SIFU DANA WONG “IF YOU DON’T EMPTY YOUR GLASS, THERE IS NOTHING for YOU to LEARN” by Costas Argyriadis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ip Man from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Ip Man From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia [2] Ip Man, also known as Yip Man, (Chinese: 葉問; 1 October 1893 – 2 December 1972), was a Chinese martial artist, and a master Ip Man teacher of Wing Chun. He had several students who later became martial arts masters in their own right. His most famous student was Bruce Lee. Contents 1 Early life 2 Life in Hong Kong 3 Death and legacy 4 In popular culture 5 Martial arts lineage Born 1 October 1893 Foshan, 6 References Guangdong, Qing China Died 2 December 1972 Early life (aged 79) Mong Kok, Ip Man was born to Yip Oi-dor and Wu Shui. He grew up in a wealthy family in Foshan, Guangdong, and received a traditional Chinese Kowloon, Hong education. His elder brother was Yip Kai-gak, his elder sister was Yip Wan-mei and his younger sister was Yip Wan-hum.[3] Kong[1] Throat cancer [4][5] Ip started learning Wing Chun from Chan Wah-shun when he was 7. Chan was 64 at the time, and Ip became Chan's last student. Other Yip Man, Due to his teacher's age, Ip learned most of his skills and techniques from Chan's second eldest disciple, Wu Chung-sok (吳仲素). Chan names Yip Kai-man, lived three years after Ip's training started and one of his dying wishes was to have Wu continue teaching Ip. Ye Wen At the age of 16, Ip moved to Hong Kong with help from his relative Leung Fut-ting. One year later, he attended school at St. -

The Global Traditional Wing

THE GLOBAL TRADITIONAL WING CHUN KUNG FU ASSOCIATION Headquarters: Level 2, 111 Lonsdale Street, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia 3000 Tel: 61-3-9663 3588 Fax: 61-3-9663 3855 Email: [email protected] www.cheungswingchun.com FULL-TIME TRAINING IN MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA Full-time training is available at our Melbourne headquarters for people from around the world. Benefits of Full-time Training Full-time training allows practitioners to advance in their training of Wing Chun Kung Fu at a rapid rate. Because you are training intensively for several hours most days, your skills are developed and consolidated much more quickly than if you take just one or two lessons per week. If you wish to become an Instructor and eventually run a school under our Association in the city or town in which you live, full-time training will allow you to reach this goal. Full-time training is also beneficial to people who just want to add another dimension to their lives. Wing Chun Kung Fu is a way of life, builds self confidence, develops strong character, improves fitness, teaches self-defence skills, relieves stress and improves co-ordination and reflexes. It is an ancient art form that gives an insight into Chinese philosophy and history. The head of our Association, Wing Chun Grandmaster William Cheung, is eighth in the direct line of descendants from Wing Chun’s originator, Ng Mui. Grandmaster Cheung personally programs all classes at our Academy, and, when not on tour, is available for private lessons. (These are at an additional cost.) Training Information Full-time training includes: • unlimited classes at our Academy per week. -

Wing Chun Kung Fu/Jeet Kune Do: a Comparison, Volume 1, // William Cheung, Ted Wong // 1990

