Composition and the Music of Soundgarden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson

The Interplay of Authority, Masculinity, and Signification in the “Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Holly Johnson ii Abstract This thesis will deconstruct the "grunge killed '80s metal” narrative, to reveal the idealization by certain critics and musicians of that which is deemed to be authentic, honest, and natural subculture. The central theme is an analysis of the conflicting masculinities of glam metal and grunge music, and how these gender roles are developed and reproduced. I will also demonstrate how, although the idealized authentic subculture is positioned in opposition to the mainstream, it does not in actuality exist outside of the system of commercialism. The problematic nature of this idealization will be examined with regard to the layers of complexity involved in popular rock music genre evolution, involving the inevitable progression from a subculture to the mainstream that occurred with both glam metal and grunge. I will illustrate the ways in which the process of signification functions within rock music to construct masculinities and within subcultures to negotiate authenticity. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my academic advisor Dr. William Echard for his continued patience with me during the thesis writing process and for his invaluable guidance. I also would like to send a big thank you to Dr. James Deaville, the head of Music and Culture program, who has given me much assistance along the way. -

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

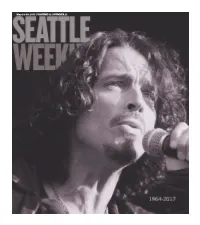

VOLUME 42 | NUMBER 21 Hen Chris Cornell Entered He Shrugged

May 24-30, 2017 | VOLUME 42 | NUMBER 21 hen Chris Cornell entered He shrugged. He spoke in short bursts of at a room, the air seemed to syllables. Soundgarden was split at the time, hum with his presence. All and he showed no interest in getting the eyes darted to him, then band back together. He showed little interest danced over his mop of in many of my questions. Until I noted he curls and lanky frame. He appeared to carry had a pattern of daring creative expression himself carelessly, but there was calculation outside of Soundgarden: Audioslave’s softer in his approach—the high, loose black side; bluesy solo eorts; the guitar-eschew- boots, tight jeans, and impeccable facial hair ing Scream with beatmaker Timbaland. his standard uniform. He was a rock star. At this, Cornell’s eyes sharpened. He He knew it. He knew you knew it. And that sprung forward and became fully engaged. didn’t make him any less likable. When he He got up and brought me an unsolicited left the stage—and, in my case, his Four bottled water, then paced a bit, talking all Seasons suite following a 2009 interview— the while. About needing to stay unpre- that hum leisurely faded, like dazzling dictable. About always trying new things. sunspots in the eyes. He told me that he wrote many songs “in at presence helped Cornell reach the character,” outside of himself. He said, “I’m pinnacle of popular music as front man for not trying to nd my musical identity, be- Soundgarden. -

SOUNDGARDEN Superunknown (Hard Rock)

SOUNDGARDEN Superunknown (Hard Rock) Année de sortie : 1994 Nombre de pistes : 16 Durée : 70' Support : CD Provenance : Acheté Nous avons décidé de vous faire découvrir (ou re découvrir) les albums qui ont marqué une époque et qui nous paraissent importants pour comprendre l'évolution de notre style préféré. Nous traiterons de l'album en le réintégrant dans son contexte originel (anecdotes, etc.)... Une chronique qui se veut 100% "passionnée" et "nostalgique" et qui nous l'espérons, vous fera réagir par le biais des commentaires ! ...... Bon voyage ! Formé à Seattle, SOUNDGARDEN est généralement associé à la mouvance Grunge qui explose en 1991 avec NIRVANA et son album essentiel Nevermind. La musique du groupe emmené par le chanteur Chris CORNELL ne se résume toutefois pas à ce courant. Des similitudes peuvent être constatées, en premier lieu de par l’appartenance des deux formations à cette nouvelle scène de Seattle. Bruce PAVITT, fondateur du label Sub Pop, figure en effet parmi les amis du groupe, ce qui lui permet, avant NIRVANA, de devenir la première formation signée par l’incontournable officine Underground. Ensuite, la musique de SOUNDGARDEN est fréquemment caractérisée par la noirceur et la mélancolie. Cependant, Badmotorfinger, deuxième effort du groupe publié en 1991 par la compagnie nationale A & M, avec laquelle il vient de conclure un contrat avantageux, révèle des influences qui le rattachent davantage au Metal. L’album comporte de nombreuses compositions reposant sur des riffs plombés. Ainsi Jesus Christ Pose rappelle fortement LED ZEPPELIN, et le groupe paie sa dette à BLACK SABBATH sur le titre Slaves & Bulldozers. Après ce disque acclamé par la critique, SOUNDGARDEN connaîtra son apogée avec la sortie en 1994 de Superunknown, qui devient numéro un aux États-Unis avec trois millions d’exemplaires vendus. -

Nudedragons to King Animal — the First Ever Fan-Based Compilation Photobook — Is Now Available!

