From Eros to Eternity: Piccadilly's Stone Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Operator's Story Appendix

Railway and Transport Strategy Centre The Operator’s Story Appendix: London’s Story © World Bank / Imperial College London Property of the World Bank and the RTSC at Imperial College London Community of Metros CoMET The Operator’s Story: Notes from London Case Study Interviews February 2017 Purpose The purpose of this document is to provide a permanent record for the researchers of what was said by people interviewed for ‘The Operator’s Story’ in London. These notes are based upon 14 meetings between 6th-9th October 2015, plus one further meeting in January 2016. This document will ultimately form an appendix to the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’ piece Although the findings have been arranged and structured by Imperial College London, they remain a collation of thoughts and statements from interviewees, and continue to be the opinions of those interviewed, rather than of Imperial College London. Prefacing the notes is a summary of Imperial College’s key findings based on comments made, which will be drawn out further in the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’. Method This content is a collation in note form of views expressed in the interviews that were conducted for this study. Comments are not attributed to specific individuals, as agreed with the interviewees and TfL. However, in some cases it is noted that a comment was made by an individual external not employed by TfL (‘external commentator’), where it is appropriate to draw a distinction between views expressed by TfL themselves and those expressed about their organisation. -

Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--History History 2016 Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945 Danielle K. Dodson University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.339 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dodson, Danielle K., "Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945" (2016). Theses and Dissertations--History. 40. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/history_etds/40 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--History by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

12 October 2011 Thirty-Fourth Mayor's Report to the Assembly

London Assembly MQT – 12 October 2011 Thirty-fourth Mayor’s Report to the Assembly This is my thirty-fourth report to the Assembly, fulfilling my duty under Section 45 of the Greater London Authority Act 1999. It covers the period 1 September to 28 September 2011. Executive Summary Bernard Hogan-Howe appointed as the new Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police. On 12 September, after interviewing the final four candidates with the Home Secretary, Bernard Hogan-Howe was appointed the new Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police. Londoners deserve strong and dynamic leadership at the helm of the country’s largest and most industrious police force, and I’m pleased to welcome the appointment of Bernard as the man who will deliver the firm, strategic lead our great city needs. Improving the Management of Disruptive Roadworks On 21 September, I announced a new onslaught on disruptive roadworks on London's streets by asking Londoners to "name and shame" those companies who blight London with disruptive or neglected roadworks, causing hours of unnecessary frustration to journeys every day. I urged Londoners to use a new reporting system to tell Transport for London (TfL) when roadworks are not up to scratch so they can take action with the relevant organisations and get things moving again. To help Londoners report disruptive or badly managed roadworks, TfL and I have updated the 'Reportit' system on the TfL website, to allow people to identify and report issues quicker. By visiting www.tfl.gov.uk/roadworks, or by tweeting @report_it with the hashtag #roadworks, complaints can be sent directly to the highway authority responsible, ensuring that direct and swift action can be taken. -

Download Directions

Directions Spectrum, 15 Stratton Street, Mayfair, London, W1J 8LQ. United Kingdom. By London Underground Spectrum’s office is a one minute walk from Green Park tube station, which can be accessed directly from the Piccadilly, Victoria and Jubilee lines. Take the right hand exit from the tube station onto Stratton Street (opposite Langan’s Brasserie) and turn right. As Stratton Street bears round to the right, Spectrum’s office at 15 Stratton Street is located in the left hand corner. There is a large green flag hanging outside the building with the signage “Green Park House”. From London mainline train stations Waterloo: Take the Jubilee line (north) to Green Park. Paddington: Take the Bakerloo line (south) to Oxford Circus. Take the Victoria line (south) to Green Park. Euston/Kings Cross/St. Pancras: Take the Victoria line (south) to Green Park. Victoria: Take the Victoria line (north) to Green Park. From London airports Heathrow Airport: take Heathrow Express train (20 minutes) to Paddington station. Take the Bakerloo line (south) to Oxford Circus. Take the Victoria line (south) to Green Park. City Airport: take Docklands Light Railway (DLR) to Canning Town (7 minutes). Take Jubilee line to Green Park (18 minutes). Gatwick Airport: take Gatwick Express train (30 minutes) to Victoria station. Take the Victoria line (north) one stop to Green Park (2 minutes). Parking There are parking meters located around Berkeley Square. The nearest NCP car park is located in Carrington Street. If arriving by private car, please be aware that the office is within the Congestion Charging Zone. For further information, please visit: www.cclondon.com . -

Hardrockcafe.Com Piccadilly Circus | Criterion Building

rome Piccadilly Circus Piccadilly Circus | Criterion Building | 225-229 Piccadilly, London W1J 9HR | + 44 20 7287 4600 #HardRockCafe | HardRockCafe.com ©2019 Hard Rock International (USA), Inc. All rights reserved. HARD ROCK CAFE PICCADILLY CIRCUS Hard Rock Cafe Piccadilly is not only a restaurant; it is also a great venue for events! Located in the heart of Piccadilly Circus, London, our European Flagship cafe has changed the face of dining & entertainment in the capital. Combining the eclectic vibe of Piccadilly Circus with the rock and roll edge of the Hard Rock brand, the state-of-the-art cafe pays tribute to the Criterion Building’s prestigious heritage and unbeatable West End location. Hard Rock Cafe Piccadilly Circus is the ultimate venue for innovative food, signature cocktails, amazing music and one-of-a- kind memorabilia from decades of music history – your event will truly be a unique experience that Rocks! • FULL VENUE HIRE • TEAM BUILDING EVENTS • PRIVATE LUNCHES & DINNERS • PRODUCT LAUNCHES & PREMIERES • CORPORATE EVENTS & MEETINGS • GALA DINNERS • CHRISTMAS PARTIES • COCKTAIL PARTIES CUSTOMISED EVENTS From Launch Events to Corporate Parties, we can do it all! With a capacity of 650 people, a stage perfect for live music or speeches, VIP booths, 360° bar and full AV capabilities, the possibilities are endless. Catering, entertainment and authentic event merchandise can be customised to complement every event. To add a wow factor, put your logo in an ice sculpture, or treat your attendees like Rock Stars with event-specific lanyards. Take a bite of rock and roll-inspired tastes and quench your thirst with authentic cocktails, designed especially for your event: • BESPOKE FOOD STATIONS • CLASSIC HARD ROCK CANAPÉS & BOWL FOOD • BREAKFAST BUFFET OR PLATED OPTIONS • THREE-COURSE SIT-DOWN MEALS • WORKING LUNCHES • COCKTAIL-MAKING CLASSES LEGENDS ROOM A hidden gem in Piccadilly Circus, the Legends Room is an exciting and unique meetings and events space with the spirit of Rock and Roll. -

Trades' Directory. 811

1841.] TRADES' DIRECTORY. 811 SILK &VEL YET MANFRS.-continued. l\Iay William, 132 Bishops~ate without DentJ.30,31,32 Crawfordst.Portmansq Brandon William, 23 Spital square *Nalders, Spall & Co. 41 Cheapside Devy M. 73 Lower Grosvenor street, & Bridges & Camp bell, 19 Friday street N eill & Langlands, 45 Friday street 120 George street, Edinburgh Bridgett Joseph & Co.63 Alderman bury Perry T. W. & Co. 20 Steward st. Spitalfi *Donnon Wm.3.5Garden row, London rd British, IJ-ish, ~· Colonial Silk Go. 10~ Place & Wood, 10 Cateaton street Duthoit & Harris, 77 Bishopsgate within King's arms yard Powell John & Daniel, 1 Milk !'treet t Edgington \Yilliam, 37 Piccadilly Brocklehurst Jno. & Th. 32 & 331\-Iilk st t Price T. Divett, 19 Wilson st. Finsbury Elliot Miss Margt. Anne, 43 Pall mall Brooks Nathaniel, 25 Spital square Ratliffs & Co. 78\Vood st. Cheapside E~·les,Evans,Hands&.Wells,5Ludgatest Brown .Archbd. & Co.ltl Friday st.Chpsi Rawlinson Geo. & Co. 34 King st. City *Garnham Wm. Henry, 30 Red Lion sq *Brown James U. & Co. 3,5 Wood street Reid John & Co. 21 Spital square George & Lambert, 192 Regent street *Brunskill Chas.& Wm.5 Paternostr.rw Relph & Witham, 6 Mitre court, Milk st Green Saml. 7 Lit. Aygyll st.llegent st Brunt Josiah, & Co.12 Milk st. Cheapsi Remington, Mills & Co. 30 Milk street Griffiths & Crick, 1 Chandos street Bullock Wm. & Co. 11 Paternoster row tRobinsonJas.&Wm.3&4Milkst.Chepsid +Hall Hichanl, 29 St. John street Buttre~s J. J. & Son, 36Stewardst.Spital RobinsonJ. & T. 21 to 23 Fort st. Spitalfi *Hamer & Jones, 59 Blackfriars road Buttress John, 15 Spital square Salter J. -

Different Faces of One ‘Idea’ Jean-Yves Blaise, Iwona Dudek

Different faces of one ‘idea’ Jean-Yves Blaise, Iwona Dudek To cite this version: Jean-Yves Blaise, Iwona Dudek. Different faces of one ‘idea’. Architectural transformations on the Market Square in Krakow. A systematic visual catalogue, AFM Publishing House / Oficyna Wydawnicza AFM, 2016, 978-83-65208-47-7. halshs-01951624 HAL Id: halshs-01951624 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01951624 Submitted on 20 Dec 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Architectural transformations on the Market Square in Krakow A systematic visual catalogue Jean-Yves BLAISE Iwona DUDEK Different faces of one ‘idea’ Section three, presents a selection of analogous examples (European public use and commercial buildings) so as to help the reader weigh to which extent the layout of Krakow’s marketplace, as well as its architectures, can be related to other sites. Market Square in Krakow is paradoxically at the same time a typical example of medieval marketplace and a unique site. But the frontline between what is common and what is unique can be seen as “somewhat fuzzy”. Among these examples readers should observe a number of unexpected similarities, as well as sharp contrasts in terms of form, usage and layout of buildings. -

The Burlington Arcade Would Like to Welcome You to a VIP Invitation with One of London’S Luxury Must-See Shopping Destinations

The Burlington Arcade would like to welcome you to a VIP Invitation with one of London’s luxury must-see shopping destinations BEST OF BRITISH SUPERIOR LUXURY SHOPPING SERVICE & England’s oldest and longest shopping BEADLES arcade, open since 1819, The Burlington TOURS Arcade is a true luxury landmark in London. The Burlington Beadles Housing over 40 specialist shops and are the knowledgeable designer brands including Lulu Guinness uniformed guards and Jimmy Choo’s only UK menswear of the Arcade ȂƤǡ since 1819. They vintage watches, bespoke footwear and the conduct pre-booked Ƥ Ǥ historical tours of the Located discreetly between Bond Street Arcade for visitors and and Piccadilly, the Arcade has long been uphold the rules of the favoured by Royalty, celebrities and the arcade which include prohibiting the opening of cream of British society. umbrellas, bicycles and whistling. The only person who has been given permission to whistle in the Arcade is Sir Paul McCartney. HOTEL GUEST BENEFITS ǤǡƤ the details below and hand to the Burlington Beadles when you visit. They will provide you with the Burlington VIP Card. COMPLIMENTARY VIP EXPERIENCES ơ Ǥ Pre-booked at least 24 hours in advance. Ƥǣ ǡ the expert consultants match your personality to a fragrance. This takes 45 minutes and available to 1-6 persons per session. LADURÉE MACAROONS ǣ Group tea tasting sessions at LupondeTea shop can Internationally famed for its macaroons, Ǧ ơ Parisian tearoom Ladurée, lets you rest and Organic Tea Estate. revive whilst enjoying the surroundings of the To Pre-book simply contact Ellen Lewis directly on: beautiful Arcade. -

Bazaars and Bazaar Buildings in Regency and Victorian London’, the Georgian Group Journal, Vol

Kathryn Morrison, ‘Bazaars and Bazaar Buildings in Regency and Victorian London’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XV, 2006, pp. 281–308 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2006 BAZAARS AND BAZAAR BUILDINGS IN REGENCY AND VICTORIAN LONDON KATHRYN A MORRISON INTRODUCTION upper- and middle-class shoppers, they developed ew retail or social historians have researched the the concept of browsing, revelled in display, and Flarge-scale commercial enterprises of the first discovered increasingly inventive and theatrical ways half of the nineteenth century with the same of combining shopping with entertainment. In enthusiasm and depth of analysis that is applied to the devising the ideal setting for this novel shopping department store, a retail format which blossomed in experience they pioneered a form of retail building the second half of the century. This is largely because which provided abundant space and light. Th is type copious documentation and extensive literary of building, admirably suited to a sales system references enable historians to use the department dependent on the exhibition of goods, would find its store – and especially the metropolitan department ultimate expression in department stores such as the store – to explore a broad range of social, economic famous Galeries Lafayette in Paris and Whiteley’s in and gender-specific issues. These include kleptomania, London. labour conditions, and the development of shopping as a leisure activity for upper- and middle-class women. Historical sources relating to early nineteenth- THE PRINCIPLES OF BAZAAR RETAILING century shopping may be relatively sparse and Shortly after the conclusion of the French wars, inaccessible, yet the study of retail innovation in that London acquired its first arcade (Royal Opera period, both in the appearance of shops and stores Arcade) and its first bazaar (Soho Bazaar), providing and in their economic practices, has great potential. -

