Chinese, Tibetan and Mongol Buddhists on Mount Wutai (China) from the Eighteenth to the Twenty-First Century Isabelle Charleux

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gurudharmas in Buddhist Nunneries of Mainland China

BSRV 31.2 (2014) 241–272 Buddhist Studies Review ISSN (print) 0256-2897 doi: 10.1558/bsrv.v31i2.241 Buddhist Studies Review ISSN (online) 1747-9681 The Gurudharmas in Buddhist Nunneries of Mainland China TZU-LUNG CHIU AND ANN HEIRMAN DEPARTMENT OF CHINESE LANGUAGE AND CULTURE, FACULTY OF ARTS AND PHILOSOPHY, GHENT UNIVERSITY [email protected]; [email protected] ABSTRACT According to tradition, when the Buddha’s aunt and stepmother Mahāprajāpatī was allowed to join the Buddhist monastic com- munity, she accepted eight ‘fundamental rules’ (gurudharmas) that made the nuns’ order dependent upon the monks’ order. This story has given rise to much debate, in the past as well as in the present, and this is no less the case in Mainland China, where nunneries have started to re-emerge in recent decades. This article first presents new insight into Mainland Chinese monastic practitioners’ common perspectives and voices regarding the gurudharmas, which are rarely touched upon in scholarly work. Next, each of the rules is discussed in detail, allowing us to analyse various issues, until now under- studied, regarding the applicability of the gurudharmas in Mainland Chinese contexts. This research thus provides a detailed overview of nuns’ perceptions of how traditional vinaya rules and procedures can be applied in contemporary Mainland Chinese monastic com- munities based on a cross-regional empirical study. Keywords Mainland Chinese nuns, gurudharma, vinaya, gender Introduction The accounts on the founding of the Buddhist order of nuns (bhikṣuṇīsaṅgha) explain in detail how, around two and a half millennia ago, the bhikṣuṇīsaṅgha was established when the Buddha allowed women to join the Buddhist monastic community. -

RET HS No. 1:RET Hors Série No. 1

Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines Table des Matières récapitulative des nos. 1-15 Hors-série numéro 01 — Août 2009 Table des Matières récapitulative des numéros 1-15 Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines Hors-série no. 1 — Août 2009 ISSN 1768-2959 Directeur : Jean-Luc Achard Comité de rédaction : Anne Chayet, Pierre Arènes, Jean-Luc Achard. Comité de lecture : Pierre Arènes (CNRS), Ester Bianchi (Dipartimento di Studi sull’Asia Orientale, Venezia), Anne Chayet (CNRS), Fabienne Jagou (EFEO), Rob Mayer (Oriental Institute, University of Oxford), Fernand Meyer (CNRS-EPHE), Fran- çoise Pommaret (CNRS), Ramon Prats (Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona), Brigitte Steinman (Université de Lille) Jean-Luc Achard (CNRS). Périodicité La périodicité de la Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines est généralement bi-annuelle, les mois de parution étant, sauf indication contraire, Octobre et Avril. Les contributions doivent parvenir au moins deux (2) mois à l’avance. Les dates de proposition d’articles au co- mité de lecture sont Février pour une parution en Avril et Août pour une parution en Octobre. Participation La participation est ouverte aux membres statutaires des équipes CNRS, à leurs mem- bres associés, aux doctorants et aux chercheurs non-affiliés. Les articles et autres contributions sont proposées aux membres du comité de lec ture et sont soumis à l’approbation des membres du comité de rédaction. Les arti cles et autres contributions doivent être inédits ou leur ré-édition doit être justifiée et soumise à l’approbation des membres du comité de lecture. Les documents doivent parvenir sous la forme de fichiers Word (.doc exclusive- ment avec fontes unicodes), envoyés à l’adresse du directeur ([email protected]). -

Tibeto-Mongol and Chinese Buddhism in Present-Day Hohhot, Inner Mongolia: Competition and Interactions Isabelle Charleux

