1 Submissions for the 2020-2021 Policy Address

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Controlling Officer's Reply

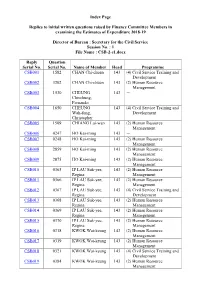

Index Page Replies to initial written questions raised by Finance Committee Members in examining the Estimates of Expenditure 2018-19 Director of Bureau : Secretary for the Civil Service Session No. : 1 File Name : CSB-2-e1.docx Reply Question Serial No. Serial No. Name of Member Head Programme CSB001 1582 CHAN Chi-chuen 143 (4) Civil Service Training and Development CSB002 3202 CHAN Chi-chuen 143 (2) Human Resource Management CSB003 1530 CHEUNG 143 - Chiu-hung, Fernando CSB004 1650 CHEUNG 143 (4) Civil Service Training and Wah-fung, Development Christopher CSB005 1509 CHIANG Lai-wan 143 (2) Human Resource Management CSB006 0247 HO Kai-ming 143 - CSB007 0248 HO Kai-ming 143 (2) Human Resource Management CSB008 2859 HO Kai-ming 143 (2) Human Resource Management CSB009 2875 HO Kai-ming 143 (2) Human Resource Management CSB010 0365 IP LAU Suk-yee, 143 (2) Human Resource Regina Management CSB011 0366 IP LAU Suk-yee, 143 (2) Human Resource Regina Management CSB012 0367 IP LAU Suk-yee, 143 (4) Civil Service Training and Regina Development CSB013 0368 IP LAU Suk-yee, 143 (2) Human Resource Regina Management CSB014 0369 IP LAU Suk-yee, 143 (2) Human Resource Regina Management CSB015 0370 IP LAU Suk-yee, 143 (2) Human Resource Regina Management CSB016 0318 KWOK Wai-keung 143 (2) Human Resource Management CSB017 0319 KWOK Wai-keung 143 (2) Human Resource Management CSB018 0321 KWOK Wai-keung 143 (4) Civil Service Training and Development CSB019 0384 KWOK Wai-keung 143 (2) Human Resource Management Reply Question Serial No. Serial No. Name of Member -

As at Early February 2012)

Annex Government Mobile Applications and Mobile Websites (As at early February 2012) A. Mobile Applications Name Departments Tell me@1823 Efficiency Unit Where is Dr Sun? Efficiency Unit (youth.gov.hk) Youth.gov.hk Efficiency Unit (youth.gov.hk) news.gov.hk Information Services Department Hong Kong 2010 Information Services Department This is Hong Kong Information Services Department Nutrition Calculator Food and Environmental Hygiene Department Snack Nutritional Classification Wizard Department of Health MyObservatory Hong Kong Observatory MyWorldWeather Hong Kong Observatory Hongkong Post Hongkong Post RTHK On The Go Radio Television Hong Kong Cat’s World Radio Television Hong Kong Applied Learning (ApL) Education Bureau HKeTransport Transport Department OFTA Broadband Performance Test Office of the Telecommunications Authority Enjoy Hiking Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department Hong Kong Geopark Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department Hong Kong Wetland Park Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department Reef Check Hong Kong Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department Quit Smoking App Department of Health Build Up Programme Development Bureau 18 Handy Tips for Family Education Home Affairs Bureau Interactive Employment Service Labour Department Senior Citizen Card Scheme Social Welfare Department The Basic Law Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau B. Mobile Websites Name Departments Tell me@1823 Website Efficiency Unit http://mf.one.gov.hk/1823mform_en.html Youth.gov.hk Efficiency Unit http://m.youth.gov.hk/ -

Clinical Legal Education in Hong Kong: a Time to Move Forward Stacy Caplow Brooklyn Law School, [email protected]

