The Government Minute in Response to the Annual Report of the Ombudsman 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Controlling Officer's Reply

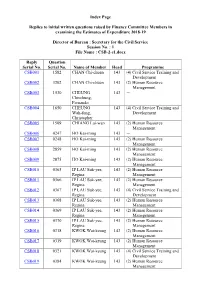

Index Page Replies to initial written questions raised by Finance Committee Members in examining the Estimates of Expenditure 2018-19 Director of Bureau : Secretary for the Civil Service Session No. : 1 File Name : CSB-2-e1.docx Reply Question Serial No. Serial No. Name of Member Head Programme CSB001 1582 CHAN Chi-chuen 143 (4) Civil Service Training and Development CSB002 3202 CHAN Chi-chuen 143 (2) Human Resource Management CSB003 1530 CHEUNG 143 - Chiu-hung, Fernando CSB004 1650 CHEUNG 143 (4) Civil Service Training and Wah-fung, Development Christopher CSB005 1509 CHIANG Lai-wan 143 (2) Human Resource Management CSB006 0247 HO Kai-ming 143 - CSB007 0248 HO Kai-ming 143 (2) Human Resource Management CSB008 2859 HO Kai-ming 143 (2) Human Resource Management CSB009 2875 HO Kai-ming 143 (2) Human Resource Management CSB010 0365 IP LAU Suk-yee, 143 (2) Human Resource Regina Management CSB011 0366 IP LAU Suk-yee, 143 (2) Human Resource Regina Management CSB012 0367 IP LAU Suk-yee, 143 (4) Civil Service Training and Regina Development CSB013 0368 IP LAU Suk-yee, 143 (2) Human Resource Regina Management CSB014 0369 IP LAU Suk-yee, 143 (2) Human Resource Regina Management CSB015 0370 IP LAU Suk-yee, 143 (2) Human Resource Regina Management CSB016 0318 KWOK Wai-keung 143 (2) Human Resource Management CSB017 0319 KWOK Wai-keung 143 (2) Human Resource Management CSB018 0321 KWOK Wai-keung 143 (4) Civil Service Training and Development CSB019 0384 KWOK Wai-keung 143 (2) Human Resource Management Reply Question Serial No. Serial No. Name of Member -

As at Early February 2012)

Annex Government Mobile Applications and Mobile Websites (As at early February 2012) A. Mobile Applications Name Departments Tell me@1823 Efficiency Unit Where is Dr Sun? Efficiency Unit (youth.gov.hk) Youth.gov.hk Efficiency Unit (youth.gov.hk) news.gov.hk Information Services Department Hong Kong 2010 Information Services Department This is Hong Kong Information Services Department Nutrition Calculator Food and Environmental Hygiene Department Snack Nutritional Classification Wizard Department of Health MyObservatory Hong Kong Observatory MyWorldWeather Hong Kong Observatory Hongkong Post Hongkong Post RTHK On The Go Radio Television Hong Kong Cat’s World Radio Television Hong Kong Applied Learning (ApL) Education Bureau HKeTransport Transport Department OFTA Broadband Performance Test Office of the Telecommunications Authority Enjoy Hiking Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department Hong Kong Geopark Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department Hong Kong Wetland Park Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department Reef Check Hong Kong Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department Quit Smoking App Department of Health Build Up Programme Development Bureau 18 Handy Tips for Family Education Home Affairs Bureau Interactive Employment Service Labour Department Senior Citizen Card Scheme Social Welfare Department The Basic Law Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau B. Mobile Websites Name Departments Tell me@1823 Website Efficiency Unit http://mf.one.gov.hk/1823mform_en.html Youth.gov.hk Efficiency Unit http://m.youth.gov.hk/ -

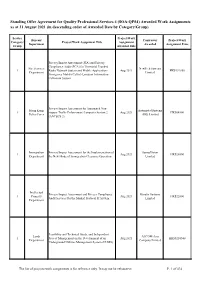

SOA-QPS4) Awarded Work Assignments As at 31 August 2021 (In Descending Order of Awarded Date by Category/Group)

