Statistical Orbit Determination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Low Thrust Manoeuvres to Perform Large Changes of RAAN Or Inclination in LEO

Facoltà di Ingegneria Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Ingegneria Aerospaziale Master Thesis Low Thrust Manoeuvres To Perform Large Changes of RAAN or Inclination in LEO Academic Tutor: Prof. Lorenzo CASALINO Candidate: Filippo GRISOT July 2018 “It is possible for ordinary people to choose to be extraordinary” E. Musk ii Filippo Grisot – Master Thesis iii Filippo Grisot – Master Thesis Acknowledgments I would like to address my sincere acknowledgments to my professor Lorenzo Casalino, for your huge help in these moths, for your willingness, for your professionalism and for your kindness. It was very stimulating, as well as fun, working with you. I would like to thank all my course-mates, for the time spent together inside and outside the “Poli”, for the help in passing the exams, for the fun and the desperation we shared throughout these years. I would like to especially express my gratitude to Emanuele, Gianluca, Giulia, Lorenzo and Fabio who, more than everyone, had to bear with me. I would like to also thank all my extra-Poli friends, especially Alberto, for your support and the long talks throughout these years, Zach, for being so close although the great distance between us, Bea’s family, for all the Sundays and summers spent together, and my soccer team Belfiga FC, for being the crazy lovable people you are. A huge acknowledgment needs to be address to my family: to my grandfather Luciano, for being a great friend; to my grandmother Bianca, for teaching me what “fighting” means; to my grandparents Beppe and Etta, for protecting me -

Osculating Orbit Elements and the Perturbed Kepler Problem

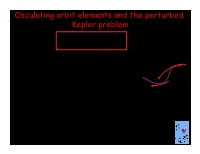

Osculating orbit elements and the perturbed Kepler problem Gmr a = 3 + f(r, v,t) Same − r x & v Define: r := rn ,r:= p/(1 + e cos f) ,p= a(1 e2) − osculating orbit he sin f h v := n + λ ,h:= Gmp p r n := cos ⌦cos(! + f) cos ◆ sinp ⌦sin(! + f) e − X +⇥ sin⌦cos(! + f) + cos ◆ cos ⌦sin(! + f⇤) eY actual orbit +sin⇥ ◆ sin(! + f) eZ ⇤ λ := cos ⌦sin(! + f) cos ◆ sin⌦cos(! + f) e − − X new osculating + sin ⌦sin(! + f) + cos ◆ cos ⌦cos(! + f) e orbit ⇥ − ⇤ Y +sin⇥ ◆ cos(! + f) eZ ⇤ hˆ := n λ =sin◆ sin ⌦ e sin ◆ cos ⌦ e + cos ◆ e ⇥ X − Y Z e, a, ω, Ω, i, T may be functions of time Perturbed Kepler problem Gmr a = + f(r, v,t) − r3 dh h = r v = = r f ⇥ ) dt ⇥ v h dA A = ⇥ n = Gm = f h + v (r f) Gm − ) dt ⇥ ⇥ ⇥ Decompose: f = n + λ + hˆ R S W dh = r λ + r hˆ dt − W S dA Gm =2h n h + rr˙ λ rr˙ hˆ. dt S − R S − W Example: h˙ = r S d (h cos ◆)=h˙ e dt · Z d◆ h˙ cos ◆ h sin ◆ = r cos(! + f)sin◆ + r cos ◆ − dt − W S Perturbed Kepler problem “Lagrange planetary equations” dp p3 1 =2 , dt rGm 1+e cos f S de p 2 cos f + e(1 + cos2 f) = sin f + , dt Gm R 1+e cos f S r d◆ p cos(! + f) = , dt Gm 1+e cos f W r d⌦ p sin(! + f) sin ◆ = , dt Gm 1+e cos f W r d! 1 p 2+e cos f sin(! + f) = cos f + sin f e cot ◆ dt e Gm − R 1+e cos f S− 1+e cos f W r An alternative pericenter angle: $ := ! +⌦cos ◆ d$ 1 p 2+e cos f = cos f + sin f dt e Gm − R 1+e cos f S r Perturbed Kepler problem Comments: § these six 1st-order ODEs are exactly equivalent to the original three 2nd-order ODEs § if f = 0, the orbit elements are constants § if f << Gm/r2, use perturbation theory -

