An Analytical Theory for the Perturbative Effect of Solar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Utilization of Halo Orbit§ in Advanced Lunar Operation§

NASA TECHNICAL NOTE NASA TN 0-6365 VI *o M *o d a THE UTILIZATION OF HALO ORBIT§ IN ADVANCED LUNAR OPERATION§ by Robert W. Fmqcbar Godddrd Spctce Flight Center P Greenbelt, Md. 20771 NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION WASHINGTON, D. C. JULY 1971 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. NASA TN D-6365 5. Report Date Jul;v 1971. 6. Performing Organization Code 8. Performing Organization Report No, G-1025 10. Work Unit No. Goddard Space Flight Center 11. Contract or Grant No. Greenbelt, Maryland 20 771 13. Type of Report and Period Covered 2. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address Technical Note J National Aeronautics and Space Administration Washington, D. C. 20546 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 5. Supplementary Notes 6. Abstract Flight mechanics and control problems associated with the stationing of space- craft in halo orbits about the translunar libration point are discussed in some detail. Practical procedures for the implementation of the control techniques are described, and it is shown that these procedures can be carried out with very small AV costs. The possibility of using a relay satellite in.a halo orbit to obtain a continuous com- munications link between the earth and the far side of the moon is also discussed. Several advantages of this type of lunar far-side data link over more conventional relay-satellite systems are cited. It is shown that, with a halo relay satellite, it would be possible to continuously control an unmanned lunar roving vehicle on the moon's far side. Backside tracking of lunar orbiters could also be realized. -

Low Thrust Manoeuvres to Perform Large Changes of RAAN Or Inclination in LEO

Facoltà di Ingegneria Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Ingegneria Aerospaziale Master Thesis Low Thrust Manoeuvres To Perform Large Changes of RAAN or Inclination in LEO Academic Tutor: Prof. Lorenzo CASALINO Candidate: Filippo GRISOT July 2018 “It is possible for ordinary people to choose to be extraordinary” E. Musk ii Filippo Grisot – Master Thesis iii Filippo Grisot – Master Thesis Acknowledgments I would like to address my sincere acknowledgments to my professor Lorenzo Casalino, for your huge help in these moths, for your willingness, for your professionalism and for your kindness. It was very stimulating, as well as fun, working with you. I would like to thank all my course-mates, for the time spent together inside and outside the “Poli”, for the help in passing the exams, for the fun and the desperation we shared throughout these years. I would like to especially express my gratitude to Emanuele, Gianluca, Giulia, Lorenzo and Fabio who, more than everyone, had to bear with me. I would like to also thank all my extra-Poli friends, especially Alberto, for your support and the long talks throughout these years, Zach, for being so close although the great distance between us, Bea’s family, for all the Sundays and summers spent together, and my soccer team Belfiga FC, for being the crazy lovable people you are. A huge acknowledgment needs to be address to my family: to my grandfather Luciano, for being a great friend; to my grandmother Bianca, for teaching me what “fighting” means; to my grandparents Beppe and Etta, for protecting me -

