Plungers and Productivity: a Student Artist's Survival Guide to Multi-Tasking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: the Musical Katherine B

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2016 "Can We Do A Happy Musical Next Time?": Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: The Musical Katherine B. Marcus Reker Scripps College Recommended Citation Marcus Reker, Katherine B., ""Can We Do A Happy Musical Next Time?": Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: The usicalM " (2016). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 876. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/876 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “CAN WE DO A HAPPY MUSICAL NEXT TIME?”: NAVIGATING BRECHTIAN TRADITION AND SATIRICAL COMEDY THROUGH HOPE’S EYES IN URINETOWN: THE MUSICAL BY KATHERINE MARCUS REKER “Nothing is more revolting than when an actor pretends not to notice that he has left the level of plain speech and started to sing.” – Bertolt Brecht SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS GIOVANNI ORTEGA ARTHUR HOROWITZ THOMAS LEABHART RONNIE BROSTERMAN APRIL 22, 2016 II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not be possible without the support of the entire Faculty, Staff, and Community of the Pomona College Department of Theatre and Dance. Thank you to Art, Sherry, Betty, Janet, Gio, Tom, Carolyn, and Joyce for teaching and supporting me throughout this process and my time at Scripps College. Thank you, Art, for convincing me to minor and eventually major in this beautiful subject after taking my first theatre class with you my second year here. -

The Maple Shade Arts Council Summer Theatre the MAPLE SHADE Announces Our Summer Children's Show ARTS COUNCIL Once Upon a Mattress PROUDLY PRESENTS

The Maple Shade Arts Council Summer Theatre THE MAPLE SHADE announces our summer children's show ARTS COUNCIL Once Upon A Mattress PROUDLY PRESENTS PERFORMANCES: August 6 @ 7:30PM August 7 @ 7:30PM August 8 @ 2:00PM and 7:30PM Tickets: $10—adults $8—children/senior citizens Visit www.msartscouncil.org to purchase tickets today! For more information about the Summer Theatre program and how to register for next year, email [email protected] Bring in your playbill or ticket to July 10, 11, 12, 17, 18, 19 @ 7:30PM 114-116 E. MAIN ST. receive a 15% discount off your Maple Shade High School MAPLE SHADE, NJ 08052 bill. Valid before or after the (856)779-8003 performances on July 10-12 and Auditorium 17-19. Not valid with any other coupons, offers, or discounts. 2014 Sponsors OUR MISSION STATEMENT The Maple Shade Arts Council wishes to express our sincere gratitude to the many sponsors to our organization. The Maple Shade Arts Council is a non-profit organization We appreciate your support of the Arts Council. comprised of educators, parents, and community members whose objective is to provide artistic programs and events that will be entertaining, educational, and inspirational for the community. The Arts Council's programming emphasizes theatrical productions and workshops, yet also includes programming for the fine and performing arts. Maple Shade Arts Council Executive Board 2014 President Michael Melvin Vice President Jillian Starr-Renbjor Secretary AnnMarie Underwood Treasurer Matthew Maerten Publicity Director Rose Young Fundraising Director Debra Kleine Fine Arts Director Nancy Haddon *ALL CONCESSIONS WILL BE SOLD PRIOR TO THE SHOW BETWEEN 6:45PM-7:25PM—THERE WILL ONLY BE A BRIEF 10 MINUTE BATHROOM/SNACK BREAK AT INTERMISSION. -