Wing Chun Kung Fu/jeet Kune Do: A Comparison, Volume 1, // William Cheung, Ted Wong // 1990 192 pages // William Cheung, Ted Wong // 1990 // Wing Chun Kung Fu/jeet Kune Do: A Comparison, Volume 1, // 0897501241, 9780897501248 // Black Belt Communications, 1990 // Bruce Lee’s original art (wing chun) and the art he developed (jeet kune do) are compared by Lee’s associates. Includes stances and footwork, hand and leg techniques, tactics, and self-defense. file download logewi.pdf Sifu Panayiotis Argyridis // Oct 12, 2010 // First, before I started writing my book, I considered that people would like to know the opposite. The reason for this is, most of the times we would really like to know and // 132 pages // The Principles Theories & Practice of Jun Fan Gung Fu/Jeet Kune Do, Volume 1 // ISBN:9781453506356 // Sports & Recreation ISBN:0897501187 // 255 pages // William Cheung, Mike Lee, Doug Churchill // 1988 // Sports & Recreation // Advanced Wing Chun // Learn to break down every stage of combat, from contact and exchange to pursuit and retreat, in this must-have manual that is filled with guiding principles, including chi sao pdf download Wing Chun Kung Fu/jeet Kune Do: A Comparison, Volume 1, pdf Bruce Lee // Sports & Recreation // Bruce Lee Jeet Kune Do is the seminal book presenting the martial art created by Bruce Lee himself as described in his own notes and writings. Jeet Kune Do was a revolutionary // 400 pages // Sep 8, 2015 // Bruce Lee Jeet Kune Do // ISBN:9781462917914 // Bruce Lee's Commentaries on the Martial Way Kung Wing Chun Kung Fu/jeet Kune Do: A Comparison, Volume 1, pdf file Ted Wong // 95 pages // Sports & Recreation // Bruce Lee Martial Arts Training Revealed // If you are interested in Karate, Taekwondo and other martial arts then this is the package for you. -

The World Wing Chun Kung Fu Association Presents

The Global Traditional Wing Chun Kung Fu Association presents Grandmaster William Cheung’s 2014 TEN YEAR ANNIVERSARY KUNG FU CHINA TOUR October 11 to 25, 2014 ITINERARY Beijing > Guilin > Xi’an > Luoyang > Dengfeng/Shaolin > Hong Kong Arrival Day Arrive in Beijing. Transfer from airport and check into 4 star Saturday Oct 11 Howard Johnson Paragon Hotel. Dinner in hotel restaurant and meet the rest of the group Day 1 Beijing: Sunday Oct 12 Breakfast in hotel. Option 1: Challenging 10km hike on the Great Wall from Jinshanling section to Gubeikou. On this isolated section of the Great Well, we won’t see tourists. Unlike the fully restored, busy Badaling section where we have been before, this section is rugged, steep and crumbling, but a good workout with breathtaking views and many many steps. Option 2: Visit both these sections of the Great Wall by bus, and sightsee. Packed lunch. Both groups meet up in the evening for a welcome dinner hosted by Grandmaster William Cheung. Day 2 Beijing / Guilin (Longshen) Monday Oct 13 Breakfast. Morning flight CA1311 at 7:15am followed by a full day excursion to Longsheng located in the mountainous region of the north eastern part of Guilin, and appreciate its natural beauty and colourful ethnic Chinese cultures and customs. Lunch After a 2.5 hour drive along the beautiful mountain road, we will arrive in Longji, Heping Township of Longsheng County to visit Zhuang and Yao minority tribes’ villages, as well as some families. We will see beautiful terraced rice fields after arriving at the summit of Longji (Dragon’s Backbone). -

