The Year of the Animal in France

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Print Format

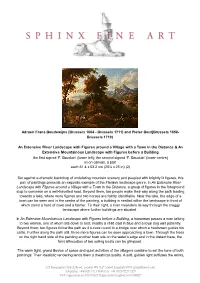

Adraen Frans Boudewijns (Brussels 1664 - Brussels 1711) and Pieter Bout[Brussels 1658- Brussels 1719) An Extensive River Landscape with Figures around a Village with a Town in the Distance & An Extensive Mountainous Landscape with Figures before a Building the first signed ‘F. Bauduin’ (lower left); the second signed ‘F. Bauduin’ (lower centre) oil on canvas, a pair each 51.4 x 63.2 cm (20¼ x 25 in) (2) Set against a dramatic backdrop of undulating mountain scenery and peopled with brightly lit figures, this pair of paintings presents an exquisite example of the Flemish landscape genre. In An Extensive River Landscape with Figures around a Village with a Town in the Distance, a group of figures in the foreground stop to converse on a well-travelled road. Beyond them, two people make their way along the path leading towards a lake, where more figures and two horses are faintly identifiable. Near the lake, the edge of a town can be seen and in the centre of the painting, a building is nestled within the landscape in front of which stand a herd of cows and a farmer. To their right, a river meanders its way through the craggy landscape where further buildings are situated. In An Extensive Mountainous Landscape with Figures before a Building, a horseman passes a man talking to two women, one of whom sits down to rest; nearby a child clad in blue and a loyal dog wait patiently. Beyond them, two figures follow the path as it curves round to a bridge over which a herdsman guides his cattle. -

Descartes' Bête Machine, the Leibnizian Correction and Religious Influence

University of South Florida Digital Commons @ University of South Florida Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 4-7-2010 Descartes' Bête Machine, the Leibnizian Correction and Religious Influence John Voelpel University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Philosophy Commons Scholar Commons Citation Voelpel, John, "Descartes' Bête Machine, the Leibnizian Correction and Religious Influence" (2010). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/etd/3527 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Digital Commons @ University of South Florida. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University of South Florida. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Descartes’ Bête Machine, the Leibnizian Correction and Religious Influence by John Voelpel A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Martin Schönfeld, Ph.D. Roger Ariew, Ph.D. Stephen Turner, Ph.D. Date of Approval: April 7, 2010 Keywords: environmental ethics, nonhuman animals, Montaigne, skepticism, active force, categories © Copyright 2010, John W. Voelpel 040410 Note to Reader: Because the quotations from referenced sources in this paper include both parentheses and brackets, this paper uses braces “{}” in any location {inside or outside of quotations} for the writer’s parenthetical-like additions in both text and footnotes. 040410 Table of Contents Abstract iii I. Introduction 1 II. Chapter One: Montaigne: An Explanation for Descartes’ Bête Machine 4 Historical Environment 5 Background Concerning Nonhuman Nature 8 Position About Nature Generally 11 Position About Nonhuman Animals 12 Influence of Religious Institutions 17 Summary of Montaigne’s Perspective 20 III. -

Boel, Etude De Lions

Fiche oeuvre Auteur Pieter Boel (Anvers, 1625 – Paris, septembre 1674) œuvre Etude de lions Date Entre 1668 et 1674 Technique Huile sur toile Dimensions 71,2 x 92 cm Provenance Décors de la ménagerie de Versailles, répartis à la fin du XIXe siècle dans les Musées de France. Mots-clés Lion, Versailles, Dessin scientifique. CONTEXTE Le règne de Louis XIV (1661-1715) marque l'apogée du premier empire colonial français. Placées sous l'autorité du secrétariat d'Etat à la marine puis sous celle d'un bureau des colonies, les possessions françaises sont au cœur d'un commerce florissant régi par le système de l'Exclusif, aucune colonie n'étant autorisée à faire commerce avec l'étranger. Selon le mercantilisme de Colbert et comme le mentionne l'Encyclopédie : Les colonies n'ont été fondées que pour l'utilité de la métropole. Cette nouvelle prospérité permet le développement considérable de ports comme Nantes, Bordeaux ou Lorient. Au cœur de cette économie coloniale, l'esclavage, régi par le Code noir de 1685, est alimenté par le commerce triangulaire. Les esclaves, tous originaires d'Afrique, sont alors considérés comme une marchandise. Ils permettent également l’importation d’animaux rares comme le lion. ARTISTE Initié par son père graveur, Pieter Boel entre en apprentissage probablement chez les peintres de natures mortes et d’animaux d’Anvers Frans Snyders puis Ian Fyt. Entre 1647 et 1649, il se perfectionne en Italie où il rencontre un vif succès notamment à Rome et Gênes, où il s’inspire des compositions animalières de Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione. De retour à Anvers vers 1650, il est reçut franc maître de la guilde et il s’y marie. -

