SESSION I : Geographical Names and Sea Names

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Oder-Neisse Line As Poland's Western Border

Piotr Eberhardt Piotr Eberhardt 2015 88 1 77 http://dx.doi.org/10.7163/ GPol.0007 April 2014 September 2014 Geographia Polonica 2015, Volume 88, Issue 1, pp. 77-105 http://dx.doi.org/10.7163/GPol.0007 INSTITUTE OF GEOGRAPHY AND SPATIAL ORGANIZATION POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES www.igipz.pan.pl www.geographiapolonica.pl THE ODER-NEISSE LINE AS POLAND’S WESTERN BORDER: AS POSTULATED AND MADE A REALITY Piotr Eberhardt Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization Polish Academy of Sciences Twarda 51/55, 00-818 Warsaw: Poland e-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article presents the historical and political conditioning leading to the establishment of the contemporary Polish-German border along the ‘Oder-Neisse Line’ (formed by the rivers known in Poland as the Odra and Nysa Łużycka). It is recalled how – at the moment a Polish state first came into being in the 10th century – its western border also followed a course more or less coinciding with these same two rivers. In subsequent cen- turies, the political limits of the Polish and German spheres of influence shifted markedly to the east. However, as a result of the drastic reverse suffered by Nazi Germany, the western border of Poland was re-set at the Oder-Neisse Line. Consideration is given to both the causes and consequences of this far-reaching geopolitical decision taken at the Potsdam Conference by the victorious Three Powers of the USSR, UK and USA. Key words Oder-Neisse Line • western border of Poland • Potsdam Conference • international boundaries Introduction districts – one for each successor – brought the loss, at first periodically and then irrevo- At the end of the 10th century, the Western cably, of the whole of Silesia and of Western border of Poland coincided approximately Pomerania. -

Pomerania in the Medieval and Renaissance Cartography – from the Cottoniana to Eilhard Lubinus

Pomerania in the Medieval and Renaissance Cartography… STUDIA MARITIMA, vol. XXXIII (2020) | ISSN 0137-3587 | DOI: 10.18276/sm.2020.33-04 Adam Krawiec Faculty of Historical Studies Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0002-3936-5037 Pomerania in the Medieval and Renaissance Cartography – from the Cottoniana to Eilhard Lubinus Keywords: Pomerania, Duchy of Pomerania, medieval cartography, early modern cartography, maritime cartography The following paper deals with the question of the cartographical image of Pomer- ania. What I mean here are maps in the modern sense of the word, i.e. Graphic rep- resentations that facilitate a spatial understanding of things, concepts, conditions, processes, or events in the human world1. It is an important reservation because the line between graphic and non-graphic representations of the Earth’s surface in the Middle Ages was sometimes blurred, therefore the term mappamundi could mean either a cartographic image or a textual geographical description, and in some cases it functioned as an equivalent of the modern term “Geography”2. Consequently, there’s a tendency in the modern historiography to analyze both forms of the geographical descriptions together. However, the late medieval and early modern developments in the perception and re-constructing of the space led to distinguishing cartography as an autonomous, full-fledged discipline of knowledge, and to the general acceptance of the map in the modern sense as a basic form of presentation of the world’s surface. Most maps which will be examined in the paper were produced in this later period, so it seems justified to analyze only the “real” maps, although in a broader context of the geographical imaginations. -

Risk Assessment of Virus Infections in the Oder Estuary (Southern Baltic) on the Basis of Spatial Transport and Virus Decay Simulations

International Journal Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 203, 317-325 (2001) © Urban & Fischer Verlag of Hygiene and http://www.urbanfischer.de/journals/intjhyg Environmental Health Risk assessment of virus infections in the Oder estuary (southern Baltic) on the basis of spatial transport and virus decay simulations Gerald Schernewski1, Wolf-Dieter Jülich2 1 Baltic Sea Research Institute Warnemünde, Rostock-Warnemünde, Germany 2 Institute of Pharmacy, University of Greifswald, Germany Received September 13, 2000 · Accepted January 09, 2001 Abstract The large Oder (Szczecin) Lagoon (687 km2) at the German-Polish border, close to the Baltic Sea, suffers from severe eutrophication and water quality problems due to high discharge of water, nu- trients and pollutants by the river Oder. Sewage treatment around the lagoon has been very much improved during the last years, but large amounts of sewage still enter the Oder river. Human path- ogenic viruses generally can be expected in all surface waters that are affected by municipal sewage. There is an increasing awareness that predisposed persons can be infected by a few infective units or even a single active virus. Another new aspect is, that at least polioviruses attached to suspend- ed particles can be infective for weeks and therefore be transported over long distances. Therefore, the highest risk of virus inputs arise from the large amounts of untreated sewage of the city of Szcze- cin (Poland), which are released into the river Oder and transported to the lagoon and the Baltic Sea. Summer tourism is the most important economical factor in this coastal region and further growth is expected. -

