Asia Center Odawara

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Exponent of Breath: The Role of Foreign Evangelical Organizations in Combating Japan's Tuberculosis Epidemic of the Early 20th Century Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/32d241sf Author Perelman, Elisheva Avital Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Exponent of Breath: The Role of Foreign Evangelical Organizations in Combating Japan’s Tuberculosis Epidemic of the Early 20th Century By Elisheva Avital Perelman A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Andrew E. Barshay, Chair Professor John Lesch Professor Alan Tansman Fall 2011 © Copyright by Elisheva Avital Perelman 2011 All Rights Reserved Abstract The Role of Foreign Evangelical Organizations in Combating Japan’s Tuberculosis Epidemic of the Early 20th Century By Elisheva Avital Perelman Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Andrew E. Barshay, Chair Tuberculosis existed in Japan long before the arrival of the first medical missionaries, and it would survive them all. Still, the epidemic during the period from 1890 until the 1920s proved salient because of the questions it answered. This dissertation analyzes how, through the actions of the government, scientists, foreign evangelical leaders, and the tubercular themselves, a nation defined itself and its obligations to its subjects, and how foreign evangelical organizations, including the Young Men’s Christian Association (the Y.M.C.A.) and The Salvation Army, sought to utilize, as much as to assist, those in their care. -

An Analysis of Edward S. Morse's Japan Day by Day Karl Bazzocchi Mcgill University December, 2006

A Westerner's Journey in Japan: An Analysis of Edward S. Morse's Japan Day By Day Karl Bazzocchi McGill University December, 2006 A thesis submitted to Mc Gill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts. © Karl Bazzocchi, 2006. Libraryand Bibliothèque et 1+1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-38444-2 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-38444-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, électronique commercial purposes, in microform, eUou autres formats. paper, electranic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Kavli IPMU Annual 2014 Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2014 REPORT ANNUAL April 2014–March 2015 2014–March April Kavli IPMU Kavli Kavli IPMU Annual Report 2014 April 2014–March 2015 CONTENTS FOREWORD 2 1 INTRODUCTION 4 2 NEWS&EVENTS 8 3 ORGANIZATION 10 4 STAFF 14 5 RESEARCHHIGHLIGHTS 20 5.1 Unbiased Bases and Critical Points of a Potential ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙20 5.2 Secondary Polytopes and the Algebra of the Infrared ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙21 5.3 Moduli of Bridgeland Semistable Objects on 3- Folds and Donaldson- Thomas Invariants ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙22 5.4 Leptogenesis Via Axion Oscillations after Inflation ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙23 5.5 Searching for Matter/Antimatter Asymmetry with T2K Experiment ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ 24 5.6 Development of the Belle II Silicon Vertex Detector ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙26 5.7 Search for Physics beyond Standard Model with KamLAND-Zen ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙28 5.8 Chemical Abundance Patterns of the Most Iron-Poor Stars as Probes of the First Stars in the Universe ∙ ∙ ∙ 29 5.9 Measuring Gravitational lensing Using CMB B-mode Polarization by POLARBEAR ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ 30 5.10 The First Galaxy Maps from the SDSS-IV MaNGA Survey ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙32 5.11 Detection of the Possible Companion Star of Supernova 2011dh ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ -

Tourist Information Venture Forth Into the Streets on Your Own So That You May Feel Center

