Creating the Dynamics of Hard-To-Imitate Innovation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Bulletin

TECHNICAL BULLETIN [Issue No.] T10-0028E [Page] 1/6 [Title] List of valid devices applicable for GOT900 series [Date of Issue] Oct., '05 [Relevant Models] GOT-A900 series Thank you for your continued support of Mitsubishi Graphic Operation Terminal GOT900 series. The peripheral devices listed in this bulletin have been concluded by Mitsubishi to be applicable for the GOT900 series. Compatible product A product that satisfies the requirements to be interfaced with Mitsubishi products. (Note that satisfaction of Mitsubishi specifications is not guaranteed.) Therefore, make sure to comply with the specifications for that product when using it together with Mitsubishi products. 1. Printers for GOT (compatible product) Cautions y Do not use the ESC/P raster-specific printer for the GOT. y Set hard copy function to "Monochrome" when using the GOT with a monochrome type printer. y When printing Chinese characters, use the printer that supports GB (simplified characters) or BIG5 (traditional) code, and includes the relevant fonts. Please refer to the applicable printer models below: Manufacturer Model LQ-2080C (BIG5-compatible) Seiko Epson Corporation LQ-1600K (GB-compatible) Oki Electric Industry Co., Ltd 5530SC (GB-compatible) Hewlett-Packard Development Company, L.P. HP LaserJet1150, HP LaserJet1300 2. PC cards for GOT "Compact Flash PC card" (compatible product) For GOTs compatible with compact flash PC cards, refer to the technical bulletin T10-0029 "Compatibility with commercially available flash PC cards". (Please note that some GOTs are incompatible with compact flash PC cards.) The GOT flash PC card (A9GTMEM-*MF) is applicable to A985GOT-V, A985GOT, A97*GOT and A960GOT. -

NOTICE of FISCAL YEAR 2018 (The 55Th FY) ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING of SHAREHOLDERS

㻝㻌 World Headquarters 3-1 Akasaka 5-chome, Minato-ku Tokyo 107-6325, Japan ISIN JP3571400005 Tel:+81-3-5561-7000 SEDOL 6895675 TSE 8035 May 28, 2018 NOTICE OF FISCAL YEAR 2018 (the 55th FY) ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING OF SHAREHOLDERS To Our Shareholders: We are pleased to announce that the 55th Annual General Meeting of Shareholders (the “AGM”) of Tokyo Electron Ltd. (“TEL”) will be held on Tuesday, June 19, 2018, at 10:00 a.m. Japan standard time, at PALACE HOTEL TOKYO, located at 1-1 Marunouchi 1-chome, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo. Shareholders will also be asked to vote upon the following Agenda: 1: Election of Twelve Corporate Directors 2: Payment of Bonuses to Corporate Directors for the 55th Fiscal Year 3: Issuance of Share Subscription Rights as Stock-Based Compensation to Corporate Directors 4: Issuance of Share Subscription Rights as Stock-Based Compensation to Executives of the Company and its Subsidiaries 5: Introduction of a Stock Compensation System as Medium-term Performance-linked Compensation for Corporate Directors of the Company As part of our ongoing effort to improve the quality of communications with our foreign investors and to increase the participation of those investors and to exercise your voting rights at the AGM, Tokyo Electron Ltd. has appointed IR Japan, Inc. as our Global Information Agent in connection with the shareholder meeting. We realize that many shareholders do not vote at Japanese Shareholders Meeting due to the volume of meetings and timing concerns. Therefore, we attach special importance to your vote, and hope that you will continue to distinguish yourselves from many institutions, who, unfortunately, do not participate. -