Language Contact in Pomerania: the Case of German, Polish, and Kashubian

P a g e | 1 Language Contact in Pomerania: The Case of German, Polish, and Kashubian Nick Znajkowski, New York University Purpose The effects of language contact and language shift are well documented. Lexical items and phonological features are very easily transferred from one language to another and once transferred, rather easily documented. Syntactic features can be less so in both respects, but shifts obviously do occur. The various qualities of these shifts, such as whether they are calques, extensions of a structure present in the modifying language, or the collapsing of some structure in favor the apparent simplicity found in analogous foreign structures, all are indicative of the intensity and the duration of the contact. Additionally, and perhaps this is the most interesting aspect of language shift, they show what is possible in the evolution of language over time, but also what individual speakers in a single generation are capable of concocting. This paper seeks to explore an extremely fascinating and long-standing language contact situation that persists to this day in Northern Poland—that of the Kashubian language with its dominating neighbors: Polish and German. The Kashubians are a Slavic minority group who have historically occupied the area in Northern Poland known today as Pomerania, bordering the Baltic Sea. Their language, Kashubian, is a member of the Slavic branch of Indo-European languages and further belongs to the Pomeranian branch of Lechitic languages, which includes Polish, Silesian, and the extinct Polabian and Slovincian. The situation to be found among the Kashubian people, a people at one point variably bi-, or as is sometimes the case among older folk, even trilingual in Kashubian, P a g e | 2 Polish, and German is a particularly exciting one because of the current vitality of the Kashubian minority culture. -

Pomorskie Voivodeship Development Strategy 2020

Annex no. 1 to Resolution no. 458/XXII/12 Of the Sejmik of Pomorskie Voivodeship of 24th September 2012 on adoption of Pomorskie Voivodeship Development Strategy 2020 Pomorskie Voivodeship Development Strategy 2020 GDAŃSK 2012 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. OUTPUT SITUATION ………………………………………………………… 6 II. SCENARIOS AND VISION OF DEVELOPMENT ………………………… 18 THE PRINCIPLES OF STRATEGY AND ROLE OF THE SELF- III. 24 GOVERNMENT OF THE VOIVODESHIP ………..………………………… IV. CHALLENGES AND OBJECTIVES …………………………………………… 28 V. IMPLEMENTATION SYSTEM ………………………………………………… 65 3 4 The shape of the Pomorskie Voivodeship Development Strategy 2020 is determined by 8 assumptions: 1. The strategy is a tool for creating development targeting available financial and regulatory instruments. 2. The strategy covers only those issues on which the Self-Government of Pomorskie Voivodeship and its partners in the region have a real impact. 3. The strategy does not include purely local issues unless there is a close relationship between the local needs and potentials of the region and regional interest, or when the local deficits significantly restrict the development opportunities. 4. The strategy does not focus on issues of a routine character, belonging to the realm of the current operation and performing the duties and responsibilities of legal entities operating in the region. 5. The strategy is selective and focused on defining the objectives and courses of action reflecting the strategic choices made. 6. The strategy sets targets amenable to verification and establishment of commitments to specific actions and effects. 7. The strategy outlines the criteria for identifying projects forming part of its implementation. 8. The strategy takes into account the specific conditions for development of different parts of the voivodeship, indicating that not all development challenges are the same everywhere in their nature and seriousness. -

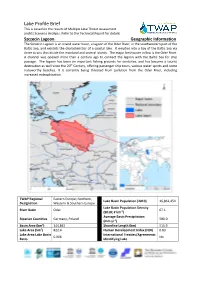

Lake Profile Brief This Is Based on the Results of Multiple Lake Threat Assessment and Its Scenario Analysis