PHOTOFANTASM SOUNDGARDEN: NUDEDRAGONS TO KING ANIMAL — THE FIRST EVER FAN-BASED COMPILATION PHOTOBOOK — IS NOW AVAILABLE! The only book ever created by the fans for any high-profile band, Photofantasm Soundgarden is dedicated to rock pioneers Soundgarden. It features commentary and recollections from fellow artists, the music press, and other notable contributors. SEATTLE, May 18, 2015 /PRNewswire/ Photofantasm Soundgarden: Nudedragons to King Animal highlights the Seattle band’s rebirth via hundreds of pages’ worth of photographs, graphic art, anecdotes, interviews, and reviews. In a truly collaborative effort, fans, artists, musicians, authors, photographers, and other notable personalities all help chronicle Soundgarden's performances across the globe from 2010 to 2013. To quote Everybody Loves Our Town: An Oral History of Grunge author Mark Yarm in his foreword to Photofantasm Soundgarden, the book is “by the fans, for the fans”—the book boasts more than 300 contributors from more than 30 countries on six continents—and captures what promises to be just the beginning of a very long second chapter! Much like classic vinyl, Photofantasm Soundgarden is a quality, limited-edition collector's item (only 1,000 copies) meant to be savored by the fans (and the band itself) for years to come. The heart of this book is a section devoted to the loving memory of an extraordinary friend and Soundgarden fan who courageously fought cancer. All net proceeds will go to Canary Foundation, the first and only foundation in the world solely dedicated to the funding of early cancer-detection solutions. Photofantasm totals 592 pages, much of it exclusive content. -

Grunge Is Dead Is an Oral History in the Tradition of Please Kill Me, the Seminal History of Punk

THE ORAL SEATTLE ROCK MUSIC HISTORY OF GREG PRATO WEAVING TOGETHER THE DEFINITIVE STORY OF THE SEATTLE MUSIC SCENE IN THE WORDS OF THE PEOPLE WHO WERE THERE, GRUNGE IS DEAD IS AN ORAL HISTORY IN THE TRADITION OF PLEASE KILL ME, THE SEMINAL HISTORY OF PUNK. WITH THE INSIGHT OF MORE THAN 130 OF GRUNGE’S BIGGEST NAMES, GREG PRATO PRESENTS THE ULTIMATE INSIDER’S GUIDE TO A SOUND THAT CHANGED MUSIC FOREVER. THE GRUNGE MOVEMENT MAY HAVE THRIVED FOR ONLY A FEW YEARS, BUT IT SPAWNED SOME OF THE GREATEST ROCK BANDS OF ALL TIME: PEARL JAM, NIRVANA, ALICE IN CHAINS, AND SOUNDGARDEN. GRUNGE IS DEAD FEATURES THE FIRST-EVER INTERVIEW IN WHICH PEARL JAM’S EDDIE VEDDER WAS WILLING TO DISCUSS THE GROUP’S HISTORY IN GREAT DETAIL; ALICE IN CHAINS’ BAND MEMBERS AND LAYNE STALEY’S MOM ON STALEY’S DRUG ADDICTION AND DEATH; INSIGHTS INTO THE RIOT GRRRL MOVEMENT AND OFT-OVERLOOKED BUT HIGHLY INFLUENTIAL SEATTLE BANDS LIKE MOTHER LOVE BONE, THE MELVINS, SCREAMING TREES, AND MUDHONEY; AND MUCH MORE. GRUNGE IS DEAD DIGS DEEP, STARTING IN THE EARLY ’60S, TO EXPLAIN THE CHAIN OF EVENTS THAT GAVE WAY TO THE MUSIC. THE END RESULT IS A BOOK THAT INCLUDES A WEALTH OF PREVIOUSLY UNTOLD STORIES AND FRESH INSIGHT FOR THE LONGTIME FAN, AS WELL AS THE ESSENTIALS AND HIGHLIGHTS FOR THE NEWCOMER — THE WHOLE UNCENSORED TRUTH — IN ONE COMPREHENSIVE VOLUME. GREG PRATO IS A LONG ISLAND, NEW YORK-BASED WRITER, WHO REGULARLY WRITES FOR ALL MUSIC GUIDE, BILLBOARD.COM, ROLLING STONE.COM, RECORD COLLECTOR MAGAZINE, AND CLASSIC ROCK MAGAZINE. -

![D841o [Free Download] Love Death: the Murder of Kurt Cobain Online](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4019/d841o-free-download-love-death-the-murder-of-kurt-cobain-online-144019.webp)