Tibeto-Mongol and Chinese Buddhism in Present-day Hohhot, Inner Mongolia: Competition and Interactions Isabelle Charleux To cite this version: Isabelle Charleux. Tibeto-Mongol and Chinese Buddhism in Present-day Hohhot, Inner Mongolia: Competition and Interactions. Sino-Tibetan Buddhism across the Ages, 5, 2021, Studies on East Asian Religions. halshs-03327320 HAL Id: halshs-03327320 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03327320 Submitted on 27 Aug 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Isabelle Charleux. Authors’ own file, not the published version in Sino-Tibetan Buddhism across the Ages, Ester Bianchi & Shen Weirong (dir.), Brill : Leyde & Boston (Studies on East Asian Religious, vol. 5), 2021 Tibeto-Mongol and Chinese Buddhism in Present-day Hohhot, Inner Mongolia: Competition and Interactions Isabelle Charleux* Abstract This chapter investigates the architecture, icons, and activities of two Buddhist monasteries of the Old City of Hohhot, capital of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region of China: the (Tibeto-)Mongol Yeke juu (Ch. Dazhao[si]) and the Chinese Buddhist Guanyinsi. In it, I present a global view of the Buddhist revival of the Mongol monasteries of Hohhot since the 1980s, with a focus on the material culture—architecture, cult objects, and “decoration”—of the sites. -

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia. A bibliography of historical and modern texts with introduction and partial annotation, and some echoes in Western countries. [This annotated bibliography of 220 items suggests the range and major themes of how Buddhism and people influenced by Buddhism have responded to disability in Asia through two millennia, with cultural background. Titles of the materials may be skimmed through in an hour, or the titles and annotations read in a day. The works listed might take half a year to find and read.] M. Miles (compiler and annotator) West Midlands, UK. November 2013 Available at: http://www.independentliving.org/miles2014a and http://cirrie.buffalo.edu/bibliography/buddhism/index.php Some terms used in this bibliography Buddhist terms and people. Buddhism, Bouddhisme, Buddhismus, suffering, compassion, caring response, loving kindness, dharma, dukkha, evil, heaven, hell, ignorance, impermanence, kamma, karma, karuna, metta, noble truths, eightfold path, rebirth, reincarnation, soul, spirit, spirituality, transcendent, self, attachment, clinging, delusion, grasping, buddha, bodhisatta, nirvana; bhikkhu, bhikksu, bhikkhuni, samgha, sangha, monastery, refuge, sutra, sutta, bonze, friar, biwa hoshi, priest, monk, nun, alms, begging; healing, therapy, mindfulness, meditation, Gautama, Gotama, Maitreya, Shakyamuni, Siddhartha, Tathagata, Amida, Amita, Amitabha, Atisha, Avalokiteshvara, Guanyin, Kannon, Kuan-yin, Kukai, Samantabhadra, Santideva, Asoka, Bhaddiya, Khujjuttara, -

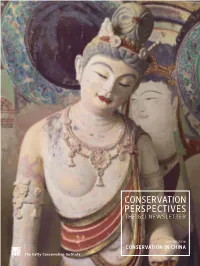

Conservation in China Issue, Spring 2016

SPRING 2016 CONSERVATION IN CHINA A Note from the Director For over twenty-five years, it has been the Getty Conservation Institute’s great privilege to work with colleagues in China engaged in the conservation of cultural heritage. During this quarter century and more of professional engagement, China has undergone tremendous changes in its social, economic, and cultural life—changes that have included significant advance- ments in the conservation field. In this period of transformation, many Chinese cultural heritage institutions and organizations have striven to establish clear priorities and to engage in significant projects designed to further conservation and management of their nation’s extraordinary cultural resources. We at the GCI have admiration and respect for both the progress and the vision represented in these efforts and are grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage in China. The contents of this edition of Conservation Perspectives are a reflection of our activities in China and of the evolution of policies and methods in the work of Chinese conservation professionals and organizations. The feature article offers Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI a concise view of GCI involvement in several long-term conservation projects in China. Authored by Neville Agnew, Martha Demas, and Lorinda Wong— members of the Institute’s China team—the article describes Institute work at sites across the country, including the Imperial Mountain Resort at Chengde, the Yungang Grottoes, and, most extensively, the Mogao Grottoes. Integrated with much of this work has been our participation in the development of the China Principles, a set of national guide- lines for cultural heritage conservation and management that respect and reflect Chinese traditions and approaches to conservation. -

