Cor 2017 0214 Finding Into Death

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub

US 20130289061A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2013/0289061 A1 Bhide et al. (43) Pub. Date: Oct. 31, 2013 (54) METHODS AND COMPOSITIONS TO Publication Classi?cation PREVENT ADDICTION (51) Int. Cl. (71) Applicant: The General Hospital Corporation, A61K 31/485 (2006-01) Boston’ MA (Us) A61K 31/4458 (2006.01) (52) U.S. Cl. (72) Inventors: Pradeep G. Bhide; Peabody, MA (US); CPC """"" " A61K31/485 (201301); ‘4161223011? Jmm‘“ Zhu’ Ansm’ MA. (Us); USPC ......... .. 514/282; 514/317; 514/654; 514/618; Thomas J. Spencer; Carhsle; MA (US); 514/279 Joseph Biederman; Brookline; MA (Us) (57) ABSTRACT Disclosed herein is a method of reducing or preventing the development of aversion to a CNS stimulant in a subject (21) App1_ NO_; 13/924,815 comprising; administering a therapeutic amount of the neu rological stimulant and administering an antagonist of the kappa opioid receptor; to thereby reduce or prevent the devel - . opment of aversion to the CNS stimulant in the subject. Also (22) Flled' Jun‘ 24’ 2013 disclosed is a method of reducing or preventing the develop ment of addiction to a CNS stimulant in a subj ect; comprising; _ _ administering the CNS stimulant and administering a mu Related U‘s‘ Apphcatlon Data opioid receptor antagonist to thereby reduce or prevent the (63) Continuation of application NO 13/389,959, ?led on development of addiction to the CNS stimulant in the subject. Apt 27’ 2012’ ?led as application NO_ PCT/US2010/ Also disclosed are pharmaceutical compositions comprising 045486 on Aug' 13 2010' a central nervous system stimulant and an opioid receptor ’ antagonist. -

Recommended Methods for the Identification and Analysis Of

Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: (+43-1) 26060-0, Fax: (+43-1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org RECOMMENDED METHODS FOR THE IDENTIFICATION AND ANALYSIS OF AMPHETAMINE, METHAMPHETAMINE AND THEIR RING-SUBSTITUTED ANALOGUES IN SEIZED MATERIALS (revised and updated) MANUAL FOR USE BY NATIONAL DRUG TESTING LABORATORIES Laboratory and Scientific Section United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Vienna RECOMMENDED METHODS FOR THE IDENTIFICATION AND ANALYSIS OF AMPHETAMINE, METHAMPHETAMINE AND THEIR RING-SUBSTITUTED ANALOGUES IN SEIZED MATERIALS (revised and updated) MANUAL FOR USE BY NATIONAL DRUG TESTING LABORATORIES UNITED NATIONS New York, 2006 Note Mention of company names and commercial products does not imply the endorse- ment of the United Nations. This publication has not been formally edited. ST/NAR/34 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. E.06.XI.1 ISBN 92-1-148208-9 Acknowledgements UNODC’s Laboratory and Scientific Section wishes to express its thanks to the experts who participated in the Consultative Meeting on “The Review of Methods for the Identification and Analysis of Amphetamine-type Stimulants (ATS) and Their Ring-substituted Analogues in Seized Material” for their contribution to the contents of this manual. Ms. Rosa Alis Rodríguez, Laboratorio de Drogas y Sanidad de Baleares, Palma de Mallorca, Spain Dr. Hans Bergkvist, SKL—National Laboratory of Forensic Science, Linköping, Sweden Ms. Warank Boonchuay, Division of Narcotics Analysis, Department of Medical Sciences, Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi, Thailand Dr. Rainer Dahlenburg, Bundeskriminalamt/KT34, Wiesbaden, Germany Mr. Adrian V. Kemmenoe, The Forensic Science Service, Birmingham Laboratory, Birmingham, United Kingdom Dr. Tohru Kishi, National Research Institute of Police Science, Chiba, Japan Dr. -