Astrodynamics

Politecnico di Torino SEEDS SpacE Exploration and Development Systems Astrodynamics II Edition 2006 - 07 - Ver. 2.0.1 Author: Guido Colasurdo Dipartimento di Energetica Teacher: Giulio Avanzini Dipartimento di Ingegneria Aeronautica e Spaziale e-mail: [email protected] Contents 1 Two–Body Orbital Mechanics 1 1.1 BirthofAstrodynamics: Kepler’sLaws. ......... 1 1.2 Newton’sLawsofMotion ............................ ... 2 1.3 Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation . ......... 3 1.4 The n–BodyProblem ................................. 4 1.5 Equation of Motion in the Two-Body Problem . ....... 5 1.6 PotentialEnergy ................................. ... 6 1.7 ConstantsoftheMotion . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .... 7 1.8 TrajectoryEquation .............................. .... 8 1.9 ConicSections ................................... 8 1.10 Relating Energy and Semi-major Axis . ........ 9 2 Two-Dimensional Analysis of Motion 11 2.1 ReferenceFrames................................. 11 2.2 Velocity and acceleration components . ......... 12 2.3 First-Order Scalar Equations of Motion . ......... 12 2.4 PerifocalReferenceFrame . ...... 13 2.5 FlightPathAngle ................................. 14 2.6 EllipticalOrbits................................ ..... 15 2.6.1 Geometry of an Elliptical Orbit . ..... 15 2.6.2 Period of an Elliptical Orbit . ..... 16 2.7 Time–of–Flight on the Elliptical Orbit . .......... 16 2.8 Extensiontohyperbolaandparabola. ........ 18 2.9 Circular and Escape Velocity, Hyperbolic Excess Speed . .............. 18 2.10 CosmicVelocities -

Orbit Determination Methods and Techniques

PROJECTE FINAL DE CARRERA (PFC) GEOSAR Mission: Orbit Determination Methods and Techniques Marc Fernàndez Uson PFC Advisor: Prof. Antoni Broquetas Ibars May 2016 PROJECTE FINAL DE CARRERA (PFC) GEOSAR Mission: Orbit Determination Methods and Techniques Marc Fernàndez Uson ABSTRACT ABSTRACT Multiple applications such as land stability control, natural risks prevention or accurate numerical weather prediction models from water vapour atmospheric mapping would substantially benefit from permanent radar monitoring given their fast evolution is not observable with present Low Earth Orbit based systems. In order to overcome this drawback, GEOstationary Synthetic Aperture Radar missions (GEOSAR) are presently being studied. GEOSAR missions are based on operating a radar payload hosted by a communication satellite in a geostationary orbit. Due to orbital perturbations, the satellite does not follow a perfectly circular orbit, but has a slight eccentricity and inclination that can be used to form the synthetic aperture required to obtain images. Several sources affect the along-track phase history in GEOSAR missions causing unwanted fluctuations which may result in image defocusing. The main expected contributors to azimuth phase noise are orbit determination errors, radar carrier frequency drifts, the Atmospheric Phase Screen (APS), and satellite attitude instabilities and structural vibration. In order to obtain an accurate image of the scene after SAR processing, the range history of every point of the scene must be known. This fact requires a high precision orbit modeling and the use of suitable techniques for atmospheric phase screen compensation, which are well beyond the usual orbit determination requirement of satellites in GEO orbits. The other influencing factors like oscillator drift and attitude instability, vibration, etc., must be controlled or compensated. -