TOKYO WALKS PAGE 1 / 10 Practical Travel Guide - 305 TOKYO WALKS There are many ways to see Tokyo as it is a huge metropolis first-hand the pulse of one of the world’s most bustling cities. with a population of nearly 12 million where older traditions and Given herein are several recommended walking tours of Tokyo. newer fashions have been interacting harmoniously for four cen- If you wish more detailed information on each of the places of turies. One of the most recommendable ways, however, is to interest, please feel free to contact JNTO’s Tourist Information venture forth into the streets on your own so that you may feel Center. IMPERIAL PALACE AND KITANOMARU PARK Imperial Palace and Kitanomaru Park Yasukuni Shrine 靖国神社 Tourist Information Japan Railways (JR) H British Embassy National Diamond Hotel Shinkansen Theatre Subway Lines 国立劇場 Moats Tayasumon Gate 田安門 ●⑩ 0 200m Hanzomon Gate Chidorigafuchi 半蔵門 ●⑦ Nippon 千鳥が淵 Kitanomaru ●⑨ Budokan Hall Park 日本武道館 ●⑪ 北の丸公園 Kudanshita Sta. Imperial Palace Crafts Gallery 九段下駅 皇居 工芸館 Yurakucho Line 有楽町線 ●⑧ Science Museum Tozai Line 科学技術館 東西線 ●⑫ ●⑥ National Museum of Modern Art Kita-Hanebashimon Gate 東京国立近代美術館 北桔橋門 Imperial Household ●⑬ Sakuradamon Sta. Agency宮内庁 桜田門駅 Takebashi Sta. Metropolitan Sakuradamon Gate Higashi Gyoen 竹橋駅 桜田門 Police Department Nijubashi Bridge 東御苑 Mainichi Newspapers ●③ 二重橋 ●⑤ 毎日新聞社 Hirakawamon Gate Hibiya Line 平川門 日 比谷線 Sannomaru Shozokan ●② 宮内庁三の丸尚蔵館 Hibiya Park Imperial Kikkyomon Gate 日比谷公園 Palace Plaza Hanzomon Line 桔梗門 半蔵門線 皇居前広場 N ●④ Otemon Gate 大手門 Toei-Mita Line H Palace Hotel パレスホテルパレスホテル Hibiya Sta. 都営三田線 日比谷駅 Chiyoda Line Otemachi Sta. Otemachi Sta. TIC, JNTO Nijubashi-mae Sta. -

LIST of the WOOD PACKAGING MATERIAL PRODUCER for EXPORT 2007/2/10 Registration Number Registered Facility Address Phone

LIST OF THE WOOD PACKAGING MATERIAL PRODUCER FOR EXPORT 2007/2/10 Registration number Registered Facility Address Phone 0001002 ITOS CORPORATION KAMOME-JIGYOSHO 62-1 KAMOME-CHO NAKA-KU YOKOHAMA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-622-1421 ASAGAMI CORPORATION YOKOHAMA BRANCH YAMASHITA 0001004 279-10 YAMASHITA-CHO NAKA-KU YOKOHAMA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-651-2196 OFFICE 0001007 SEITARO ARAI & CO., LTD. TORIHAMA WAREHOUSE 12-57 TORIHAMA-CHO KANAZAWA-KU YOKOHAMA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-774-6600 0001008 ISHIKAWA CO., LTD. YOKOHAMA FACTORY 18-24 DAIKOKU-CHO TSURUMI-KU YOKOHAMA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-521-6171 0001010 ISHIWATA SHOTEN CO., LTD. 4-13-2 MATSUKAGE-CHO NAKA-KU YOKOHAMA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-641-5626 THE IZUMI EXPRESS CO., LTD. TOKYO BRANCH, PACKING 0001011 8 DAIKOKU-FUTO TSURUMI-KU YOKOHAMA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-504-9431 CENTER C/O KOUEI-SAGYO HONMOKUEIGYOUSHO, 3-1 HONMOKU-FUTO NAKA-KU 0001012 INAGAKI CO., LTD. HONMOKU B-2 CFS 045-260-1160 YOKOHAMA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 0001013 INOUE MOKUZAI CO., LTD. 895-3 SYAKE EBINA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 046-236-6512 0001015 UTOC CORPORATION T-1 OFFICE 15 DAIKOKU-FUTO TSURUMI-KU YOKOHAMA-SHI KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-501-8379 0001016 UTOC CORPORATION HONMOKU B-1 OFFICE B-1, HONMOKU-FUTOU, NAKA-KU, YOKOHAMA-SHI, KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-621-5781 0001017 UTOC CORPORATION HONMOKU D-5 CFS 1-16, HONMOKU-FUTOU, NAKA-KU, YOKOHAMA-SHI, KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-623-1241 0001018 UTOC CORPORATION HONMOKU B-3 OFFICE B-3, HONMOKU-FUTOU, NAKA-KU, YOKOHAMA-SHI, KANAGAWA, JAPAN 045-621-6226 0001020 A.B. SHOUKAI CO., LTD. -