Drugs of Abuseon September Archived 13-10048 No

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE DRUG ENFORCEMENT ADMINISTRATION WWW.DEA.GOV 9, 2014 on September archived 13-10048 No. v. Stewart, in U.S. cited Drugs of2011 Abuse EDITION A DEA RESOURCE GUIDE V. Narcotics WHAT ARE NARCOTICS? Also known as “opioids,” the term "narcotic" comes from the Greek word for “stupor” and originally referred to a variety of substances that dulled the senses and relieved pain. Though some people still refer to all drugs as “narcot- ics,” today “narcotic” refers to opium, opium derivatives, and their semi-synthetic substitutes. A more current term for these drugs, with less uncertainty regarding its meaning, is “opioid.” Examples include the illicit drug heroin and pharmaceutical drugs like OxyContin®, Vicodin®, codeine, morphine, methadone and fentanyl. WHAT IS THEIR ORIGIN? The poppy papaver somniferum is the source for all natural opioids, whereas synthetic opioids are made entirely in a lab and include meperidine, fentanyl, and methadone. Semi-synthetic opioids are synthesized from naturally occurring opium products, such as morphine and codeine, and include heroin, oxycodone, hydrocodone, and hydromorphone. Teens can obtain narcotics from friends, family members, medicine cabinets, pharmacies, nursing 2014 homes, hospitals, hospices, doctors, and the Internet. 9, on September archived 13-10048 No. v. Stewart, in U.S. cited What are common street names? Street names for various narcotics/opioids include: ➔ Hillbilly Heroin, Lean or Purple Drank, OC, Ox, Oxy, Oxycotton, Sippin Syrup What are their forms? Narcotics/opioids come in various forms including: ➔ T ablets, capsules, skin patches, powder, chunks in varying colors (from white to shades of brown and black), liquid form for oral use and injection, syrups, suppositories, lollipops How are they abused? ➔ Narcotics/opioids can be swallowed, smoked, sniffed, or injected. -

Introduced B.,Byhansen, 16

LB301 LB301 2021 2021 LEGISLATURE OF NEBRASKA ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH LEGISLATURE FIRST SESSION LEGISLATIVE BILL 301 Introduced by Hansen, B., 16. Read first time January 12, 2021 Committee: Judiciary 1 A BILL FOR AN ACT relating to the Uniform Controlled Substances Act; to 2 amend sections 28-401, 28-405, and 28-416, Revised Statutes 3 Cumulative Supplement, 2020; to redefine terms; to change drug 4 schedules and adopt federal drug provisions; to change a penalty 5 provision; and to repeal the original sections. 6 Be it enacted by the people of the State of Nebraska, -1- LB301 LB301 2021 2021 1 Section 1. Section 28-401, Revised Statutes Cumulative Supplement, 2 2020, is amended to read: 3 28-401 As used in the Uniform Controlled Substances Act, unless the 4 context otherwise requires: 5 (1) Administer means to directly apply a controlled substance by 6 injection, inhalation, ingestion, or any other means to the body of a 7 patient or research subject; 8 (2) Agent means an authorized person who acts on behalf of or at the 9 direction of another person but does not include a common or contract 10 carrier, public warehouse keeper, or employee of a carrier or warehouse 11 keeper; 12 (3) Administration means the Drug Enforcement Administration of the 13 United States Department of Justice; 14 (4) Controlled substance means a drug, biological, substance, or 15 immediate precursor in Schedules I through V of section 28-405. 16 Controlled substance does not include distilled spirits, wine, malt 17 beverages, tobacco, hemp, or any nonnarcotic substance if such substance 18 may, under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, 21 U.S.C. -

Application of High Resolution Mass Spectrometry for the Screening and Confirmation of Novel Psychoactive Substances Joshua Zolton Seither [email protected]

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 4-25-2018 Application of High Resolution Mass Spectrometry for the Screening and Confirmation of Novel Psychoactive Substances Joshua Zolton Seither [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC006565 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Chemistry Commons Recommended Citation Seither, Joshua Zolton, "Application of High Resolution Mass Spectrometry for the Screening and Confirmation of Novel Psychoactive Substances" (2018). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3823. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3823 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida APPLICATION OF HIGH RESOLUTION MASS SPECTROMETRY FOR THE SCREENING AND CONFIRMATION OF NOVEL PSYCHOACTIVE SUBSTANCES A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in CHEMISTRY by Joshua Zolton Seither 2018 To: Dean Michael R. Heithaus College of Arts, Sciences and Education This dissertation, written by Joshua Zolton Seither, and entitled Application of High- Resolution Mass Spectrometry for the Screening and Confirmation of Novel Psychoactive Substances, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Piero Gardinali _______________________________________ Bruce McCord _______________________________________ DeEtta Mills _______________________________________ Stanislaw Wnuk _______________________________________ Anthony DeCaprio, Major Professor Date of Defense: April 25, 2018 The dissertation of Joshua Zolton Seither is approved. -