A Career Overview 2019

ELAINE PAIGE A CAREER OVERVIEW 2019 Official Website: www.elainepaige.com Twitter: @elaine_paige THEATRE: Date Production Role Theatre 1968–1970 Hair Member of the Tribe Shaftesbury Theatre (London) 1973–1974 Grease Sandy New London Theatre (London) 1974–1975 Billy Rita Theatre Royal, Drury Lane (London) 1976–1977 The Boyfriend Maisie Haymarket Theatre (Leicester) 1978–1980 Evita Eva Perón Prince Edward Theatre (London) 1981–1982 Cats Grizabella New London Theatre (London) 1983–1984 Abbacadabra Miss Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith Williams/Carabosse (London) 1986–1987 Chess Florence Vassy Prince Edward Theatre (London) 1989–1990 Anything Goes Reno Sweeney Prince Edward Theatre (London) 1993–1994 Piaf Édith Piaf Piccadilly Theatre (London) 1994, 1995- Sunset Boulevard Norma Desmond Adelphi Theatre (London) & then 1996, 1996– Minskoff Theatre (New York) 19981997 The Misanthrope Célimène Peter Hall Company, Piccadilly Theatre (London) 2000–2001 The King And I Anna Leonowens London Palladium (London) 2003 Where There's A Will Angèle Yvonne Arnaud Theatre (Guildford) & then the Theatre Royal 2004 Sweeney Todd – The Demon Mrs Lovett New York City Opera (New York)(Brighton) Barber Of Fleet Street 2007 The Drowsy Chaperone The Drowsy Novello Theatre (London) Chaperone/Beatrice 2011-12 Follies Carlotta CampionStockwell Kennedy Centre (Washington DC) Marquis Theatre, (New York) 2017-18 Dick Whttington Queen Rat LondoAhmansen Theatre (Los Angeles)n Palladium Theatre OTHER EARLY THEATRE ROLES: The Roar Of The Greasepaint - The Smell Of The Crowd (UK Tour) -

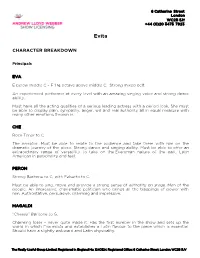

Character Breakdown

6 Catherine Street London WC2B 5JY +44 (0)20 3475 7923 Evita CHARACTER BREAKDOWN Principals EVA E below middle C – F 1 ½ octave above middle C. Strong mixed belt. An experienced performer at every level with an amazing singing voice and strong dance ability. Must have all the acting qualities of a serious leading actress with a period look. She must be able to display pain, sympathy, anger, wit and real authority all in equal measure with many other emotions thrown in. CHE Rock Tenor to C The narrator. Must be able to relate to the audience and take them with him on the dramatic journey of the piece. Strong dance and singing ability. Must be able to offer an extraordinary range of versatility to take on the Everyman nature of the part. Latin American in personality and feel. PERON Strong Baritone to G, with Falsetto to C. Must be able to sing, move and provide a strong sense of authority on stage. Man of the people. An impressive, charismatic politician who brings all the trappings of power with him. Authoritative, persuasive, charming and impressive. MAGALDI “Cheesy” Baritone to G. Charming loser – never quite made it. Has the first number in the show and sets up the world in which Eva exists and establishes a Latin flavour to the piece which is essential. Should have a slightly awkward and Latin physicality. The Really Useful Group Limited. Registered in England No. 1240524. Registered Office: 6 Catherine Street, London WC2B 5JY 6 Catherine Street London WC2B 5JY +44 (0)20 3475 7923 MISTRESS Light contemporary mix to E Beautiful. -