Addressing Europe's Unfinished Business

27-28 June 2014 Addressing Europe’s Unfinished Business through an action for a more peaceful, more united Europe The Foundation CAUX-Initiatives of Change invites you to a Seminar from 27 June 2014 at 10h00 to 28 June 2014 at 17h00 at the International Conference Center in Caux (Montreux, Switzerland). This seminar will include leading politicians, historians and thinkers and will reflect on how to foster a new European spirit across Europe. The 100th memorial of the start of WWI and the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin wall is a unique occasion for European-minded political leaders, historians and thinkers to address Europe's unfinished business. During this seminar, four workshops will be organised to share the best of the participants’ experience and vision, and to design Europe's unfinished business means the lack of articulation new initiatives: of the European project in accessible language and the lack of fostering a European spirit by way of European history school Changing Paradigms in the Eastern Regions of Europe: eliminating age-old rivalries, acknowledging Russia and Turkey as key textbooks, frequent joint war commemorations and contributors to Europe’s past and future, which “creative efforts” appropriate celebrations on the Day of Europe each 9 May. Is are needed to lastingly pacify those regions? this situation not an open door for nationalist revivals? The Challenge of Immigration: in spite of the Schuman Europe's unfinished business means unresolved cross- declaration’s intentions, economic imbalances have continued and are leading to massive migrations which challenge identities. border or dormant internal regional conflicts, unhealed Envisioning initiatives to raise the standard of living in poorer wounds which have caused a string of armed conflicts in countries, and initiatives for smoother integration of “newcomers” Europe over the last 25 years. -

Propaganda Theatre : a Critical and Cultural Examination of the Work Of

ANGLIA RUSKIN UNIVERSITY PROPAGANDA THEATRE: A CRITICAL AND CULTURAL EXAMINATION OF THE WORK OF MORAL RE-ARMAMENT AT THE WESTMINSTER THEATRE, LONDON. PAMELA GEORGINA JENNER A thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Anglia Ruskin University for the degree of PhD Submitted: June 2016 i Acknowledgements I am grateful to Anglia Ruskin University (ARU) for awarding me a three-year bursary in order to research this PhD. My thanks also go to my supervisory team: first supervisor Dr Susan Wilson, second supervisor Dr Nigel Ward, third supervisor Dr Jonathan Davis, fourth supervisor Dr Aldo Zammit-Baldo and also to IT advisor at ARU, Peter Carlton. I am indebted to Initiatives of Change for permission to access and publish material from its archives and in particular to contributions from IofC supporters including Hilary Belden, Dr Philip Boobbyer, Christine Channer, Fiona Daukes, Anne Evans, Chris Evans, David Hassell, Kay Hassell, Michael Henderson Stanley Kiaer, David Locke, Elizabeth Locke, John Locke; also to the late Louis Fleming and Hugh Steadman Williams. Without their enthusiasm and unfailing support this thesis could not have been written. I would also like to thank my family, Daniel, Moses and Richard Brett and Sanjukta Ghosh for their ongoing support. ii ANGLIA RUSKIN UNIVERSITY ABSTRACT FACULTY OF ARTS, LAW AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROPAGANDA THEATRE: A CRITICAL AND CULTURAL EXAMINATION OF THE WORK OF MORAL RE-ARMAMENT AT THE WESTMINSTER THEATRE, LONDON PAMELA GEORGINA JENNER JUNE 2016 This thesis investigates the rise and fall of the propagandist theatre of Moral Re-Armament (MRA), which owned the Westminster Theatre in London, from 1946 to 1997. -

