King, Lucia (2012) Performance on Screen in India: Methods and Relationships in Non‐Fiction Film Production, 1991‐2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

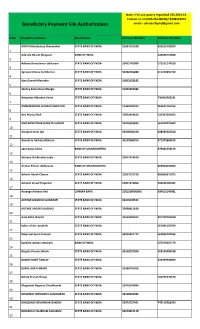

Beneficiary Payment File Authorization Email:- [email protected]

Note:- For any querry regardind CSS 2013-14 Contact us on (020-26126939)/ 8308318919 Beneficiary Payment File Authorization email:- [email protected] S.No Beneficiary Name Bank Name Account Number Aadhaar Number AARTI Mahadeorao Shendurkar STATE BANK OF INDIA 31957537638 659252453204 1 Adamile Bharat Bhagwat BANK OF INDIA 243096723824 2 Adhane Rameshwar Sakharam STATE BANK OF INDIA 33451742999 572551174530 3 Agrawal Antara Sunilkumar STATE BANK OF INDIA 33290256080 311232832732 4 Ajay Ganesh Maturkar STATE BANK OF INDIA 31852633182 5 Akshay Rameshrao Mangle STATE BANK OF INDIA 31904299582 6 Ambarkar Abhishek Vinod STATE BANK OF INDIA 740900562181 7 AMBEWADKAR GOURAV NARAYAN STATE BANK OF INDIA 11365269433 964641761762 8 Ami Manoj Shah STATE BANK OF INDIA 33052414428 226307092832 9 AMILKANTHWAR SHWETA SUDHIR STATE BANK OF INDIA 33415593824 561010421602 10 Aniapure Arun Ajit STATE BANK OF INDIA 33448582440 928583923410 11 Annadate Akshata Mahavir STATE BANK OF INDIA 33135360910 971373889676 12 apar pooja fakira BANK OF MAHARASHTRA 979081533129 13 Archana Shrikrushna Jayle STATE BANK OF INDIA 32047374678 14 Arvikar Pritam Uddhavrao BANK OF MAHARASHTRA 883964656660 15 Ashvini Harish Chavan STATE BANK OF INDIA 31957537729 995866871075 16 Ashwini Vinod Hingankar STATE BANK OF INDIA 32047374850 450533195402 17 Aurange Archana Anil CANARA BANK 2581108006866 999613149981 18 AUTADE MADHURI GANAPATI STATE BANK OF INDIA 33446440532 19 AUTADE SAGAR VILASRAO STATE BANK OF INDIA 33098812108 20 Aute Rohit Sharad STATE BANK OF INDIA 33150350072 -

Ultranationalism: a Proposal for a Quiet Withdrawal

I developed an early suspicion of any form of nationalism courtesy of a geography teacher and an imaginary cricket game. As the only student of Chinese origin in a high school in Bangalore, I was asked by my teacher in a benign voice who I would support if India and China played a match. Aside from the ridiculousness of the question 01/05 (China does not even play cricket), the dubious intent behind it was rather clear, even to a teenager. Still, I dutifully replied, “Sir, I will support India,” for which I received a gratified smile and a pat on the head. I was offended less by the crude attempt by someone in power to force a kid to prove his patriotism, than by the outright silliness of the game. If all it took to Lawrence Liang establish the euphoric security of nationalism was that simple answer, I figured there must be something drastically wrong with the question. I Ultranationalism: was left, however, with an uneasy feeling (one that has persisted through the years), not A Proposal for a because I had given a false answer but because I had been forced to answer a false question. The Quiet answer made pragmatic sense in a schoolboy way (you don’t want to piss off someone who is going to be marking your papers), and I hadn’t Withdrawal read King Lear yet to know that the only appropriate response to the question should have been silence. If Cordelia refuses to participate in Lear’s competition of affective intimacy, it is not just the truth, but also the distasteful aesthetics of her sister’s excessive declarations of love, that motivates her withdrawal into silence. -

Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free Static GK E-Book

oliveboard FREE eBooks FAMOUS INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSICIANS & VOCALISTS For All Banking and Government Exams Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free static GK e-book Current Affairs and General Awareness section is one of the most important and high scoring sections of any competitive exam like SBI PO, SSC-CGL, IBPS Clerk, IBPS SO, etc. Therefore, we regularly provide you with Free Static GK and Current Affairs related E-books for your preparation. In this section, questions related to Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists have been asked. Hence it becomes very important for all the candidates to be aware about all the Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. In all the Bank and Government exams, every mark counts and even 1 mark can be the difference between success and failure. Therefore, to help you get these important marks we have created a Free E-book on Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. The list of all the Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists is given in the following pages of this Free E-book on Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. Sample Questions - Q. Ustad Allah Rakha played which of the following Musical Instrument? (a) Sitar (b) Sarod (c) Surbahar (d) Tabla Answer: Option D – Tabla Q. L. Subramaniam is famous for playing _________. (a) Saxophone (b) Violin (c) Mridangam (d) Flute Answer: Option B – Violin Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free static GK e-book Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. Name Instrument Music Style Hindustani -