Nominations/2006 – 2007 Tamy Awards

NOMINATIONS/2018 – 2019 TAMY AWARDS Theatre at the Mount High School Musical Theatre Competition BEST OVERALL PRODUCTION (Large School Division) Fiddler on the Roof – Bedford High School Fiddler on the Roof – Chelmsford High School Urinetown – Leominster High School Seussical – Shrewsbury High School Godspell – Tewksbury High School Curtains – Wachusett Regional High School BEST OVERALL PRODUCTION (Small School Division) Chicago – Auburn High School Mary Poppins – Hudson High School Young Frankenstein – Montachusett Regional Technical High School Evita – Oakmont Regional High School Les Miserables – Tyngsborough High School BEST ACTOR Derek Brigham (Billy) – Chicago (Auburn) Eran Zelixon (Tevye) – Fiddler on the Roof (Bedford) Philip Ferdinand (Tevye) – Fiddler on the Roof (Chelmsford) Max Charbonneau (Che) – Evita (Oakmont) Jared LeMay (Jean Valjean) – Les Miserables (Tyngsborough) Chris Van Liew (Frank Cioffi) – Curtains (Wachusett) BEST ACTRESS Becca Ford (Esmerelda) – Hunchback of Notre Dame (Acton-Boxborough) Lily Usherwood (Mary Poppins) – Mary Poppins (Hudson) Abby Waterhouse (Hope Cladwell) – Urinetown (Leominster) Mary Mahoney (Young Eva Duarte) – Evita (Oakmont) Belle McNamara (Georgia Hendricks) – Curtains (Wachusett) Hannah Friend (Carmen Bernstein) – Curtains (Wachusett) BEST SUPPORTING ACTOR Matthew Grega (Clopin Trouillefou) – Hunchback of Notre Dame (Acton- Boxborough) Sean Campbell (Amos) – Chicago (Auburn) Ben Woodward (Perchik) – Fiddler on the Roof (Bedford)) Connor Mangan (Judas) – Godspell -

Hastings Point 'Under Threat'

THE TWEED SHIRE National Volume 1 #11 Thursday, November 6, 2008 Advertising and news enquiries: Recycling Phone: (02) 6672 2280 Fax: (02) 6672 4933 Week [email protected] [email protected] November 10-16 See pages 12-13 www.tweedecho.com.au LOCAL & INDEPENDENT Hastings Point ‘under threat’ Ken Sapwell part ‘ to provide more definable plan- ning controls.’ Hastings Point residents have hit an- But a bid by deputy mayor Barry other hurdle in their long battle to Longland and Greens councillor Katie secure a two-storey height limit and Milne to bring in the blanket controls density controls to protect their small was torpedoed by other councillors village from overdevelopment and who called for a closed-door work- avert what they see as an ecological shop to obtain more information. disaster. Cr Milne said the community had In a surprise decision, councillors been through ‘hell and high-water’ last week decided against adopting a over several years trying to stop over- development control plan (DCP) to development and further delays in limit building heights and densities in bringing in the DCP would open the the village until they were briefed on door to more DA’s and subsequent the history of the long-running saga. court cases. Residents now fear the delay leaves But Cr Warren Polglase success- the door open for a rush of appli- fully moved to defer a decision, saying cations for residential flat buildings, there were conflicting views about including a revised application for a the proposed DCP and councillors seven-unit project in Young Street needed a detailed briefing about the which they stopped after going to the new controls which had the potential Joe’s incredible journey takes off Land and Environment Court three to spark a ‘civil war.’ months ago. -

Lyrics by Tim Rice Music by Andrew Lloyd Webber Directed by Rob Ruggiero

2018–2019 SEASON EVITA LYRICS BY TIM RICE MUSIC BY ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER DIRECTED BY ROB RUGGIERO CONTENTS 2 The 411 3 A/S/L, HTH 4 FYI 6 B4U 7 IRL 8 RBTL At The Rep, we know HOW TO BE THE BEST AUDIENCE EVER! that life moves fast— TAKE YOUR SEAT okay, really fast. But An usher will seat your class as a group, and often we have we also know that a full house with no seats to spare, so be sure to stick with some things are your school until you have been shown your section in the worth slowing down theatre. for. We believe that live theatre is one of those pit stops worth making and are excited that you are going to stop SILENCE IS GOLDEN by for a show. To help you get the most bang for your buck, Before the performance begins, be sure to turn off your cell we have put together WU? @ THE REP—an IM guide that will phone and watch alarms. If you need to talk or text during give you everything you need to know to get at the top of your intermission, don’t forget to click off before the show theatergoing game—fast. You’ll find character descriptions resumes. (A/S/L), a plot summary (FYI), biographical information (F2F), BREAK TIME historical context (B4U), and other bits and pieces (HTH). Most This performance includes an intermission, at which time importantly, we’ll have some ideas about what this all means you can visit the restrooms in the lobby. -