Standing Offer Agreement for Quality Professional Services 4 (SOA-QPS4) Awarded Work Assignments as at 31 August 2021 (in descending order of Awarded Date by Category/Group) Service Project/Work Bureau/ Contractor Project/Work Category/ Project/Work Assignment Title Assignment Department Awarded Assignment Price Group Awarded Date Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA) and Privacy Compliance Audit (PCA) for Terrestrial Trunked Fire Services NewTrek Systems 1 Radio Network System and Mobile Application - Aug 2021 HK$192850 Department Limited Emergency Mobile Caller's Location Information Collection System Privacy Impact Assessment for Automated Non- Hong Kong Automated Systems 1 stopper Traffic Enforcement Computer System 2 Aug 2021 HK$64500 Police Force (HK) Limited (ANTECS 2) Immigration Privacy Impact Assessment for the Implementation of SunnyVision 1 Aug 2021 HK$28000 Department the New Mode of Immigration Clearance Operation Limited Intellectual Privacy Impact Assessment and Privacy Compliance Kinetix Systems 1 Property Aug 2021 HK$22800 Audit Services for the Madrid Protocol IT System Limited Department Feasibility and Technical Study, and Independent Lands AECOM Asia 1 Project Management on the Development of an Aug 2021 HK$5210540 Department Company Limited Underground Utilities Management System (UUMS) The list of projects/work assignments is for reference only. It may not be exhaustive. P. 1 of 434 Standing Offer Agreement for Quality Professional Services 4 (SOA-QPS4) Awarded Work Assignments as at 31 August 2021 (in descending order -

City University of Hong Kong Continued to Make Significant Progress in Many Areas of Knowledge Transfer

Annual Report on Knowledge Transfer for 2017-2018 to University Grants Committee Table of Contents Page Executive Summary 1 1. Fostering Technology Transfer 2 2. Broadening Knowledge Transfer beyond Science and Engineering Disciplines 4 3. Upholding Research Excellence 4 4. Expanding Research Platform and Technology Transfer to the Mainland 5 5. Nurturing Inno-preneurship Ecosystem 6 6. Impact Cases 8 Appendix 1 – Summary of Knowledge Transfer Performance Indicators 12 Appendix 2 – Patents Filed 14 Appendix 3 – Patents Granted 15 Appendix 4 – Economically Active Spin-off Companies 16 Appendix 5 – Knowledge Transfer in College of Business 17 Appendix 6 – Knowledge Transfer in College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 20 Appendix 7 – Knowledge Transfer in College of Science and Engineering 23 Appendix 8 – Knowledge Transfer in College of Veterinary Medicine and Life 28 Sciences Appendix 9 – Knowledge Transfer in School of Creative Media 29 Appendix 10 – Knowledge Transfer in School of Energy and Environment 31 Appendix 11 – Knowledge Transfer in School of Law 32 Executive Summary In the reporting period, City University of Hong Kong continued to make significant progress in many areas of knowledge transfer. First and foremost is the soaring licensing income of over HK$18m, second highest obtained so far. City University has continued to strengthen technology transfer partnership with leading universities worldwide, so that a much larger and more comprehensive portfolio of technology solutions can benefit the University’s own technology marketing efforts. On the market development side, we have expanded our reach into inland market, establishing new relationships with inland government agencies. Partnership and collaboration with local and international industrialists, trade and commerce organizations, and innovation and research bodies have been a core commitment of City University in upholding its applied research and technology transfer endeavours. -