A Salute to the Music Maestro Cherished Are Those Whose Creativity Adds Melody to the World

A Salute to the Music Maestro Cherished are those whose creativity adds melody to the world It were madness to paint the lily, count the stars, sweeten honey or to fathom Balmurali’s colossal genius These words have been dedicated to the musical genius, Palghat Mani Iyer, but today they apprise the multifaceted Carnatic vocalist, composer, and music guru, Mangalampalli Balamurali Krishna who passed away in Chennai at the age of 86, leaving an irreplaceable void in the realm of Indian Classical Music. The rich imprint of his magnificently rich voice, verses and innovated ragas & taalas live on. M Balamurali Krishna An insignia of illimitable creativity, Balamurali (6 July 1930 – 22 November 2016) Krishna kept the Indian classical tradition alive while modernizing the whole Carnatic music system to make it relatable to the common man. He was a disciple of Parupalli Ramakrishnayya Pantulu, a “I breathe music, think music, talk direct inheritor of the shishya parampara of Tyagaraja, music and music is my energy and I and performed the first full-fledged concert at a am an instrument of music” Thyagaraja Aradhana in Vijayawada at the age of eight. He also gave his first radio concert at the "I like to sing my own creations. tender age of nine and the astounding performance There is a different level of innovation placed him on the list of A-grade artists at the All that one can do with one's own India Radio (AIR), Chennai. A born experimentalist, he bequeathed a new horizon to the two rivulets of compositions. That's exciting. -

Parliamentary Documentation Vol. XXXVIII (16-31 January 2012) No.2

Parliamentary Documentation Vol. XXXVIII (16-31 January 2012) No.2 AGRICULTURE -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES 1 KAKATI, Pradip Distress sale of policy of paddy and vegetables. ASSAM TRIBUNE (GUWAHATI), 2012(18.1.2012) Criticises Government of Assam for neglecting the problems of farmers in the context of selling of paddy by farmers at a far below rate than the Minimum Support Price. ** Agriculture-Agricultural Commodities. -AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH 2 GATES, Bill Make the right choice. HINDUSTAN TIMES (NEW DELHI), 2012(31.1.2012) Emphasises the need for rich countries to continue to invest the modest amounts in agricultural research for providing healthier food to their countrymen. ** Agriculture-Agricultural Research; Food Security. -AGRICULTURAL TRADE-(INDIA-PAKISTAN) 3 BHATTACHARYA, Mondira Spatio-tem poral analys is of Indian basm ati rice trade and its comparison with Pakistan. FOREIGN TRADE REVIEW (NEW DELHI), V.46(No.2), 2011 (Jul/Sep, 2011): P.86-107 ** Agriculture-Agricultural Trade-(India-Pakistan). -CROPS 4 DUTTA SAIKIA, Deepika Multi-cropping with tea. ASSAM TRIBUNE (GUWAHATI), 2012(22.1.2012) Highlights the benefits of multi-cropping with tea in Assam. ** Agriculture-Crops. -CROPS-SEEDS 5 HARBIR SINGH and RAMESH CHAND Seeds Bill, 2011: Some reflections. ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL WEEKLY (MUMBAI), V.46(No.51), 2011 (17.12.2011): P.22-25 ** Agriculture-Crops-Seeds. ** - Keywords 1 -CRUELTY TO ANIMALS 6 DUTT, Anuradha Slaughtering cows is barbaric and offensive to India. PIONEER (NEW DELHI), 2012(17.1.2012) ** Agriculture-Cruelty to Animals. 7 SEN, Manjula Beefed up law. TELEGRAPH (KOLKATA), 2012(18.1.2012) Raises questions on enactm ent of Gau Vansh Pratishedh (Sanshodhan) Vidheyak by the Governm ent of Madh ya Pradesh ** Agriculture-Cruelty to Animals. -