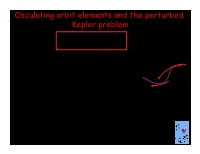

Osculating Orbit Elements and the Perturbed Kepler Problem

Osculating orbit elements and the perturbed Kepler problem Gmr a = 3 + f(r, v,t) Same − r x & v Define: r := rn ,r:= p/(1 + e cos f) ,p= a(1 e2) − osculating orbit he sin f h v := n + λ ,h:= Gmp p r n := cos ⌦cos(! + f) cos ◆ sinp ⌦sin(! + f) e − X +⇥ sin⌦cos(! + f) + cos ◆ cos ⌦sin(! + f⇤) eY actual orbit +sin⇥ ◆ sin(! + f) eZ ⇤ λ := cos ⌦sin(! + f) cos ◆ sin⌦cos(! + f) e − − X new osculating + sin ⌦sin(! + f) + cos ◆ cos ⌦cos(! + f) e orbit ⇥ − ⇤ Y +sin⇥ ◆ cos(! + f) eZ ⇤ hˆ := n λ =sin◆ sin ⌦ e sin ◆ cos ⌦ e + cos ◆ e ⇥ X − Y Z e, a, ω, Ω, i, T may be functions of time Perturbed Kepler problem Gmr a = + f(r, v,t) − r3 dh h = r v = = r f ⇥ ) dt ⇥ v h dA A = ⇥ n = Gm = f h + v (r f) Gm − ) dt ⇥ ⇥ ⇥ Decompose: f = n + λ + hˆ R S W dh = r λ + r hˆ dt − W S dA Gm =2h n h + rr˙ λ rr˙ hˆ. dt S − R S − W Example: h˙ = r S d (h cos ◆)=h˙ e dt · Z d◆ h˙ cos ◆ h sin ◆ = r cos(! + f)sin◆ + r cos ◆ − dt − W S Perturbed Kepler problem “Lagrange planetary equations” dp p3 1 =2 , dt rGm 1+e cos f S de p 2 cos f + e(1 + cos2 f) = sin f + , dt Gm R 1+e cos f S r d◆ p cos(! + f) = , dt Gm 1+e cos f W r d⌦ p sin(! + f) sin ◆ = , dt Gm 1+e cos f W r d! 1 p 2+e cos f sin(! + f) = cos f + sin f e cot ◆ dt e Gm − R 1+e cos f S− 1+e cos f W r An alternative pericenter angle: $ := ! +⌦cos ◆ d$ 1 p 2+e cos f = cos f + sin f dt e Gm − R 1+e cos f S r Perturbed Kepler problem Comments: § these six 1st-order ODEs are exactly equivalent to the original three 2nd-order ODEs § if f = 0, the orbit elements are constants § if f << Gm/r2, use perturbation theory -

Astrodynamics

Politecnico di Torino SEEDS SpacE Exploration and Development Systems Astrodynamics II Edition 2006 - 07 - Ver. 2.0.1 Author: Guido Colasurdo Dipartimento di Energetica Teacher: Giulio Avanzini Dipartimento di Ingegneria Aeronautica e Spaziale e-mail: [email protected] Contents 1 Two–Body Orbital Mechanics 1 1.1 BirthofAstrodynamics: Kepler’sLaws. ......... 1 1.2 Newton’sLawsofMotion ............................ ... 2 1.3 Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation . ......... 3 1.4 The n–BodyProblem ................................. 4 1.5 Equation of Motion in the Two-Body Problem . ....... 5 1.6 PotentialEnergy ................................. ... 6 1.7 ConstantsoftheMotion . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .... 7 1.8 TrajectoryEquation .............................. .... 8 1.9 ConicSections ................................... 8 1.10 Relating Energy and Semi-major Axis . ........ 9 2 Two-Dimensional Analysis of Motion 11 2.1 ReferenceFrames................................. 11 2.2 Velocity and acceleration components . ......... 12 2.3 First-Order Scalar Equations of Motion . ......... 12 2.4 PerifocalReferenceFrame . ...... 13 2.5 FlightPathAngle ................................. 14 2.6 EllipticalOrbits................................ ..... 15 2.6.1 Geometry of an Elliptical Orbit . ..... 15 2.6.2 Period of an Elliptical Orbit . ..... 16 2.7 Time–of–Flight on the Elliptical Orbit . .......... 16 2.8 Extensiontohyperbolaandparabola. ........ 18 2.9 Circular and Escape Velocity, Hyperbolic Excess Speed . .............. 18 2.10 CosmicVelocities -