CAGNEY (Currently at the Westside Theatre, NYC), C.S

Bill Castellino Director BILL CASTELLINO has directed many world premieres: CAGNEY (currently at the Westside Theatre, NYC), C.S. Lewis’ THE GREAT DIVORCE (Off-Broadway & National Tour), GRUMPY OLD MEN (The Royal Manitoba Theatre Center) starring John Rubinstein, John Schuck, Susan Anton, JOLSON AT THE WINTER GARDEN starring Mike Burstein in FL and LA, the award-winning DR. RADIO (Florida Studio Theatre), LIZZIE BORDEN (Goodspeed Opera House), HEARTBEATS (The Old Globe, Goodspeed Opera House, Cleveland and Pasadena Playhouses, FL, National Tour), MIKLAT (Florida Stage), SOME KIND OF WONDERFUL, FISHWRAP (Adirondack Theatre Festival), HOUSE DIVIDED by Grammy winner Mike Reid (Tennessee Rep), SINGING WEATHERMAN starring Ron Holgate, HAPPY HOLIDAYS (Pasadena Playhouse), PRESIDENTS starring Rich Little (National Tour), HOW TO BE AN AMERICAN (York, NYC), CRASH CLUB, SOULMATES (Florida Studio Theatre), ANOTHER SUMMER (the musical of ON GOLDEN POND), BREATHE by Dan Martin and Michael Biello, Elizabeth Swados’ WE ARE NOT STRANGERS, Loren Paul Caplin's A SUBJECT OF CHILDHOOD (WPA), WHY DO FOOLS FALL IN LOVE (West Side Arts), COCONUTS AND SUICIDE (produced in L.A. by the Mount Company), THEATRE SMASH (San Diego), and CITY MUZIK (co-authored with Mr. Caplin) in Boston. At the NY Shakespeare Festival, Mr. Castellino directed and choreographed FANTASMA (in the Festival Latino) and staged and choreographed Swados' JONAH. On television, Castellino directed and choreographed STOP THE WORLD, I WANT TO GET OFF, starring Peter Scolari and Stephanie Zimbalist for A&E, wrote, directed, and choreographed BELL ARIA filmed at the Venetian in LV for PBS, THE PRESIDENTS starring Rich Little for PBS, and choreographed RAP MASTER RONNIE for Cinemax. -

Who's Who in the Cast

WHO’S WHO IN THE CAST ROBERT PETKOFF (Bruce). Broadway: All The Way with Bryan Cranston, Anything Goes, Ragtime, Spamalot, Fiddler On The Roof and Epic Proportions. London: The Royal Family with Dame Judi Dench and Tantalus. Regional: Sweeney Todd, Hamlet, Troilus & Cressida, Follies, Romeo & Juliet, Compleat Female Stage Beauty and The Importance Of Being Earnest. Film: Irrational Man, Vice Versa, Milk and Money, Gameday. TV: Elementary, Forever, Law and Order: SVU, The Good Wife and more. Robert is an award-winning audiobook narrator. SUSAN MONIZ (Helen). Broadway: Grease – Sandy & Rizzo. Regional: Follies – Sally (Chicago Shakespeare Theater); October Sky –Elsie (world premier); Peggy Sue Got Married – Peggy (world premier); Kismet (Joseph Jefferson award); Into the Woods, 9 to 5, Carousel, (Marriott Theatre); The Merry Widow, The Sound Of Music, (Chicago Lyric Opera); Hot Mikado (Ford’s Theatre); Phantom, Chitty- Chitty Bang-Bang (Fulton Theatre); Shadowlands, The Spitfire Grill, (Provision Theatre); Evita, BIG, (Drury Lane Theatre). TV: Chicago PD; Romance, Romance (A&E). KATE SHINDLE (Alison). Broadway: Legally Blonde (Vivienne), Cabaret (Sally Bowles), Wonderland (Hatter), Jekyll & Hyde. Elsewhere: Rapture, Blister, Burn (Catherine), After the Fall (Maggie), Restoration, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Gypsy, Into the Woods, The Last Five Years, First Lady Suite, The Mousetrap. Film/TV: Lucky Stiff, SVU, White Collar, Gossip Girl, The Stepford Wives, Capote. Kate is a longtime activist, author of Being Miss America: Behind the Rhinestone Curtain and President of Actors’ Equity Association. twitter.com/AEApresident ABBY CORRIGAN (Middle Alison). Stage: Cabaret, A Chorus Line (TCS); Shrek (Blumey award), In The Heights, Peter Pan, Rent (NWSA); Next to Normal (QCTC); Film/TV: Headed South For Christmas (Painted Horse), A Smile As Big As The Moon (Hallmark), Homeland (HBO), Rectify (Sundance), Banshee (Cinemax). -

