Anton Coppola: Maestro …By All Means! Published on Iitaly.Org (

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'opera Famiglia PR .Qxp Layout 1

November 10, 2020 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: James Cassidy (859) 431-6216 [email protected] L’Opera Famiglia (Two couples, great arias) 7:30 p.m. November 21, 2020 St. Peter in Chains Cathedral Basilica 8th and Plum Cincinnati, OH The Kentucky Symphony Orchestra continues its 29th season of in-person performances and live streaming with an evening of operatic and sacred arias. The KSO, over the last 20 seasons, has offered audiences complete concert operas — Tosca, Otello, La Boheme, Rigoletto, Samson & Delilah and Turandot. These productions featured a number of internationally recognized singers, many with local ties (CCM and the Cincinnati Opera). Four of these artists return as two couples for L’Opera Famiglia on November 21 at the Cathedral Basilica of St. Peter in Chains. Mezzo soprano Stacey Rishoi appeared in a KSO “Sopranos” evening and as Delilah (Samson & Delilah). Her husband Gustav Andreassen (bass) sang the role of Sparafucille (Rigoletto). Stacey and Gus when not on the road reside Bellevue, KY. Stuart Neill KSO at St. Peter in Chains Cathedral Feb. 23, 2020 (tenor) and Sandra Lopez (soprano) met as Rodolfo and Mimi in the KSO’s 2007 production of La Boheme. They were married a couple years later and live in Miami. “As with any team sport or artistic collaboration, cast chemistry is vital for success. We were fortunate for the stars to align to find these wonderful performers available this week,” commented KSO music director, James Cassidy. Those who don’t think that opera is their cup of tea, might be surprised to find many of the selections on the program very familiar to a universal audience (see below). -

Msm String Chamber Orchestra

Tuesday, April 20, 2021 | 12:15 PM Livestreamed from Neidorff-Karpati Hall MSM STRING CHAMBER ORCHESTRA George Manahan (BM ’73, MM ’76), Conductor PROGRAM ADOLPHOUS HAILSTORK Church Street Serenade (BM ’63, MM ’65, HonDMA ’19) (b. 1941) EDVARD GRIEG Holberg Suite, Op. 40 (1843–1907) Praeludium (Allegro vivace) Sarabande (Andante) Gavotte (Allegretto) Air (Andante religioso) Rigaudon (Allegro con brio) HEITOR VILLA-LOBOS Bachianas Brasileiras No. 1 (1887–1959) MSM STRING CHAMBER ORCHESTRA VIOLIN 1 VIOLA Tom Readett BASS YouJin Choi Ramon Carrero Mystic, Connecticut Dante Ascarrunz Seoul, South Korea Caracas, Venezuela Rei Otake Lafayette, Colorado Sophia Stoyanovich Sara Dudley Tokyo, Japan Jakob Messinetti Bainbridge Island, Washington New York, New York Sam Chung Lawrence, New York Young Ye Roh Seoul, South Korea Ridgewood, New Jersey CELLO Rachel Lin Noah Koh San Jose, California VIOLIN 2 Bayside, New York Nicco Mazziotto Da Huang Juedy Lee Melville, New York Beijing, China Seoul, South Korea Esther Kang Benjamin Hudak Seoul, Korea San Francisco, California ABOUT THE ARTISTS George Manahan, Conductor George Manahan is in his 11th season as Director of Orchestral Activities at Manhattan School of Music, as well as Music Director of the American Composers Orchestra and the Portland Opera. He served as Music Director of the New York City Opera for 14 seasons and was hailed for his leadership of the orchestra. He was also Music Director of the Richmond Symphony (VA) for 12 seasons. Recipient of Columbia University’s Ditson Conductor’s Award, Mr. Manahan was also honored by the American Society of Composers and Publishers (ASCAP) for his “career-long advocacy for American composers and the music of our time.” His Carnegie Hall performance of Samuel Barber’s Antony and Cleopatra was hailed by audiences and critics alike. -