Orbit Options for an Orion-Class Spacecraft Mission to a Near-Earth Object

Orbit Options for an Orion-Class Spacecraft Mission to a Near-Earth Object by Nathan C. Shupe B.A., Swarthmore College, 2005 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Aerospace Engineering Sciences 2010 This thesis entitled: Orbit Options for an Orion-Class Spacecraft Mission to a Near-Earth Object written by Nathan C. Shupe has been approved for the Department of Aerospace Engineering Sciences Daniel Scheeres Prof. George Born Assoc. Prof. Hanspeter Schaub Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Shupe, Nathan C. (M.S., Aerospace Engineering Sciences) Orbit Options for an Orion-Class Spacecraft Mission to a Near-Earth Object Thesis directed by Prof. Daniel Scheeres Based on the recommendations of the Augustine Commission, President Obama has pro- posed a vision for U.S. human spaceflight in the post-Shuttle era which includes a manned mission to a Near-Earth Object (NEO). A 2006-2007 study commissioned by the Constellation Program Advanced Projects Office investigated the feasibility of sending a crewed Orion spacecraft to a NEO using different combinations of elements from the latest launch system architecture at that time. The study found a number of suitable mission targets in the database of known NEOs, and pre- dicted that the number of candidate NEOs will continue to increase as more advanced observatories come online and execute more detailed surveys of the NEO population. -

Orbit Determination Using Modern Filters/Smoothers and Continuous Thrust Modeling

Orbit Determination Using Modern Filters/Smoothers and Continuous Thrust Modeling by Zachary James Folcik B.S. Computer Science Michigan Technological University, 2000 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF AERONAUTICS AND ASTRONAUTICS IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN AERONAUTICS AND ASTRONAUTICS AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2008 © 2008 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. Signature of Author:_______________________________________________________ Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics May 23, 2008 Certified by:_____________________________________________________________ Dr. Paul J. Cefola Lecturer, Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics Thesis Supervisor Certified by:_____________________________________________________________ Professor Jonathan P. How Professor, Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics Thesis Advisor Accepted by:_____________________________________________________________ Professor David L. Darmofal Associate Department Head Chair, Committee on Graduate Students 1 [This page intentionally left blank.] 2 Orbit Determination Using Modern Filters/Smoothers and Continuous Thrust Modeling by Zachary James Folcik Submitted to the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics on May 23, 2008 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Aeronautics and Astronautics ABSTRACT The development of electric propulsion technology for spacecraft has led to reduced costs and longer lifespans for certain -

Assessment of Earth Gravity Field Models in the Medium to High Frequency Spectrum Based on GRACE and GOCE Dynamic Orbit Analysis

Article Assessment of Earth Gravity Field Models in the Medium to High Frequency Spectrum Based on GRACE and GOCE Dynamic Orbit Analysis Thomas D. Papanikolaou 1,2,* and Dimitrios Tsoulis 3 1 Geoscience Australia, Cnr Jerrabomberra Ave and Hindmarsh Drive, Symonston, ACT 2609, Australia 2 Cooperative Research Centre for Spatial Information, Docklands, VIC 3008, Australia 3 Department of Geodesy and Surveying, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 54124 Thessaloniki, Greece; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 22 October 2018; Accepted: 23 November 2018; Published: 27 November 2018 Abstract: An analysis of current static and time-variable gravity field models is presented focusing on the medium to high frequencies of the geopotential as expressed by the spherical harmonic coefficients. A validation scheme of the gravity field models is implemented based on dynamic orbit determination that is applied in a degree-wise cumulative sense of the individual spherical harmonics. The approach is applied to real data of the Gravity Field and Steady-State Ocean Circulation (GOCE) and Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellite missions, as well as to GRACE inter-satellite K-band ranging (KBR) data. Since the proposed scheme aims at capturing gravitational discrepancies, we consider a few deterministic empirical parameters in order to avoid absorbing part of the gravity signal that may be included in the monitored orbit residuals. The present contribution aims at a band-limited analysis for identifying characteristic degree ranges and thresholds of the various GRACE- and GOCE-based gravity field models. The degree range 100–180 is investigated based on the degree-wise cumulative approach. -