Meeting of Minds.Pdf

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Translation:Wang Ming Yee Geshe Thubten Jinpa, and Guo-gu Editing:Lindley Hanlon Ernest Heau Editorial Assistance:Guo-gu Alex Wang John Anello Production: Guo-gu Cover Design:Guo-gu Chih-ching Lee Cover Photos:Guo-gu Kevin Hsieh Photos in the book:Kevin Hsieh Dharma Drum Mountain gratefully acknowledges all those who generously contributed to the publication and distribution of this book. CONTENTS Foreword Notes to the Reader 08 A Brief Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism By His Holiness the 14 th Dalai Lama 22 A Dialogue on Tibetan and Chinese Buddhism His Holiness the 14 th Dalai Lama and Venerable Chan Master Sheng Yen 68 Glossary 83 Appendix About His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama About the Master Sheng Yen 2 Meeting of Minds Foreword n May 1st through the 3rd, 1998, His Holiness the O 14th Dalai Lama and Venerable Chan Master Sheng Yen presented In the Spirit of Manjushri: the Wisdom Teachings of Buddhism, at the Roseland in New York City. Tibet House New York and the Dharma Drum Mountain Buddhist Association sponsored the event, which drew some 2,500 people from all Buddhist traditions, as well as scholars of medicine, comparative religion, psychology, education, and comparative religion from around the world. It was a three-day discourse designed to promote understanding among Chinese, Tibetan, and Western Buddhists. His Holiness presented two-and-a-half days of teaching on Tibetan Buddhism. A dialogue with Venerable Master Sheng Yen, one of the foremost scholars and teachers of Chinese Chan (Zen) Buddhism, followed on the afternoon of the third day. -

US Pagans and Indigenous Americans: Land and Identity

religions Article US Pagans and Indigenous Americans: Land and Identity Lisa A. McLoughlin Independent Scholar, Northfield, MA 01360, USA; [email protected] Received: 2 January 2019; Accepted: 27 February 2019; Published: 1 March 2019 Abstract: In contrast to many European Pagan communities, ancestors and traditional cultural knowledge of Pagans in the United States of America (US Pagans) are rooted in places we no longer reside. Written from a US Pagan perspective, for an audience of Indigenous Americans, Pagans, and secondarily scholars of religion, this paper frames US Paganisms as bipartite with traditional and experiential knowledge; explores how being transplanted from ancestral homelands affects US Pagans’ relationship to the land we are on, to the Indigenous people of that land, and any contribution these may make to the larger discussion of indigeneity; and works to dispel common myths about US Pagans by offering examples of practices that the author suggests may be respectful to Indigenous American communities, while inviting Indigenous American comments on this assessment. Keywords: US Pagans; Indigenous Americans; identity; land; cultural appropriation; indigeneity 1. Introduction Indigenous American scholar Vine Deloria Jr. (Deloria 2003, pp. 292–93) contends: “That a fundamental element of religion is an intimate relationship with the land on which the religion is practiced should be a major premise of future theological concern.” Reading of Indigenous American and Pagan literatures1 indicates that both communities, beyond simply valuing their relationship with the land, consider it as part of their own identity. As for example, in this 1912 Indigenous American quote: “The soil you see is not ordinary soil—it is the dust of the blood, the flesh, and the bones of our ancestors. -

The Vows of the Four Great Bodhisattvas

The vows of the four great Bodhisattvas © Thich Nhat Hanh Dear Sangha, today is the 15th January and we are in the New Hamlet. Today we will be studying the vows of the four great Bodhisattvas contained in the chanting of Monday evening. Before we begin, I would like to make a few announcements. On the 4th of February we will be having an ordination ceremony for a number of new novice monks and nuns. That day will be a very nice day. In the early morning we will have the ordination ceremony…. I am now pregnant with these new babies and there is a lot of agitation in my womb because we are not yet sure how many babies I will give birth to. It seems that there are three, there may be four… it is uncertain right now. On the same day, after lunch we will have the ceremony of Lamp Transmission (ordaining a new Dharma Teacher). There is only one nun (the Abbess) from the New Hamlet receiving the Lamp on that day so she will be able to give a long talk. I think that she will be giving a wonderful talk. She may tell us what led her to become a nun, what difficulties has she faced and how she has overcome them. She has been a nun for 24 or 25 years, since she was very young, and she has changed temples and practice centers a lot. Finally she has come to dwell with us here in our practice center, and so I am sure that she will have a lot to share with you. -

Chinese Architecture China Has Maintained the Highest Degree of Cultural Continuity Across Its 4000 Years of Existence

Chinese Architecture China has maintained the highest degree of cultural continuity across its 4000 years of existence. Its architectural traditions were very stable until the 19th c. China’s strong central authority is reflected in the Great Wall and standard dimensions for construction. Since the Tang Dynasty (7th-10th c.), Chinese architecture has had a major influence on the architectural styles of Korea, Vietnam, and Japan. Neolithic Houses at Banpo, ca 2000 BCE These dwellings used readily available materials—wood, thatch, and earth— to provide shelter. A central hearth is also part of many houses. The rectangular houses were sunk a half story into the ground. The Great Wall of China, 221 BCE-1368 CE. 19-39’ in height and 16’ wide. Almost 4000 miles long. Begun in pieces by feudal lords, unified by the first Qin emperor and largely rebuilt and extended during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 CE) Originally the great wall was made with rammed earth but during the Ming Dynasty its height was raised and it was cased with bricks or stones. https://youtu.be/o9rSlYxJIIE 1;05 Deified Lao Tzu. 8th - 11th c. Taoism or Daoism is a Chinese mystical philosophy traditionally founded by Lao-tzu in the sixth century BCE. It seeks harmony of human action and the world through study of nature. It tends to emphasize effortless Garden of the Master of the action, "naturalness", simplicity Fishing Nets in Suzhou, 1140. and spontaneity. Renovated in 1785 Life is a series of natural and spontaneous changes. Don’t resist them – that only creates sorrow. -