July/August 2017

L 'U nione Ital iana July August 2017 edit ion vol ume 19, issue 4 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Spaghetti Dinner... 4 CRUSH Happy Hour... 16-18 th 1731 East 7 Avenue Member Appreciation Night... 5 Fom the LAX President... 20 Tampa, Florida 33605 Italian Club Shoot... 5 "I Remember Mama"... 21 (813) 248-3316 Maestro Coppola... 6-8 Mother's Day Tea.. 22-23 www.italian-club.org Krewe Of Italia... 10 Campo Italiano... 24-25 Club Office Hours Shared Vacations... 11 Per I Bambini... 26 Monday-Friday 9:00am-5:00pm The Good Cemetarian... 12-13 Women Of Excellence...27 Cemetery Hours Comedy Spectacular... 13 Milestones... 28 Open Daily 8:00am-3:00pm Memorial Mass... 14 Thank You Festa Sponsors... 30 (Located at 26th St. & 24th Ave) Notte del Gala By OGGI... 15 Festa Scholarship... 31 MISSION STATEMENT The mission of L?Unione Italiana is to preserve and honor the culture, traditions and heritage of the Italian Community and to maintain the historical facility as a functioning memorial to the working class immigrants. We will support this mission through the dues and JULY contributions provided by the July 3rd & 4th CLUB CLOSED (Holiday) members, their families, July 23rd Italian Club Spaghetti Dinner (see page 4) friends, and government. In return we will add value to the July 28th Member Appreciation Night @ CRUSH Happy Hour membership by providing social activities, fellowship, AUGUST Italian arts and culture; these August 25th Member Appreciation Night @ CRUSH Happy Hour activities will provide for growth and stability in the membership, creating a safe SEPTEMBER and comfortable environment September 4th CLUB CLOSED (Holiday) for both members and employees. -

HUNGER GAMES Malnutrition Affects 35% of Mankind Are You in Danger Too? 10

US ISSUE ISSUE 2 • MAY - AUG 2019 US $4.25 YOUR LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE FOR HEART HEALTH NOW PLAYING: HUNGER GAMES Malnutrition affects 35% of mankind are you in danger too? 10 20 28 34 55 Risk Factor Chronic An active life at the Our Chef Recommends: Nature´s Medicine Inflammation: Defense amazing age of 102 Spring to Life with a Cabinet: Cayenne Pepper System Gone Rogue Fresh Start Captain Ward Bob Switzer invented Richard A. Amiello Invention of the invented neon colored paint for marked life-saving cork lifejackets safety vests K-15 Kevlar Vest sternum support vest 1865 1930 1975 2008 For centuries man has been striving to increase security, reduce pain and improve the quality of life. With a passion for care and a drive Products for postoperative for excellence Posthorax has taken on the challenge, providing the cardiac patient care. clinically proven, award-winning Posthorax Sternum Support Vest for patients a er cardiac and thoracic surgery. www.posthorax.com Advertisement Captain Ward Bob Switzer invented Richard A. Amiello Invention of the invented neon colored paint for marked life-saving cork lifejackets safety vests K-15 Kevlar Vest sternum support vest 1865 1930 1975 2008 For centuries man has been striving to increase security, reduce pain and improve the quality of life. With a passion for care and a drive Products for postoperative for excellence Posthorax has taken on the challenge, providing the cardiac patient care. clinically proven, award-winning Posthorax Sternum Support Vest for patients a er cardiac and thoracic surgery. -

Two Dramatically Different Views of Dance from the Early Twentieth Century by Francine L

Inside: Raleigh on Film; Bethune on Theatre; Behrens on Music; Trevens on Dance; Cole on Patrick Heron, “Color Magician”; Seckel on the Cultural Scene; Rossi ‘Speaks out’ on Online Exhibitions; New Art Books; Short Fiction & Poetry; Extensive Calendar of Events…and more! Vol. 29 No. 2 September/October 2012 Two Dramatically Different Views of Dance from the Early Twentieth Century By FrAncinE L. TrEvEnS Freud claimed there are no productions. her style presents a older generations. coincidences. therefore, i guess i crisp, clear and concise history of the mr. Franko, who must attribute to kismet the fact that musical phenomena, which dramati- authored many books two widely divergent books about cally altered social dancing. and won the 2011 Out- dance during the early-to-mid twen- the photos in this book have the standing Scholarly tieth century landed on my desk at same spontaneous feel as the danc- research in dance the same time. ers themselves had back in the day. award from the con- First to arrive was Rock ’n’ Roll the music was such, as ms Sagolla gress on research in Dances of the 1950s, by lisa Jo points out, that young people could dance, is Professor Sagolla, part of the american dance not merely listen, even if in a the- of dance at the uni- Floor series from Greenwood. ater. they had to move to the beat. versity of california, Second was mark Franko’s titled they danced on their seats and in Santa cruz; director Martha Graham in Love and War the aisles. of the center for Vi- subtitle The Life in the Work from a good deal of space is given to sual and Performance Oxford university Press. -