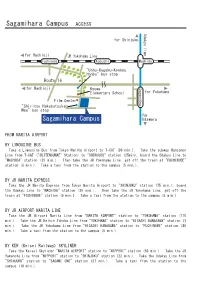

Sagamihara Campus ACCESS Odakyu Line

Sagamihara Campus ACCESS Odakyu line for Shinjuku for Hachioji JR Yokohama Line Fuchinobe Kobuchi Machida "Uchu-Kagaku-Kenkyu Honbu" bus stop Route 16 for Hachioji Kyowa SagamiOno Elementary School for Yokohama Film Center "Shiritsu Hakubutsukan Mae" bus stop for Sagamihara Campus Odawara FROM NARITA AIRPORT BY LIMOUSINE BUS Take a Limousine Bus from Tokyo Narita Airport to T-CAT (90 min.). Take the subway Hanzomon Line from T-CAT ("SUITENGUMAE" Station) to "SHINJUKU" station (25min), board the Odakyu Line to "MACHIDA" station (35 min.). Then take the JR Yokohama Line, get off the train at "FUCHINOBE" station (6 min.). Take a taxi from the station to the campus (5 min.). BY JR NARITA EXPRESS Take the JR Narita Express from Tokyo Narita Airport to "SHINJUKU" station (75 min.), board the Odakyu Line to "MACHIDA" station (35 min.). Then take the JR Yokohama Line, get off the train at "FUCHINOBE" station (6 min.). Take a taxi from the station to the campus (5 min.). BY JR AIRPORT NARITA LINE Take the JR Airport Narita Line from "NARITA AIRPORT" station to "YOKOHAMA" station (110 min.). Take the JR Keihin Tohoku Line from "YOKOHAMA" station to "HIGASHI KANAGAWA" station (3 min.). Take the JR Yokohama Line from "HIGASHI KANAGAWA" station to "FUCHINOBE" station (40 min.). Take a taxi from the station to the campus (5 min.). BY KER (Keisei Railway) SKYLINER Take the Keisei Skyliner "NARITA AIRPORT" station to "NIPPORI" station (50 min.). Take the JR Yamanote Line from "NIPPORI" station to "SHINJUKU" station (22 min.). Take the Odakyu Line from "SHINJUKU" station to "SAGAMI ONO" station (37 min.). -

![Inbound [Daily Train Service] for Ito, Atami and Tokyo *Some Trains Operate on Weekdays](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6295/inbound-daily-train-service-for-ito-atami-and-tokyo-some-trains-operate-on-weekdays-966295.webp)

Inbound [Daily Train Service] for Ito, Atami and Tokyo *Some Trains Operate on Weekdays

Inbound [Daily train service] For Ito, Atami and Tokyo *Some trains operate on weekdays. (To Atami) (To Atami) Odoriko No.106 Odoriko No.108 Super Super Resort 21 Resort 21 Odoriko Odoriko Train Name View View No.2 No.8 Destination Ito Ito Ito Atami Izu-Kogen Atami Ito Ito Izu-Kogen Atami Atami Atami Tokyo Atami Atami Atami Tokyo Atami Tokyo Atami Atami Atami Tokyo Train No. of Izukyuko Line 624 626 702 5628M 630 5630M 632 634 636 5636M 5638M 5640M 3002M 5642M 5644M 5646M 3026M 5648M 3028M 5650M 5652M 5654M 3008M Izukyu-shimoda (Dept.) - - - 539 607 634 - 701 735 808 - 856 934 1004 1017 ┐( 1042 1132 1212 1222 1303 - 1317 1351 1409 May operate using other trains.) Rendaiji 〃〃 - - - 543 611 638 - 704 739 812 - 859 938 * 1020 1046 1136 * 1225 * - 1327 1355 * Inazusa 〃〃 - - - 547 615 642 - 708 742 815 - 903 943 * 1025 1049 1141 * 1231 * - 1331 1402 * Izukyuko Line Kawazu 〃〃 - - - 554 621 648 - 715 750 821 - 909 948 1018 1031 1101 1148 1225 1237 1318 - 1339 1408 1424 Imaihama-kaigan 〃〃 - - - 556 623 650 - 717 752 823 - 912 951 * 1033 1103 1150 * 1239 * - 1342 1411 * Izu-inatori 〃〃 - - - 601 628 655 - 721 759 831 - 916 955 1024 1037 1108 1155 1230 1244 1324 - 1350 1418 1430 Katase-shirata 〃〃 - - - 606 633 701 - 727 804 836 - 921 1000 * 1044 1113 1159 * 1250 * - 1355 1424 * Izu-atagawa 〃〃 - - - 609 636 704 - 732 808 840 - 924 1004 1031 1049 1116 1202 1237 1255 1332 - 1358 1427 1437 Izu-hokkawa 〃〃 - - - 612 639 706 - 734 811 842 - 926 1007 * 1051 1118 1205 * 1258 * - 1401 1430 * Izu-okawa 〃〃 - - - 615 642 709 - 737 817 848 - 929 1010 * 1054 1126 -

