons than water is in attracting them. + – HC2H3O2 + H2O H3O + C2H3O2 Now what would happen if we had a source of free acetate ions (for example, sodium acetate) and placed them into water? Since acetate ion is better at attracting protons than is water, the acetate ions would pull protons out of water molecules, leaving hydroxide ions. That is, – – C2H3O2 + H2O HC2H3O2 + OH Since an increase in hydroxide ion concentration would take place in the solution, the solution would be basic. Because acetic acid is a weak acid, the acetate ion is a base in aqueous solution. – – 3. Since HCl, HNO3, and HClO4 are all strong acids, we know that their anions (Cl , NO3 , – and ClO4 ) must be very weak bases and that solutions of the sodium salts of these anions would not be basic. -

Acids Lewis Acids and Bases Lewis Acids Lewis Acids: H+ Cu2+ Al3+ Lewis Bases

E5 Lewis Acids and Bases (Session 1) Acids November 5 - 11 Session one Bronsted: Acids are proton donors. • Pre-lab (p.151) due • Problem • 1st hour discussion of E4 • Compounds containing cations other than • Lab (Parts 1and 2A) H+ are acids! Session two DEMO • Lab: Parts 2B, 3 and 4 Problem: Some acids do not contain protons Lewis Acids and Bases Example: Al3+ (aq) = ≈ pH 3! Defines acid/base without using the word proton: + H H H • Cl-H + • O Cl- • • •• O H H Acid Base Base Acid . A BASE DONATES unbonded ELECTRON PAIR/S. An ACID ACCEPTS ELECTRON PAIR/S . Deodorants and acid loving plant foods contain aluminum salts Lewis Acids Lewis Bases . Electron rich species; electron pair donors. Electron deficient species ; potential electron pair acceptors. Lewis acids: H+ Cu2+ Al3+ “I’m deficient!” Ammonia hydroxide ion water__ (ammine) (hydroxo) (aquo) Acid 1 Lewis Acid-Base Reactions Lewis Acid-Base Reactions Example Metal ion + BONDED H H H + • to water H + • O O • • •• molecules H H Metal ion Acid + Base Complex ion surrounded by water . The acid reacts with the base by bonding to one molecules or more available electron pairs on the base. The acid-base bond is coordinate covalent. The product is a complex or complex ion Lewis Acid-Base Reaction Products Lewis Acid-Base Reaction Products Net Reaction Examples Net Reaction Examples 2+ 2+ + + Pb + 4 H2O [Pb(H2O)4] H + H2O [H(H2O)] Lewis acid Lewis base Tetra aquo lead ion Lewis acid Lewis base Hydronium ion 2+ 2+ 2+ 2+ Ni + 6 H2O [Ni(H2O)6] Cu + 4 H2O [Cu(H2O)4] Lewis acid Lewis base Hexa aquo nickel ion Lewis acid Lewis base Tetra aquo copper(II)ion DEMO DEMO Metal Aquo Complex Ions Part 1. -

Acid-Base Theories and Frontier Orbitals

Arrhenius Theory Svante Arrhenius (Swedish) 1880s Acid - a substance that produces H+(aq)in solution Base - a substance that produces OH–(aq) in solution Brønsted-Lowry Theory Johannes Brønsted (Danish) Thomas Lowry (English) 1923 Acid - a substance that donates protons (H+) Base - a substance that accepts protons (H+) Proton Transfer Reaction + + H3O (aq) + NH3(aq) 6 H2O(l) + NH4 (aq) hydronium ion ammonia water ammonium ion + H + H H H H H H O + N O + H N H H H H proton donor proton acceptor = acid = base L In general terms, all acid-base reactions fit the general pattern HA + B º A– + HB+ acid base Conjugate Acid-Base Pairs L When an acid, HA, loses a proton it becomes its conjugate base, A–, a species capable of accepting a proton in the reverse reaction. HA º A– +H+ acid conjugate base L When a base, B, gains a proton, it becomes its conjugate acid, BH+, a species capable of donating a proton in the reverse reaction. B+H+ º HB+ base conjugate acid Acid-Base Reactions L We can analyze Brønsted-Lowry type proton transfer reactions in terms of conjugate acid-base pairs. The generic reaction between HA and B can be viewed as HA º A– +H+ H+ +B º HB+ —————————————————— HA + B º A– +HB+ acid1 base2 base1 acid2 • Species with the same subscripts are conjugate acid-base pairs. Acid Hydrolysis and the Role of Solvent Water L When any Brønsted-Lowry acid HA is placed in water it undergoes + hydrolysis to produce hydronium ion, H3O , and the conjugate base, A–, according to the equilibrium: – + HA + H2O º A +H3O acid1 base2 base1 acid2 • The acid HA transfers a proton to H2O, acting as a base, thereby – + forming the conjugates A and H3O , respectively. -

