Brønsted-Lowry Acids and Bases Conjugate Acid – Base Pairs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Choosing Buffers Based on Pka in Many Experiments, We Need a Buffer That Maintains the Solution at a Specific Ph. We May Need An

Choosing buffers based on pKa In many experiments, we need a buffer that maintains the solution at a specific pH. We may need an acidic or a basic buffer, depending on the experiment. The Henderson-Hasselbalch equation can help us choose a buffer that has the pH we want. pH = pKa + log([conj. base]/[conj. acid]) With equal amounts of conjugate acid and base (preferred so buffers can resist base and acid equally), then … pH = pKa + log(1) = pKa + 0 = pKa So choose conjugates with a pKa closest to our target pH. Chemistry 103 Spring 2011 Example: You need a buffer with pH of 7.80. Which conjugate acid-base pair should you use, and what is the molar ratio of its components? 2 Chemistry 103 Spring 2011 Practice: Choose the best conjugate acid-base pair for preparing a buffer with pH 5.00. What is the molar ratio of the buffer components? 3 Chemistry 103 Spring 2011 buffer capacity: the amount of strong acid or strong base that can be added to a buffer without changing its pH by more than 1 unit; essentially the number of moles of strong acid or strong base that uses up all of the buffer’s conjugate base or conjugate acid. Example: What is the capacity of the buffer solution prepared with 0.15 mol lactic acid -4 CH3CHOHCOOH (HA, Ka = 1.0 x 10 ) and 0.20 mol sodium lactate NaCH3CHOHCOO (NaA) and enough water to make 1.00 L of solution? (from previous lecture notes) 4 Chemistry 103 Spring 2011 Review of equivalence point equivalence point: moles of H+ = moles of OH- (moles of acid = moles of base, only when the acid has only one acidic proton and the base has only one hydroxide ion). -

Protonation of Citraconic and Glutaconic Acid In

M. Jankulovska-Petkovska, M. S. Jankulovska, V. Dimova, “Protonation of citraconic and glutaconic acid…”, Technologica Acta , vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 1–8, 2019. 1 PROTONATION OF CITRAC ONIC AND GLUTACONIC ACID IN PERCHLORIC ACID MEDIA ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPER Milena Jankulovska-Petkovska 1, Mirjana S. 2 3 Jankulovska *, Vesna Dimova DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3267263 RECEIVED ACCEPTED 1 Ss Kliment Ohridski University, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine in Bitola, Macedonia 2019-01-22 2019-04-05 2 Ss. Cyril and Methodius University, Faculty of Agricultural Sciences and Food in Skopje, Macedonia 3 Ss Cyril and Methodius University, Faculty of Technology and Metallurgy in Skopje, Macedonia * [email protected] ABSTRACT: The protonation process of citraconic and glutaconic acid in perchloric acid media was followed us- ing the method of UV spectroscopy. The observed changes in the UV spectra of investigated acids confirmed that the protonation process in perchloric acid with concentration from 5 to 10 mol/dm 3 occurred. Glutaconic acid be- haved as weak organic base in perchloric acid media and existed in its monoprotonated form. On the other hand, citraconic acid existed in its protonated form and as protonated anhydride at higher perchloric acid concentra- tion. Using the absorbance data the thermodynamic dissociation constants were calculated applying the methods of Yates and McClelland, Bunnett and Olsen, and the “excess acidity” function method. The solvatation parame- ters m, m* and φφφ were evaluated, as well. In order to correct the medium effect the method of characteristic vector analysis was applied. The possible site where the protonation may take place was discussed using the partial atomic charge values determined according to AM1 and PM3 semiempirical methods. -

Laboratory Analysis of Organic Acids, 2018 Update: a Technical Standard of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG)