Model Scheduling New/Novel Psychoactive Substances Act (Third Edition)

Model Scheduling New/Novel Psychoactive Substances Act (Third Edition) July 1, 2019. This project was supported by Grant No. G1799ONDCP03A, awarded by the Office of National Drug Control Policy. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the Office of National Drug Control Policy or the United States Government. © 2019 NATIONAL ALLIANCE FOR MODEL STATE DRUG LAWS. This document may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes with full attribution to the National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws. Please contact NAMSDL at [email protected] or (703) 229-4954 with any questions about the Model Language. This document is intended for educational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice or opinion. Headquarters Office: NATIONAL ALLIANCE FOR MODEL STATE DRUG 1 LAWS, 1335 North Front Street, First Floor, Harrisburg, PA, 17102-2629. Model Scheduling New/Novel Psychoactive Substances Act (Third Edition)1 Table of Contents 3 Policy Statement and Background 5 Highlights 6 Section I – Short Title 6 Section II – Purpose 6 Section III – Synthetic Cannabinoids 13 Section IV – Substituted Cathinones 19 Section V – Substituted Phenethylamines 23 Section VI – N-benzyl Phenethylamine Compounds 25 Section VII – Substituted Tryptamines 28 Section VIII – Substituted Phenylcyclohexylamines 30 Section IX – Fentanyl Derivatives 39 Section X – Unclassified NPS 43 Appendix 1 Second edition published in September 2018; first edition published in 2014. Content in red bold first added in third edition. © 2019 NATIONAL ALLIANCE FOR MODEL STATE DRUG LAWS. This document may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes with full attribution to the National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws. -

Agenda Florida Hospital Association 307 Park Lake Circle Orlando, FL July 14, 2016 @ 2:00 P.M

The Florida Board of Nursing Controlled Substances Formulary Committee Agenda Florida Hospital Association 307 Park Lake Circle Orlando, FL July 14, 2016 @ 2:00 p.m. Doreen Cassarino, DNP, ARNP, FNP-BC, BC- ADM, FAANP - Chair Joe Baker, Jr. Executive Director Kathryn L Controlled Substances Formulary Committee Agenda July 14, 2016 @ 2:00 p.m. Committee Members: Doreen Cassarino, DNP, FNP-BC, BC-ADM, FAANP (Chair) Vicky Stone-Gale, DNP, FNP-C, MSN Jim Quinlan, DNP, ARNP Bernardo B. Fernandez, Jr., MD, MBA, FACP Joshua D. Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM Eduardo C. Oliveira, MD, MBA, FCCP Jeffrey Mesaros, PharmD, JD Attorney: Lee Ann Gustafson, Senior Assistant Attorney General Board Staff: Joe Baker, Jr., Executive Director Jessica Hollingsworth, Program Operations Administrator For more information regarding board meetings please visit http://floridasnursing.gov/meeting-information/ Or contact: Florida Board of Nursing 4052 Bald Cypress Way, Bin # C-02 Tallahassee, FL 32399-3252 Direct Line: (850)245-4125/Direct Fax: (850)617-6450 Email: [email protected] Call to Order Roll Call Committee Members: Doreen Cassarino, DNP, FNP-BC, BC-ADM, FAANP (Chair) Vicky Stone-Gale, DNP, FNP-C, MSN Jim Quinlan, DNP, ARNP Bernardo B. Fernandez, Jr., MD, MBA, FACP Joshua D. Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM Eduardo C. Oliveira, MD, MBA, FCCP Jeffrey Mesaros, PharmD, JD Attorney: Lee Ann Gustafson, Senior Assistant Attorney General Board Staff: Joe Baker, Jr., Executive Director Jessica Hollingsworth, Program Operations Administrator I. Review & Approve Minutes from June 29, 2016 Meeting II. Open Discussion A. Recommendations to the Board of Nursing for Rule Promulgation B. Reference Material 1. -