Louis XIV: Art As Persuasion Supporting the Dominance of France in 17Th Century Europe

Lindenwood University Digital Commons@Lindenwood University Student Research Papers Research, Scholarship, and Resources Fall 11-30-2010 Louis XIV: Art as Persuasion Supporting the Dominance of France in 17th Century Europe Matthew Noblett [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lindenwood.edu/student-research-papers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Noblett, Matthew, "Louis XIV: Art as Persuasion Supporting the Dominance of France in 17th Century Europe" (2010). Student Research Papers. 1. https://digitalcommons.lindenwood.edu/student-research-papers/1 This Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Research, Scholarship, and Resources at Digital Commons@Lindenwood University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Lindenwood University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Louis XIV: Art as Persuasion Supporting the Dominance of France in 17th Century Europe Matthew D. Noblett 11/30/10 Dr. James Hutson ART 55400.31 Lindenwood University Noblett 1 In 17th century France there was national funding combined with strict controls placed on the arts and all areas of the administration of Louis XIV. This was imperative to present the country as one of the greatest European powers of its time. It was done by creating personas of Louis as the Sun King, sole administrator of France or “'L'etat c' est moi” (I am the State) and conqueror. All were reinforced and often invented in rigid confines through state funded propaganda. His name has become synonymous with the French arts of the 17th century through significant investments in all forms of media, from poetry, music and theatre to painting, sculpture and architecture. -

Statecraft and Insect Oeconomies in the Global French Enlightenment (1670-1815)

Statecraft and Insect Oeconomies in the Global French Enlightenment (1670-1815) Pierre-Etienne Stockland Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2017 Etienne Stockland All rights reserved ABSTRACT Statecraft and Insect Oeconomies in the Global French Enlightenment (1670-1815) Pierre-Etienne Stockland Naturalists, state administrators and farmers in France and its colonies developed a myriad set of techniques over the course of the long eighteenth century to manage the circulation of useful and harmful insects. The development of normative protocols for classifying, depicting and observing insects provided a set of common tools and techniques for identifying and tracking useful and harmful insects across great distances. Administrative techniques for containing the movement of harmful insects such as quarantine, grain processing and fumigation developed at the intersection of science and statecraft, through the collaborative efforts of diplomats, state administrators, naturalists and chemical practitioners. The introduction of insectivorous animals into French colonies besieged by harmful insects was envisioned as strategy for restoring providential balance within environments suffering from human-induced disequilibria. Naturalists, administrators, and agricultural improvers also collaborated in projects to maximize the production of useful substances secreted by insects, namely silk, dyes and medicines. A study of -

A Visitors Guide To

A Guide to St Elizabeth’s Roman Catholic Church Scarisbrick Mary Ormsby, Veronica & Tom Massam 1 This guide is dedicated to all parishioners and Priests, past and present, who over the generations have built and supported the Church and Catholic school in Scarisbrick. 2 Acknowledgements This guide would never have been brought to fruition without the help, support and encouragement of many people especially parishioners who loaned old photographs, alas we did not have space to include them all. The research itself has been a team effort over many years and we would like to thank the archivists and staff at Lancashire Records Office and the National Archives where most of the research was done. In addition Abbot Geoffrey Scott of Douai Abbey has provided much useful information and insight. Count Jean-Denis de Castéja, great grandson of Marie Emmanuel Count de Castéja who along with his father was responsible for the building of St Elizabeth’s, has provided many family photos and personal details. He continues to inspire and support our work. Thanks are also due to the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society who allowed us to publish the map showing the sites of the mediaeval crosses, the Liverpool Echo and the Trustees of Douai Abbey for permission to reproduce photographs of members of the parish who became priests. As a group of scientists we needed help with our grammar, punctuation and editing, many thanks to Joe McNamara, Joan Taylor and Fr Hugh Somerville Knapmann OSB who have spent many hours helping to shape this final version of the guide. -