© American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics ACMG TECHNICAL STANDARD Laboratory analysis of organic acids, 2018 update: a technical standard of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) Renata C. Gallagher MD, PhD1, Laura Pollard, PhD2, Anna I. Scott, PhD3,4, Suzette Huguenin, PhD5, Stephen Goodman, MD6, Qin Sun, PhD7; on behalf of the ACMG Biochemical Genetics Subcommittee of the Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee Disclaimer: This laboratory standard is designed primarily as an educational resource for clinical laboratory geneticists to help them provide quality clinical laboratory genetic services. Adherence to this standard is voluntary and does not necessarily assure a successful medical outcome. This standard should not be considered inclusive of all proper procedures and tests or exclusive of other procedures and tests that are reasonably directed to obtaining the same results. In determining the propriety of any specific procedure or test, the clinical laboratory geneticist should apply his or her own professional judgment to the specific circumstances presented by the individual patient or specimen. Clinical laboratory geneticists are encouraged to document in the patient’s record the rationale for the use of a particular procedure or test, whether or not it is in conformance with this standard. They also are advised to take notice of the date any articular standard was adopted, and to consider other relevant medical and scientific information that becomes available after that date. It also would be prudent to consider whether intellectual property interests may restrict the performance of certain tests and other procedures. Organic acid analysis detects accumulation of organic acids in urine guidance for laboratory practices in organic acid analysis, and other body fluids and is a crucial first-tier laboratory test for a interpretation, and reporting. -

Organic Acids and Bases

H O H C C C C O = C C H = H C O H C O H3C aspirin CHEMISTRY 2000 Topic #3: Organic Chemistry Fall 2020 Dr. Susan Findlay See Exercises in Topic 12 Measuring Strength of Acids When you hear the term “organic acid”, it usually refers to a carboxylic acid. Carboxylic acids are readily deprotonated by strong bases: .O. .O. -... H .. H C .. H + .O H C .. + O H C O .. H C O.- .. 3 .. 3 ... acid base conjugate base conjugate acid This reaction is favoured in the forward direction because the products are lower in energy than the reactants. In particular, the conjugate base (acetate; ) is much more stable than the original base (hydroxide, ). − 32 Therefore, acetate is a weaker base than hydroxide.− Therefore, acetic acid is a stronger acid than water. 2 Measuring Strength of Acids An acid’s strength depends on the stability of its conjugate base: The conjugate base of (a strong acid; = 7) is (a very weak base) − − The conjugate base of (a weak acid; = 14) is (a relatively strong base) − 2 The strength of an acid can therefore be said to be inversely related to the strength of its conjugate base (and vice versa). Why is more stable than ? − − 32 3 Measuring Strength of Acids- Consider the reaction below. Identify the acid, base, conjugate acid and conjugate base. Is this reaction product-favoured or reactant-favoured? The of is 5. The of is 14. 32 The of 2 is 0. + 3 .O. .O. H .. H H ..+ H C .. H + O C . -

The Strongest Acid Christopher A

Chemistry in New Zealand October 2011 The Strongest Acid Christopher A. Reed Department of Chemistry, University of California, Riverside, California 92521, USA Article (e-mail: [email protected]) About the Author Chris Reed was born a kiwi to English parents in Auckland in 1947. He attended Dilworth School from 1956 to 1964 where his interest in chemistry was un- doubtedly stimulated by being entrusted with a key to the high school chemical stockroom. Nighttime experiments with white phosphorus led to the Headmaster administering six of the best. He obtained his BSc (1967), MSc (1st Class Hons., 1968) and PhD (1971) from The University of Auckland, doing thesis research on iridium organotransition metal chemistry with Professor Warren R. Roper FRS. This was followed by two years of postdoctoral study at Stanford Univer- sity with Professor James P. Collman working on picket fence porphyrin models for haemoglobin. In 1973 he joined the faculty of the University of Southern California, becoming Professor in 1979. After 25 years at USC, he moved to his present position of Distinguished Professor of Chemistry at UC-Riverside to build the Centre for s and p Block Chemistry. His present research interests focus on weakly coordinating anions, weakly coordinated ligands, acids, si- lylium ion chemistry, cationic catalysis and reactive cations across the periodic table. His earlier work included extensive studies in metalloporphyrin chemistry, models for dioxygen-binding copper proteins, spin-spin coupling phenomena including paramagnetic metal to ligand radical coupling, a Magnetochemi- cal alternative to the Spectrochemical Series, fullerene redox chemistry, fullerene-porphyrin supramolecular chemistry and metal-organic framework solids (MOFs). -