Food Safety, Environmental Hygiene, Agriculture and Fisheries

180 Chapter 9 Food Safety, Environmental Hygiene, Agriculture and Fisheries Hong Kong imports some 95 per cent of its foodstuffs. It has in place a wide array of measures to ensure foods are safe for consumption. Environmental hygiene is also a round-the-clock undertaking to promote public health and to raise the standard of living. Organisational Framework The Food and Health Bureau is responsible for drawing up policies on food safety, environmental hygiene, animal health, and matters concerning agriculture and fisheries in Hong Kong. It also allocates resources for carrying out these policies. In the areas of food safety and environmental hygiene, the bureau works closely with two departments: the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department (FEHD) and the Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department (AFCD). The FEHD is tasked with ensuring that food in Hong Kong is safe for consumption and that environmental hygiene standards are high. The AFCD is responsible for implementing policies governing the agricultural and fishery industries and for helping them to stay competitive by providing them with infrastructural and technical support such as market facilities and animal disease diagnostic services. The department also administers loans to them and advises the Government on veterinary matters. Public Cleansing Services The FEHD provides services for street cleansing, household waste collection and public toilets. Streets in all urban and rural areas are swept manually, sometimes eight times a day, depending on the area’s needs. For main thoroughfares, flyovers and high speed roads, mechanised cleansing is provided. About 64 per cent of street cleansing services were outsourced to private contractors in 2007. -

Clinical Legal Education in Hong Kong: a Time to Move Forward Stacy Caplow Brooklyn Law School, [email protected]

Brooklyn Law School BrooklynWorks Faculty Scholarship 2006 Clinical Legal Education in Hong Kong: A Time to Move Forward Stacy Caplow Brooklyn Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/faculty Part of the Legal Education Commons, and the Other Law Commons Recommended Citation 36 Hong Kong L. J. 229 (2006) This Response or Comment is brought to you for free and open access by BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of BrooklynWorks. COMMENT CLINICAL LEGAL EDUCATION IN HONG KONG: A TIME TO MOVE FORWARD Introduction Clinical education has taken root and flourished in law schools throughout the world. Although initially a United States phenomenon, universities in countries as far-flung as India, South Africa, Chile, Australia, Poland, Scotland, Cambodia, Mexico, and China have established and nurtured clinical programmes. Despite different legal systems and different institutional structures, law faculties in these disparate countries all share a respect for the potential of clinical legal education. They recognise that clinical programmes can teach law students the skills and values of the profession while contributing vital services to individuals and communities and foster- ing social justice goals. The priorities of clinical programmes may differ from school to school, and the organisation and ambitions of their respective programmes may vary, yet law schools throughout the world have found common ground in the basic characteristics that define clinical legal education. Law schools in Hong Kong have no clinical programmes - yet. This situation may change as a result of a recent initiative by the Faculty of Law at Hong Kong University (HKU). -

English Version

Indoor Air Quality Certificate Award Ceremony COS Centre 38/F and 39/F Offices (CIC Headquarters) Millennium City 6 Common Areas Wai Ming Block, Caritas Medical Centre Offices and Public Areas of Whole Building Premises Awarded with “Excellent Class” Certificate (Whole Building) COSCO Tower, Grand Millennium Plaza Public Areas of Whole Building Mira Place Tower A Public Areas of Whole Office Building Wharf T&T Centre 11/F Office (BOC Group Life Assurance Millennium City 5 BEA Tower D • PARK Baby Care Room and Feeding Room on Level 1 Mount One 3/F Function Room and 5/F Clubhouse Company Limited) Modern Terminals Limited - Administration Devon House Public Areas of Whole Building MTR Hung Hom Building Public Areas on G/F and 1/F Wharf T&T Centre Public Areas from 5/F to 17/F Building Dorset House Public Areas of Whole Building Nan Fung Tower Room 1201-1207 (Mandatory Provident Fund Wheelock House Office Floors from 3/F to 24/F Noble Hill Club House EcoPark Administration Building Offices, Reception, Visitor Centre and Seminar Schemes Authority) Wireless Centre Public Areas of Whole Building One Citygate Room Nina Tower Office Areas from 15/F to 38/F World Commerce Centre in Harbour City Public Areas from 5/F to 10/F One Exchange Square Edinburgh Tower Whole Office Building Ocean Centre in Harbour City Public Areas from 5/F to 17/F World Commerce Centre in Harbour City Public Areas from 11/F to 17/F One International Finance Centre Electric Centre 9/F Office Ocean Walk Baby Care Room World Finance Centre - North Tower in Harbour City Public Areas from 5/F to 17/F Sai Kung Outdoor Recreation Centre - Electric Tower Areas Equipped with MVAC System of The Office Tower, Convention Plaza 11/F & 36/F to 39/F (HKTDC) World Finance Centre - South Tower in Harbour City Public Areas from 5/F to 17/F Games Hall Whole Building Olympic House Public Areas of 1/F and 2/F World Tech Centre 16/F (Hong Yip Service Co. -