Brooklyn Law School BrooklynWorks Faculty Scholarship 2006 Clinical Legal Education in Hong Kong: A Time to Move Forward Stacy Caplow Brooklyn Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/faculty Part of the Legal Education Commons, and the Other Law Commons Recommended Citation 36 Hong Kong L. J. 229 (2006) This Response or Comment is brought to you for free and open access by BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of BrooklynWorks. COMMENT CLINICAL LEGAL EDUCATION IN HONG KONG: A TIME TO MOVE FORWARD Introduction Clinical education has taken root and flourished in law schools throughout the world. Although initially a United States phenomenon, universities in countries as far-flung as India, South Africa, Chile, Australia, Poland, Scotland, Cambodia, Mexico, and China have established and nurtured clinical programmes. Despite different legal systems and different institutional structures, law faculties in these disparate countries all share a respect for the potential of clinical legal education. They recognise that clinical programmes can teach law students the skills and values of the profession while contributing vital services to individuals and communities and foster- ing social justice goals. The priorities of clinical programmes may differ from school to school, and the organisation and ambitions of their respective programmes may vary, yet law schools throughout the world have found common ground in the basic characteristics that define clinical legal education. Law schools in Hong Kong have no clinical programmes - yet. This situation may change as a result of a recent initiative by the Faculty of Law at Hong Kong University (HKU). -

Panel on Administration of Justice and Legal Services

For discussion on 23 October 2017 Legislative Council Panel on Administration of Justice and Legal Services The Chief Executive’s 2017 Policy Address Policy Initiatives of the Home Affairs Bureau INTRODUCTION This paper briefs Members on the policy initiatives in respect of legal aid and free legal advice services in the Chief Executive’s 2017 Policy Address (“Policy Address”) and Policy Agenda. OUR VISION 2. Legal aid services form an integral part of the legal system in Hong Kong. We strive to ensure the accessibility of legal aid and free legal advice services to the public to contribute towards upholding the value of everyone being equal before the law. NEW INITIATIVES Transfer of the Legal Aid Portfolio 3. As announced in the Policy Address, following the recommendations of the Legal Aid Services Council (“LASC”) and taking into account views from stakeholders, the Chief Executive has decided to transfer the responsibilities for formulating legal aid policy and housekeeping the Legal Aid Department (“LAD”) from the Home Affairs Bureau (“HAB”) to the Chief Secretary for Administration’s Office. The transfer will take effect after the necessary approval has been obtained from the Legislative Council (“LegCo”). Review of Duty Lawyer Fees 4. The Government has decided to conduct a review of duty lawyer fees and will set up a working group for the purpose. We have invited the two legal professional bodies, the Duty Lawyer Service (“DLS”) and relevant government departments, namely the Department of Justice and LAD, to join the working group. Upon completion of the review, the Government will report the outcome to this Panel. -

247/20-21(01)號文件 LC Paper No. CB(2)247/20-21(01)

立法會CB(2)247/20-21(01)號文件 LC Paper No. CB(2)247/20-21(01) Submissions to the Legislative Council Panel on Constitutional Affairs’ Meeting on 16 November 2020 Agenda item IV Hearing of the United Nations Human Rights Committee on the Fourth Report of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region in the light of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1. Introduction Justice Centre Hong Kong appreciates this opportunity to provide comments on the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (“Hong Kong”)’s fourth review under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (“ICCPR”). In May 2020, Justice Centre submitted a civil society report to the United Nations Human Rights Committee with a focus on the ICCPR’s application in the migration context1. Justice Centre’s report details our concerns with the Unified Screening Mechanism, the Government’s asylum policy, immigration detention and the lack of protection for victims of human trafficking in all its forms. In August 2020 the Human Rights Committee released a List of Issues (“LoI”), in which most of the issues raised in Justice Centre’s report were adopted: see paragraphs 12 - 162. We reproduce our report to the Human Rights Committee below with updated statistics and other relevant developments since May 2020. We hope this information will assist the Hong Kong Government in preparing concrete answers to the Human Rights Committee’s List of Issues and engaging constructively in the review process. 2. Developments in Hong Kong’s protection landscape since 2013 There have been significant policy and legal changes in Hong Kong’s protection landscape since the Human Rights Committee last reviewed Hong Kong in 2013. -