D841o [Free Download] Love Death: the Murder of Kurt Cobain Online

d841o [Free download] Love Death: The Murder of Kurt Cobain Online [d841o.ebook] Love Death: The Murder of Kurt Cobain Pdf Free Par Max Wallace, Ian Halperin ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook Détails sur le produit Rang parmi les ventes : #289088 dans eBooksPublié le: 2014-03-20Sorti le: 2014-03- 20Format: Ebook Kindle | File size: 26.Mb Par Max Wallace, Ian Halperin : Love Death: The Murder of Kurt Cobain before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Love Death: The Murder of Kurt Cobain: Commentaires clientsCommentaires clients les plus utiles0 internautes sur 0 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. A couper le soufflePar TichatDu vrai journalisme investigatif. Bien écrit, très bien recherché, objectif, avec des révélations inattendues et hallucinantes.Se lit tel qu'un thriller à en oublier presque qu'il s'agit malheureusement de faits réels.0 internautes sur 0 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. GREAT SELLER +++ FAST, CLEAN,PERFECT ... WHAT ELSE ?Par guichardGREAT SELLER +++ FAST, CLEAN,PERFECT ... WHAT ELSE ?GREAT SELLER +++ FAST, CLEAN,PERFECT ... WHAT ELSE ?GREAT SELLER +++ FAST, CLEAN,PERFECT ... WHAT ELSE ? Présentation de l'éditeurTHE EXPLOSIVE INVESTIGATION INTO THE DEATH OF KURT COBAIN. Friday, 8th April 1994. Kurt Cobain's body was discovered in a room above a garage in Seattle. For the attending authorities, it was an open-and-shut case of suicide. What no one knew was Cobain had been murdered. That April, Cobain went missing for several days, or so it seemed: in fact, some people knew where he was, and one of them was Courtney Love. -

A Case Study of Kurt Donald Cobain

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by South East Academic Libraries System (SEALS) A CASE STUDY OF KURT DONALD COBAIN By Candice Belinda Pieterse Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Magister Artium in Counselling Psychology in the Faculty of Health Sciences at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University December 2009 Supervisor: Prof. J.G. Howcroft Co-Supervisor: Dr. L. Stroud i DECLARATION BY THE STUDENT I, Candice Belinda Pieterse, Student Number 204009308, for the qualification Magister Artium in Counselling Psychology, hereby declares that: In accordance with the Rule G4.6.3, the above-mentioned treatise is my own work and has not previously been submitted for assessment to another University or for another qualification. Signature: …………………………………. Date: …………………………………. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are several individuals that I would like to acknowledge and thank for all their support, encouragement and guidance whilst completing the study: Professor Howcroft and Doctor Stroud, as supervisors of the study, for all their help, guidance and support. As I was in Bloemfontein, they were still available to meet all my needs and concerns, and contribute to the quality of the study. My parents and Michelle Wilmot for all their support, encouragement and financial help, allowing me to further my academic career and allowing me to meet all my needs regarding the completion of the study. The participants and friends who were willing to take time out of their schedules and contribute to the nature of this study. Konesh Pillay, my friend and colleague, for her continuous support and liaison regarding the completion of this study. -

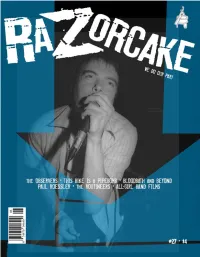

Read Razorcake Issue #27 As A

t’s never been easy. On average, I put sixty to seventy hours a Yesterday, some of us had helped our friend Chris move, and before we week into Razorcake. Basically, our crew does something that’s moved his stereo, we played the Rhythm Chicken’s new 7”. In the paus- IInot supposed to happen. Our budget is tiny. We operate out of a es between furious Chicken overtures, a guy yelled, “Hooray!” We had small apartment with half of the front room and a bedroom converted adopted our battle call. into a full-time office. We all work our asses off. In the past ten years, That evening, a couple bottles of whiskey later, after great sets by I’ve learned how to fix computers, how to set up networks, how to trou- Giant Haystacks and the Abi Yoyos, after one of our crew projectile bleshoot software. Not because I want to, but because we don’t have the vomited with deft precision and another crewmember suffered a poten- money to hire anybody to do it for us. The stinky underbelly of DIY is tially broken collarbone, This Is My Fist! took to the six-inch stage at finding out that you’ve got to master mundane and difficult things when The Poison Apple in L.A. We yelled and danced so much that stiff peo- you least want to. ple with sourpusses on their faces slunk to the back. We incited under- Co-founder Sean Carswell and I went on a weeklong tour with our aged hipster dancing. -