Orbit Determination Methods and Techniques

PROJECTE FINAL DE CARRERA (PFC) GEOSAR Mission: Orbit Determination Methods and Techniques Marc Fernàndez Uson PFC Advisor: Prof. Antoni Broquetas Ibars May 2016 PROJECTE FINAL DE CARRERA (PFC) GEOSAR Mission: Orbit Determination Methods and Techniques Marc Fernàndez Uson ABSTRACT ABSTRACT Multiple applications such as land stability control, natural risks prevention or accurate numerical weather prediction models from water vapour atmospheric mapping would substantially benefit from permanent radar monitoring given their fast evolution is not observable with present Low Earth Orbit based systems. In order to overcome this drawback, GEOstationary Synthetic Aperture Radar missions (GEOSAR) are presently being studied. GEOSAR missions are based on operating a radar payload hosted by a communication satellite in a geostationary orbit. Due to orbital perturbations, the satellite does not follow a perfectly circular orbit, but has a slight eccentricity and inclination that can be used to form the synthetic aperture required to obtain images. Several sources affect the along-track phase history in GEOSAR missions causing unwanted fluctuations which may result in image defocusing. The main expected contributors to azimuth phase noise are orbit determination errors, radar carrier frequency drifts, the Atmospheric Phase Screen (APS), and satellite attitude instabilities and structural vibration. In order to obtain an accurate image of the scene after SAR processing, the range history of every point of the scene must be known. This fact requires a high precision orbit modeling and the use of suitable techniques for atmospheric phase screen compensation, which are well beyond the usual orbit determination requirement of satellites in GEO orbits. The other influencing factors like oscillator drift and attitude instability, vibration, etc., must be controlled or compensated. -

Rendezvous Design in a Cislunar Near Rectilinear Halo Orbit Emmanuel Blazquez, Laurent Beauregard, Stéphanie Lizy-Destrez, Finn Ankersen, Francesco Capolupo

Rendezvous Design in a Cislunar Near Rectilinear Halo Orbit Emmanuel Blazquez, Laurent Beauregard, Stéphanie Lizy-Destrez, Finn Ankersen, Francesco Capolupo To cite this version: Emmanuel Blazquez, Laurent Beauregard, Stéphanie Lizy-Destrez, Finn Ankersen, Francesco Capolupo. Rendezvous Design in a Cislunar Near Rectilinear Halo Orbit. International Symposium on Space Flight Dynamics (ISSFD), Feb 2019, Melbourne, Australia. pp.1408-1413. hal-03200239 HAL Id: hal-03200239 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03200239 Submitted on 16 Apr 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Open Archive Toulouse Archive Ouverte (OATAO) OATAO is an open access repository that collects the wor of some Toulouse researchers and ma es it freely available over the web where possible. This is an author's version published in: h ttps://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/22865 To cite this version : Blazquez, Emmanuel and Beauregard, Laurent and Lizy-Destrez, Stéphanie and Ankersen, Finn and Capolupo, Francesco Rendezvous Design in a Cislunar Near Rectilinear Halo Orbit. -

Orbit Options for an Orion-Class Spacecraft Mission to a Near-Earth Object

Orbit Options for an Orion-Class Spacecraft Mission to a Near-Earth Object by Nathan C. Shupe B.A., Swarthmore College, 2005 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Aerospace Engineering Sciences 2010 This thesis entitled: Orbit Options for an Orion-Class Spacecraft Mission to a Near-Earth Object written by Nathan C. Shupe has been approved for the Department of Aerospace Engineering Sciences Daniel Scheeres Prof. George Born Assoc. Prof. Hanspeter Schaub Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Shupe, Nathan C. (M.S., Aerospace Engineering Sciences) Orbit Options for an Orion-Class Spacecraft Mission to a Near-Earth Object Thesis directed by Prof. Daniel Scheeres Based on the recommendations of the Augustine Commission, President Obama has pro- posed a vision for U.S. human spaceflight in the post-Shuttle era which includes a manned mission to a Near-Earth Object (NEO). A 2006-2007 study commissioned by the Constellation Program Advanced Projects Office investigated the feasibility of sending a crewed Orion spacecraft to a NEO using different combinations of elements from the latest launch system architecture at that time. The study found a number of suitable mission targets in the database of known NEOs, and pre- dicted that the number of candidate NEOs will continue to increase as more advanced observatories come online and execute more detailed surveys of the NEO population. -