Hong Kong Dollar (HK$) Which Is Accepted As Currency in Macau

Interesting & Fun Facts About Macau . The official name of Macau is Macau Special Administrative Region. The official languages of Macau are Portuguese and Chinese. Macau lies on the western side of the Pearl River Delta, bordering Guangdong province in the north. Majority of the people living in Macau are Buddhists, while one can also find Roman Catholics and Protestants here. The economy of Macau largely depends upon the revenue generated by tourism. Gambling is also a money-generating affair in the region. The currency of Macau is Macanese Pataca. After Las Vegas, Macau is one of the biggest gambling areas in the world. In fact, gambling is even legalized in Macau. Macau is the Special Administrative Region of China. It is one of the richest cities in the world. Colonized by the Portuguese in the 16th century, Macau was the first European settlement in the Far East. Macau is one of the most densely populated regions in the world. Macau ranks amongst the top 10 regions in the world, with a quite high life expectancy at birth. Macau is a highly humid region, with the humidity ranging anywhere between 75% and 90%. It receives fairly heavy rainfall as well. The Historic Centre of Macau, including twenty-five historic monuments and public squares, is listed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. The tourists of Macau should know that tipping is a very popular as well as important tradition followed in the region. Nearly 10% of the bill is given as tip in most of the restaurants and hotels of Macau http://goway.com/blog/2010/06/25/interesting-fun-facts-about-macau/ Basic Information on Macao (east-asian-games2005.com) Updated: 2005-09-27 15:23 Geographical Location Macau is located in the Guangdong province,on western bank of the Pearl River Delta,at latitude 22o14‘ North,longitude 133 o35‘ East and connected to the Gongbei District by the Border Gate (Portas do Cerco) isthmus. -

Cb(4)240/17-18(04)

CB(4)240/17-18(04) For discussion on 27 November 2017 Legislative Council Panel on Administration of Justice and Legal Services Transfer of Legal Aid Portfolio PURPOSE This paper briefs Members on the proposed transfer of the legal aid portfolio from the Home Affairs Bureau (“HAB”) to the Chief Secretary for Administration’s Office (“CSO”), including the consequential changes to the two offices. BACKGROUND 2. As announced in the Chief Executive (“CE”)’s 2017 Policy Address, the Government will, as part of its restructuring initiatives, implement the Legal Aid Services Council1 (“LASC”)’s earlier proposal to transfer the responsibilities for formulating legal aid policy and housekeeping LAD from HAB to CSO, thereby underlining the independence of the legal aid system. 3. LASC recommended, among other things, that LAD should be re-positioned and made directly accountable to the Chief Secretary for Administration (“CS”), which had been the arrangement prior to July 2007. After careful assessment of LASC’s recommendations and taking into account views from stakeholders, the Government reported to the Panel on Administration of Justice and Legal Services in June 2014 its decision to accept in principle LASC’s recommendation that the responsibilities for formulating legal aid policy and housekeeping LAD should be vested with CSO and the Director of Legal Aid (“DLA”) should report directly to CS. 1 LASC is a statutory body set up in 1996 under the Legal Aid Services Council Ordinance (Cap. 489) to oversee the administration of legal aid services provided by LAD and advise CE on legal aid policy. THE PROPOSAL Transfer of Posts 4. -

Way – Finding Community Legal Assistance in Hong Kong Non-Governmental Organisations 42 Law Firm Pro Bono 42 Part II: Key Observations 43