Msm String Chamber Orchestra

Saturday, February 20, 2021 | 12:15 PM Livestreamed from Neidorff-Karpati Hall MSM STRING CHAMBER ORCHESTRA George Manahan (BM ’73, MM ’76), Conductor PROGRAM J. S. BACH Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 in G Major, BWV 1048 (1685–1750) Allegro Adagio Allegro CARLOS SIMON Elegy (b. 1986) Dedicated to Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, and Michael Brown OTTORINO RESPIGHI Ancient Airs and Dances, Suite No. 3 (1879–1936) MSM STRING CHAMBER ORCHESTRA VIOLIN 1 VIOLIN 2 VIOLA CELLO DOUBLE BASS Carlos Martinez Basil Alter Kunbo Xu Noah Koh Dante Ascarrunz Arroyo Clinton, South Carolina Changsha, Hunan, China Bayside, New York Lafayette, Colorado Cabra, Córdoba, Spain Francesca Abusamra Jack Rittendale Eliza Fath Jakob Messinetti Shiqi Luo Rochester Hills, Michigan St. Louis, Missouri Fairfield, Connecticut Lawrence, New York Shanghai, China Maria Paparoni Zoe Daphnee Messiah Ahmed Caracas, Venezuela Lavoie-Gagne Dallas, Texas San Diego, California Students in this performance are supported by the Joseph F. McCrindle Scholarship and the Hans & Klara Bauer Scholarship. We are grateful to the generous donors who made these scholarships possible. For information on establishing a named scholarship at Manhattan School of Music, please contact Susan Madden, Vice President for Advancement, at 917-493-4115 or [email protected]. ABOUT THE ARTISTS George Manahan, Conductor George Manahan is in his 11th season as Director of Orchestral Activities at Manhattan School of Music, as well as Music Director of the American Composers Orchestra and the Portland Opera. He served as Music Director of the New York City Opera for 14 seasons and was hailed for his leadership of the orchestra. He was also Music Director of the Richmond Symphony (VA) for 12 seasons. -

Manhattan School of Music OPERA THEATER DONA D

Manhattan School of Music OPERA THEATER DONA D. VAUGHN, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Manhattan School of Music wishes to express its gratitude to the Joseph F. McCrindle Foundation for its generous endowment gif to fund Opera Theater productions. Manhattan School of Music is privileged to be able to honor the legacy of Joseph F. McCrindle through its Opera Studies Program. MSM OPERA THEATER Dona D. Vaughn, Artistic Director EMMELINE An opera in two acts by Tobias Picker (BM ’76) Based on the novel by Judith Rossner Libretto by J. D. McClatchy George Manahan (BM ’73, MM ’76), Conductor Thaddeus Strassberger, Director Used by arrangement with European American Music Distributors Company, sole U.S. and Canadian agent for Schott Helicon Music Corporation, publisher and copyright owner. For this production of Emmeline some sections of the original text and music have been amended by the composer and director to reflect the contemporary setting. THURSDAY–SATURDAY, APRIL 25–27, 2019 | 7:30 PM SUNDAY, APRIL 28, 2019 | 2:30 PM NEIDORFF-KARPATI HALL A warm welcome to MSM Opera Theater’s spring mainstage production in Neidorf-Karpati Hall! It has been a wonderful year for MSM Opera Theater as we have joined in the celebration of Manhattan School of Music’s Centennial, programming works that celebrate our past productions, our distinguished alumni composers, and our current talented young artists. Our opera season began in November at The Riverside Church with two performances of Opera Scenes. The program included scenes from Marc Blitzstein’s The Harpies (premiered at MSM in 1953), Scott Eyerly’s The House of the Seven Gables (premiered at MSM in 2000), Richard Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos, and Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi, which was given its first performance at the Metropolitan Opera in 1918, the year of MSM’s founding. -