Lake Profile Brief This is based on the results of Multiple Lake Threat Assessment and its Scenario Analysis. Refer to the Technical Report for details. Szczecin Lagoon Geographic Information The Szczecin Lagoon is an inland water basin, a lagoon of the Oder River, in the southwestern part of the Baltic Sea, and exhibits the characteristics of a coastal lake. It empties into a bay of the Baltic Sea via three straits that divide the mainland and several islands. The major freshwater inflow is the Oder River. A channel was opened more than a century ago to connect the lagoon with the Baltic Sea for ship passage. The lagoon has been an important fishing grounds for centuries, and has become a tourist destination as well since the 20th Century, offering passenger ship tours, various water sports and some noteworthy beaches. It is currently being threated from pollution from the Oder River, including increased eutrophication. TWAP Regional Eastern Europe; Northern, Lake Basin Population (2010) 16,862,454 Designation Western & Southern Europe Lake Basin Population Density River Basin Oder 67.1 (2010; # km‐2) Average Basin Precipitation Riparian Countries Germany, Poland 580.0 (mm yr‐1) Basin Area (km2) 144,845 Shoreline Length (km) 515.9 Lake Area (km2) 822.4 Human Development Index (HDI) 0.83 Lake Area:Lake Basin International Treaties/Agreements 0.006 No Ratio Identifying Lake Szczecin Lagoon Basin Characteristics (a) Szczecin Lagoon basin and associated transboundary water systems (b) Szczecin Lagoon basin land use Szczecin Lagoon Threat Ranking A serious lack of global‐scale uniform data on the TWAP transboundary in‐lake conditions required their potential threat risks be estimated on the basis of the characteristics of their drainage basins, rather than in‐lake conditions. -

The River Odra Estuary As a Gateway for Alien Species Immigration to the Baltic Sea Basin Das Oderästuar Als Pfad Für Die Einwanderung Von Alienspezies in Die Ostsee

Acta hydrochim. hydrobiol. 27 (1999) 5, 374-382 © WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH, D-69451 Weinheim, 1999 0323 - 4320/99/0509-0374 $ 17.50+.50/0 The River Odra Estuary as a Gateway for Alien Species Immigration to the Baltic Sea Basin Das Oderästuar als Pfad für die Einwanderung von Alienspezies in die Ostsee Dr. Piotr Gruszka Department of Marine Ecology and Environmental Protection, Agricultural University in Szczecin, ul. Kazimierza Królewicza 4/H, PL 71-550 Szczecin, Poland E-mail: [email protected] Summary: The river Odra estuary belongs to those water bodies in the Baltic Sea area which are most exposed to immigration of alien species. Non-indigenous species that have appeared in the Szczecin Lagoon (i.a. Dreissena polymorpha, Potamopvrgus antipodarum, Corophium curvispinum) and in the Pomeranian Bay (Cordylophora caspia, Mya arenaria, Balanus improvisus, Acartia tonsa) in historical time and which now are dominant components of animal communities there as well as other and less abundant (or less common) alien species in the estuary (e.g. Branchiura sowerbyi, Eriocheir sinensis, Orconectes limosus) are presented. In addition, other newcomers - Marenzelleria viridis, Gammarus tigrinus, and Pontogammarus robustoides - found in the estuary in the recent ten years are described. The significance of the sea and inland water transport in the region for introduction of non-indigenous species is discussed against the background of the distribution pattern of these recently introduced polychaete and gammarid species. Keywords: Alien Species, Marenzelleria viridis, Gammarus tigrinus, Pontogammarus robustoides, River Odra Estuary Zusammenfassung: Das Oderästuar gehört zu den Bereichen der Ostsee, die am meisten der Einwanderung von Alienspezies ausgesetzt sind. -

Managing Eutrophication in the Szczecin (Oder) Lagoon-Development, Present State and Future Perspectives