Analysis of N,N‐Dimethylamphetamine In

This item is the archived peer-reviewed author-version of: Analysis of N,N-dimethylamphetamine in wastewater : a pyrolysis marker and synthesis impurity of methamphetamine Reference: Been Frederic, O'Brien Jake, Lai Foon Yin, Morelato Marie, Vallely Peter, McGow an Jenny, van Nuijs Alexander, Covaci Adrian, Mueller Jochen F..- Analysis of N,N-dimethylamphetamine in w astew ater : a pyrolysis marker and synthesis impurity of methamphetamine Drug testing and analysis - ISSN 1942-7603 - 10:10(2018), p. 1590-1598 Full text (Publisher's DOI): https://doi.org/10.1002/DTA.2419 To cite this reference: https://hdl.handle.net/10067/1547480151162165141 Institutional repository IRUA Analysis of N,N-Dimethylamphetamine in Wastewater – A Pyrolysis Marker and Synthesis Impurity of Methamphetamine Frederic Been*1, Jake O’Brien2, Foon Yin Lai1, Marie Morelato3, Peter Vallely4, Jenny McGowan5, Alexander L. N. van Nuijs1, Adrian Covaci1, Jochen F. Mueller2 1Toxicological Centre, University of Antwerp, 2610 Antwerp, Belgium 2Queensland Alliance for Environmental Health Sciences, The University of Queensland, 4101 Coopers Plains, QLD, Australia. 3Centre for Forensic Science, University of Technology Sydney, PO Box 123, 2007 Broadway, NSW, Australia. 4Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission, 2601 Canberra, Australia 5Forensic and Scientific Services, Queensland Health, 4101 Coopers Plains, QLD, Australia *Corresponding author Email: [email protected] Phone: +32 3 265 27 43 This article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this article as doi: 10.1002/dta.2419 This article is protected by copyright. -

Amphetamine-Type Stimulants in Drug Testing

Vol. 10, No. 1, 2019 ISSN 2233-4203/ e-ISSN 2093-8950 REVIEW www.msletters.org | Mass Spectrometry Letters Amphetamine-type Stimulants in Drug Testing Heesun Chung1,* and Sanggil Choe2 1Graduate School of Analytical Science and Technology, Chungnam National University, Daejeon, Korea 2Forensic Toxicology Section, Seoul Institute, National Forensic Service, Seoul, Korea Received September 2, 2018; Revised December 18, 2018; Accepted December 18, 2018 First published on the web March 31, 2019; DOI: 10.5478/MSL.2019.10.1.1 Abstract : Amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS) are a group of β-phenethylamine derivatives that produce central nervous sys- tem stimulants effects. The representative ATS are methamphetamine and 3, 4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), and abuse of ATS has become a global problem. Methamphetamine is abused in North America and Asia, while amphetamine and 3, 4-methyl e nedioxy m ethamphetamine (Ecstasy) are abused in Europe and Australia. Methamphetamine is also the most abused drug in Korea. In addition to the conventional ATS, new psychoactive substances (NPS) including phenethylamines and synthetic cathinones, which have similar effects and chemical structure to ATS, continue to spread to the global market since 2009, and more than 739 NPS have been identified. For the analysis of ATS, two tests that have different theoretical principles have to be conducted, and screening tests by immunoassay and confirmatory tests using GC/MS or LC/MS are the global stan- dard methods. As most ATS have a chiral center, enantiomer separation is an important point in forensic analysis, and it can be conducted using chiral derivatization reagents or chiral columns. In order to respond to the growing drug crime, it is necessary to develop a fast and efficient analytical method. -

Model Scheduling New Novel Psychoactive Substances

Model Scheduling New/Novel Psychoactive Substances Act September 2018 (original version published in 2014). This project was supported by Grant No. G1799ONDCP03A, awarded by the Office of National Drug Control Policy. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the Office of National Drug Control Policy or the United States Government. © 2018. NATIONAL ALLIANCE FOR MODEL STATE DRUG LAWS. This document may be reproduced for non- commercial purposes with full attribution to the National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws. Please contact Jon Woodruff at [email protected] or (703) 836-7496 with any questions about the Model Language. This document is intended for educational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice or opinion. Headquarters Office: THE NATIONAL ALLIANCE 1 FOR MODEL STATE DRUG LAWS, 1335 North Front Street, First Floor, Harrisburg, PA, 17102-2629. Model Scheduling New/Novel Psychoactive Substances Act Table of Contents 3 Policy Statement and Background 5 Highlights 6 Section I – Short Title 6 Section II – Purpose 6 Section III – Synthetic Cannabinoids 12 Section IV – Substituted Cathinones 18 Section V – Substituted Phenethylamines 22 Section VI – N-benzyl Phenethylamine Compounds 24 Section VII – Substituted Tryptamines 27 Section VIII – Substituted Phenylcyclohexylamines 28 Section IX – Fentanyl Derivatives 37 Section X – Unclassified NPS © 2018. NATIONAL ALLIANCE FOR MODEL STATE DRUG LAWS. This document may be reproduced for non- commercial purposes with full attribution to the National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws. Please contact Jon Woodruff at [email protected] or (703) 836-7496 with any questions about the Model Language. -