Andrew Lloyd Webber's Musicals

MASARYK UNIVERSITY Faculty of Education Department of English Language and Literature ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER’S MUSICALS Diploma Thesis Brno 2009 Radka Adamová Supervisor: Mgr. Lucie Podroužková, PhD. 1 BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ENTRY Adamová, Radka. Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Musicals Brno: Masaryk University, Faculty of Education, Department of English Language and Literature, 2007. Diploma thesis supervisor Mgr. Lucie Podroužková, Ph. D. ANNOTATION This diploma thesis deals with British musical composer Andrew Lloyd Webber and his works. The first part of the thesis introduces Lloyd Webber’s biography, his close collaborators as well as his production company the Really Useful Group and description of all his works. The main part of the thesis is aimed at his musicals Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat and Jesus Christ Superstar , rather their origin and development, the main plot and their main characters that have many things in common. Both these musicals are based on topics from the Bible. The thesis also deals with the librettos and their translation into Czech. ANOTACE Diplomová práce se zabývá britským hudebním skladatelem Andrew Lloyd Webberem a jeho díly. První část práce seznamuje s Lloyd Webberovým životopisem, jeho blízkými spolupracovníky, stejně jako s jeho produkční společností Really Useful Group a popisem všech jeho děl. Hlavní část práce je zaměřena na muzikály Josef a jeho úžasný pestrobarevný plášť a Jesus Christ Superstar , přesněji řečeno jejich vznik a vývoj, hlavní dějovou linii a jejich hlavní postavy, které mají mnoho společného. Oba tyto muzikály jsou založeny na příbězích z Bible. Práce se také zabýva librety obou muzikálů a jejich překladem do češtiny. 2 I declare that I have worked on this thesis on my own and used only the sources listed in the Bibliography. -

Teacher Resource Guide Falsettos.Titlepage.09272016 Title Page As of 091516.Qxd 9/27/16 1:51 PM Page 1