A Guide to Acids, Acid Strength, and Concentration

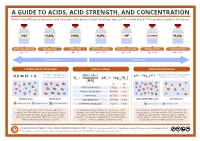

A GUIDE TO ACIDS, ACID STRENGTH, AND CONCENTRATION What’s the difference between acid strength and concentration? And how does pH fit in with these? This graphic explains the basics. CH COOH HCl H2SO4 HNO3 H3PO4 HF 3 H2CO3 HYDROCHLORIC ACID SULFURIC ACID NITRIC ACID PHOSPHORIC ACID HYDROFLUORIC ACID ETHANOIC ACID CARBONIC ACID pKa = –7 pKa = –2 pKa = –2 pKa = 2.12 pKa = 3.45 pKa = 4.76 pKa = 6.37 STRONGER ACIDS WEAKER ACIDS STRONG ACIDS VS. WEAK ACIDS ACIDS, Ka AND pKa CONCENTRATION AND pH + – The H+ ion is transferred to a + A decrease of one on the pH scale represents + [H+] [A–] pH = –log10[H ] a tenfold increase in H+ concentration. HA H + A water molecule, forming H3O Ka = pKa = –log10[Ka] – [HA] – – + + A + + A– + A + A H + H H H H A H + H H H A Ka pK H – + – H a A H A A – + A– A + H A– H A– VERY STRONG ACID >0.1 <1 A– + H A + + + – H H A H A H H H + A – + – H A– A H A A– –3 FAIRLY STRONG ACID 10 –0.1 1–3 – – + A A + H – – + – H + H A A H A A A H H + A A– + H A– H H WEAK ACID 10–5–10–3 3–5 STRONG ACID WEAK ACID VERY WEAK ACID 10–15–10–5 5–15 CONCENTRATED ACID DILUTE ACID + – H Hydrogen ions A Negative ions H A Acid molecules EXTREMELY WEAK ACID <10–15 >15 H+ Hydrogen ions A– Negative ions Acids react with water when they are added to it, The acid dissociation constant, Ka, is a measure of the Concentration is distinct from strength. -

Acid-Base Interactions in Wetting

J. rldlresiortSci. Tetltttol. \irl. -5.No. l. pp.57-69 ( l99l ) o VsP t9el. Acid-baseinteractions in wetting GEORGE M. WHITESIDES,*HANS A. BIEBUYCK.JOHN P.FOLKERS andKEVIN L. PRIME Departntent of Chentistry,Harvard Universiry',Cambridge, hlA 02138,USA Revisedversion received 27 Aueust1990 Abstract-The studv of the ionizationof carboxylicacid groups at the interfacebetween organic solidsand water demonstratesbroad similaritiesto the ionizationsof thesegroups in homogeneous aqueoussolution, but with importantsystematic differences. Creation of a chargedgroup from a neutralone by protonationor deprotonation(whether -NHr* from -NH, or -CO; from -CO,H) at the interfacebetu'een surface-functionalized polyethylene and \r'ateris more difficult than that in homogeneousaqueous solution. This differenceis probably related to the low effectivedielectric constantof the interface(5=9) relativeto water (e=80). It is not known to what extentthis differencein e (and in other propertiesof the interphase,considered as a thin solventphase) is reflectedin the stabilityof the organicions relativeto their neutral forms in the interphaseand in - solution,and to whatextent in differencesin the concentrationof H' and OH in the interphaseand in solution.Self-assembled monolayers (SAMs)-especially of terminallyfunctionalized alkanethiols (HS(CH:),,X) adsorbedon gold-provide model systemswith relativelywell-ordered structures thar are useful in establishingthe fundamentalsof ionizationof protic acidsand basesat the interface betr"'eenorganic solids and water.These systems,coupled r.r'ithnew analyticalmethods such as photoacousticcalorimetry (PAC) and contact angletitration, may make it possibleto disentangle some of the complex puzzlespresented by proton-transferreactions in the environmentof the organicsolid-* ater interphase. Keyx'ords:Contact ansle titration; photoacoustic calorimetrv: poly'ethylene carboxylic acid: contact angle:polvmer surfaces; u'etting; self-assembled monolavers. -