Radiation Forces on Small Particles in the Solar System T

1CARUS 40, 1-48 (1979) Radiation Forces on Small Particles in the Solar System t JOSEPH A. BURNS Cornell University, 2 Ithaca, New York 14853 and NASA-Ames Research Center PHILIPPE L. LAMY CNRS-LAS, Marseille, France 13012 AND STEVEN SOTER Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853 Received May 12, 1978; revised May 2, 1979 We present a new and more accurate expression for the radiation pressure and Poynting- Robertson drag forces; it is more complete than previous ones, which considered only perfectly absorbing particles or artificial scattering laws. Using a simple heuristic derivation, the equation of motion for a particle of mass m and geometrical cross section A, moving with velocity v through a radiation field of energy flux density S, is found to be (to terms of order v/c) mi, = (SA/c)Qpr[(1 - i'/c)S - v/c], where S is a unit vector in the direction of the incident radiation,/" is the particle's radial velocity, and c is the speed of light; the radiation pressure efficiency factor Qpr ~ Qabs + Q~a(l - (cos a)), where Qabs and Q~c~ are the efficiency factors for absorption and scattering, and (cos a) accounts for the asymmetry of the scattered radiation. This result is confirmed by a new formal derivation applying special relativistic transformations for the incoming and outgoing energy and momentum as seen in the particle and solar frames of reference. Qpr is evaluated from Mie theory for small spherical particles with measured optical properties, irradiated by the actual solar spectrum. Of the eight materials studied, only for iron, magnetite, and graphite grains does the radiation pressure force exceed gravity and then just for sizes around 0. -

Orbit Determination Using Modern Filters/Smoothers and Continuous Thrust Modeling

Orbit Determination Using Modern Filters/Smoothers and Continuous Thrust Modeling by Zachary James Folcik B.S. Computer Science Michigan Technological University, 2000 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF AERONAUTICS AND ASTRONAUTICS IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN AERONAUTICS AND ASTRONAUTICS AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2008 © 2008 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. Signature of Author:_______________________________________________________ Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics May 23, 2008 Certified by:_____________________________________________________________ Dr. Paul J. Cefola Lecturer, Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics Thesis Supervisor Certified by:_____________________________________________________________ Professor Jonathan P. How Professor, Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics Thesis Advisor Accepted by:_____________________________________________________________ Professor David L. Darmofal Associate Department Head Chair, Committee on Graduate Students 1 [This page intentionally left blank.] 2 Orbit Determination Using Modern Filters/Smoothers and Continuous Thrust Modeling by Zachary James Folcik Submitted to the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics on May 23, 2008 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Aeronautics and Astronautics ABSTRACT The development of electric propulsion technology for spacecraft has led to reduced costs and longer lifespans for certain -

Rideshare and the Orbital Maneuvering Vehicle: the Key to Low-Cost Lagrange-Point Missions

SSC15-II-5 Rideshare and the Orbital Maneuvering Vehicle: the Key to Low-cost Lagrange-point Missions Chris Pearson, Marissa Stender, Christopher Loghry, Joe Maly, Valentin Ivanitski Moog Integrated Systems 1113 Washington Avenue, Suite 300, Golden, CO, 80401; 303 216 9777, extension 204 [email protected] Mina Cappuccio, Darin Foreman, Ken Galal, David Mauro NASA Ames Research Center PO Box 1000, M/S 213-4, Moffett Field, CA 94035-1000; 650 604 1313 [email protected] Keats Wilkie, Paul Speth, Trevor Jackson, Will Scott NASA Langley Research Center 4 West Taylor Street, Mail Stop 230, Hampton, VA, 23681; 757 864 420 [email protected] ABSTRACT Rideshare is a well proven approach, in both LEO and GEO, enabling low-cost space access through splitting of launch charges between multiple passengers. Demand exists from users to operate payloads at Lagrange points, but a lack of regular rides results in a deficiency in rideshare opportunities. As a result, such mission architectures currently rely on a costly dedicated launch. NASA and Moog have jointly studied the technical feasibility, risk and cost of using an Orbital Maneuvering Vehicle (OMV) to offer Lagrange point rideshare opportunities. This OMV would be launched as a secondary passenger on a commercial rocket into Geostationary Transfer Orbit (GTO) and utilize the Moog ESPA secondary launch adapter. The OMV is effectively a free flying spacecraft comprising a full suite of avionics and a propulsion system capable of performing GTO to Lagrange point transfer via a weak stability boundary orbit. In addition to traditional OMV ’tug’ functionality, scenarios using the OMV to host payloads for operation at the Lagrange points have also been analyzed. -