Msm String Chamber Orchestra

Tuesday, January 26, 2021 | 12:15 PM Livestreamed from Neidorff-Karpati Hall MSM STRING CHAMBER ORCHESTRA George Manahan (BM ’73, MM ’76), Conductor PROGRAM HENRY PURCELL Suite from Abdelazer, Z. 570 (1659–1695) 1. Overture 2. Rondeau 3. Air 4. Air 5. Minuet 6. Air 7. Jig 8. Hornpipe 9. Air HANNAH KENDALL Citygates (b. 1984) JOHN ADAMS Shaker Loops (b. 1947) Shaking and Trembling Hymning Slews Loops and Verses A Final Shaking MSM STRING CHAMBER ORCHESTRA VIOLIN 1 VIOLIN 2 VIOLA CELLO DOUBLE BASS Jennifer Ahn Nicholas Pappone Nicholas Borghoff Molly Aronson Dylan Holly Omaha, Nebraska Pasadena, California Ridgewood, New Jersey Amherst, Massachusetts Tucson, Arizona Selin Algoz Carolyn Carr Toby Winarto Anthony de Pena Kyle Colina Istanbul, Turkey Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Los Angeles, California Miami, Florida Charlotte, North Carolina Hattie Hyei-Ri Ahn Audrey Jellett Daejeon, South Korea Kerrville, Texas ABOUT THE ARTIST George Manahan, Conductor George Manahan is in his 11th season as Director of Orchestral Activities at Manhattan School of Music, as well as Music Director of the American Composers Orchestra and the Portland Opera. He served as Music Director of the New York City Opera for 14 seasons and was hailed for his leadership of the orchestra. He was also Music Director of the Richmond Symphony (VA) for 12 seasons. Recipient of Columbia University’s Ditson Conductor’s Award, Mr. Manahan was also honored by the American Society of Composers and Publishers (ASCAP) for his “career-long advocacy for American composers and the music of our time.” His Carnegie Hall performance of Samuel Barber’s Antony and Cleopatra was hailed by audiences and critics alike. -

James Meena Conductor

James Meena Conductor James Meena consistently earns critical acclaim for his artistic vision and dynamic presence on the podium in concert, opera and ballet. Mo. Meena serves as Artistic Director for Opera Carolina (Charlotte) and Artistic Director for Opera Grand Rapids. Recent engagements include acclaimed performances of Turandot in the Teatro Antiche Taormina and Teatro Greco Siracusa, Tosca at the Luglio Festivale Trapani in Sicilia, a double- bill of Rachmaninoff’s rarely-performed Aleko paired with Pagliacci as well as La fanciulla del West, both with New York City Opera; Le nozze di Figaro for Teatro Sociale Rovigo Italy, La Fanciulla del West for five prestigious Italian theaters: Teatro del Giglio, Lucca Italy, Teatro Verdi in Pisa, Teatro Alighieri di Ravenna, Teatro Pavarotti di Modena and Teatro Goldoni di Livorno, plus Rigoletto, The Magic Flute, Carmen and Yvgeny Onegin with Opera Carolina and Opera Grand Rapids, a Gala concert with Renee Fleming and the Toledo Symphony Orchestra; Porgy & Bess with Margaret Island Open-Air Theatre in Budapest for their Summer Festival, and La bohème with the prestigious Puccini Festival in Torre del Lago, La bohème with Opéra de Montréal, and Masterworks Concerts with Memphis Symphony Orchestra. Next season, Mo. Meena makes his debut with the Shanghai Opera. A guest conductor, Maestro Meena has lead performances in opera houses throughout North America, including Madama Butterfly,Pagliacci/Gianni Schicchi, Le nozze di Figaro,and La traviata for L’Opera de Montreal; Michigan Opera Theatre for Die Zauberflöte; Edmonton Opera for Falstaff,Otello,Macbethand Eugene Onegin;an exciting new co-production of Roméo et Juliettewith Virginia Opera and Toledo Opera;and Manitoba Opera, where he conducted the première of Transit of Venusby the Canadian team of composer Victor Davies and librettist Maureen Hunter, recorded for national broadcast on the CBC. -

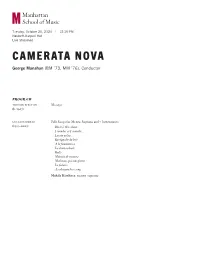

Camerata Nova

Tuesday, October 20, 2020 | 12:15 PM Neidorff-Karpati Hall Live Streamed CAMERATA NOVA George Manahan (BM ’73, MM ’76), Conductor PROGRAM TREVOR WESTON Messages (b. 1967) LUCIANO BERIO Folk Songs for Mezzo-Soprano and 7 Instruments (1925–2003) Black is the colour... I wonder as I wander... Loosin yelav... Rossignolet du bois A la femminisca La donna ideale Ballo Motettu de tristura Malurous qu’o uno fenno Lo fiolaire Azerbaijan love song Makila Kirchner, mezz0-soprano CAMERATA NOVA FLUTE BASSOON VIOLIN CELLO HARP Marcos Ruiz Matthew Pauls Adelya Nartadjieva Haena Lee Minyoung Kwon Miami, Florida Simi Valley, California Tashkent, Uzbekistan Cochrane, Canada Seoul, South Korea Yixiang Wang CLARINET TRUMPET Xi’an, China PERCUSSION Chao-Chih George Julia Bravo Gabriel Elias Chen Hollywood, Florida VIOLA Costache Yunlin, Taiwan Dudley Raine IV Denver, Colorado Lynchburg, Virginia Will Hopkins Dallas, Texas ABOUT THE CONDUCTOR George Manahan is in his 11th season as Director of Orchestral Activities at Manhattan School of Music, as well as Music Director of the American Composers Orchestra and the Portland Opera. He served as Music Director of the New York City Opera for 14 seasons and was hailed for his leadership of the orchestra. He was also Music Director of the Richmond Symphony (VA) for 12 seasons. Recipient of Columbia University’s Ditson Conductor’s Award, Mr. Manahan was also honored by the American Society of Composers and Publishers (ASCAP) for his “career-long advocacy for American composers and the music of our time.” His Carnegie Hall performance of Samuel Barber’s Antony and Cleopatra was hailed by audiences and critics alike. -