A Case Study on Dhallywood Film Industry, Bangladesh

Research Article, ISSN 2304-2613 (Print); ISSN 2305-8730 (Online) Determinants of Watching a Film: A Case Study on Dhallywood Film Industry, Bangladesh Mst. Farjana Easmin1, Afjal Hossain2*, Anup Kumar Mandal3 1Lecturer, Department of History, Shahid Ziaur Rahman Degree College, Shaheberhat, Barisal, BANGLADESH 2Associate Professor, Department of Marketing, Patuakhali Science and Technology University, Dumki, Patuakhali-8602, BANGLADESH 3Assistant Professor, Department of Economics and Sociology, Patuakhali Science and Technology University, Dumki, Patuakhali-8602, BANGLADESH *E-mail for correspondence: [email protected] https://doi.org/10.18034/abr.v8i3.164 ABSTRACT The purpose of the study is to classify the different factors influencing the success of a Bengali film, and in this regard, a total sample of 296 respondents has been interviewed through a structured questionnaire. To test the study, Pearson’s product moment correlation, ANOVA and KMO statistic has been used and factor analysis is used to group the factors needed to develop for producing a successful film. The study reveals that the first factor (named convenient factor) is the most important factor for producing a film as well as to grab the attention of the audiences by 92% and competitive advantage by 71%, uniqueness by 81%, supports by 64%, features by 53%, quality of the film by 77% are next consideration consecutively according to the general people perception. The implication of the study is that the film makers and promoters should consider the factors properly for watching more films of the Dhallywood industry in relation to the foreign films especially Hindi, Tamil and English. The government can also take the initiative for the betterment of the industry through proper governance and subsidize if possible. -

Part 05.Indd

PART MISCELLANEOUS 5 TOPICS Awards and Honours Y NATIONAL AWARDS NATIONAL COMMUNAL Mohd. Hanif Khan Shastri and the HARMONY AWARDS 2009 Center for Human Rights and Social (announced in January 2010) Welfare, Rajasthan MOORTI DEVI AWARD Union law Minister Verrappa Moily KOYA NATIONAL JOURNALISM A G Noorani and NDTV Group AWARD 2009 Editor Barkha Dutt. LAL BAHADUR SHASTRI Sunil Mittal AWARD 2009 KALINGA PRIZE (UNESCO’S) Renowned scientist Yash Pal jointly with Prof Trinh Xuan Thuan of Vietnam RAJIV GANDHI NATIONAL GAIL (India) for the large scale QUALITY AWARD manufacturing industries category OLOF PLAME PRIZE 2009 Carsten Jensen NAYUDAMMA AWARD 2009 V. K. Saraswat MALCOLM ADISESHIAH Dr C.P. Chandrasekhar of Centre AWARD 2009 for Economic Studies and Planning, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. INDU SHARMA KATHA SAMMAN Mr Mohan Rana and Mr Bhagwan AWARD 2009 Dass Morwal PHALKE RATAN AWARD 2009 Actor Manoj Kumar SHANTI SWARUP BHATNAGAR Charusita Chakravarti – IIT Delhi, AWARDS 2008-2009 Santosh G. Honavar – L.V. Prasad Eye Institute; S.K. Satheesh –Indian Institute of Science; Amitabh Joshi and Bhaskar Shah – Biological Science; Giridhar Madras and Jayant Ramaswamy Harsita – Eengineering Science; R. Gopakumar and A. Dhar- Physical Science; Narayanswamy Jayraman – Chemical Science, and Verapally Suresh – Mathematical Science. NATIONAL MINORITY RIGHTS MM Tirmizi, advocate – Gujarat AWARD 2009 High Court 55th Filmfare Awards Best Actor (Male) Amitabh Bachchan–Paa; (Female) Vidya Balan–Paa Best Film 3 Idiots; Best Director Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots; Best Story Abhijat Joshi, Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Male) Boman Irani–3 Idiots; (Female) Kalki Koechlin–Dev D Best Screenplay Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Abhijat Joshi–3 Idiots; Best Choreography Bosco-Caesar–Chor Bazaari Love Aaj Kal Best Dialogue Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra–3 idiots Best Cinematography Rajeev Rai–Dev D Life- time Achievement Award Shashi Kapoor–Khayyam R D Burman Music Award Amit Tivedi. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Performative Geographies: Trans-Local Mobilities and Spatial Politics of Dance Across & Beyond the Early Modern Coromandel Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/90b9h1rs Author Sriram, Pallavi Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Performative Geographies: Trans-Local Mobilities and Spatial Politics of Dance Across & Beyond the Early Modern Coromandel A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Pallavi Sriram 2017 Copyright by Pallavi Sriram 2017 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Performative Geographies: Trans-Local Mobilities and Spatial Politics of Dance Across & Beyond the Early Modern Coromandel by Pallavi Sriram Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Janet M. O’Shea, Chair This dissertation presents a critical examination of dance and multiple movements across the Coromandel in a pivotal period: the long eighteenth century. On the eve of British colonialism, this period was one of profound political and economic shifts; new princely states and ruling elite defined themselves in the wake of Mughal expansion and decline, weakening Nayak states in the south, the emergence of several European trading companies as political stakeholders and a series of fiscal crises. In the midst of this rapidly changing landscape, new performance paradigms emerged defined by hybrid repertoires, focus on structure and contingent relationships to space and place – giving rise to what we understand today as classical south Indian dance. Far from stable or isolated tradition fixed in space and place, I argue that dance as choreographic ii practice, theorization and representation were central to the negotiation of changing geopolitics, urban milieus and individual mobility. -