Superacid Chemistry

SUPERACID CHEMISTRY SECOND EDITION George A. Olah G. K. Surya Prakash Arpad Molnar Jean Sommer SUPERACID CHEMISTRY SUPERACID CHEMISTRY SECOND EDITION George A. Olah G. K. Surya Prakash Arpad Molnar Jean Sommer Copyright # 2009 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permission. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. -

Introduction to Ionic Mechanisms Part I: Fundamentals of Bronsted-Lowry Acid-Base Chemistry

INTRODUCTION TO IONIC MECHANISMS PART I: FUNDAMENTALS OF BRONSTED-LOWRY ACID-BASE CHEMISTRY HYDROGEN ATOMS AND PROTONS IN ORGANIC MOLECULES - A hydrogen atom that has lost its only electron is sometimes referred to as a proton. That is because once the electron is lost, all that remains is the nucleus, which in the case of hydrogen consists of only one proton. The large majority of organic reactions, or transformations, involve breaking old bonds and forming new ones. If a covalent bond is broken heterolytically, the products are ions. In the following example, the bond between carbon and oxygen in the t-butyl alcohol molecule breaks to yield a carbocation and hydroxide ion. H3C CH3 H3C OH H3C + OH CH3 H3C A tertiary Hydroxide carbocation ion The full-headed curved arrow is being used to indicate the movement of an electron pair. In this case, the two electrons that make up the carbon-oxygen bond move towards the oxygen. The bond breaks, leaving the carbon with a positive charge, and the oxygen with a negative charge. In the absence of other factors, it is the difference in electronegativity between the two atoms that drives the direction of electron movement. When pushing arrows, remember that electrons move towards electronegative atoms, or towards areas of electron deficiency (positive, or partial positive charges). The electron pair moves towards the oxygen because it is the more electronegative of the two atoms. If we examine the outcome of heterolytic bond cleavage between oxygen and hydrogen, we see that, once again, oxygen takes the two electrons because it is the more electronegative atom. -

Lesson 21: Acids & Bases

Lesson 21: Acids & Bases - Far From Basic Lesson Objectives: • Students will identify acids and bases by the Lewis, Bronsted-Lowry, and Arrhenius models. • Students will calculate the pH of given solutions. Getting Curious You’ve probably heard of pH before. Many personal hygiene products make claims about pH that are sometimes based on true science, but frequently are not. pH is the measurement of [H+] ion concentration in any solution. Generally, it can tell us about the acidity or alkaline (basicness) of a solution. Click on the CK-12 PLIX Interactive below for an introduction to acids, bases, and pH, and then answer the questions below. Directions: Log into CK-12 as follows: Username - your Whitmore School Username Password - whitmore2018 Questions: Copy and paste questions 1-3 in the Submit Box at the bottom of this page, and answer the questions before going any further in the lesson: 1. After dragging the small white circles (in this simulation, the indicator papers) onto each substance, what do you observe about the pH of each substance? 2. If you were to taste each substance (highly inadvisable in the chemistry laboratory!), how would you imagine they would taste? 3. Of the three substances, which would you characterize as acid? Which as basic? Which as neutral? Use the observed pH levels to support your hypotheses. Chemistry Time Properties of Acids and Bases Acids and bases are versatile and useful materials in many chemical reactions. Some properties that are common to aqueous solutions of acids and bases are listed in the table below. Acids Bases conduct electricity in solution conduct electricity in solution turn blue litmus paper red turn red litmus paper blue have a sour taste have a slippery feeling react with acids to create a neutral react with bases to create a neutral solution solution react with active metals to produce hydrogen gas Note: Litmus paper is a type of treated paper that changes color based on the acidity of the solution it comes in contact with.