For Discussion on 15 March 2021 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL PANEL

LC Paper No. CB(4)605/20-21(04) For discussion on 15 March 2021 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL PANEL ON PUBLIC SERVICE Participation of Civil Servants in the Fight against COVID-19 Pandemic PURPOSE This paper briefs Members on the participation and concerted effort of civil servants in the fight against Coronavirus Disease - 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. BACKGROUND 2. The COVID-19 epidemic is wreaking havoc around the world and has brought unprecedented impacts both locally and internationally. On 25 January 2020, the Government raised the COVID-19 response level to Emergency Response Level. Under the direction of the Steering Committee cum Command Centre chaired by the Chief Executive, the Government has taken prompt and effective action in safeguarding public health by preventing the importation of cases on one hand and preventing the spreading of the virus in the community on the other. The Government has deployed stringent border control measures with a view to stopping the transmission of the virus at source. Strict enforcement of quarantine arrangements and closed-loop management for persons arriving in Hong Kong are in place for the prevention of imported cases. At the same time, the Government has been stepping up surveillance and testing efforts, enhancing contact tracing and implementing social distancing measures to prevent the spread of the virus in the community. All the anti-epidemic measures, programmes and operations could not be launched successfully without the many proactive effort that the civil service has made and the many extra miles that the civil service has walked. With the commitment to serving the community, the civil service stands unitedly to tackle the challenges brought by the epidemic despite all the difficulties encountered. -

Coaching Day-Hong Kong

Coaching Day-Hong Kong Food from Finland 4.5.2020 PROGRAM FOR THE DAY 9:00-9:10 AM Food from Finland 2020 plan for Hong Kong market 9:10-9:30 AM Hong Kong market overview 9:30-10:00 AM Profiling Future consumer in Hong Kong 10:00-10:15 AM Q&A 10:15-10:35 AM Finnish food and beverage export update 10:35-10:45 AM Coffee Break 10:45-11:45 AM Hong Kong import Food and beverage market analysis-PART 1 11:45-12:15 AM Lunch break 12:15-12:45 AM Hong Kong import Food and Beverage market analysis-PART 2 12:45-13:00 PM Q&A 13:00-13:20 PM Local support for Finnish food and beverage companies 13:20-14:00 PM Panel discussion with importers and speakers/ Q&A to all speakers Food from Finland Program . Food from Finland is team Finland’s Export Program for the Finland’s Food Sector since 2014. It’s funded by the Ministry of Economy and Employment and Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. We have a close collaboration with the Foreign Ministry of Affairs . The program is managed by Business Finland in cooperation with Team Finland operators, Finnish Food Authority and The Finnish Food and Drink Industries’ Federation (ETL) . The program’s goal is to increase the Finnish F&B export, open new markets, and to create new jobs . Focus market for export activities: Germany, China and Hong Kong SAR, Japan, South Korea, Sweden, Denmark, France, and Russia Program Activity in Hong Kong 2020 Training Day 4.5.2020 (Webinar) Coaching day-Hong Kong Other events in planning for Hong Kong market Date until further Vegetarian food Asia Expo notice 10.6.2020 Export via -