The Evolution of Earth Gravitational Models Used in Astrodynamics

JEROME R. VETTER THE EVOLUTION OF EARTH GRAVITATIONAL MODELS USED IN ASTRODYNAMICS Earth gravitational models derived from the earliest ground-based tracking systems used for Sputnik and the Transit Navy Navigation Satellite System have evolved to models that use data from the Joint United States-French Ocean Topography Experiment Satellite (Topex/Poseidon) and the Global Positioning System of satellites. This article summarizes the history of the tracking and instrumentation systems used, discusses the limitations and constraints of these systems, and reviews past and current techniques for estimating gravity and processing large batches of diverse data types. Current models continue to be improved; the latest model improvements and plans for future systems are discussed. Contemporary gravitational models used within the astrodynamics community are described, and their performance is compared numerically. The use of these models for solid Earth geophysics, space geophysics, oceanography, geology, and related Earth science disciplines becomes particularly attractive as the statistical confidence of the models improves and as the models are validated over certain spatial resolutions of the geodetic spectrum. INTRODUCTION Before the development of satellite technology, the Earth orbit. Of these, five were still orbiting the Earth techniques used to observe the Earth's gravitational field when the satellites of the Transit Navy Navigational Sat were restricted to terrestrial gravimetry. Measurements of ellite System (NNSS) were launched starting in 1960. The gravity were adequate only over sparse areas of the Sputniks were all launched into near-critical orbit incli world. Moreover, because gravity profiles over the nations of about 65°. (The critical inclination is defined oceans were inadequate, the gravity field could not be as that inclination, 1= 63 °26', where gravitational pertur meaningfully estimated. -

Orbit Conjunction Filters Final

AAS 09-372 A DESCRIPTION OF FILTERS FOR MINIMIZING THE TIME REQUIRED FOR ORBITAL CONJUNCTION COMPUTATIONS James Woodburn*, Vincent Coppola† and Frank Stoner‡ Classical filters used in the identification of orbital conjunctions are described and examined for potential failure cases. Alternative implementations of the filters are described which maintain the spirit of the original concepts but improve robustness. The computational advantage provided by each filter when applied to the one versus all and the all versus all orbital conjunction problems are presented. All of the classic filters are shown to be applicable to conjunction detection based on tabulated ephemerides in addition to two line element sets. INTRODUCTION The problem of on-orbit collisions or near collisions is receiving increased attention in light of the recent collision between an Iridium satellite and COSMOS 2251. More recently, the crew of the International Space Station was evacuated to the Soyuz module until a chunk of debris had safely passed. Dealing with the reality of an ever more crowded space environment requires the identification of potentially dangerous orbital conjunctions followed by the selection of an appropriate course of action. This text serves to describe the process of identifying all potential orbital conjunctions, or more specifically, the techniques used to allow the computations to be performed reliably and within a reasonable period of time. The identification of potentially dangerous conjunctions is most commonly done by determining periods of time when two objects have an unacceptable risk of collision. For this analysis, we will use the distance between the objects as our proxy for risk of collision. -

Draft American National Standard Astrodynamics

BSR/AIAA S-131-200X Draft American National Standard Astrodynamics – Propagation Specifications, Test Cases, and Recommended Practices Warning This document is not an approved AIAA Standard. It is distributed for review and comment. It is subject to change without notice. Recipients of this draft are invited to submit, with their comments, notification of any relevant patent rights of which they are aware and to provide supporting documentation. Sponsored by American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Approved XX Month 200X American National Standards Institute Abstract This document provides the broad astrodynamics and space operations community with technical standards and lays out recommended approaches to ensure compatibility between organizations. Applicable existing standards and accepted documents are leveraged to make a complete—yet coherent—document. These standards are intended to be used as guidance and recommended practices for astrodynamics applications in Earth orbit where interoperability and consistency of results is a priority. For those users who are purely engaged in research activities, these standards can provide an accepted baseline for innovation. BSR/AIAA S-131-200X LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING DATA WILL BE ADDED HERE BY AIAA STAFF Published by American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics 1801 Alexander Bell Drive, Reston, VA 20191 Copyright © 200X American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form, in an electronic retrieval -