The Effect of Organic Acids on Base Cation Leaching from the Forest ¯Oor Under Six North American Tree Species

European Journal of Soil Science, June 2001, 52, 205±214 The effect of organic acids on base cation leaching from the forest ¯oor under six North American tree species a,c b b b a F. A. DIJKSTRA ,C.GEIBE ,S.HOLMSTROÈ M ,U.S.LUNDSTROÈ M &N.VAN BREEMEN aLaboratory of Soil Science and Geology, PO Box 37, 6700 AA Wageningen, The Netherlands, bDepartment of Chemistry and Process Technology, Mid Sweden University, 85170 Sundsvall, Sweden, and cInstitute of Ecosystem Studies, Box AB, Route 44A, Millbrook, NY 12545, USA Summary Organic acidity and its degree of neutralization in the forest ¯oor can have large consequences for base cation leaching under different tree species. We investigated the effect of organic acids on base cation leaching from the forest ¯oor under six common North American tree species. Forest ¯oor samples were analysed for exchangeable cations and forest ¯oor solutions for cations, anions, simple organic acids and acidic properties. Citric and lactic acid were the most common of the acids under all species. Malonic acid was found mainly under Tsuga canadensis (hemlock) and Fagus grandifolia (beech). The organic acids were positively correlated with dissolved organic carbon and contributed signi®cantly to the organic acidity of the solution (up to 26%). Forest ¯oor solutions under Tsuga canadensis contained the most dissolved C and the most weak acidity among the six tree species. Under Tsuga canadensis we also found signi®cant amounts of strong acidity caused by deposition of sulphuric acid from the atmosphere and by strong organic acids. Base cation exchange was the most important mechanism by which acidity was neutralized. -

Hydride Abstraction and Deprotonation – an Efficient Route to Low Co-Ordinate Phosphorus and Arsenic Species

Hydride Abstraction and Deprotonation – an Efficient Route to Low Co-ordinate Phosphorus and Arsenic Species Laurence J. Taylor, Michael Bühl, Piotr Wawrzyniak, Brian A. Chalmers, J. Derek Woollins, Alexandra M. Z. Slawin, Amy L. Fuller and Petr Kilian* School of Chemistry, EastCHEM, University of St Andrews, St Andrews, Fife, KY16 9ST, UK E-mail: [email protected] URL: http://chemistry.st-andrews.ac.uk/staff/pk/group/ Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document. Abstract Treatment of Acenap(PiPr2)(EH2) (Acenap = acenaphthene-5,6-diyl; 1a, E = As; 1b, E = P) with Ph3C·BF4 resulted in hydride abstraction to give [Acenap(PiPr2)(EH)][BF4] (2a, E = As; 2b, E = P). These represent the first structurally characterised phosphino/arsino-phosphonium salts with secondary arsine/phosphine groups, as well as the first example of a Lewis base stabilised primary arsenium cation. Compounds 2a and 2b were deprotonated with NaH to afford low co-ordinate species Acenap(PiPr2)(E) (3a, E = As; 3b, E = P). This provides an alternative and practical synthetic pathway to the phosphanylidene-σ4-phosphorane 3b and provides mechanistic insight into the formation of arsanylidene-σ4-phosphorane 3a, indirectly supporting the hypothesis that the previously reported dehydrogenation of 1a occurs via an ionic mechanism. Introduction 4 Alkylidene-σ -phosphoranes (R2C=PR3), more commonly known as Wittig reagents, are widely used intermediates in the formation of C=C double bonds. The arsenic and phosphorus equivalents, 4 4 arsanylidene-σ -phosphoranes (RAs=PR3) and phosphanylidene-σ -phosphoranes (RP=PR3), are rare 4 by comparison. -