LONDON Cushman & Wakefield Global Cities Retail Guide

LONDON Cushman & Wakefield Global Cities Retail Guide Cushman & Wakefield | London | 2019 0 For decades London has led the way in terms of innovation, fashion and retail trends. It is the focal location for new retailers seeking representation in the United Kingdom. London plays a key role on the regional, national and international stage. It is a top target destination for international retailers, and has attracted a greater number of international brands than any other city globally. Demand among international retailers remains strong with high profile deals by the likes of Microsoft, Samsung, Peloton, Gentle Monster and Free People. For those adopting a flagship store only strategy, London gives access to the UK market and is also seen as the springboard for store expansion to the rest of Europe. One of the trends to have emerged is the number of retailers upsizing flagship stores in London; these have included Adidas, Asics, Alexander McQueen, Hermès and Next. Another developing trend is the growing number of food markets. Openings planned include Eataly in City of London, Kerb in Seven Dials and Market Halls on Oxford Street. London is the home to 8.85 million people and hosting over 26 million visitors annually, contributing more than £11.2 billion to the local economy. In central London there is limited retail supply LONDON and retailers are showing strong trading performances. OVERVIEW Cushman & Wakefield | London | 2019 1 LONDON KEY RETAIL STREETS & AREAS CENTRAL LONDON MAYFAIR Central London is undoubtedly one of the forefront Mount Street is located in Mayfair about a ten minute walk destinations for international brands, particularly those from Bond Street, and has become a luxury destination for with larger format store requirements. -

139 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

139 bus time schedule & line map 139 Waterloo - Golders Green View In Website Mode The 139 bus line (Waterloo - Golders Green) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Golders Green: 24 hours (2) Waterloo: 24 hours Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 139 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 139 bus arriving. Direction: Golders Green 139 bus Time Schedule 42 stops Golders Green Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 24 hours Monday 24 hours Waterloo Station / Tenison Way (J) Whichcote Street, London Tuesday 24 hours Waterloo Bridge / South Bank (P) Wednesday 24 hours 1 Charlie Chaplin Walk, London Thursday 24 hours Lancaster Place (T) Friday 24 hours Lancaster Place, London Saturday 24 hours Savoy Street (U) 105-108 Strand, London Bedford Street (J) 60-64 Strand, London 139 bus Info Direction: Golders Green Charing Cross Station (H) Stops: 42 Duncannon Street, London Trip Duration: 62 min Line Summary: Waterloo Station / Tenison Way (J), Trafalgar Square (T) Waterloo Bridge / South Bank (P), Lancaster Place Cockspur Street, London (T), Savoy Street (U), Bedford Street (J), Charing Cross Station (H), Trafalgar Square (T), Regent Regent Street / St James's (Z) Street / St James's (Z), Piccadilly Circus (E), Beak 11 Lower Regent Street, London Street / Hamleys Toy Store (L), Oxford Street / John Lewis (OR), Selfridges (BX), Orchard Street / Piccadilly Circus (E) Selfridges (BA), Portman Square (Y), York Street (F), 83-97 Regent Street, London Baker Street Station (C), Park Road/ Ivor Place (X), -

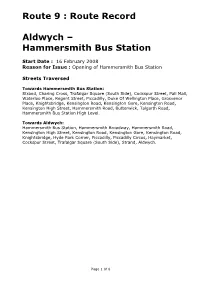

Hammersmith Bus Station

Route 9 : Route Record Aldwych – Hammersmith Bus Station Start Date : 16 February 2008 Reason for Issue : Opening of Hammersmith Bus Station Streets Traversed Towards Hammersmith Bus Station: Strand, Charing Cross, Trafalgar Square (South Side), Cockspur Street, Pall Mall, Waterloo Place, Regent Street, Piccadilly, Duke Of Wellington Place, Grosvenor Place, Knightsbridge, Kensington Road, Kensington Gore, Kensington Road, Kensington High Street, Hammersmith Road, Butterwick, Talgarth Road, Hammersmith Bus Station High Level. Towards Aldwych: Hammersmith Bus Station, Hammersmith Broadway, Hammersmith Road, Kensington High Street, Kensington Road, Kensington Gore, Kensington Road, Knightsbridge, Hyde Park Corner, Piccadilly, Piccadilly Circus, Haymarket, Cockspur Street, Trafalgar Square (South Side), Strand, Aldwych. Page 1 of 6 Stands And Turning Points ALDWYCH, EAST ARM Public offside stand for 6 buses on south side of Aldwych (east arm) commencing 10 metres west of Melbourne Place and extending 67 metres west. Overflow public stand for 3 buses on south side of Strand commencing 10 metres east of Surrey Street and extending 36 metres east. Buses proceed from Aldwych direct to stand, departing via Aldwych to Strand. Set down in Aldwych, at Stop E and pick up in Strand, at Stop R. AVAILABILITY: At any time. OPERATING RESTRICTIONS: No more than 3 buses on Route 9 should be scheduled to stand at any one time. MEAL RELIEFS: No meal relief vehicles to stand at any time. FERRY VEHICLES: No ferry vehicles to park on stand at any time. DISPLAY: Aldwych. OTHER INFORMATION: Stand available for 2 one-person operated vehicles and 1 two-person operated vehicle Toilet facilities available (24 hours). TRAFALGAR SQUARE (from Hammersmith Bus Station) Buses proceed from Cockspur Street via Trafalgar Square (South Side), Charing Cross and Trafalgar Square (South Side) departing to Cockspur Street.