Update on Clandestine Amphetamines and Their Analogues Recently Seen in Japan

14 Journal of Health Science, 48(1) 14–21 (2002) — Minireview — Update on Clandestine Amphetamines and Their Analogues Recently Seen in Japan Munehiro Katagi* and Hitoshi Tsuchihashi Forensic Science Laboratory, Osaka Prefectural Police H.Q., 1–3–18 Hommachi, Chuo-ku, Osaka 541–0053, Japan (Received October 12, 2001) Amphetamines and their analogues have undergone a cycle of popularity as recreational drugs in Japan. The current wave of popularity began in the early 1990s and spread throughout the country. More recently, not only 3,4- methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) but also other designer amphetamines analogues, including p- methoxyamphetamine (PMA), 2,5-dimethoxy-4-ethylthiophenethylamine (2C-T-2), etc., have been extensively and increasingly abused, mainly among juveniles. This minireview presents an update on the amphetamines and their analogues by focusing on clandestine tablets encountered in Japan recently. Key words —–— amphetamines, amphetamine analogue, clandestine tablet INTRODUCTION identification of amphetamines and their analogues have recently been reported.6–10) Drug abuse, which affects human nature and This minireview presents an update on amphet- causes numerous crimes, has become a serious prob- amines and their analogues which have been sub- lem throughout the world. d-Methamphetamine hy- mitted to our laboratory for forensic drug analysis drochloride (d-MA HCl) crystalline has been the primarily in tablet form. most extensively and increasingly used illicit drug in Japan, although l-MA HCl crystalline has also Amphetamines often been encountered in the last four autumn sea- In most cases, amphetamines contained in clan- sons.1–3) Additionally, d-dimethylamphetamine hy- destine tablets seized in Japan have been found to drochloride (d-DMA HCl) crystalline emerged in be MA. -

Substance: Metamfepramone Based on the Current

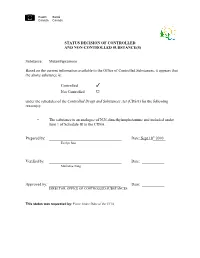

Health Santé Canada Canada STATUS DECISION OF CONTROLLED AND NON-CONTROLLED SUBSTANCE(S) Substance: Metamfepramone Based on the current information available to the Office of Controlled Substances, it appears that the above substance is: Controlled T Not Controlled 9 under the schedules of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA) for the following reason(s): • The substance is an analogue of N,N-dimethylamphetamine and included under item 1 of Schedule III to the CDSA. Prepared by: Date: Sept 10th 2010 Evelyn Soo Verified by: Date: Marianne Tang Approved by: Date: DIRECTOR, OFFICE OF CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES This status was requested by: Pierre Andre Dube of the CFIA Drug Status Report Drug: Metamfepramone Drug Name Status: Metamfepramone is the proper (INN) name. Chemical Name: 2-(Dimethylamino)-1-phenyl-1-propanone Other Names: Dimethylcathinone; dimethylpropion; dimepropion Chemical structure: Dimethylamphetamine (DMA) Molecular Formula: C11H15NO Pharmacological class / Application: Stimulant CAS-RN: 15351-09-4 International status: US: The substance is not listed specifically in the Controlled Substances Act and is not mentioned anywhere on the DEA website. United Nations: The substance is not listed on the Yellow List - List of Narcotic Drugs under International Control nor the Green List - List of Psychotropic Substances under International Control. Canadian Status: Metamfepramone is a sympathomimetic agent that is used for the treatment of the common cold and hyptonic conditions1. The substance is not currently listed in the CDSA but is considered to be an analogue of dimethylamphetamine; an analogue being a substance that displays significant structural similarity to one included in the CDSA for the purpose of forming status decisions.