David Garrioch, the Local Experience of Revolution: the Gobelins

20 French History and Civilization The local experience of Revolution: the Gobelins/Finistère Section in Paris David Garrioch Viewed from afar, the French Revolution falls easily into a series of binary oppositions: revolutionary and counter-revolutionary; conservative and radical; bourgeois and popular; Paris and provinces. Such opposites were the stuff of revolutionary rhetoric and provided ready ways of making sense of a complex reality. Yet, as every historian of the Revolution knows, on the ground things were much more complicated. In the provinces, revolutionary labels like “Jacobin” could cover a range of political views and were often ways of aligning one local faction with the group that was in power at the centre. This happened even in Paris itself. Historians often use these oppositions in order to explain the Revolution to students and to general readers. Yet when the oppositions used are invested with moral qualities, or when alignments are made between different descriptive categories, binary oppositions betray the historical reality they claim to represent. An example is the correspondence often made between “radical” politics, the “popular movement,” and revolutionary violence. None of these terms is clear-cut. What was “radical” in 1789 was not necessarily so in 1793. Individuals and groups who expressed “radical” views at one moment did not always do so consistently, and nor were they necessarily “radical” on every issue. The way the term “popular movement” has commonly been used is also a problem, as recent studies of the post-1795 religious revival have demonstrated. Whereas dechristianization was long associated with the “popular movement,” particularly in Paris, and the re-opening of churches with counter-revolution, there is now ample evidence that the religious revival was more “popular” than dechristianization.1 Similarly, recent writing has shown that hostility to women’s involvement in politics was by no means a monopoly of counter- revolutionaries or even of bourgeois moderates. -

The Thorax in History 3. Beginning of the Middle Ages

Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thx.33.3.295 on 1 June 1978. Downloaded from Thorax, 1978, 33, 295-306 The thorax in history 3. Beginning of the Middle Ages R. K. FRENCH From the Wellcome Unit for the History of Medicine, University of Cambridge The end of Hellenistic experiment and observation physicians and surgeons did not give the Alexandrians the importance that historical hind- When Galen died at the end of the second century, sight attributes to them, nor did they recognise anatomical and physiological research died with Galen as authoritative as Galen's and later ages him. We are effectively in the dark ages at once, believed him to be. To a certain extent this is for the continued, if precarious, political stability true of the East as of the West: Aretaeus of of the Roman Empire was no substitute for the Cappadocia in Asia Minor was contemporary with, loss of vigour of the Greek intellectual tradition. or slightly later than Galen, but does not mention Galen's works survived, were commented upon him. Fragments of anatomy and physiology that and summarised, but no new inquiry was under- can be gleaned from his surviving works on the taken. When Galen visited Rome, it was as far signs and causes of acute and chronic diseases3 west as anatomy and physiology came: Pergamon, come from a variety of sources, some of them Alexandria, and Ephesus were the inheritors of purely traditional. Indeed, in Aretaeus we see an intellectual climate that sustained anatomy in more clearly than in Galen's synthetic physiology any form other than that employed by the sur- a distinction between traditional, literary anatomy, http://thorax.bmj.com/ geons of the legions. -

Motion in Art, Chapter 1

Motion in Art, chapter 1 Introduction In the deepest part of the Altamira caves, in the North of Spain, the walls and ceilings are covered with images. The most surprising are the polychrome paintings on the ceiling. They cover a surface of 18 meters by 9 and we see deer and wild boar as well as the massive shapes of bison. These images, which were made between 18 000 and 14 000 BC, are of a surprisingly high artistic quality. We are not sure why they were made. Some historians offer religious reasons. The place of the paintings, in the deepest, darkest, and most inaccessible part of the cave, as far from reality as possible, would indicate an area of ritual acts. Maybe they were made to summon an abundance of game, or bravery during the hunt? Other historians believe that, due to the remarkable artistic quality of the images, they are unique, individual creations. To support their claim, they draw our attention to the clever use the artist made of the unevenness of the walls and ceiling to give the animals relief and, in that way, emphasize to their weighty presence. Or they mention the variation in color and hue, or the exquisite treatment of shadow and light. Art historian Siegfried Giedion adds another aspect to the paintings. Motion. The photo-images we look at can be deceptive when we try to discover what purpose these paintings served. As Giedion explains, these images should be examined by the flickering light of a torch, or that of a wick floating in animal fat. -