Msm Chamber Sinfonia and Chamber Choir

MSM CHAMBER SINFONIA AND CHAMBER CHOIR Jane Glover, Conductor Kent Tritle, Chorus Master Julie Nah Kyung Lee (BM ’18, MM ’20), flute Brittany Nickell (MM ’15, PS ’16), soprano Briana Elyse Hunter (MM ’12), mezzo-soprano Philippe L’Esperance (MM ’17), tenor Kidon Choi (MM ’15), baritone FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 15, 2019 | 7:30 PM NEIDORFF-KARPATI HALL FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 15, 2019 | 7:30 PM NEIDORFF-KARPATI HALL MSM CHAMBER SINFONIA AND JaneCHAMBER Glover, Conductor CHOIR Kent Tritle, Chorus Master Julie Nah Kyung Lee (BM ’18, MM ’20), flute Brittany Nickell (MM ’15, PS ’16), soprano Briana Elyse Hunter (MM ’12), mezzo-soprano Philippe L’Esperance (MM ’17), tenor Kidon Choi (MM ’15), baritone PROGRAM ADOLPHUS Epitaph for a Man Who Dreamed HAILSTORK In Memoriam: Martin Luther King, Jr. (BM ’63, MM ’65) (b. 1941) CARL NIELSEN Flute Concerto (1865–1931) Allegro moderato Allegretto Julie Nah Kyung Lee, flute Intermission LUDWIG VAN Mass in C Major, Op. 86 BEETHOVEN Kyrie (1770–1827) Gloria Credo Sanctus Agnus Dei Brittany Nickell, soprano Briana Elyse Hunter, mezzo-soprano Philippe L’Esperance, tenor Kidon Choi, baritone Kidon Choi appears by kind permission of the Metropolitan Opera Lindemann Young Artist Development Program. PROGRAM NOTES Epitaph for a Man Who Dreamed In Memoriam: Martin Luther King, Jr. Adolphus Hailstork Growing up in Albany, New York, Hailstork received his first musical training as a chorister and, after showing an aptitude for music in state testing, he received free violin lessons in fourth grade, later switching to piano and organ. He loved to improvise, which led him to composing. -

A Stylistic Analysis of Francis Ford Coppola's Trilogy Movie the Godfather

مجلة ) - (Hebron University Research Journal-B (Humanities جامعة الخليل للبحوث- ب (العلوم االنسانيه Volume 15 Issue 2 Article 9 2020 A Stylistic Analysis of Francis Ford Coppola’s trilogy Movie the Godfather Saja Najjar Hebron University, [email protected] Nimer Abuzahra Hebron University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.aaru.edu.jo/hujr_b Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Najjar, Saja and Abuzahra, Nimer (2020) "A Stylistic Analysis of Francis Ford Coppola’s trilogy Movie the مجلة جامعة الخليل للبحوث- ب (العلوم ) - (Godfather," Hebron University Research Journal-B (Humanities .Vol. 15 : Iss. 2 , Article 9 :االنسانيه Available at: https://digitalcommons.aaru.edu.jo/hujr_b/vol15/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Arab Journals Platform. It has been accepted for by an مجلة جامعة الخليل للبحوث- ب (العلوم االنسانيه) - (inclusion in Hebron University Research Journal-B (Humanities authorized editor. The journal is hosted on Digital Commons, an Elsevier platform. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Najjar and Abuzahra: A Stylistic Analysis of Francis Ford Coppola’s trilogy Movie the Hebron University Research Journal( B) H.U.R.J. is available online at Vol.(15), No.(2), pp.(208-236), 2020 http://www.hebron.edu/journal A Stylistic Analysis of Francis Ford Coppola’s trilogy Movie the Godfather Saja Khalil Najjar, Dr. Nimer Abuzahra Hebron University, Department of English Received: 31/12/2019- Accepted: 27/2/2020 Abstract: Crime movies, according to the IMDbwebsite, are the most popular film's genre in Hollywood.