CONTENT Foreword: Finding Pro Bono Legal Help in Hong Kong 5 Foreword: A “Rolls Royce” Legal System in Hong Kong? 6 Purpose of this Report 8 Scope of this Report 8 Methodology 9 Abbreviations and Glossary 11 Executive Summary 13 PART I: MEASURING THE LEGAL NEEDS 16 Introduction 18 Past Reviews of Access to Justice 18 This Legal Needs Assessment 19 Findings 20 NGO Surveys 20 SoCO Surveys and Interviews 22 Part I: Key Observations 24 PART II: EXISTING FREE OR SUBSIDISED LEGAL SERVICES 25 Introduction 27 A Brief History of Free or Subsidised Legal Services 27 Current Situation: Who Provides Free or Subsidised Legal Services to the Community? 28 Legal Aid Department 28 The Duty Lawyer Service 32 Duty Lawyer Scheme 32 Free Legal Advice Scheme 33 CAT & Non-Refoulement Claims Scheme 35 Free Legal Advice Scheme at the University of Hong Kong 35 Procedural Advice Scheme 36 Resource Centre for Unrepresented Litigants 37 Bar Free Legal Services Scheme 37 Law Society of Hong Kong’s Pro Bono Services 38 Equal Opportunities Commission 39 Consumer Legal Action Fund 40 Office of Legislative and District Councillors 41 02 | This Way – Finding Community Legal Assistance in Hong Kong Non-Governmental Organisations 42 Law Firm Pro Bono 42 Part II: Key Observations 43 PART III: REGULATORY ISSUES 45 Introduction 47 How to do Pro Bono as a Solicitor 47 How to do Pro Pono as a Foreign-Qualified Lawyer 49 How to do Pro Bono as a Barrister 49 How to do Pro Bono as an In-House Counsel 49 How to do Pro Bono as a Law Student 50 How to Provide Free Legal Service to -

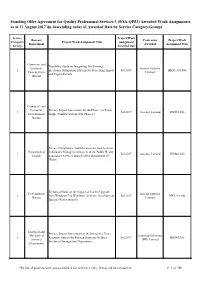

SOA-QPS3) Awarded Work Assignments As at 31 August 2017 (In Descending Order of Awarded Date by Service Category/Group

Standing Offer Agreement for Quality Professional Services 3 (SOA-QPS3) Awarded Work Assignments as at 31 August 2017 (in descending order of Awarded Date by Service Category/Group) Service Project/Work Bureau/ Contractor Project/Work Category/ Project/Work Assignment Title Assignment Department Awarded Assignment Price Group Awarded Date Commerce and Feasibility Study on Integrating Six Existing Economic Kinetix Systems 1 Electronic Submission Systems for Processing Import Jul 2017 HK$3,101,000 Development Limited and Export Permits Bureau Commerce and Economic Privacy Impact Assessment for the Phase 1 of Trade 1 Jul 2017 Arcotect Limited HK$53,300 Development Single Window System (SW Phase 1) Bureau Privacy Compliance Audit Services for the Electronic Department of Laboratory Management System of the Public Health 1 Jul 2017 Arcotect Limited HK$46,640 Health Laboratory Services Branch of the Department of Health Technical Study on the Impact of System Upgrade Development Kinetix Systems 1 from Windows 7 to Windows 10 for the Development Jul 2017 HK$264,400 Bureau Limited Bureau (Works Branch) Electrical and Privacy Impact Assessment of the Interactive Voice Mechanical Automated Systems 1 Response System for Foreign Domestic Helpers Jul 2017 HK$45,986 Services (HK) Limited Section of Immigration Department Department The list of projects/work assignments is for reference only. It may not be exhaustive. P. 1 of 289 Standing Offer Agreement for Quality Professional Services 3 (SOA-QPS3) Awarded Work Assignments as at 31 August 2017 (in -

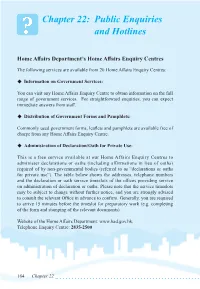

Chapter 22: Public Enquiries and Hotlines

Chapter 22: Public Enquiries and Hotlines Home Affairs Department’s Home Affairs Enquiry Centres The following services are available from 20 Home Affairs Enquiry Centres: u Information on Government Services: You can visit any Home Affairs Enquiry Centre to obtain information on the full range of government services. For straightforward enquiries, you can expect immediate answers from staff. u Distribution of Government Forms and Pamphlets: Commonly used government forms, leaflets and pamphlets are available free of charge from any Home Affairs Enquiry Centre. u Administration of Declaration/Oath for Private Use: This is a free service available at our Home Affairs Enquiry Centres to administer declarations or oaths (including affirmations in lieu of oaths) required of by non-governmental bodies (referred to as “declarations or oaths for private use”). The table below shows the addresses, telephone numbers and the declaration or oath service timeslots of the offices providing service on administration of declaration or oaths. Please note that the service timeslots may be subject to change without further notice, and you are strongly advised to consult the relevant Office in advance to confirm. Generally, you are required to arrive 15 minutes before the timeslot for preparatory work (e.g. completing of the form and stamping of the relevant documents). Website of the Home Affairs Department: www.had.gov.hk. Telephone Enquiry Centre: 2835-2500 164 Chapter 22 Home Affairs Enquiry Centres Home Affairs Address Telephone Declaration/ Enquiry -