Mro & Key Engineered Solutions

KEY MRO & KEY ENGINEERED SOLUTIONS INDUSTRIES Japanese, Korean, and European Parts Importer Front View Side View Rear View Rear ISO View Front View Side View Rear View Rear ISO View Filter & Element Manufacturers Taisei Kogyo Masuda Ikura Seiki Maeda Hitachi Toyooki Yamashin Yuken Akamatsu Nippon Oil Amano Advantec Toyo Matsui Relay, Breaker, and Contactor Manufacturers Fuji Electric Omron Mitsubishi Electric Sentec Idec PLC Manufacturers Mitsubishi Omron Keyence Sharp Toei Denki Yas IAI Matsushita Shinpo Yaskawa Electric Switch Manufacturers Azbil/Yamatake Noken Fuji Electric Metrol Omron Seeka Keyence Sugiyama Mitsubishi Tamagawa Sanwa Denki Valcom Sunx NKK Idec Takigen Onno Sokki RKC Pneumatic Air Cylinders Manufacturers SMC CKD Taiyo Koganei NOK NKE New Era Nihon Seiki Coupling Manufacturers Bridgestone Oriental Tsubaki Miki Pulley Hasec Jatek Sanko Tamagawa Ogura JAC NBK Sakai Aluminum Extrusion Manufacturers Parco O-Ring and Seals Manufacturers NOK Sakagami Chain, Cable Carrier, Sprocket, and Gear Manufacturers CHAIN BELTS Tsubaki Mitsuboshi (Tohen) Ohmine Unitta Katayama Tsubaki Bando CABLE CARRIERS Kito Sling Tsubaki NOK Mirai Maruyasu Igus Seigling Hanshin SPROCKETS Tsubaki Kana Katayama Motor and Gear Box Manufacturers MOTORS GEAR BOX Mitsubishi Nissei Nissei Oriental Oriental Panasonic Toshiba Tsubaki Nikuaii Sumitomo Yaskawa Shimpo Hitachi Panasonic Taiyo Sumitomo Omron Pump Manufacturers Racine Tsurumi Ebara Nippon Pump Nikumi SR Engineering Pascal IHI Sumitomo Teral Iwata Nuchi Cube Ball Screws and LM Guides NSK THK IKO ASK Bearing Manufacturers NSK IKO SKF NTN Koyo EZO INA Nachi Mineba NMB Hydraulic Valve and Cylinder Manufacturers Daikin Yuken KCC Taco Kitz Tokimec Nachi Toyooki Showa Nakaseiki Horiuchi Tsubaki Riken Kosmek Electric Actuator Manufacturers IAI Yamaha SMC Sensor and Probe Manufacturers Azbil/Yamatake FCC Omron Keyence Sony Magnescale Kyowa Valcom Panasonic Hokuyo Takenaka Sunx. -

LF Ruffer Japanese Fund

LF Ruffer Japanese Fund Providing capital growth by investing in a portfolio of Japanese equities December 2020 Issue 124 Investment objective During the three month period from 1 October to 31 December the price of the fund’s O accumulation shares increased by 12.0% while the FTSE Japan Total Return Index on a sterling The investment objective of LF Ruffer Japanese Fund is to provide capital growth by investing in a adjusted basis and in yen went up by 8.8% and 12.3% respectively. The top contributors to portfolio of predominantly Japanese equities, though Japanese fixed income securities and fixed performance over the quarter were M3, Sony, ORIX, Murata Manufacturing and Sumco. The largest income securities and equities from other geographical areas may be utilised if the Investment negative contributors were NEC, Rakuten, JCR Pharmaceutical, Santen Pharmaceutical and the JPY/ Manager believes they will assist in meeting the overall objective of the sub fund. The fund may also GBP forex forward contract. invest in collective investment schemes, cash, money market instruments, other transferable securities For the calendar year 2020, the fund’s O accumulation shares generated a return of 31.5% while and derivatives and forward transactions and other investments to the extent that each is permitted by the FTSE Japan Total Return returned 11.5% in sterling and 8.9% in yen. Regarding attribution for the the regulations. There will be no particular emphasis on any industrial or economic sector. calendar year 2020, M3, Daiichi Sankyo, Lifenet Insurance, Fujitsu and Keyence were the biggest Performance since launch on 14 May 2009 positive contributors while ORIX, Tokio Marine, Mandom, East Japan Railway and Recruit provided the largest negative contributions. -

General Catalog

AutoID General Catalog BARCODE READERS 2D CODE READERS AUTO ID DATA CONTROLLERS Evolving systems that have overwhelming performance and reliability. Read! Visualize! A new algorithm, created from years of The reading status can be checked at a experience, provides the best-in-class glance! These products support stable reading capabilities. operation by visualizing the reading margin. 2 SR-750 EtherNet/IP+PoE Stable reading for SR-750 Series difficult-to-read 1D and P.6 2D codes Camera type SR-D100 DPM Model 2D High Performance SR-D100 Series Reader P.8 SR-600 Ultra Compact Powerful compact SR-600 Series system P.12 Connect! Fixed-type readers BL-1300 Digital, Laser Type High speed and BL-1300 Series high resolution P.14 1D compact code reader Laser/CCD BL-700 Long-range, Laser Type Ultra long range and BL-700 Series outstanding angle P.16 capabilities BL-180 Ultra Compact, CCD Type Ultra-compact size, BL-180 Series half the size of a business card Fixed-type readers P.17 Auto ID Data Controller Verifies and evaluates DV-90 DV-90 Series data and converts data to P.20 I/O signals RS-485 Master Unit N-410 Supports Multi-Drop N-410 Series and Multi-Head Mode TCP/IP P.21 Communication RS-232C Selectable to match Power Supply/ Peripheral equipment Dedicated Power Supply/ the specifications of Communication Units Communication with a variety of the device being P.22 connected to controllers, such as PLCs and laser HR-100 HR-100 markers, is possible! This makes it possible 2D Code Model Wide target area and to construct systems to match their HR-100 Series high-speed response environments. -

Keyence Products Catalogue

NEW PRODUCTS LINE-UP CATALOGUE LINE-UP TOTAL SENSING SOLUTIONTOTAL MICROSCOPE VISION SYSTEM MEASUREMENT SAFETY LIGHT CURTAIN LASER SENSOR FIBRE OPTIC WHY IS KEYENCE UNIQUE? Corporate Information Global Headquarters: Osaka, Japan Founded: May 1974 Capital: $364,728,000 USD 2011 Global Sales: $2,373,023,000 USD Worldwide Employees: 3,420 Dollar amounts are translated from Japanese yen, for convenience only, at ¥84 = US$1, the approximate exchange rate on March 20, 2012. An Exceptional Company KEYENCE has been named one of Business Week’s “1000 Best Valued Companies” and consistently ranked ahead of companies such as Sony and Honda Motors in Japan’s Nikkei, Tokyo Stock Exchange, Newspaper’s ranking of the “Top Ten Excellent Companies in Japan.” KEYENCE Global Headquarters, Osaka, Japan Exceptional Performance and results Newsweek Electronics Nikkei Newspaper Industry Ranking KEYENCE consistently ranks in the “top ten” in the Nikkei newspaper’s annual ranking of “excellent companies” in Japan. 1 IBM 2 HP ❙ Maintains its ranking in top 30 (for 20 years) 3 CANON INC. ❙ Ranked 1st twice (1995,1996) 4 Panasonic ❙ Ranked in the top 10 from 2005 to 2008 5 Apple INC. 6 ABB 7 DELL Recent Top 10 8 Schneider Electric 1 Nintendo 9 Emerson Electric 2 FANUC LTD. 10 Sony 3 Astellas Pharma Inc. … 16 Xerox 4 Takeda Pharmaceutical … 5 KEYENCE 26 Seagate 6 ROHM CO.,LTD. … 7 CANON INC. 39 KEYENCE 8 Trend Micro Inc. … 42 Rockwell Automation 9 TOYOTA Motor Corp 10 NTT DOCOMO,INC. … 2 DEDICATED TO ADDING VALUE FOR OUR CUSTOMERS Direct Sales KEYENCE employs DIRECT Sales Engineers for product support and on-site consultation. -

3-Axis LASER MARKER

3-Axis LASER MARKER GENERAL CATALOG Who We Are KEYENCE has steadily grown since 1974 to become an innovative leader in the development and manufacturing of automation equipment worldwide. Our products consist of automation sensors, measuring instruments, vision systems, laser markers, and digital microscopes. Our innovative products not only meet current needs but also future customer requirements in many manufacturing and research industries. We strive to anticipate the market’s future needs to provide tomorrow’s solution today. At KEYENCE, we are not content to only have the best products on the market, we also strive to provide our customers with the most knowledgeable and trained sales professionals in the industry. We are dedicated to supporting our customers and working with them to achieve their goals. KEYENCE, a blue chip company, has been named one of Business Week’s “1000 Best Valued Companies”. We are also in the top 50 of Newsweek’s electronic industry ranking and are consistently ranked in Japan’s Nikkei Newspaper’s yearly list of the “Top Ten Excellent Companies in Japan”. Today, KEYENCE serves over 100,000 customers in some 70 countries around the world, where its name stands for innovation and excellence. Direct Approach KEYENCE employs a large number of sales engineers throughout the world enabling invaluable direct on-site support. With this direct approach, we are able to meet the customer’s needs at every level of their business, from the design and research stage to the production line and beyond. These highly trained sales engineers are problem solvers who can provide real solutions to our customers’ applications with existing products or potential new solutions. -

Calvert VP EAFE International Index Portfolio 1St Quarter Holdings

Calvert VP EAFE International Index Portfolio March 31, 2020 Schedule of Investments (Unaudited) Common Stocks — 98.5% Security Shares Value Australia (continued) Security Shares Value Australia — 5.8% Ramsay Health Care, Ltd. 1,442 $ 50,704 REA Group, Ltd. 537 25,155 AGL Energy, Ltd. 6,090 $ 63,734 Rio Tinto, Ltd. 3,172 163,420 Alumina, Ltd.(1) 14,501 12,996 Santos Ltd., 13,517 27,761 AMP,Ltd.(1)(2) 22,416 18,306 Scentre Group 45,895 43,959 APA Group(1) 11,361 72,094 Seek, Ltd.(1) 3,323 30,366 Aristocrat Leisure, Ltd. 4,773 61,847 Sonic Healthcare, Ltd. 4,020 60,420 ASX, Ltd. 1,623 76,185 South32, Ltd. 48,353 53,377 Aurizon Holdings, Ltd. 16,477 42,701 Stockland 19,317 29,704 AusNet Services(1) 27,031 28,383 Suncorp Group, Ltd.(1) 11,330 62,918 Australia & New Zealand Banking Group, Ltd. 24,210 253,900 Sydney Airport 8,748 30,225 Bendigo & Adelaide Bank, Ltd. 4,706 18,080 Tabcorp Holdings, Ltd.(1) 15,814 24,474 BGP Holdings PLC(2)(3) 77,172 — Telstra Corp., Ltd. 37,215 69,858 BHP Group, Ltd. 26,250 476,209 TPG Telecom, Ltd.(1) 3,460 14,735 BlueScope Steel, Ltd. 4,388 22,973 Transurban Group(1) 24,274 180,808 Boral, Ltd. 10,917 13,712 Treasury Wine Estates, Ltd. 6,449 40,039 Brambles, Ltd. 14,024 90,648 Vicinity Centres 25,959 16,238 Caltex Australia, Ltd. 1,867 25,210 Washington H. -

Changes to the Nikkei Stock Average

PRESS RELEASE a sample translation original release in Japanese September 6, 2021 Nikkei Inc. Changes to the Nikkei Stock Average Nikkei Inc. will make the following changes to the Nikkei Stock Average (Nikkei 225) constituents as a result of the annual review. This release also includes the changes to the presumed par value in response to the stock split and the stock consolidation (reverse split) of the constituents. Please note that “Change from Presumed Par Value to Price Adjustment Factor” and “Maximum number of constituents reshuffle” in the “Changes to the Index Guidebook and the Constituents Selection Rules of the Nikkei Stock Average” announced dated July 5 become effective from this year’s annual reshuffle. 1. Constituents change because of the annual review Date Code Addition* Code Deletion KEYENCE CORPORATION 6861 3105 Nisshinbo Holdings Inc. (0.1) Murata Manufacturing Co., Oct. 1 6981 5901 Toyo Seikan Group Holdings, Ltd. Ltd. (0.8) 7974 Nintendo Co., Ltd. (0.1) 9412 SKY Perfect JSAT Holdings Inc. * Number in the parenthesis is Price Adjustment Factor. < Note > In accordance with the Constituents Selection Rules, KEYENCE (Technology sector), Murata Manufacturing (Technology sector), and Nintendo (Consumer goods/services sector) will be added because of high liquidity. Nisshinbo (Technology sector), Toyo Seikan Group (Materials sector), SKY Perfect JSAT (Technology sector) will be deleted as a result of the adjustment of the number of constituents among sectors (deleted from the over-weighted sector). These changes will be made before the opening of the market on October 1. * “Sectors” are industrial sectors defined by aggregating Nikkei 36 industry classification system into 6 broad categories. -

PDF Download

TOKYO ELECTRON ANNUAL REPORT 2020 For the Year Ended March 31, 2020 PR58-126 TOKYO ELECTRON ANNUAL REPORT 2020 PAGE 1 Business Overview Review of Operations Financial Section To Our Stakeholders Interview with the CEO Corporate Governance and Financial Highlights and Business Outlook Investor Information Contents Guide to Buttons Move Back to Previous Page Contents Move Forward to Next Page Corporate Philosophy Return to Last Page Opened 2 To Our Stakeholders We strive to contribute to the develop- Go to Contents Page ment of a dream-inspiring society 3 Business Overview and Financial Highlights through our leading-edge technologies 4 Interview with the CEO Search PDF Content and reliable service and support. 7 Review of Operations and Business Outlook Print 8 Message from the Chairman of the Board Zoom Vision 9 Corporate Governance 12 Directors, Audit & Supervisory Board Members and A truly global company generating Executive Officers high added value and profits 13 Financial Section in the semiconductor and 29 Consolidated Subsidiaries flat panel display industries through innovative technologies and 29 Investor Information groundbreaking proactive solutions that integrate diverse technologies. The Corporate Philosophy defines the pur- pose of Tokyo Electron’s existence and its mission in society. It represents Tokyo Disclaimer Electron’s basic way of thinking and forms Matters discussed in this annual report, including forecasts of future business performance of Tokyo Electron, management strategies, beliefs and other statements are based on Tokyo Electron’s assumptions in light of information that is currently the foundation for its corporate activities. available. These forward-looking statements involve known or unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors that could The Vision describes Tokyo Electron’s cause actual results to differ materially from those referred to in the forward-looking statements. -

High-Performance Vision System Powerful, Flexible, Versatile

NEW Customizable Vision System XG-X Series High-Performance Vision System Powerful, Flexible, Versatile XG-X Series 21 Megapixel Cameras One System To Solve All Image Processing Needs A versatile vision system that offers a variety of different camera types and image capturing functions to solve a wide range of application needs. One platform that provides a powerful solution to the problems faced by customers now and flexible enough to address future needs. Multi-Spectrum Image Capture 2 LumiTrax™ In-Line 3D Inspection Line Scan Cameras Vision-Guided Robots 3 The World’s Highest-Performing, Multi-Core Processors Make It Possible to Combine Multiple Cameras and Lighting Becoming the leader in application solving requires powerful hardware. Optimizing the 14 cores enables stable, high-speed solutions, even for the most complicated inspections. 4 Stable, high-speed performance is made possible with parallel processing by 14* cores, the largest offering in the industry. DSP + CPU Abundant processing power is available to handle multiple camera connections including up to 21 megapixel color/monochrome cameras, up to 7 cores for 8K line scan cameras, and 3D profilers/cameras. arithmetic Large built-in image memory on the controller operation allows online storage over 28K images (VGA color) for easy trouble-shooting and 2 cores for 3 cores for display control maintenance of the system. 21 megapixel color camera defect inspection processing speed XG-8702 70.3 ms CPU Approx. 1/3 XG-X2902 2 cores for 21.9 ms the processing time display and control * XG-X2702/X2802/X2902 has 14 cores. XG-X2002/X2202/X2502 has 8 cores. -

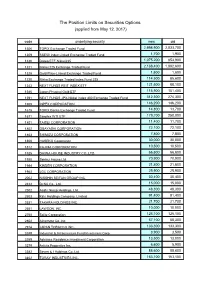

The Position Limits on Securities Options (Applied from May 12, 2017) Code Underlying Security New Old

The Position Limits on Securities Options (applied from May 12, 2017) code underlying security new old 1306 TOPIX Exchange Traded Fund 2,998,900 2,033,700 1309 SSE50 Index Linked Exchange Traded Fund 1,700 1,900 1320 Daiwa ETF-Nikkei225 1,075,200 853,900 1321 Nikkei 225 Exchange Traded Fund 2,168,400 1,882,600 1328 Gold-Price-Linked Exchange Traded Fund 1,600 1,600 1330 Nikko Exchange Traded Index Fund 225 114,500 85,600 1343 NEXT FUNDS REIT INDEX ETF 121,600 88,100 1540 Japan Physical Gold ETF 116,900 101,400 1591 NEXT FUNDS JPX-Nikkei Index 400 Exchange Traded Fund 312,300 274,300 1605 INPEX CORPORATION 146,200 146,200 1615 TOPIX Banks Exchange Traded Fund 14,800 13,700 1671 Simplex WTI ETF 179,700 250,000 1801 TAISEI CORPORATION 11,400 11,700 1802 OBAYASHI CORPORATION 72,100 72,100 1803 SHIMIZU CORPORATION 7,800 7,800 1808 HASEKO Corporation 30,000 30,000 1812 KAJIMA CORPORATION 10,500 10,500 1925 DAIWA HOUSE INDUSTRY CO.,LTD. 66,600 66,600 1928 Sekisui House,Ltd. 70,900 70,900 1944 KINDEN CORPORATION 21,800 21,800 1963 JGC CORPORATION 25,900 25,900 2002 NISSHIN SEIFUN GROUP INC. 30,400 30,400 2432 DeNA Co., Ltd. 15,000 15,000 2502 Asahi Group Holdings, Ltd. 48,300 48,300 2503 Kirin Holdings Company, Limited 91,400 91,400 2531 TAKARA HOLDINGS INC. 21,700 21,700 2651 LAWSON, INC. 10,000 10,000 2768 Sojitz Corporation 125,100 125,100 2802 Ajinomoto Co.,Inc.