The Spreading of Christianity and the Introduction of Modern Architecture in Shannxi, China (1840-1949)

Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid Programa de doctorado en Concervación y Restauración del Patrimonio Architectónico The Spreading of Christianity and the introduction of Modern Architecture in Shannxi, China (1840-1949) Christian churches and traditional Chinese architecture Author: Shan HUANG (Architect) Director: Antonio LOPERA (Doctor, Arquitecto) 2014 Tribunal nombrado por el Magfco. y Excmo. Sr. Rector de la Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, el día de de 20 . Presidente: Vocal: Vocal: Vocal: Secretario: Suplente: Suplente: Realizado el acto de defensa y lectura de la Tesis el día de de 20 en la Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid. Calificación:………………………………. El PRESIDENTE LOS VOCALES EL SECRETARIO Index Index Abstract Resumen Introduction General Background........................................................................................... 1 A) Definition of the Concepts ................................................................ 3 B) Research Background........................................................................ 4 C) Significance and Objects of the Study .......................................... 6 D) Research Methodology ...................................................................... 8 CHAPTER 1 Introduction to Chinese traditional architecture 1.1 The concept of traditional Chinese architecture ......................... 13 1.2 Main characteristics of the traditional Chinese architecture .... 14 1.2.1 Wood was used as the main construction materials ........ 14 1.2.2 -

Download Mountains.Pdf

MOUNTAINS AND THE SACRED Mountains loom large in any landscape and have long been invested with sacredness by many peoples around the world. They carry a rich symbolism. The vertical axis of the mountain drawn from its peak down to its base links it with the world-axis, and, as in the case of the Cosmic Tree (cf. Trees and the Sacred), is identified as the centre of the world. This belief is attached, for example, to Mount Tabor of the Israelites and Mount Meru of the Hindus. Besides natural mountains being invested with the sacred, there are numerous examples of mountains being built, such as the Mesopotamia ziggurats, the pyramids in Egypt [cf. Giza Plateau, Egypt], the pre- Columbian teocallis, and the temple-mountain of Borobudur. In most cases, the tops of real and artificial mountains are the locations for sanctuaries, shrines, or altars. In Ancient Greece the pre-eminent god of the mountain was Zeus for whom there existed nearly one hundred mountain cults. Zeus, who was born and brought up on a mountain (he was allegedly born in a cave [cf. The Sacred Cave] on Mount Ida on Crete), and who ruled supreme on Mount Olympus, was a god of rain and lightning (to Zeus as a god of rain is dedicated the sanctuary of Zeus Ombrios on Hymettos). Mountains figure a great deal in Greek mythology -- the Muses occupy on Mount Helikon, Apollo is associated with Parnassos [cf. Delphi], and Athena with the Athenian Acropolis. In Japan, Mount Fuji (Fujiyama) is revered by Shintoists as sacred to the goddess Sengen-Sama, whose shrine is found at the summit. -

Out of the Shadows: Socially Engaged Buddhist Women

University of San Diego Digital USD Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship Department of Theology and Religious Studies 2019 Out of the Shadows: Socially Engaged Buddhist Women Karma Lekshe Tsomo PhD University of San Diego, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/thrs-faculty Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Digital USD Citation Tsomo, Karma Lekshe PhD, "Out of the Shadows: Socially Engaged Buddhist Women" (2019). Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship. 25. https://digital.sandiego.edu/thrs-faculty/25 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Theology and Religious Studies at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Section Titles Placed Here | I Out of the Shadows Socially Engaged Buddhist Women Edited by Karma Lekshe Tsomo SAKYADHITA | HONOLULU First Edition: Sri Satguru Publications 2006 Second Edition: Sakyadhita 2019 Copyright © 2019 Karma Lekshe Tsomo All rights reserved No part of this book may not be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage or retreival system, without the prior written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations. Cover design Copyright © 2006 Allen Wynar Sakyadhita Conference Poster