Anatomy, Technology, and the Inhuman in Descartes

UCLA Paroles gelées Title Virtual Bodies: Anatomy, Technology, and the Inhuman in Descartes Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5ww094n7 Journal Paroles gelées, 16(1) ISSN 1094-7264 Author Judovitz, Dalia Publication Date 1998 DOI 10.5070/PG7161003078 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Virtual Bodies: Anatomy, Technology, and the Inhuman in Descartes Dalia Judo vitz Rene Descartes's Discourse on the Method (1637) marks a major turning point in the representation of the body in the Western tradition. Rather than valorizing the lived body and no- tions of experience, as his predecessor Michel de Montaigne had done in The Essays (1588), Descartes focuses on the body no longer as subject, but as object of knowledge, by redefining it anatomically, technologically, and philosophically. ^ He proceeds from the anatomical redefinition of the body in terms of the cir- culation of blood, to its technological resynthesis as a machine, only to ascertain its philosophical reduction to a material thing. Descartes's elaboration of the mind-body duahty will reinforce the autonomy of the body as a material thing, whose purely ob- jective and mechanical character will mark a fundamental depar- ture from previous humanist traditions. Decontextualized from its wordly fabric, the Cartesian body wUl cease to function by reference to the human, since its lived, experiential reality will be supplanted through mechanical analogues.^ Descartes's anatomical interpretation of the body in terms of the circulation of blood breaks away from earUer humoral con- ceptions of the body predominant into the early part of the sev- enteenth century. -

Dossier Exposition Louvre-Muséum D'histoire Naturelle

JUSQU’AU 15 OCTOBRE 2021 DOSSIER PÉDAGOGIQUE LIVRET 1 : L’EXPOSITION PIETER BOEL, LA MÉNAGERIE DE LOUIS XIV Musée du Louvre - Muséum d’Histoire naturelle de La Réunion Blesbok, Damalisque à front blanc Pieter Boel, Etudes de Bubale caama Damaliscus pygargus MHN Réu 2017-3 © Musée du Louvre ©Muséum d’Histoire naturelle Lorsque Louis XIV crée la Ménagerie royale, il offre un lieu de L’exposition « PIETER BOEL, La ménagerie de Louis XIV », est promenade et de curiosité très prisé du public. Souhaitant le fruit de la collaboration entre le Département de La Réunion conserver l’image des animaux exotiques réunis à Versailles il et le Musée du Louvre dans le cadre de la manifestation « Ré- fait appel à des artistes renommés, dont Pieter Boel (1622- sonances, le Louvre à La Réunion ». 1674), un peintre flamand installé à Paris. Reconnu pour le Elle bénéficie du label « Exposition d’intérêt national 2021». talent avec lequel il sait représenter les animaux, ce maître des sujets animaliers est tout particulièrement chargé de fournir les études pour la Manufacture des Gobelins. Démultipliant les COMMISSARIAT DE L’EXPOSITION détails anatomiques, les « expressions » et les attitudes, il Xavier Salmon, Conservateur général du Patrimoine, Directeur du Département des Arts graphiques du Musée du Louvre DU LOUVRE AU MUSÉUM DE LA RÉUNION Parmi les deux cents feuilles de Pieter Boel que détient le Mu- DOSSIER PÉDAGOGIQUE sée du Louvre, 29 dessins sont présentés au Muséum d’His- Sonia Ribes-Beaudemoulin, Co-commissaire de l’exposition toire naturelle. Ils illustrent des oiseaux (pélican, paon, au- Claude Eboué, Professeur relais au Muséum d'Histoire natu- truche, ara, canard, bernache, autour des palombes) et des relle et Professeur de SVT au Collège A. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/29/2021 04:24:58AM Via Free Access

journal of jesuit studies 5 (2018) 610-630 brill.com/jjs Moral Economy and the Jesuits Paola Vismara (†)* University of Milan Abstract In this article, originally published in French under the title “Les jésuites et la morale économique” (Dix-septième siècle 237, no. 4 [2007]: 739–54), Paola Vismara presents the Jesuits’ major contributions to the teaching of moral economy from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century. In particular, Vismara explores Jesuit doctrines on moral economy and focuses on various Jesuit approaches to the problems of contracts and the management of capital, with particular attention paid to lending at interest. Retracing the most significant early modern Jesuit theologians’ contributions to issues of moral economy, including the treatise of Leonard Lessius, Vismara paints a complex picture, highlighting the new ideas contained in the works of the Jesuit theologians, shedding light on disputes between probabilist and rigorist theologians, and discuss- ing the Roman Church’s responses to various theological orientations to moral econo- my over three centuries. Keywords Jesuits – Society of Jesus – usury – interest – extrinsic titles – vix pervenit – moral theology – triple contract – probabilism – rigorism Moral Economy within the Society of Jesus: An Introduction Early modern Jesuit doctrinal and theoretical reflections concerning matters of moral theology have always been the object of much attention because of their intellectual importance during the period, and because of the con- troversies they engendered. These reflections and their pastoral implications * The copyright of the original article in French is with the publisher Humensis, whom we thank for granting us permission to publish its English translation. © Paola vismara, 2018 | doi:10.1163/22141332-00504007 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the prevailing cc-by-nc license at the time of publication.