Page No. Original Revised 8 There Are at Present 87 There Are at Present 88 2Nd Column, Line 7 Departmental Consultative Departmental Consultative Committees

Updates Guide on Staff Relations Please note the following updates: Page No. Original Revised 8 There are at present 87 There are at present 88 2nd column, line 7 Departmental Consultative Departmental Consultative Committees. Committees. 10 1st column, line 13 http://www.hku.hk/hkgcsb http://www.csb.gov.hk 15 CSB Circular No. 15/91 2nd column, line 6 Consultative Machinery Circular lapsed in the Civil Service 15 CSB Circular Memo No. CSB Circular No. 7/2001 2nd column, line 15 5/95 Guidelines for Handling Guidelines for Handling Sexual Harassment Sexual Harassment Complaints in the Civil Complaints in the Civil Service Service 16 1st column, line 6 http://www.hku.hk/hkgcsb http://www.csb.gov.hk 16 CSB Circular No. 5/99 CSB Circular No. 6/2001 1st column, line 9 Holiday Homes for Holiday Homes for Government Officers Government Officers Subject Officer Schedule of Bureaux / Departments Senior Executive Officer Chief Secretary for Administration’s Office (Staff Relations)1 Financial Secretary’s Office Tel 2810 3050 Education and Manpower Bureau Finance Bureau Health and Welfare Bureau Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department Civil Aviation Department Companies Registry Department of Health Education Department Judiciary Department of Justice Legal Aid Department Land Registry Official Receiver’s Office Rating and Valuation Department Student Financial Assistance Agency Social Welfare Department University Grants Committee Secretariat P.21 (Rev. 11/2001) Subject Officer Schedule of Bureaux / Departments Senior Executive Officer -

International Human Rights Instruments

UNITED NATIONS HRI International Distr. GENERAL Human Rights HRI/CORE/1/Add.62 Instruments 24 January 1996 ENGLISH ONLY CORE DOCUMENT FORMING PART OF THE REPORTS OF STATES PARTIES OVERSEAS DEPENDENT TERRITORIES AND CROWN DEPENDENCIES OF THE UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND [14 September 1995] CONTENTS Page Introduction ............................. 2 Annexes I. Anguilla............................ 3 II. Bermuda ............................ 12 III. British Virgin Islands..................... 24 IV. Cayman Islands......................... 31 V. Falkland Islands........................ 38 VI. Gibraltar ........................... 52 VII. Hong Kong ........................... 64 VIII. Montserrat........................... 78 IX. Pitcairn............................ 85 X. St. Helena........................... 89 XI. Turks and Caicos Islands.................... 96 XII. Isle of Man .......................... 104 XIII. Bailiwick of Jersey ...................... 110 XIV. Bailiwick of Guernsey ..................... 125 GE.96-15372 (E) HRI/CORE/1/Add.62 page 2 Introduction 1. In accordance with the consolidated guidelines for the initial part of the reports of States Parties (HRI/1991/1) which was transmitted under cover of the Secretary-General’s Note dated 26 April 1991 (HRI/CORE/1), the Government of the United Kingdom submits, annexed herewith, the core document (the "country profile") in respect of: (i) Each of its Dependent Territories overseas to which one or more of the various United Nations human rights treaties applies, that is to say, Anguilla, Bermuda, the British Virgin Islands, the Cayman Islands, the Falkland Islands, Gibraltar, Hong Kong, Montserrat, Pitcairn, St. Helena and the Turks and Caicos Islands (annexes I-XI). (ii) Each of its Crown Dependencies to which one or more of those treaties applies, that is to say, the Isle of Man, Guernsey and Jersey (annexes XII-XIV).