The Musicares Foundation® 3402 Pico Boulevard, Santa Monica, CA 90405

The MusiCares Foundation® 3402 Pico Boulevard, Santa Monica, CA 90405 ***TIP SHEET FOR FRIDAY, MAY 9, 2008*** BLIND MELON AND CAMP FREDDY — WITH SPECIAL GUESTS CHESTER BENNINGTON, WAYNE KRAMER, DUFF MCKAGAN, CHAD SMITH, STEVEN TYLER AND ROBIN ZANDER — TO PERFORM AT FOURTH ANNUAL MUSICARES MAP FUNDSM BENEFIT CONCERT ON MAY 9 HONORING ALICE COOPER AND SLASH Sold-Out Concert Event — Sponsored In Part By Gibson Foundation — At The Music Box @ Fonda Will Raise Funds For MusiCares® Addiction Recovery Services WHO: Honorees: Legendary artist Alice Cooper to receive the Stevie Ray Vaughan Award and GRAMMY®-winning guitarist Slash to receive the MusiCares® From the Heart Award. Host: Actor, stand-up comedian, musician and singer Tommy Davidson. Presenters: Bernie Taupin will present the Stevie Ray Vaughan Award to honoree Alice Cooper; Steven Tyler will present the MusiCares® From the Heart Award to honoree Slash. Performers: Blind Melon (Glen Graham, Brad Smith, Rogers Stevens, Christopher Thorn and Travis Warren) and Camp Freddy (Chris Chaney, Donovan Leitch, Billy Morrison and Matt Sorum) with Slash on guitar, along with special guests Chester Bennington (Linkin Park), Wayne Kramer (MC5), Duff McKagan (Velvet Revolver), Chad Smith (Red Hot Chili Peppers), Steven Tyler (Aerosmith) and Robin Zander (Cheap Trick). The evening will also feature special performances by Alice Cooper and Slash. Attendees: MusiCares Foundation Board Chair John Branca; Gilby Clarke (Guns N' Roses); Bob Forrest (Celebrity Rehab); Anthony Kiedis (Red Hot Chili Peppers); Dave Kushner (Velvet Revolver); Martyn LeNoble (Jane's Addiction and Porno For Pyros); and President/CEO of The Recording Academy® and President of the MusiCares Foundation Neil Portnow. -

Soundgarden Singer Chris Cornell Dies at Age 52 in Detroit

Transforming Former FBI Real Madrid old newspapers director to lead within point into something Russia probe of Liga title beautiful4 15 46 Min 27º Max 44º FREE www.kuwaittimes.net NO: 17232- Friday, May 19, 2017 70th Cannes Film CANNES: Thai actress Araya Alberta Hargate known as Chompoo poses as she arrives on May 17, 2017 for the screening of the film ‘Ismael’s Festival kicks off Ghosts’ (Les Fantomes d’Ismael) during the opening ceremony of the 70th edition of the Cannes Page 22 Film Festival. — AFP Local FRIDAY, MAY 19, 2017 Local Spotlight Photo of the day Flying gravel By Muna Al-Fuzai [email protected] he court of appeal rejected a claim by a Twoman for KD 5,000 in compensation for damage to her vehicle as a result of flying gravel on the roads. The rejection of the case sent a message to everyone not to trouble themselves to file more cases and hire lawyers, because those who are affected due to the bad job by the con- tractor and the ministry of public works need to remain silent and accept the reality. Or take the long road of insurance companies and garages to repair the damage and pay for it. For more than a year now, many people have been suffering from the flying stones on the roads that is damaging their cars, especially when the windshield shatters, forcing motorists to pay from their own pockets to change the glass and repair the cars, whether tires or other parts. These complaints led many people to sue the govern- ment for damages, but it is no surprise that the case was denied. -

Charles Peterson …And Everett True Is 481

Dwarves Photos: Charles Peterson …and Everett True is 481. 19 years on from his first Seattle jolly on the Sub Pop account, Plan B’s publisher-at-large jets back to the Pacific Northwest to meet some old friends, exorcise some ghosts and find out what happened after grunge left town. How did we get here? Where are we going? And did the Postal Service really sell that many records? Words: Everett True Transcripts: Natalie Walker “Heavy metal is objectionable. I don’t even know comedy genius, the funniest man I’ve encountered like, ‘I have no idea what you’re doing’. But he where that [comparison] comes from. People will in the Puget Sound8. He cracks me up. No one found trusted the four of us enough to let us go into the say that Motörhead is a metal band and I totally me attractive until I changed my name. The name studio for a weekend and record with Jack. It was disagree, and I disagree that AC/DC is a metal band. slides into meaninglessness. What is the Everett True essentially a demo that became our first single.” To me, those are rock bands. There’s a lot of Chuck brand in 2008? What does Sub Pop stand for, more Berry in Motörhead. It’s really loud and distorted and than 20 years after its inception? Could Sub Pop It’s in the focus. The first time I encountered Sub amplified but it’s there – especially in the earlier have existed without Everett True? Could Everett Pop, I had 24 hours to write up my first cover feature stuff.