The Joint Gravity Model 3

Journal of Geophysical Research Accepted for publication, 1996 The Joint Gravity Model 3 B. D. Tapley, M. M. Watkins,1 J. C. Ries, G. W. Davis,2 R. J. Eanes, S. R. Poole, H. J. Rim, B. E. Schutz, and C. K. Shum Center for Space Research, University of Texas at Austin R. S. Nerem,3 F. J. Lerch, and J. A. Marshall Space Geodesy Branch, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland S. M. Klosko, N. K. Pavlis, and R. G. Williamson Hughes STX Corporation, Lanham, Maryland Abstract. An improved Earth geopotential model, complete to spherical harmonic degree and order 70, has been determined by combining the Joint Gravity Model 1 (JGM 1) geopotential coef®cients, and their associated error covariance, with new information from SLR, DORIS, and GPS tracking of TOPEX/Poseidon, laser tracking of LAGEOS 1, LAGEOS 2, and Stella, and additional DORIS tracking of SPOT 2. The resulting ®eld, JGM 3, which has been adopted for the TOPEX/Poseidon altimeter data rerelease, yields improved orbit accuracies as demonstrated by better ®ts to withheld tracking data and substantially reduced geographically correlated orbit error. Methods for analyzing the performance of the gravity ®eld using high-precision tracking station positioning were applied. Geodetic results, including station coordinates and Earth orientation parameters, are signi®cantly improved with the JGM 3 model. Sea surface topography solutions from TOPEX/Poseidon altimetry indicate that the ocean geoid has been improved. Subset solutions performed by withholding either the GPS data or the SLR/DORIS data were computed to demonstrate the effect of these particular data sets on the gravity model used for TOPEX/Poseidon orbit determination. -

Satellite Orbits

Course Notes for Ocean Colour Remote Sensing Course Erdemli, Turkey September 11 - 22, 2000 Module 1: Satellite Orbits prepared by Assoc Professor Mervyn J Lynch Remote Sensing and Satellite Research Group School of Applied Science Curtin University of Technology PO Box U1987 Perth Western Australia 6845 AUSTRALIA tel +618-9266-7540 fax +618-9266-2377 email <[email protected]> Module 1: Satellite Orbits 1.0 Artificial Earth Orbiting Satellites The early research on orbital mechanics arose through the efforts of people such as Tyco Brahe, Copernicus, Kepler and Galileo who were clearly concerned with some of the fundamental questions about the motions of celestial objects. Their efforts led to the establishment by Keppler of the three laws of planetary motion and these, in turn, prepared the foundation for the work of Isaac Newton who formulated the Universal Law of Gravitation in 1666: namely, that F = GmM/r2 , (1) Where F = attractive force (N), r = distance separating the two masses (m), M = a mass (kg), m = a second mass (kg), G = gravitational constant. It was in the very next year, namely 1667, that Newton raised the possibility of artificial Earth orbiting satellites. A further 300 years lapsed until 1957 when the USSR achieved the first launch into earth orbit of an artificial satellite - Sputnik - occurred. Returning to Newton's equation (1), it would predict correctly (relativity aside) the motion of an artificial Earth satellite if the Earth was a perfect sphere of uniform density, there was no atmosphere or ocean or other external perturbing forces. However, in practice the situation is more complicated and prediction is a less precise science because not all the effects of relevance are accurately known or predictable.