Section 22-3: Energy, Momentum and Radiation Pressure

Answer to Essential Question 22.2: (a) To find the wavelength, we can combine the equation with the fact that the speed of light in air is 3.00 " 108 m/s. Thus, a frequency of 1 " 1018 Hz corresponds to a wavelength of 3 " 10-10 m, while a frequency of 90.9 MHz corresponds to a wavelength of 3.30 m. (b) Using Equation 22.2, with c = 3.00 " 108 m/s, gives an amplitude of . 22-3 Energy, Momentum and Radiation Pressure All waves carry energy, and electromagnetic waves are no exception. We often characterize the energy carried by a wave in terms of its intensity, which is the power per unit area. At a particular point in space that the wave is moving past, the intensity varies as the electric and magnetic fields at the point oscillate. It is generally most useful to focus on the average intensity, which is given by: . (Eq. 22.3: The average intensity in an EM wave) Note that Equations 22.2 and 22.3 can be combined, so the average intensity can be calculated using only the amplitude of the electric field or only the amplitude of the magnetic field. Momentum and radiation pressure As we will discuss later in the book, there is no mass associated with light, or with any EM wave. Despite this, an electromagnetic wave carries momentum. The momentum of an EM wave is the energy carried by the wave divided by the speed of light. If an EM wave is absorbed by an object, or it reflects from an object, the wave will transfer momentum to the object. -

Analysis of Interplanetary Transfers Between the Earth and Mars Halo Orbits

Analysis of Interplanetary Transfers between the Earth and Mars Halo orbits M. Nakamiya (1), H. Yamakawa (2), D. J. Scheeres (3) and M. Yoshikawa (4) (1) Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, 3-1-1 Sagamihara, Kanagawa 229-8510, Japan. nakamiya,[email protected] (2) University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado 80309, USA. [email protected] (3) KyotoUniversity, Gokasho, Uji, Kyoto 611-0011, Japan. [email protected] (4) Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, 3-1-1 Sagamihara, Kanagawa 229-8510, Japan. [email protected] Spacecraft interplanetary transportation systems using Earth and Mars Halo orbits are analyzed. This application is motivated by future proposals to place “deep space ports” at the Earth and Mars Halo orbits as space hub for planetary Mission. First, the feasibility of interplanetary trajectories between Earth Halo orbit and Mars Halo orbit was investigated, and such trajectories were designed with reasonable DV and flight time. Here, we utilize unstable and stable manifolds associated with the Halo orbit to approach the vicinity of the planet’s surface, and assume impulsive maneuver for escape and capture trajectories from/to Halo Orbits. Next, applying to Earth-Mars transportation system using spaceports on Halo orbits, we evaluated the system with respect to the mass of round-trip transfer. As a result, the transfer between the low Earth orbit and the low Mars orbit via the Earth Halo orbit and the Mars Halo orbit could be saved the fuel cost compared with a direct transfer between the low Earth orbit and the low Mars orbit 1. INTRODUCTION These days there has been great interest in the libration points of the circular restricted 3-body problem (CR3BP), where the gravity of the primary and secondary bodies and centrifugal force are balanced.