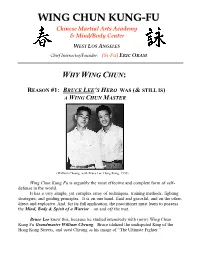

Wing Chun Kung-Fu

WWIINNGG CCHHUUNN KKUUNNGG--FFUU Chinese Martial Arts Academy & Mind/Body Center \ WEST LOS ANGELES Chief Instructor/Founder: (SI-FU) ERIC ORAM WHY WING CHUN: REASON #1: BRUCE LEE’S HERO WAS (& STILL IS) A WING CHUN MASTER (William Cheung, with Bruce Lee: Hong Kong, 1955) Wing Chun Kung Fu is arguably the most effective and complete form of self- defense in the world. It has a very simple, yet complex array of techniques, training methods, fighting strategies, and guiding principles. It is on one hand, fluid and graceful, and on the other, direct and explosive. And, for its full application, the practitioner must learn to possess the Mind, Body & Spirit of a Warrior – on and off the mat. Bruce Lee knew this, because he studied intensively with (now) Wing Chun Kung Fu Grandmaster William Cheung. Bruce idolized the undisputed King of the Hong Kong Streets, and used Cheung as his image of “The Ultimate Fighter.” 6 (Grandmaster William Cheung: Hong Kong, 1979) Grandmaster Cheung has lived on to become a true living legend in the martial arts world – and one of his top disciples, Si-Fu Eric Oram, now teaches this dynamic system out of the West Coast Headquarters in Los Angeles: the Wing Chun Kung Fu Academy & Mind/Body Center. (Si-Fu Oram: Great Wall, Northern China, 2004) Si-Fu Eric Oram is currently one of the world’s leading authorities on Wing Chun and is recognized as one of its best instructors, having taught the art worldwide under Master Cheung since 1985. Si-Fu Oram is also an actor, writer, and Fight Choreographer – and has applied the principles and benefits of wing chun far beyond its success on the mat and in the street. -

CMT Cheung's Meridian Therapy William Cheung

CMT Cheung's Meridian Therapy, 2002, William Cheung, 095805021X, 9780958050210, Cheung's Better Life, 2002 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1T0j5bd http://goo.gl/R4P8T http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CMT_Cheungs_Meridian_Therapy DOWNLOAD http://wp.me/2ozwn http://bit.ly/1nXi6jl Anatomical Atlas of Acupuncture Points , Zhen'guo Yan, 2003, Medical, 188 pages. This practical, full-color photographic atlas is an indispensable aid to rapid, accurate location of acupuncture points. It's the first book to combine illustrated acupuncture. Japan The Soul of a Nation, John Carroll, Michael S. Yamashita, Mar 1, 2003, History, 93 pages. The ancient traditions, breathtaking scenery and vibrant culture of Japan continue to fascinate the world. In this beautiful volume, renowned National Geographic photographer. Street Fighting Applications of Wing Chun No-Rules Rumble, William Cheung, Apr 1, 2009, Sports & Recreation, . With exciting stories of drama, combat, and intrigue from the streets of Sydney to the rooftops of Hong Kong, this DVD documents elements of kung fu grandmaster William Cheung. USMC A Complete History, Jon T. Hoffman, 2002, History, 656 pages. Published with the assistance of the U.S. Marine Corps, this sparkling, informative history of an elite fighting force chronicles 225 years of Marine activities, from major. Dynamic Chi Sao , William Cheung, 2006, Sports & Recreation, 226 pages. Chi sao drills constitute some of the most important training in the wing chun kung-fu system. While many chi sao techniques do not apply to actual combat, training in this. Wing Chun Bil Jee The Deadly Art of Thrusting Fingers, William Cheung, 1983, Sports & Recreation, 160 pages. William Cheung reveals the original wing chun bil jee form taught only to him by the late Yip Man. -

Bruce Lee As Method Daryl Joji Maeda

Nomad of the Transpacific: Bruce Lee as Method Daryl Joji Maeda American Quarterly, Volume 69, Number 3, September 2017, pp. 741-761 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2017.0059 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/670066 Access provided by University Of Colorado @ Boulder (19 Nov 2017 16:06 GMT) Bruce Lee as Method | 741 Nomad of the Transpacific: Bruce Lee as Method Daryl Joji Maeda The life of the nomad is the intermezzo. —Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari Be formless, shapeless, like water. —Bruce Lee he transpacific nomad Bruce Lee was born in San Francisco, raised in Hong Kong until the age of eighteen, came of age in Seattle, had his Thopes of movie stardom extinguished in Hollywood, and returned to Hong Kong to rekindle his dreams. In 1971 he made his first martial arts film, Tang Shan Daxiong, in which he played a Chinese immigrant to Thai- land who discovers that his boss is a drug-smuggling kingpin. The following year, he starred in Jing Wu Men as a martial artist who defends Chinese pride against Japanese imperialists in the International Settlement of early twentieth- century Shanghai. Because of the overwhelming popularity of both films in Hong Kong and throughout Asia, National General Pictures selected them for distribution in the United States in 1973. Tang Shan Daxiong was supposed to be released as The Chinese Connection to associate it with The French Con- nection, a mainstream hit about heroin trafficking; the title ofJing Wu Men was translated as Fist of Fury. -