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 16 January 2019 doi: 10.3389/fmars.2018.00521 Managing Eutrophication in the Szczecin (Oder) Lagoon-Development, Present State and Future Perspectives René Friedland 1*, Gerald Schernewski 1,2, Ulf Gräwe 1, Inga Greipsland 3, Dalila Palazzo 1,4 and Marianna Pastuszak 5 1 Leibniz-Institute for Baltic Sea Research Warnemünde, Rostock, Germany, 2 Klaipeda University Marine Science and Technology Center, Klaipeda,˙ Lithuania, 3 Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research, Ås, Norway, 4 STA Engineering, Pinerolo, Italy, 5 National Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Gdynia, Poland High riverine nutrient loads caused poor water quality, low water transparency and an unsatisfactory ecological status in the Szczecin (Oder) Lagoon, a trans-boundary water at the southern shore of the Baltic Sea. Total annual riverine N (P) loads into the lagoon raised at the 20th century from approximately 14,000 t TN (1,000 t TP) to 115,000 t TN (10,500 t TP) in the 1980ties and declined to about 56,750 t TN (2,800 t TP) after 2010. Nutrient concentrations, water transparency (Secchi depth) and chlorophyll-a showed a Edited by: positive response to the reduced nutrient loads in the Polish eastern lagoon. This was not Marianne Holmer, the case in the German western lagoon, where summer Secchi depth is 0.6 m and mean University of Southern Denmark, Denmark chlorophyll-a concentration is four times above the threshold for the Good Ecological Reviewed by: Status. Measures to improve the water quality focused until now purely on nutrient load Angel Pérez-Ruzafa, reductions, but the nutrient load targets and Maximal Allowable Inputs are contradicting University of Murcia, Spain Nafsika Papageorgiou, between EU Water Framework Directive and EU Marine Strategy Framework Directive. -

Traces Under Water Exploring and Protecting the Cultural Heritage in the North Sea and Baltic Sea

2019 | Discussion No. 23 Traces under water Exploring and protecting the cultural heritage in the North Sea and Baltic Sea Christian Anton | Mike Belasus | Roland Bernecker Constanze Breuer | Hauke Jöns | Sabine von Schorlemer Publication details Publisher Deutsche Akademie der Naturforscher Leopoldina e. V. – German National Academy of Sciences – President: Prof. Dr. Jörg Hacker Jägerberg 1, D-06108 Halle (Saale) Editorial office Christian Anton, Constanze Breuer & Johannes Mengel, German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina Copy deadline November 2019 Contact [email protected] Image design Sarah Katharina Heuzeroth, Hamburg Cover image Sarah Katharina Heuzeroth, Hamburg Fictitious representation of the discovery of a hand wedge using a submersible: The exploration of prehistoric landscapes in the sediments of the North Sea and Baltic Sea could one day lead to the discovery of traces of human activity or campsites. Translation GlobalSprachTeam ‒ Sassenberg+Kollegen, Berlin Proofreading Alan Frostick, Frostick & Peters, Hamburg Typesetting unicommunication.de, Berlin Print druckhaus köthen GmbH & Co. KG ISBN 978-3-8047-4070-9 Bibliographic Information of the German National Library The German National Library lists this publication in the German National Bibliography. Detailed bibliographic data are available online at http://dnb.d-nb.de. Suggested citation Anton, C., Belasus, M., Bernecker, R., Breuer, C., Jöns, H., & Schorlemer, S. v. (2019). Traces under water. Exploring and protecting the cultural heritage in the North Sea and Baltic Sea. Halle (Saale): German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina. Traces under water Exploring and protecting the cultural heritage in the North Sea and Baltic Sea Christian Anton | Mike Belasus | Roland Bernecker Constanze Breuer | Hauke Jöns | Sabine von Schorlemer The Leopoldina Discussions series publishes contributions by the authors named. -

POMERANIAN COINS from the 16Th- 18Th CENTURIES STATE of INVESTIGATIONS and PERSPECTIVES

FASCICULI ARCHAKOLOGIAt HISTORICAL, Fase. III. 1988 PL ISSN 0860-0007 JERZY PINIŃSKI POMERANIAN COINS FROM THE 16th- 18th CENTURIES STATE OF INVESTIGATIONS AND PERSPECTIVES West Pomerania is a specific territory at the point Museum in Szczecin. However, even this collection is of contact of several cultures. That is why it is totally not complete. In other Polish museums modern West different, from the point of view of minting history as Pomeranian coins are represented in more than in- well, from other territories of Polish country. Initially, conspicuous way. One can only mention here a small having been settled by the Slavic tribes, Pomerania was number of West Pomeranian coins in Regional Mu- the aim of expansion from various sides. Having been seum in Słupsk, few treasures preserved in Regional not powerful enough to protect itself against that Museum in Koszalin and a very modest collection in expansion, the country resorted the policy of maintai- National Museum in Warsaw which possesses several ning the balance in relations with its neighbours and interesting specimens yet no research basis. Pomeranian dukes often had to recognize the sove- There is no significant private collection of West reignty of foreign rulers paying homage to them. Pomeranian coins in Poland. The best example illu- Pomerania was subdued by Denmark, the Empire, strating this paucity is the number of gold west Brandenburg and Poland. In this way, west Pomera- Pomeranian coins preserved in collections which nian dukes managed to maintain a relative indepen- comes up to 2 specimens and any Polish museum does dence for half a thousand years though it was not an not possess a single gold coin from the ducal period. -