Teacher Resource Guide Falsettos.TitlePage.09272016_Title Page as of 091516.qxd 9/27/16 1:51 PM Page 1 Falsettos Teacher Resource Guide by Nicole Kempskie MJODPMO!DFOUFS!UIFBUFS André Bishop Producing Artistic Director Adam Siegel Hattie K. Jutagir Managing Director Executive Director of Development & Planning in association with Jujamcyn Theaters presents Music and Lyrics by William Finn Book by William Finn and James Lapine with (in alphabetical order) Stephanie J. Block Christian Borle Andrew Rannells Anthony Rosenthal Tracie Thoms Brandon Uranowitz Betsy Wolfe Sets Costumes Lighting Sound David Rockwell Jennifer Caprio Jeff Croiter Dan Moses Schreier Music Direction Orchestrations Vadim Feichtner Michael Starobin Casting Mindich Chair Tara Rubin, CSA Production Stage Manager Musical Theater Associate Producer Eric Woodall, CSA Scott Taylor Rollison Ira Weitzman General Manager Production Manager Director of Marketing General Press Agent Jessica Niebanck Paul Smithyman Linda Mason Ross Philip Rinaldi Choreography Spencer Liff Directed by James Lapine Lincoln Center Theater is grateful to the Stacey and Eric Mindich Fund for Musical Theater at LCT for their leading support of this production. LCT also thanks these generous contributors to FALSETTOS: The SHS Foundation l The Blanche and Irving Laurie Foundation The Kors Le Pere Foundation l Ted Snowdon The Ted and Mary Jo Shen Charitable Gift Fund American Airlines is the Official Airline of Lincoln Center Theater. Playwrights Horizons, Inc., New York City, produced MARCH OF THE FALSETTOS Off-Broadway in 1981 and FALSETTOLAND Off-Broadway in 1990. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 1 THE MUSICAL . 2 The Story . 2 The Characters . 4 The Writers . 5 Classroom Activities . -

HBL 2021 COURSEBOOK Week

LIVE DIGITAL WEEKEND day 1 Sat jan 30 ramone owens BROADWAY'S BEETLEJUICE, MOTOWN THE MUSICAL rodrick covington BROADWAY’S ONCE ON THIS ISLAND, FOUNDER OF CORE RHYTHM FITNESS leandra ellis gaston BROADWAY'S TINA: THE TINA TURNER MUSICAL joshua burrage BDISNEY'S NEWSIES ON BROADWAY ramone owens BROADWAY'S BEETLEJUICE, MOTOWN THE MUSICAL max clayton ahmad simmons BROADWAY'S MOULIN ROUGE, BROADWAY'S WEST SIDE HELLO DOLLY! STORY, HADESTOWN Eva Noblezada BROADWAY'S MISS SAIGON, desi oakley HADESTOWN BROADWAY’S WICKED, NATIONAL TOUR OF WAITRESS benton whitley harold lewter BROADWAY TALENT STEWART/WHITLEY CASTING MANAGER, CLA PARTNERS cody renard RICHARD BROADWAY STAGE MANAGER erika henningsen BROADWAY'S MEAN GIRLS, FLYING OVER SUNSET ROBERT HARTWELL FOUNDER + ARTISTIC DIRECTOR OF THE BROADWAY COLLECTIVE + FULL TBC TEAM day 2 sun jan 31 zakiya young brandon logan BROADWAY'S THE LITTLE BROADWAY'S MERMAID, STICK FLY BOOK OF MORMON andy jones BROADWAY'S CINDERELLA, CATS sydney morton BROADWAY'S AMERICAN PSYCHO, MOTOWN erika dorfler BROADWAY’S THE GREAT COMET, MEMPHIS laura osnes BROADWAY'S CINDERELLA, BONNIE + CLYDE solea pfeiffer NATIONAL TOUR OF HAMILTON, SONGS FOR A NEW WORLD, EVITA (CITY CENTER) ben tyler cook BROADWAY'S NEWSIES, MEAN GIRLS tyler mckenzie cynthia westphal BROADWAY’S HAMILTON, BROADWAY’S COME FROM AWAY, LECTURER OF DANCE + ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF MUSICAL THEATRE AT PENN MUSICAL THEATRE AT THE STATE UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN julio matos katie ann BROADWAY’S FOSSE, DIRECTOR OF MUSIC THEATRE JOHANNIGMAN AT ELON UNIVERSITY NATIONAL TOUR OF OLIVER!, ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF MUSICAL THEATRE AT CCM andy jones ramone owens BROADWAY'S BROADWAY'S BEETLEJUICE, CINDERELLA, CATS MOTOWN THE MUSICAL ROBERT HARTWELL FOUNDER + ARTISTIC DIRECTOR OF THE BROADWAY COLLECTIVE + FULL TBC TEAM.