Panel on Administration of Justice and Legal Services

For discussion on 23 October 2017 Legislative Council Panel on Administration of Justice and Legal Services The Chief Executive’s 2017 Policy Address Policy Initiatives of the Home Affairs Bureau INTRODUCTION This paper briefs Members on the policy initiatives in respect of legal aid and free legal advice services in the Chief Executive’s 2017 Policy Address (“Policy Address”) and Policy Agenda. OUR VISION 2. Legal aid services form an integral part of the legal system in Hong Kong. We strive to ensure the accessibility of legal aid and free legal advice services to the public to contribute towards upholding the value of everyone being equal before the law. NEW INITIATIVES Transfer of the Legal Aid Portfolio 3. As announced in the Policy Address, following the recommendations of the Legal Aid Services Council (“LASC”) and taking into account views from stakeholders, the Chief Executive has decided to transfer the responsibilities for formulating legal aid policy and housekeeping the Legal Aid Department (“LAD”) from the Home Affairs Bureau (“HAB”) to the Chief Secretary for Administration’s Office. The transfer will take effect after the necessary approval has been obtained from the Legislative Council (“LegCo”). Review of Duty Lawyer Fees 4. The Government has decided to conduct a review of duty lawyer fees and will set up a working group for the purpose. We have invited the two legal professional bodies, the Duty Lawyer Service (“DLS”) and relevant government departments, namely the Department of Justice and LAD, to join the working group. Upon completion of the review, the Government will report the outcome to this Panel. -

247/20-21(01)號文件 LC Paper No. CB(2)247/20-21(01)

立法會CB(2)247/20-21(01)號文件 LC Paper No. CB(2)247/20-21(01) Submissions to the Legislative Council Panel on Constitutional Affairs’ Meeting on 16 November 2020 Agenda item IV Hearing of the United Nations Human Rights Committee on the Fourth Report of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region in the light of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1. Introduction Justice Centre Hong Kong appreciates this opportunity to provide comments on the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (“Hong Kong”)’s fourth review under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (“ICCPR”). In May 2020, Justice Centre submitted a civil society report to the United Nations Human Rights Committee with a focus on the ICCPR’s application in the migration context1. Justice Centre’s report details our concerns with the Unified Screening Mechanism, the Government’s asylum policy, immigration detention and the lack of protection for victims of human trafficking in all its forms. In August 2020 the Human Rights Committee released a List of Issues (“LoI”), in which most of the issues raised in Justice Centre’s report were adopted: see paragraphs 12 - 162. We reproduce our report to the Human Rights Committee below with updated statistics and other relevant developments since May 2020. We hope this information will assist the Hong Kong Government in preparing concrete answers to the Human Rights Committee’s List of Issues and engaging constructively in the review process. 2. Developments in Hong Kong’s protection landscape since 2013 There have been significant policy and legal changes in Hong Kong’s protection landscape since the Human Rights Committee last reviewed Hong Kong in 2013. -

Hong Kong Dollar (HK$) Which Is Accepted As Currency in Macau

Interesting & Fun Facts About Macau . The official name of Macau is Macau Special Administrative Region. The official languages of Macau are Portuguese and Chinese. Macau lies on the western side of the Pearl River Delta, bordering Guangdong province in the north. Majority of the people living in Macau are Buddhists, while one can also find Roman Catholics and Protestants here. The economy of Macau largely depends upon the revenue generated by tourism. Gambling is also a money-generating affair in the region. The currency of Macau is Macanese Pataca. After Las Vegas, Macau is one of the biggest gambling areas in the world. In fact, gambling is even legalized in Macau. Macau is the Special Administrative Region of China. It is one of the richest cities in the world. Colonized by the Portuguese in the 16th century, Macau was the first European settlement in the Far East. Macau is one of the most densely populated regions in the world. Macau ranks amongst the top 10 regions in the world, with a quite high life expectancy at birth. Macau is a highly humid region, with the humidity ranging anywhere between 75% and 90%. It receives fairly heavy rainfall as well. The Historic Centre of Macau, including twenty-five historic monuments and public squares, is listed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. The tourists of Macau should know that tipping is a very popular as well as important tradition followed in the region. Nearly 10% of the bill is given as tip in most of the restaurants and hotels of Macau http://goway.com/blog/2010/06/25/interesting-fun-facts-about-macau/ Basic Information on Macao (east-asian-games2005.com) Updated: 2005-09-27 15:23 Geographical Location Macau is located in the Guangdong province,on western bank of the Pearl River Delta,at latitude 22o14‘ North,longitude 133 o35‘ East and connected to the Gongbei District by the Border Gate (Portas do Cerco) isthmus.