Superacid Chemistry

SUPERACID CHEMISTRY SECOND EDITION George A. Olah G. K. Surya Prakash Arpad Molnar Jean Sommer SUPERACID CHEMISTRY SUPERACID CHEMISTRY SECOND EDITION George A. Olah G. K. Surya Prakash Arpad Molnar Jean Sommer Copyright # 2009 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permission. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. -

Soaps and Detergents • the Next Time You Are in a Supermarket, Go to the Aisle with Soaps and Detergents

23 Table of Contents 23 Unit 6: Interactions of Matter Chapter 23: Acids, Bases, and Salts 23.1: Acids and Bases 23.2: Strengths of Acids and Bases 23.3: Salts Acids and Bases 23.1 Acids • Although some acids can burn and are dangerous to handle, most acids in foods are safe to eat. • What acids have in common, however, is that they contain at least one hydrogen atom that can be removed when the acid is dissolved in water. Acids and Bases 23.1 Properties of Acids • An acid is a substance that produces hydrogen ions in a water solution. It is the ability to produce these ions that gives acids their characteristic properties. • When an acid dissolves in water, H+ ions + interact with water molecules to form H3O ions, which are called hydronium ions (hi DROH nee um I ahnz). Acids and Bases 23.1 Properties of Acids • Acids have several common properties. • All acids taste sour. • Taste never should be used to test for the presence of acids. • Acids are corrosive. Acids and Bases 23.1 Properties of Acids • Acids also react with indicators to produce predictable changes in color. • An indicator is an organic compound that changes color in acid and base. For example, the indicator litmus paper turns red in acid. Acids and Bases 23.1 Common Acids • At least four acids (sulfuric, phosphoric, nitric, and hydrochloric) play vital roles in industrial applications. • This lists the names and formulas of a few acids, their uses, and some properties. Acids and Bases 23.1 Bases • You don’t consume many bases. -

Introduction to Ionic Mechanisms Part I: Fundamentals of Bronsted-Lowry Acid-Base Chemistry

INTRODUCTION TO IONIC MECHANISMS PART I: FUNDAMENTALS OF BRONSTED-LOWRY ACID-BASE CHEMISTRY HYDROGEN ATOMS AND PROTONS IN ORGANIC MOLECULES - A hydrogen atom that has lost its only electron is sometimes referred to as a proton. That is because once the electron is lost, all that remains is the nucleus, which in the case of hydrogen consists of only one proton. The large majority of organic reactions, or transformations, involve breaking old bonds and forming new ones. If a covalent bond is broken heterolytically, the products are ions. In the following example, the bond between carbon and oxygen in the t-butyl alcohol molecule breaks to yield a carbocation and hydroxide ion. H3C CH3 H3C OH H3C + OH CH3 H3C A tertiary Hydroxide carbocation ion The full-headed curved arrow is being used to indicate the movement of an electron pair. In this case, the two electrons that make up the carbon-oxygen bond move towards the oxygen. The bond breaks, leaving the carbon with a positive charge, and the oxygen with a negative charge. In the absence of other factors, it is the difference in electronegativity between the two atoms that drives the direction of electron movement. When pushing arrows, remember that electrons move towards electronegative atoms, or towards areas of electron deficiency (positive, or partial positive charges). The electron pair moves towards the oxygen because it is the more electronegative of the two atoms. If we examine the outcome of heterolytic bond cleavage between oxygen and hydrogen, we see that, once again, oxygen takes the two electrons because it is the more electronegative atom.