Reconsidering Solidarity with Leela Gandhi and Judith Butler

Europe’s Crisis: Reconsidering Solidarity with Leela Gandhi and Judith Butler Giovanna Covi for William V. Spanos, who has shown the way The idea called Europe is important. It deserves loving and nourishing care to grow well and to return its promise. It is a visionary idea shared by winners and losers of World War II, by survivors of the Nazi-Fascist regimes and the Shoah, by large and small countries. It is still little more than just an idea: so far, it has only yielded the suspension of inner wars among the states that became members of the European Union. It is only a germ. Yet, its achievement is outstanding: in the face of the incessant proliferation of wars around the globe, it has secured lasting peace to an increasing number of nations since the 1950s. The idea called Europe is also vague. It has pursued its aim of ending the frequent and bloody wars between neighbours mainly through economic ties, as the Treaty of Maastricht’s failure to promote shared policies underscores. For over half a century, its common policies have been manifestly insufficient and inadequate. It is indeed still only a germ. And its limitations are tremendous: in the face of the rising threats to its own idea of peaceful cohabitation, of the internal rise of violent and hateful forces of sovereignty, of policies of domination, discrimination and exclusion, it is incapable of keeping Europe’s own promise. Such limitations are tangible in the debate about Grexit and the decision regarding Brexit, as well as in the political turn towards totalitarianisms in multiple states. -

National Gallery of Modern Art New Delhi Government of India Vol 1 Issue 1 Jan 2012 Enews NGMA’S Newsletter Editorial Team From

Newsletter JAN 2012 National Gallery of Modern Art New Delhi Government of India Vol 1 Issue 1 Jan 2012 enews NGMA’s Newsletter Editorial Team FroM Ella Datta the DIrector’s Tagore National Fellow for Cultural Research Desk Pranamita Borgohain Deputy Curator (Exhibition) Vintee Sain Update on the year’s activities Assistant Curator (Documentation) The NGMA, New Delhi has been awhirl with activities since the beginning of the year 2011. Kanika Kuthiala We decided to launch a quarterly newsletter to track the events for the friends of NGMA, Assistant Curator New Delhi, our well-wishers and patrons. The first issue however, will give an update of all the major events that took place over the year 2011. The year began with a bang with the th Monika Khanna Gulati, Sky Blue Design huge success of renowned sculptor Anish Kapoor’s exhibition. The 150 Birth Anniversary of Design Rabindranath Tagore, an outstanding creative genius, has acted as a trigger in accelerating our pace. NGMA is coordinating a major exhibition of close to hundred paintings and drawings Our very special thanks to Prof. Rajeev from the collection of NGMA as well as works from Kala Bhavana and Rabindra Bhavana of Lochan, Director NGMA without whose Visva Bharati in Santiniketan, West Bengal. The Exhibition ‘The Last Harvest: Rabindranath generous support this Newsletter would not Tagore’ is the first time that such a major exhibition of Rabindranath’s works is travelling to have been possible. Our Grateful thanks to all so many art centers in Europe and the USA as well as Seoul, Korea. -

Unni Menon…. Is Basically a Malayalam Film Playback Singer

“FIRST ICSI-SIRC CSBF MUSICAL NITE” 11.11.2012 Sunday 6.05 p.m Kamarajar Arangam A/C Chennai In Association With Celebrity Singers . UNNI MENON . SRINIVAS . ANOORADA SRIRAM . MALATHY LAKSHMAN . MICHAEL AUGUSTINE Orchestra by THE VISION AND MISSION OF ICSI Vision : "To be a global leader in promoting Good Corporate Governance” Mission : "To develop high calibre professionals facilitating good Corporate Governance" The Institute The Institute of Company Secretaries of India(ICSI) is constituted under an Act of Parliament i.e. the Company Secretaries Act, 1980 (Act No. 56 of 1980). ICSI is the only recognized professional body in India to develop and regulate the profession of Company Secretaries in India. The Institute of Company Secretaries of India(ICSI) has on its rolls 25,132 members including 4,434 members holding certificate of the practice. The number of current students is over 2,30,000. The Institute of company Secretaries of India (ICSI) has its headquarters at New Delhi and four regional offices at New Delhi, Chennai, Kolkata and Mumbai and 68 Chapters in India. The ICSI has emerged as a premier professional body developing professionals specializing in Corporate Governance. Members of the Institute are rendering valuable services to the Government, Regulatory `bodies, Trade, Commerce, Industry and society at large. Objective of the Fund Financial Assistance in the event of Death of a member of CBSF Upto the age of 60 years • Upto Rs.3,00,000 in deserving cases on receipt of request subject to the Guidelines approved by the Managing -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar.