Claire Messud Discusses "The Burning Girl"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ONLINE HARASSMENT of JOURNALISTS Attack of the Trolls

ONLINE HARASSMENT OF JOURNALISTS Attack of the trolls 1 SOMMAIREI Introduction 3 1. Online harassment, a disinformation strategy 5 Mexico: “troll gangs” seize control of the news 5 In India, Narendra Modi’s “yoddhas” attack journalists online 6 Targeting investigative reporters and women 7 Censorship, self-censorship, disconnecting and exile 10 2. Hate amplified by the Internet’s virality 13 Censorship bots like “synchronized censorship” 13 Troll behaviour facilitated by filter bubbles 14 3. Harassment in full force 19 Crowd psychology 3.0: “Anyone can be a troll” 19 Companies behind the attacks 20 Terrorist groups conducting online harassment 20 The World Press Freedom Index’s best-ranked countries hit by online harassment 20 Journalists: victims of social network polarization 21 4. Troll armies: threats and propaganda 22 Russia: troll factory web brigades 22 China: “little pink thumbs,” the new Red Guards 24 Turkey: “AK trolls” continue the purge online 25 Algeria: online mercenaries dominate popular Facebook pages 26 Iran: the Islamic Republic’s virtual militias 27 Egypt: “Sisified” media attack online journalists 28 Vietnam: 10,000 “cyber-inspectors” to hunt down dissidents 28 Thailand: jobs for students as government “cyber scouts” 29 Sub-Saharan Africa: persecution moves online 29 5. RSF’s 25 recommendations 30 Tutorial 33 Glossary 35 NINTRODUCTIONN In a new report entitled “Online harassment of journalists: the trolls attack,” Reporters Without Borders (RSF) sheds light on the latest danger for journalists – threats and insults on social networks that are designed to intimidate them into silence. The sources of these threats and insults may be ordinary “trolls” (individuals or communities of individuals hiding behind their screens) or armies of online mercenaries. -

China's Cyber-Influence Operations

Maj Gen PK Mallick, VSM (Retd) | 1 © Vivekananda International Foundation Published in 2021 by Vivekananda International Foundation 3, San Martin Marg | Chanakyapuri | New Delhi - 110021 Tel: 011-24121764 | Fax: 011-66173415 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.vifindia.org ISBN: 978-81-952151-7-1 Follow us on Twitter | @vifindia Facebook | /vifindia Disclaimer: The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct Cover Image Source : https://www.recordedfuture.com All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. One of the foremost experts on Cyber, SIGINT and Electronic Warfare. Maj Gen PK Mallick, VSM (Retd) is a graduate of Defence Services Staff College and M Tech from IIT, Kharagpur. He has wide experience in command, staff and instructional appointments in Indian Army. He has also been a Senior Directing Staff (SDS) at National Defence College, New Delhi. Presently, he is a Consultant with the Vivekananda International Foundation, New Delhi. China’s Cyber-Influence Operations “Wherever the readers are, wherever the viewers are, that is where propaganda reports must extend their tentacles”,— Xi Jinping, February 2016 Introduction The digital era has transformed the way we communicate. Using social media like Facebook and Instagram, and social applications such as WhatsApp and Telegram, one can be in contact with friends and family, share pictures, videos, messages, posts and share our experiences. -

LITTLE PINK HOUSE a True Story of Defiance and Courage

LITTLE PINK HOUSE A True Story of Defiance and Courage Jeff Benedict & Scott Bullock Center of the American Experiment is a nonpartisan, tax-exempt, public policy and educational institution that brings conservative and free market ideas to bear on the hardest problems facing Minnesota and the nation. MARCH 2010 LITTLE PINK HOUSE A True Story of Defiance and Courage JEFF BENEDICT & SCOTT BULLOCK Jointly Sponsored by The Federalist Society – Minnesota Lawyers Chapter Institute for Justice – Minnesota Chapter Center of the American Experiment Introduction More often than not, those studies were filled with the same modern planning-speak about the Before there were Tea Parties, there was Kelo. importance of “redevelopment and revitalization” Susette Kelo’s name turned into a movement. in a “public transport centric manner” to create a Her loss of her property was the final straw for “gateway community” with “upscale amenities” and Americans in 2005. When they heard about the “large anchors” designed under “smart growth tools” Kelo decision, homeowners and small businesses to ensure “sustainability” and conducted under the across this country refused to accept the idea that auspices of a “public-private partnership.” a well-connected developer could turn city hall into a real estate broker and force a hardworking, Well, Susette Kelo personified the opposition to honest, middle-aged nurse to leave her home all of that gobbledygook and Americans knew that for the economic benefits accruing to a large those words just meant two things for them: that pharmaceutical company and the political benefits corporate welfare now extended to land grabs, and accruing to a soon-to-be jailed governor. -

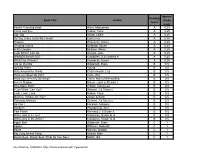

Book Title Author Reading Level Approx. Grade Level

Approx. Reading Book Title Author Grade Level Level Anno's Counting Book Anno, Mitsumasa A 0.25 Count and See Hoban, Tana A 0.25 Dig, Dig Wood, Leslie A 0.25 Do You Want To Be My Friend? Carle, Eric A 0.25 Flowers Hoenecke, Karen A 0.25 Growing Colors McMillan, Bruce A 0.25 In My Garden McLean, Moria A 0.25 Look What I Can Do Aruego, Jose A 0.25 What Do Insects Do? Canizares, S.& Chanko,P A 0.25 What Has Wheels? Hoenecke, Karen A 0.25 Cat on the Mat Wildsmith, Brain B 0.5 Getting There Young B 0.5 Hats Around the World Charlesworth, Liza B 0.5 Have you Seen My Cat? Carle, Eric B 0.5 Have you seen my Duckling? Tafuri, Nancy/Greenwillow B 0.5 Here's Skipper Salem, Llynn & Stewart,J B 0.5 How Many Fish? Cohen, Caron Lee B 0.5 I Can Write, Can You? Stewart, J & Salem,L B 0.5 Look, Look, Look Hoban, Tana B 0.5 Mommy, Where are You? Ziefert & Boon B 0.5 Runaway Monkey Stewart, J & Salem,L B 0.5 So Can I Facklam, Margery B 0.5 Sunburn Prokopchak, Ann B 0.5 Two Points Kennedy,J. & Eaton,A B 0.5 Who Lives in a Tree? Canizares, Susan et al B 0.5 Who Lives in the Arctic? Canizares, Susan et al B 0.5 Apple Bird Wildsmith, Brain C 1 Apples Williams, Deborah C 1 Bears Kalman, Bobbie C 1 Big Long Animal Song Artwell, Mike C 1 Brown Bear, Brown Bear What Do You See? Martin, Bill C 1 Found online, 7/20/2012, http://home.comcast.net/~ngiansante/ Approx. -

Chinese Nationalism, Cyber-Populism, and Cross-Strait Relations

Chinese Nationalism, cyber-populism, and cross-strait relations Ye Weili; Michael Toomey Wenzhou-Kean University THIS IS A PRELIMINARY, INCOMPLETE FIRST DRAFT PREPARED FOR THE 2017 ISA INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE IN HONG KONG: DO NOT CITE OR CIRCULATE WITHOUT THE AUTHOR’S PERMISSION Abstract: In November 2015, a Taiwanese singer named Chou Tzuyu appeared on a Korean TV show as a member of the pop group ‘Twice’. During the show, she claimed that she was from Taiwan (without mentioning China), and waved the Republic of China flag. Chou was subsequently the recipient of vociferous condemnation from Chinese ‘netizens’, and eventually was compelled to make a public apology for her actions. This apology became the center of an Internet-based dispute between the netizens of mainland China and Taiwan, conducted mainly on the Facebook page of then Taiwanese Presidential candidate, Tsai Yingwen. Subsequently, the tone of this dispute had significant effects on the 2016 Taiwanese general election, with a decisive number of Taiwanese voters switching their support to Tsai. “Cyber-populism”, and the online activities of nationalistic Chinese netizens, are not just limited to the Chou Tzuyu incident. Indeed, Chinese netizens have been vocal in the wake of other international incidents, such as the United Nations Convention ruling on the so-called “Nine-Dash Line” dispute. However, the Chou Tzuyu case was particularly notable for its clearly counterproductive outcome: an argument over the use of Taiwanese symbols of nationalist identity, driven by the identities and objectives of Chinese nationalists, contributed to the electoral success of a pro-Taiwanese independence political party. With this in mind, this paper examines the relationship between Chinese nationalism and cyber-populism, and discusses the effects of this phenomenon on the achievement of China’s stated foreign policy goals. -

Laugh Your Way to Victory

CHAPTER V Laugh Your Way to Victory want you to take a moment and play one of my favorite I games. It’s called “Pretend Police.” It’s fun. Here goes. Pretend you’re the police in Ankara, Turkey. A few days ago, security guards in one of the busiest subway stations in town spotted a couple making out on the platform. Strict Muslims, the guards were bugged by such immodest behavior in public, so they did the only thing they could really do, 98 Blueprint for Revolution which was get on the subway’s PA system and ask all passen- gers to behave themselves and stop kissing each other. Be- cause everyone in Ankara has smartphones, this little incident was leaked to the press within minutes; by the afternoon, politicians opposed to the ruling Islamist-based party realized that they had gold on their hands and started encouraging their supporters to stage huge demonstrations to protest this silly anti- smooching bias. This is where you come in. On Sat- urday, the day of the demonstration, you show up in uni- form, baton at hand, ready to keep the peace. Walking into the subway station, you see more than a hundred young men and women chanting anti-government slogans and provoking your colleagues. Someone shoves someone. Someone loses their cool. Soon it’s a full- blown riot. If you’re seriously playing along, it’s probably not hard to figure out what to do. You’re a police officer, and you’ve probably spent a whole week at the academy training for situ- ations just like this. -

Little Pink Flower with a Darker Story to Tell: the Role of Emojis in Online Human Trafficking Andotential P FOSTA-SESTA Liability

University of Miami Race & Social Justice Law Review Volume 11 Issue 1 Article 5 November 2020 Little Pink Flower with a Darker Story to Tell: The Role of Emojis in Online Human Trafficking andotential P FOSTA-SESTA Liability Olivia Parise Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umrsjlr Part of the Law and Race Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Olivia Parise, Little Pink Flower with a Darker Story to Tell: The Role of Emojis in Online Human Trafficking and Potential FOSTA-SESTA Liability, 11 U. Miami Race & Soc. Just. L. Rev. 52 (2020) Available at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umrsjlr/vol11/iss1/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Race & Social Justice Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Little Pink Flower with a Darker Story to Tell: The Role of Emojis in Online Human Trafficking and Potential FOSTA-SESTA Liability Olivia Parise* There seems to be an emoji for every expression, thought, and feeling – even for human traffickers. Emojis have evolved into a primary lexicon for online human trafficking. This coded language has allowed online human traffickers to evade detection and prosecution. Courts and law enforcement are confused by the seemingly innocent use of emojis in advertisements and conversations that have serious human trafficking implications. Now, the code is cracked. -

Volume 22 • 2021 Volume

Volume 22 • 2021 The breeze barely dares to breathe, The October sun was deceiving, yet the blossom tree shifts in a shining so bright in the cold. gentle sway. Kaleidoscopic sunbursts However, the salve of intoxication of magenta, chartreuse, and faded protected me from the bite of the blue bridge the small gulf between autumn breeze. lashed lids as your eyes squint in the Jacob William Linke brightness, dragging the corners of “Fall Break” your mouth upward. Volume 22 Volume Cecelia Bialas “Seasonal Effective” Watching the flowers dance to the rhythm of the singing, swaying grass. Teresa Burt In the summer heat, the trees are “My Soul” adorned with vibrant dark green 2021 leaves at high noon, which changes to a lighter yellow-green as the Just then, turning that first corner at sun starts to dip down behind the end of the mile from the church, I the horizon. Children play in the saw it. I saw my first glimpse of hope. background in the yard of a small Fluttering from every ditch were small cute house on the other side of orange Monarchs, thousands of them the street. Their laughter carries rising out of the tall golden grass-like throughout the world around them. graceful little angels. Kaita Baird Jennifer Wood “Hidden Gem” “Gabby Sleeps” A magazine of creative expression by students, faculty, and staff at Southeast Community College Beatrice/Lincoln/Milford, NE Falls City/Hebron/Nebraska City/Plattsmouth/Wahoo/York, NE Volume 22 2021 “If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.” Toni Morrison Illuminations Volume 22 Editor: Tammy Jolene Zimmer Graphic Designer: Nathan Comstock Editorial Team: Cheney Luttich, Michaela Hartman, Heather Ann Sticka, Teresa Burt, Logan Metzler, Ashley Hoover, Trina Uwineza, Marge Itzen, and Stewart Haszard. -

Curriculum Vitae

University of Missouri Missouri School of Journalism Assistant Professor of Strategic August 2017 - present Communication Department of Communication, College of Arts & Sciences Courtesy Faculty January 2018 - present School of Health Professions, Master of Public Health Affiliate Faculty April 2020 – present Missouri School of Journalism University of Kansas 178 Gannett Hall William Allen White School of Columbia, MO 65211 Journalism and Mass Communications (573)-884-0170 Lecturer May 2017 – August 2017 [email protected] Teaching Assistant/Instructor August 2013 – May 2017 of Record Faculty Website PEER-REVIEWED JOURNAL ARTICLES Luisi, M. (2020). From bad to worse: The representation Ph.D., Journalism of the HPV vaccine Facebook. Vaccine. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.05.016. and Mass Luisi, M. (2020). Kansan parent/guardian perceptions of Communication HPV and the HPV vaccine and the role of social University of Kansas | 2017 media. Kansas Journal of Medicine, 13(1), 9-18. ”M.A., Luisi, M., Jones, R., & Luisi, T. (2020). Randall Pearson: Communication Studies Framing Black identity, masculinity, adoption and mental health in television. Howard Journal of University of South Dakota Communications, 31(1), 71-85. doi: | 2013 10.1080/10646175.2019.1608481 B.A., Communication Luisi, M., Rodgers, S., & Schultz, J. (2019). Experientially Studies learning how to communicate science effectively: A University of Maryland | case study. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 56(8), 1135-1152. doi: 2010 10.1002/tea.21554 Certificate: African- American Studies Minor: Spanish Language & Cultures 1 MONIQUE LUISI | CURRICULUM VITAE Luisi, M., Barker, J., & Geana, M. (2018). American Ebola Story: Frames in U.S. national newspapers. Atlantic Journal of Communication, 26(5), 267-277. -

The Covid-19 Pandemic and the Estrangement of US-China Relations

The Covid-19 Pandemic and the Estrangement of US-China Relations Dali L. Yang This article assesses US-China relations during the Covid-19 pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, the US-China trade war created an atmosphere of bitterness and mistrust in bilateral relations and also prompted the Chinese leadership to seek to enhance its “discourse power” through “wolf warrior” diplomacy. This atmosphere hampered US-China communi- cation and cooperation during the initial phase of the pan- demic. The unleashing of “wolf warrior” diplomacy as the pandemic spread round the world, especially in the United States, has exacerbated US-China relations and served to ac- celerate the transition of US policy toward China from con- structive engagement to strategic competition. Keywords: COVID-19, wolf warrior diplomacy, US-China trade war, US-China relations, pandemic psychology. PANDEMICS SUCH AS COVID-19 NOT ONLY CAUSE SICKNESS AND DEATH BUT also induce mega socioeconomic and psychological shocks. As the American Psychological Association states, the Covid-19 “coronavirus pandemic is an epidemiological and psychological crisis. The enormity of living in isolation, changes in our daily lives, job loss, financial hard- ship and grief over the death of loved ones has the potential to affect the mental health and well-being of many” (American Psychological Asso- ciation 2020). The pandemic has contributed to stress, anxiety, and even panic in individuals, conflict and abuse in some families, and intergroup tensions through avoidance, blame, stigmatization, and conflict over re- sources (Dubey et al. 2020). In examining the relationship between pandemics and public policy, of which foreign policy is a key dimension, much of the attention is on the harm to and protection of individuals, families, and social groups. -

The Chautauqua Journal, Complete Volume 2: Living with Others

Volume 2 Living With Others / Crossroads Article 3 2018 The hC autauqua Journal, Complete Volume 2: Living with Others / Crossroads Follow this and additional works at: https://encompass.eku.edu/tcj Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, Education Commons, Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation (2018) "The hC autauqua Journal, Complete Volume 2: Living with Others / Crossroads," The Chautauqua Journal: Vol. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://encompass.eku.edu/tcj/vol2/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in The hC autauqua Journal by an authorized editor of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. et al.: TCJ Volume 2: Living with Others / Crossroads ERIK LIDDELL INTRODUCTION This second volume of The Chautauqua Journal combines submissions related to the 2011-12 series on “Living with Others” and the 2012-13 series on “Crossroads,” with the inclusion also of an extra piece by Lee Dugatkin arising from the 2017-18 “Transformations” series that describes the background to the famous Russian domesticated fox experiment and that serves as a sort of companion piece to Mark Rowlands’ reflections on the philosopher and the wolf. Unlike the first volume of the journal, which was divided into sections focusing on philosophical and cultural investigations, artistic expressions and scientific interventions, in the interdisciplinary and comparative spirit of the lecture series from which the journal takes inspiration, this second volume encourages the reader to explore the contributions without the apparatus of section headers, through juxtaposition and through sequential or associative browsing. -

China's Expanding Global Media Dominance and the Chinese Diaspora

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive DSpace Repository Theses and Dissertations 1. Thesis and Dissertation Collection, all items 2019-12 THE MANCHURIAN QUESTION: CHINA’S EXPANDING GLOBAL MEDIA DOMINANCE AND THE CHINESE DIASPORA Padua, Justin V.; Liu, Austin Y. Monterey, CA; Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/64041 Downloaded from NPS Archive: Calhoun NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS THE MANCHURIAN QUESTION: CHINA’S EXPANDING GLOBAL MEDIA DOMINANCE AND THE CHINESE DIASPORA by Justin V. Padua and Austin Y. Liu December 2019 Thesis Advisor: Timothy C. Warren Second Reader: Christopher P. Twomey Approved for public release. Distribution is unlimited. THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Form Approved OMB REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington, DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED (Leave blank) December 2019 Master’s thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS THE MANCHURIAN QUESTION: CHINA’S EXPANDING GLOBAL MEDIA DOMINANCE AND THE CHINESE DIASPORA 6. AUTHOR(S) Justin V. Padua and Austin Y.