How For-Profit Colleges Target Veterans and What the Government Must Do to Stop Them

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apollo Group, Inc

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 10-K (Mark One) ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended: August 31, 2004 or o TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission file number: 0-25232 Apollo Group, Inc. (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) Arizona 86-0419443 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 4615 EAST ELWOOD STREET, PHOENIX, ARIZONA 85040 (Address of principal executive offices, including zip code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (480) 966-5394 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: None None (Title of each class) (Name of each exchange on which registered) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: Apollo Education Group Class A common stock, no par value (Title of class) Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant: (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports); and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes No o Indicate by check mark if disclosure of delinquent filers pursuant to Item 405 of Regulation S-K is not contained herein, and will not be contained, to the best of Registrant’s knowledge, in definitive proxy or information statements incorporated by reference in Part III of this Form 10-K or any amendment to this Form 10-K. -

State Inaction: Gaps in State Oversight of For-Profit Higher

STATE INACTION GAPS IN STATE OVERSIGHT OF FOR-PROFIT HIGHER EDUCATION NCLC® NATIONAL CONSUMER December 2011 LAW CENTER® © Copyright 2011, National Consumer Law Center, Inc. All rights reserved. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Deanne Loonin is a staff attorney at the National Consumer Law Center (NCLC) and the Director of NCLC’s Student Loan Borrower Assistance Project. She was formerly a legal services attorney in Los Angeles. She is the author of numerous publications and reports, including NCLC publications Student Loan Law and Surviving Debt. Jillian McLaughlin is a research assistant at NCLC. She graduated from Kalamazoo College with a degree in political science. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report is a release of the National Consumer Law Center’s Student Loan Borrower Assis- tance Project [www.studentloanborrowerassistance.org]. The authors thank NCLC colleagues Carolyn Carter, Jan Kruse, and Persis Yu for valuable comments and assistance. We also thank Allen Agnitti, Laura Kirshner, and Kurt Terwilliger for research assistance. The findings and conclusions presented in this report are those of the authors alone. NCLC® ABOUT THE NATIONAL CONSUMER LAW CENTER The National Consumer Law Center®, a nonprofit corporation founded in 1969, assists NATIONAL consumers, advocates, and public policy makers nationwide on consumer law issues. CONSUMER NCLC works toward the goal of consumer justice and fair treatment, particularly for those whose poverty renders them powerless to demand accountability from the economic LAW marketplace. NCLC has provided model language and testimony on numerous consumer CENTER law issues before federal and state policy makers. NCLC publishes an 18-volume series ® of treatises on consumer law, and a number of publications for consumers. -

• Create a Faculty Guide, with Further Details, Explanation and Readings

On June 5, 2017, the Governor of Arizona declared a Public Health State of Emergency due to the Opioid Epidemic. More than two Arizonans were dying each day from an opioid overdose. Educational leaders from 18 Arizona undergraduate health educational programs (and registered nurse practitioner programs) gathered and agreed that a change in education must be made. Over the course of four meetings, best practices were shared and educational theories and national trends were reviewed. The group developed and systemically reviewed curriculum drafts for relevance and scope. The following foundations were established upon which to build a modern curriculum: • The link between pain and addiction • The flip to a macro-to-micro perspective on pain and addiction (a socio-psycho-biological model) • The influence of the pharmaceutical industry on clinicians 1 Define pain and addiction as multidimensional, public health problems. • The introspection of clinicians and systems, both in personal biases and excellence of care Describe the environmental, healthcare systems and care model factors that have shaped the 2 current opioid epidemic and approach to pain care. Describe the interrelated nature of pain and opioid use disorder, including their neurobiology 3 and the need for coordinated management. The University of Arizona – College of Medicine Phoenix 4 Use a socio-psycho-biological model to evaluate persons with pain and opioid use disorder. The University of Arizona – College of Medicine Tucson Use a socio-psycho-biological model to develop a whole-person care plan and prevention 5 Mayo Clinic School of Medicine – Arizona Campus strategies for persons with pain and/or opioid use disorder. -

2010 Npr Annual Report About | 02

2010 NPR ANNUAL REPORT ABOUT | 02 NPR NEWS | 03 NPR PROGRAMS | 06 TABLE OF CONTENTS NPR MUSIC | 08 NPR DIGITAL MEDIA | 10 NPR AUDIENCE | 12 NPR FINANCIALS | 14 NPR CORPORATE TEAM | 16 NPR BOARD OF DIRECTORS | 17 NPR TRUSTEES | 18 NPR AWARDS | 19 NPR MEMBER STATIONS | 20 NPR CORPORATE SPONSORS | 25 ENDNOTES | 28 In a year of audience highs, new programming partnerships with NPR Member Stations, and extraordinary journalism, NPR held firm to the journalistic standards and excellence that have been hallmarks of the organization since our founding. It was a year of re-doubled focus on our primary goal: to be an essential news source and public service to the millions of individuals who make public radio part of their daily lives. We’ve learned from our challenges and remained firm in our commitment to fact-based journalism and cultural offerings that enrich our nation. We thank all those who make NPR possible. 2010 NPR ANNUAL REPORT | 02 NPR NEWS While covering the latest developments in each day’s news both at home and abroad, NPR News remained dedicated to delving deeply into the most crucial stories of the year. © NPR 2010 by John Poole The Grand Trunk Road is one of South Asia’s oldest and longest major roads. For centuries, it has linked the eastern and western regions of the Indian subcontinent, running from Bengal, across north India, into Peshawar, Pakistan. Horses, donkeys, and pedestrians compete with huge trucks, cars, motorcycles, rickshaws, and bicycles along the highway, a commercial route that is dotted with areas of activity right off the road: truck stops, farmer’s stands, bus stops, and all kinds of commercial activity. -

University of Phoenix Transfer Guide for Nursing

Block Transfer Pathway for Merced College: Concurrent Enrollment Program Associate in Science Degree in Nursing, Registered 2016-2017 Catalog Bachelor of Science in Nursing v16 Merced College Associate’s Degree Courses 87 Credits Applied* University of Phoenix Bachelor’s Degree UOPX Required Credits BSN Required Course of Study NSG/302 Professional Contemporary Nursing Role and Practice*** 3 NSG/416 Theoretical Development and Conceptual Frameworks*** 3 HSN/376 Health Information Technology for Nursing 3 NSG/451 Professional Nursing Leadership Perspectives*** 3 NSG/456 Research Outcomes Management for the Practicing Nurse 3 NSG/426 Integrity in Practice: Ethic and Legal Considerations*** 3 HSN/476 Healthcare Policy and Financial Management 3 NSG/486CA Public Health: Health Promotion and Disease Prevention 3 NSG/482CA Promoting Healthy Communities 3 NSG/468 Influencing Quality within Healthcare 3 NSG/498 Senior Leadership Practicum 3 Total Credits Summary Required Course of Study Credits Remaining 33 General Education/Elective Credits Applied 47 Lower Division Nursing Credits Applied 40 Credits Remaining to Complete BSN 33 This transfer guide is intended for students enrolled in the Merced College and University of Phoenix Concurrent Enrollment Program (CEP). Students who are not enrolled in the Merced College and University of Phoenix Concurrent Enrollment Program (CEP) should seek advisement from their respective institution if interested in the transferability of other programs. University of Phoenix Associate Degree in Nursing Block Transfer Policy *Effective for new students applying to University of Phoenix on or after 07/01/2017, Students transferring to University of Phoenix into an undergraduate RN to BSN program with a previously completed, regionally or nationally accredited Associate of Arts degree or Associates Degree in Nursing completed from a community college will be considered as satisfying their lower division general education and elective credits. -

Phoenix-Employees.Pdf

What can a degree do for your career? A commitment to lifelong learning ensures that we keep our minds sharp and our skills fresh. University of Phoenix supports that commitment by offering a range of degree programs at the bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral level, as well as certificate programs, professional development, and individual courses. The reasons to pursue higher education are many. Whether your You can select online courses to make learning more flexible with focus is enhancing your current job performance, upward career your schedule, or you can choose to take courses at one of our mobility, personal enrichment, or a combination of the three, local campus locations or learning centers*. Most courses have adding to your knowledge base can help you become a better frequent start dates year-round, and can be completed in as little faculty and staff and give you an extra edge at work and in life. as five to nine weeks. Guiding you through the process will be your Graduation Team, a team of advisors dedicated to supporting Higher education now comes with a lower tuition you from enrollment to graduation. All Shoreline Community College faculty and staff are eligible to receive a 5% tuition savings on bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral Visit phoenix.edu/shorelineemp to learn more. degree programs, as well as certificates and individual courses at University of Phoenix. Experience the University of Phoenix difference University of Phoenix is a fully accredited institution of higher learning. Every one of our hundreds of undergraduate and graduate courses provides you with the real-world experience and insight of our practitioner faculty, small class sizes, and a curriculum that’s industry-aligned and up-to-date. -

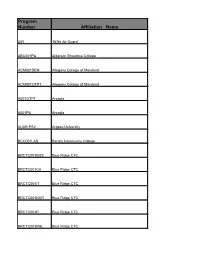

Program Number Affiliation Name

Program Number Affiliation Name AIR 167th Air Guard ABC001PA Alderson Broaddus College ACM001DEN Allegany College of Maryland ACM001OTPT Allegany College of Maryland A001OTPT Arcadia A001PA Arcadia AU001PSY Argosy University BCC001LAB Barton Community College BRCTC001BUS Blue Ridge CTC BRCTC001CA Blue Ridge CTC BRCTC001IT Blue Ridge CTC BRCTC001NUR Blue Ridge CTC BRCTC001P Blue Ridge CTC BRCTC001PHL Blue Ridge CTC BRCTC001PTA Blue Ridge CTC CSU001SLP California State University CCC001PTA Carroll Community College CUA001NUR Catholic University of America CAC001DIET Central Arizona College CCN001NUR Chamberlain College of Nursing CU001PA Chatham University CU001SCI Chatham University CUPA001LIB Clarion University of PA CCAPPA001DIET Community College of Allegheny Pittsburgh PA CU001PHARM Creighton University DEC001CRIM Davis and Elkins College DMU001PUB Des Moines University DU001HIT Devry University DU001NUR Drexel University DU001NP Duquesne University ETSU001NUR East Tennessee State University ECPIU001NUR ECPI University EU001SLP Edinboro University EVCOM001MED Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine EU001PT Elon University FFD001DEN Fairview Family Dentistry FGCU001OT Florida Gulf Coast University FIUI001ECHO Florida Institute of Ultrasound, Inc. FSU001BA Frostburg State University FSU001COM Frostburg State University FSU001NUR Frostburg State University FSU001PSY Frostburg State University FSU001SW Frostburg State University GU001AUD Gallaudet University GWU001NUR George Washington University GWU001OPTH George Washington University -

Arizona Nursing Programs Monthly Meeting Minutes

Arizona Nursing Programs Monthly Meeting Minutes Thursday, December 10, 2020 Meeting convened at 11:01 a.m. by AZBN Staff Hrabe 1) Attendance (Board Staff Dave Hrabe, Cindy George and Kathy Scott present; See Appendix A for list of Attendees) 2) Deans and Directors Education Meetings: a. Information coming soon: Kathy is reviewing topics and will get more information out to you at the beginning of the year. 3) Education Committee: a. Will be reviewing and updating the format/ membership to increase participation from practice settings 4) New fingerprint process (Cindy George) Board is accepting electronic fingerprints. a. Information is on AZBN.ORG website. Students must go all the way through the application and pay. Then they have to select ‘electronic’ fingerprinting which is a separate application. CNAs have been using this mechanism without major problems. https://azbn.gov/licenses-and-certifications/electronic-fingerprint-inst ructions 5) COVID Survey Preliminary Results, Q3 survey (Dave Hrabe) a. Dave Hrabe presented the preliminary results between cohorts graduation pre-pandemic vs cohorts graduating in Q2. The major findings were that the number of virtual/augmented reality hours increased 1061%; direct care clinical hours showed a 26.8% drop in Q2--both were statistically significant (p < .05). 6) NCSBN Education Survey (Dave Hrabe) a. The 2020 Education Survey will be sent early in January. This survey will allow AZ programs to benchmark with other programs across the country. AZ-specific data (e.g. concurrent enrollment programs) will be a part of the survey but analyzed separately. 7) Innovations/Concerns/ Problems a. No issues were identified. -

General Studies

Faculty Credentials College of General Studies This list represents all current University of Phoenix® College of General Studies faculty members who have taught at least one credit-bearing course as the primary faculty member in a degree and/or certificate program between October 1, 2018 and September 30, 2019. Next to each instructor’s name is the year he or she began teaching for University of Phoenix and the highest academic degree earned. Full Name Year First Taught Degree(s) Abel, Suchitra 1992 Doctor Of Philosophy, University Of California - Berkeley Abood, George 2001 Master Of Arts, California State University - Sacramento Abu-Rahmeh, Bassam 2003 Master Of Science, University Of Florida Ach, Kay A 1998 Master Of Public Health, University Of Minnesota - Twin Cities Adachi, Dean 2018 Master Of Business Administration, San Francisco State University Adams, April K 2003 Doctor Of Philosophy, University Of South Florida Adams, Linda R 2007 Master Of Arts, Argosy University - Phoenix; Master Of Education, Northern Arizona University Adrian, Jesus 2011 Doctor Of Philosophy, Universitat Autonoma De Barcelona Afseth, Daniel L 1996 Master Of Science, The University Of Texas At El Paso Afshar, Melanie 2013 Doctor Of Psychology, Pepperdine University Agard, Christopher B 2008 Master Of Science, California Baptist University Agena, Diane K 2009 Doctor Of Philosophy, Purdue University Ajana, Hadley T 2009 Juris Doctorate, Thomas Jefferson School Of Law Alastuey, Lisa L 2009 Doctor Of Education, Texas A&M University - Commerce Alder, Cathie -

Section VII Distribution and List of Participating Schools

Section VII Distribution and List of Participating Schools Vice Presidents of Chancellors & State School and Location Adm. & Facilities Total Presidents Survey Survey AK University of Alaska Southeast, Juneau ● Total 0 1 1 AL Alabama Agricultural and Mechanical University, Normal ● Athens State University, Athens ● Auburn University, Montgomery ● Auburn University, Auburn ● Calhoun Community College, Decatur ● ● Chattahoochee Valley Community College, Phenix City ● Enterprise-Ozark Community College, Enterprise ● Gadsden State Community College, Gadsden ● J.F. Drake State Technical College, Huntsville ● Jefferson Davis Community College, Brewton ● Spring Hill College, Mobile ● Stillman College, Tuscaloosa ● Troy University, Troy ● ● United States Sports Academy, Daphne ● University of West Alabama, Livingston ● Total 12 5 17 AR Arkansas State University, Newport ● ● Cossatot Community College of the University of Arkansas, De Queen ● East Arkansas Community College, Forrest City ● Henderson State University, Arkadelphia ● North Arkansas College, Harrison ● NorthWest Arkansas Community College, Bentonville ● Ozarka College, Melbourne ● South Arkansas Community College, El Dorado ● Southern Arkansas University Tech, Camden ● University of Arkansas, Monticello ● University of Arkansas, Pine Bluff ● University of Arkansas Community College, Batesville ● Total 6 7 13 AZ Arizona State University, Tempe ● ● Arizona Western College, Yuma ● Central Arizona College, Coolidge ● Chandler-Gilbert Community College, Chandler ● Coconino County Community -

University of Phoenix (A Subsidiary of the Apollo Group)

University of Phoenix (a subsidiary of The Apollo Group) LAST UPDATED NOVEMBER 2002 BACKGROUND - For two excellent, in-depth articles on the privatization of Education, please see: A. Summa cum avaritia: plucking a profit from the groves of academe , Nick Bromell, Harper’s Magazine, February 2002. B. Us Versus Them: Laboring in the Academic Factory , Michael Yates, Monthly Review, January 2000. Click ahead to the Economic Profile section Click ahead to the Political Profile section Click ahead to the Social Profile section Click ahead to the Quotations section (For background information on how these sections are organized, click here ) 1. Organizational Profile The University of Phoenix is a private university with campuses throughout the United States and in British Columbia, Canada. They offer courses in business, information technology, health care services and others. They offer low wages and standardized courses as a means to keep costs low and make very high profits. They are looking to expand internationally and they use their clout as members of the US Based National Committee for International Trade in Education (NCITE) to do so. NCITE is an organization which, as a member body of the US Coalition of Services Industries , pushes for easy cross-border trade in Education through use of trade agreements such as the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS). As well, the University of Phoenix has had a serious effect on the outlook of other University systems. According to an article in the Times Higher Educational Supplement, the “extraordinary growth” of the University of Phoenix has “persuaded officials at traditional American institutions of the one-time heresy that higher education is a market – a commodity that responds to differences among schools in such variables as cost and convenience.” In the words of former Phoenix President William Gibbs “the people who are our students don’t want an education. -

Reining in the Predatory Nature of For-Profit Colleges

REINING IN THE PREDATORY NATURE OF FOR-PROFIT COLLEGES Sarah Ann Schade* Despite the alarming growth of for-profit colleges in recent years, such colleges are not exempt from harsh and relentless criticisms, ranging from alleged unethical recruiting practices to exorbitant, unparalleled tuition costs. This Note exposes the predatory practices of for-profit colleges, where for-profit colleges target vulnerable populations, particularly the poor and minorities; provide low quality education, exemplified through abysmal graduation rates and a general lack of postgraduate employment opportunities; conduct frivolous spending focused primarily on marketing and executive salaries; and leave students with unprecedented levels of nondischargeable debt. This Note addresses potential public and private remedies for addressing abuses by for-profit colleges and proposes several federal, state-specific, and individual solutions, arguing that various federal proposals should be adopted, states should continue to pass effective legislation, and qui tam whistleblower actions should be encouraged and facilitated. The United States must take a stand against the predatory nature of for-profit colleges to preserve the integrity and future of America’s higher education system. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 318 I. THE FOR-PROFIT COLLEGE BUSINESS MODEL .................................................. 322 A. Marketing Toward Vulnerable Populations ..............................................