In Pomerania Bay, Gdansk Bay and Curonian Lagoon

Journal of Elementology ISSN 1644-2296 Pilarczyk B., Pilecka-Rapacz M., Tomza-Marciniak A., Domagała J., Bąkowska M., Pilarczyk R. 2015. Selenium content in European smelt (Osmerus eperlanus eperlanus L.) in Pomerania Bay, Gdansk Bay and Curonian Lagoon. J. Elem., 20(4): 957-964. DOI: 10.5601/jelem.2015.20.1.876 SELENIUM CONTENT IN EUROPEAN SMELT (OSMERUS EPERLANUS EPERLANUS L.) IN POMERANIA BAY, GDANSK BAY AND CURONIAN LAGOON Bogumiła Pilarczyk1, Małgorzata Pilecka-Rapacz2, Agnieszka Tomza-Marciniak1, Józef Domagała2, Małgorzata Bąkowska1, Renata Pilarczyk3 1Chair of Animal Reproduction Biotechnology and Environmental Hygiene West Pomeranian University of Technology in Szczecin 2 Chair of General Zoology University of Szczecin 3Laboratory of Biostatistics West Pomeranian University of Technology in Szczecin Abstract Migratory smelt (Osmerus eperlanus eperlanus L.) may be perceived as a valuable indicative organism in monitoring the current environmental status and in assessment of a potential risk caused by selenium pollution. The aim of the study was to compare the selenium content in the European smelt from the Bay of Pomerania, Gdansk, and the Curonian Lagoon. The experimen- tal material consisted of smelt samples (muscle) caught in the bays of Gdansk and Pomerania and the Curonian Lagoon (estuaries of the three largest rivers in the Baltic Sea basin: the Oder, the Vistula and the Neman). A total of 133 smelt were examined (Pomerania Bay n = 67; Gdansk Bay n = 35; Curonian Lagoon n = 31). Selenium concentrations were determined spec- trofluorometrically. The data were analyzed statistically using one-way analysis of variance, calculated in Statistica PL software. The region of fish collection significantly affected the content of selenium in the examined smelts. -

Guideline for Seafloor Mapping in German Marine Waters

Guideline for Seafloor Mapping in German Marine Waters Using High-Resolution Sonars Guideline for Seafloor Mapping in German Marine Waters Using High-Resolution Sonars Version 1.0 30.04.2016 This guideline has been developed by the following people: Dr. Claudia Propp2 (Coordination) Dr. Svenja Papenmeier1 Dr. Alexander Bartholomä5 Dr. Peter Richter 3 Dr. Christian Hass1 Dr. Klaus Schwarzer 3 Dr. Peter Holler 5 Dr. Franz Tauber 4 Maria Lambers-Huesmann 2 Dr. Manfred Zeiler 2 1 Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Wadden Sea Station Sylt (AWI) 2 Federal Maritime and Hydrographic Agency (BSH) 3 Christian Albrecht University of Kiel, Institute of Geosciences (CAU) 4 Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research, Department of Marine Geology (IOW) 5 Senckenberg am Meer, Wilhelmshaven © Federal Maritime and Hydrographic Agency (BSH) Hamburg and Rostock 2016 www.bsh.de BSH No. 7201 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or processed, copied, or distributed using electronic systems without the written permission of the BSH. This document should be cited as follows: BSH, 2016: Guideline for Seafloor Mapping in German Marine Waters Using High-Resolution Sonars. BSH No. 7201, 147 p. Translated by ConTec Fachübersetzungen GmbH and reviewed by Dr. Claudia Propp Cover photos by courtesy of: Dr. Svenja Papenmeier – AWI Dr. Franz Tauber – IOW Notice 3 Notice This guideline was created under consideration of contributions from the following people: Roland Atzler 10 Dr. Jürgen Knaack 8 Dr. Jan Witt 8 Cordula Berkenbrink 9 Kerstin Kolbe 8 Frank Wolf 5 Tim Bildstein11 Francesco Mascioli 9 Dr.-Ing.