Chigasaki Breeze

International Association of Chigasaki (IAC) March 1, 2012 Bimonthly Publication Chigasaki Breeze Truly great friends are hard to find, difficult to leave, and impossible to forget. No.39 No.38 だいさいがい そな Let’s Prepare for Potential Disasters! 大災害に備えよう Nearly one year has passed since the Great East Japan Earthquake occurred. Are you still on the alert? If a big earthquake hit Chigasaki, more than ten thousand houses would be expected to collapse, about fifty fires would break out, and an eight-meter high tsunami could reach the coast within minutes, according to simulations by the prefecture. As it may take three days until the first rescue corps arrive in the city, residents will have to live in difficult circumstances during this initial period. Be prepared for natural disasters. Warning: ❶When an earthquake exceeding five minor on the Japanese seismic scale occurs, or a tsunami is predicted, emergency messages are announced from public speakers throughout the city. When you hear the message, “Kochira wa bousai Chigasaki desu.” meaning this is a public - emergency warning, or “Tsunami keihou desu.” meaning this is a tsunami warning, please listen carefully and ask nearby Japanese people what the message means. ❷Instructions from the city can be obtained from the City web site in eight languages, public speakers, Twitter and mobile phone email services. Evacuation facilities: ❶The number of temporary tsunami evacuation sites is 75 as of February 20. When a tsunami evacuation warning is issued, people should rush to the nearest (temporary or long-term) site. Evacuees at temporary sites should then move to longer-term evacuation sites (see ❸ below) once it has been confirmed that it is safe. -

Factura Nº 1/2009

High Level Meeting on the right to peace Organised by Costa Rica in coordination with CSOs and the support of the Non-governmental Liaison Unit of UNOG IN THE CONTEXT OF THE COMMEMORATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL DAY OF PEACE: "SUSTAINABLE PEACE FOR A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE" High level Meeting on The Right to Peace Geneva, 21rst September 2012 Palais des Nations 13:10 - 14:10 h. Room XVI Report prepared by: David Fernández Puyana1 1. Representative in Geneva of the Spanish Society for International Human Rights Law, the International Observatory of the Human Right to Peace and the International Association of Peace Messenger Cities. In the context of the Commemoration of the International Day of Peace. Geneva, 21rst September 2012 High Level Meeting on the right to peace Organised by Costa Rica in coordination with CSOs and the support of the Non-governmental Liaison Unit of UNOG Index 1. Introduction. 2. Background. 3. Commemoration. 4. Presentations. 5. Annexes 1. Introduction The International Day of Peace, also known as the World Peace Day, occurs annually on 21 September. It is dedicated to peace, and, specifically, to the absence of war, and the Secretary-General calls for a temporary ceasefire in a combat zone. It is observed by many nations, political groups, military groups and peoples. This year marked the 31rst anniversary of the adoption of resolution 36/67 (1981) and 11 years since the adoption of resolution 55/282 (2001) on the International Day of Peace by the General Assembly. Costa Rica not only recognizes the International Day of Peace, but was also the sponsor of the original resolution establishing the Day in 1981 and 2001 before the General Assembly. -

The Steel Butterfly: Aung San Suu Kyi Democracy Movement in Burma

presents The Steel Butterfly: Aung San Suu Kyi and the Democracy Movement in Burma Photo courtesy of First Post Voices Against Indifference Initiative 2012-2013 Dear Teachers, As the world watches Burma turn toward democracy, we cannot help but wish to be part of this historic movement; to stand by these citizens who long for justice and who so richly deserve to live in a democratic society. For 25 years, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi endured house arrest because of her unwavering belief in, and fight for, democracy for all the people of Burma. Through her peaceful yet tireless example, Madam Suu Kyi has demonstrated the power of the individual to change the course of history. Now, after 22 years, the United States of America has reopened diplomatic relations with Burma. President Barack Obama visited in November 2012, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton visited in December 2011 and, in July of 2012, Derek Mitchell was appointed to represent our country as Ambassador to Burma. You who are the teachers of young people, shape thinking and world views each day, directly or subtly, in categories of learning that cross all boundaries. The Echo Foundation thanks you for your commitment to creating informed, compassionate, and responsible young people who will lead us into the future while promoting respect, justice and dignity for all people. With this curriculum, we ask you to teach your students about Burma, the Burmese people, and their leader, Aung San Suu Kyi. The history of Burma is fascinating. Long in the margins of traditional studies, it deserves to come into the light so that we may join the people of Burma in their quest for a stable democracy.