2019 Class Timetable Cheung's Wing Chun Kung Fu Academy

2019 CLASS TIMETABLE CHEUNG’S WING CHUN KUNG FU ACADEMY Level 2, 111 Lonsdale Street, Melbourne Tel: 03-9663 3588 Email: [email protected] Self Defence & Fitness for Men – Women – Children Australia – USA – Canada – UK – France – Switzerland – Greece – China – Japan – Slovakia – Serbia – Croatia – Italy - Poland Grandmaster William Cheung: Yip Man’s student, Mentor to Bruce Lee President - The Global Traditional Wing Chun Kung Fu Association Combat Consultant to the US Navy Seals Instructors: Master Andrew Cheung, Sifu James Cheung, Sifu Damien Chauremootoo, Sifu Brendan Casey, Sifu Matt Fellows, Sifu Craig Barrow, Sifu Daniel Sapsead, www.cheungswingchun.com Keep up-to-date with class, seminar and special event information: “Like” our Facebook page – Cheung’s Wing Chun Kung Fu Academy - Melbourne Monday 12 noon – 1:30pm All Levels 4:00pm to 5:00pm All Levels 5:30pm to 6:45pm All Levels 7:00pm to 8:30pm All Levels Tuesday 12 noon – 1:30pm All Levels 4:00pm to 5:00pm All Levels 5:30pm to 6:45pm All Levels 5:30pm to 6:30pm Women’s Self Defence Course 7:00pm to 8:30pm All Levels Wednesday 12 noon – 1:30pm All Levels 4:00pm to 5:00pm All Levels 5:30pm to 6:30pm Free Beginner Class 7:00pm to 8:30pm All Levels Thursday 12 noon – 1:30pm All Levels 4:00pm to 5:00pm All Levels 5:30pm to 6:45pm All Levels “Traditional Wing Chun Kung 7:00pm to 8:30pm Advanced class Fu is based on science: All Friday Closed other martial arts can only fight front-on, therefore the Saturday 9:30am to 10:15am Children Level 3 and above bigger and faster fighter must 10:15am to 11:00am Children - Beginners win. -

The History and Philosophy of Wing Chun Kung Fu Thesis for Level Ten Grading Andrew Nerlich Student of Sifu Rick Spain, WWCKFA

The History and Philosophy of Wing Chun Kung Fu Thesis for Level Ten Grading Andrew Nerlich student of Sifu Rick Spain, WWCKFA. History In the Beginning... The deep nature of our own species, and those that preceded us in evolution, includes competition, violence, and killing. Prehistoric men no doubt fought one another for dominance, food, mating rights, and survival. The dawn of a structured or scientific approach to fighting no doubt occurred with the first primitive man to pick up a stick with which to strike an enemy or prey. Conflict and warfare form pivotal events in human history. Arguably, many ancient rituals, sports and ceremonies are reenactments of battles in one form or another. The Olympic Games held by the ancient Greeks were regarded as a religious festival, during which war was suspended. The Epic of Gilgamesh, written down in about the eighteenth century B.C. in Mesopotamia, one of the earliest centres of civilisation, shows that most weapons of war had been invented by then, the major exception being explosives, which were to be invented by the Chinese almost 2800 years later. Gilgamesh, a hero of Uruk in Babylonia, fought with axe, sword, bow and arrow, and spear. His contemporaries used battering rams against enemy cities, and rode to battle in chariots. The concept of a martial art or science of combat no doubt developed along with civilisation. Organised warfare required trained and disciplined soldiers, and generals and instructors to command and train them. The earliest accepted evidence of a martial art exists in two small Babylonian works of art dating back to between 2000 and 3000 B.C., each showing two men in postures of combat. -

The Bruce Lee TRAINING SECRET by Grandmaster William Cheung

The Bruce Lee TRAINING SECRET by Grandmaster William Cheung (Australasian Blitz Magazine) Every martial artist would like to know how and what made Bruce Lee such a devastating fighter. Even though a lot of people associated with Bruce Lee or many claimed to have trained him or trained with him, I can safely say that not many of them were privileged to his secret training method. Bruce and I grew up together. We were friends since we were young boys. It was I who introduced Bruce Lee to Wing Chun School in the summer of 1954. In the old days, the master would never teach the new students. It was up to the senior students to pass on the Wing Chun lessons to Bruce. As I was his Kung Fu Senior of many years, I was instructed by Grandmaster Yip man to train him. By 1995, one year into his Wing Chun training, Bruce progressed very fast, and already became a threat to most of the Wing Chun seniors as the majority of them were armchair martial artists. They discovered that Bruce was not a full blooded Chinese because his mother was half German and half Chinese. The seniors got together and put pressure on Professor Yip Man and tried to get Bruce kicked out of the Wing Chun School. Because racism was widely practised in Martial Arts School in Hong Kong, the art was not allowed to be taught to foreigners. Professor Yip Man had no other choice but to bow to their pressure, but he told Bruce that he could train with me and Sihing Wong Shun Leung. -

Downloaded on 22 May 2018

CONSERVATION PRIORITIZATION AND ECOLOGY OF DATA- POOR MARINE SPECIES UNDER HUMAN PRESSURES by Xiong Zhang B.S., Chongqing University, 2010 M.Sc., The University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2013 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Zoology) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) January 2019 © Xiong Zhang, 2019 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, the dissertation entitled: Conservation Prioritization and Ecology of Data-poor Marine Species under Human Pressures submitted by Xiong Zhang in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (Zoology) Examining Committee: Dr. Amanda Vincent Supervisor Dr. William Cheung Supervisory Committee Member Dr. Tara Martin University Examiner Dr. Mary O’Connor University Examiner Additional Supervisory Committee Members: Dr. Christopher Harley Supervisory Committee Member Dr. Sarah Gergel Supervisory Committee Member ii Abstract Securing a healthy and biodiverse ocean is vital to our human wellbeing. However, marine conservation is challenging, especially for data-poor species, whose habitats and threats are understudied. My dissertation explored how to address such challenges at two large spatial scales (in China and globally), with a focus on the little studied seahorses (Hippocampus spp.). In the first two data chapters, I explored the utility of various sources of information about species and habitat covariates in species distribution models (SDMs). My results from the first chapter showed that local ecological knowledge provided useful biogeographic data of five Chinese seahorse species to predict their distributions, which were mainly associated with ocean temperature. -

Feb 2011 Newletter

THE TRADITIONAL WING CHUN NEWS LETTER This is a story like any would seem too good to William Cheung. In great action movie. Full of be true but that’s what creating this article it was drama, pain and survival, makes the tale of Grand painful deciding which gangsters and street Master William Cheung so parts to include and fighters, and at the intriguing. Now in his which to omit but centre of the story is the sixties there are hopefully what follows is hero. Some of the parts hundreds of tales as entertaining to read as that make up this story surrounding the life of it is to hear firsthand. I met William Cheung for the first time inside his Chinatown training gym, tucked away at the end of an alleyway and up a flight of stairs. Dozens of framed magazine covers featuring William Cheung in various Wing Chun stances adorn the walls of the stairwell as I make my way into the gym where I am greeted by an enthusiastic William Cheung. Although in his mid-sixties, William appears to be very fit and strides with confidence as he leads me into his upstairs training room where we sit down in front of a row of trophies from various martial arts tournaments. William is friendly and more than keen to share his story. Beginning with his early childhood, William explains the path that led him into the martial arts world. “My father had two wives, which was very common in those days and I was the son of the second wife.