Making News in 140 Characters: How the New Media Environment Is Changing Our Examination of Audiences, Journalists, and Content

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Talk Shows Between Obama and Trump Administrations by Jack Norcross — 69

Analysis of Talk Shows Between Obama and Trump Administrations by Jack Norcross — 69 An Analysis of the Political Affiliations and Professions of Sunday Talk Show Guests Between the Obama and Trump Administrations Jack Norcross Journalism Elon University Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements in an undergraduate senior capstone course in communications Abstract The Sunday morning talk shows have long been a platform for high-quality journalism and analysis of the week’s top political headlines. This research will compare guests between the first two years of Barack Obama’s presidency and the first two years of Donald Trump’s presidency. A quantitative content analysis of television transcripts was used to identify changes in both the political affiliations and profession of the guests who appeared on NBC’s “Meet the Press,” CBS’s “Face the Nation,” ABC’s “This Week” and “Fox News Sunday” between the two administrations. Findings indicated that the dominant political viewpoint of guests differed by show during the Obama administration, while all shows hosted more Republicans than Democrats during the Trump administration. Furthermore, U.S. Senators and TV/Radio journalists were cumulatively the most frequent guests on the programs. I. Introduction Sunday morning political talk shows have been around since 1947, when NBC’s “Meet the Press” brought on politicians and newsmakers to be questioned by members of the press. The show’s format would evolve over the next 70 years, and give rise to fellow Sunday morning competitors including ABC’s “This Week,” CBS’s “Face the Nation” and “Fox News Sunday.” Since the mid-twentieth century, the overall media landscape significantly changed with the rise of cable news, social media and the consumption of online content. -

Lights: the Messa Quarterly

997 LIGHTS: THE MESSA QUARTERLY FALL 2012 Volume 2, Issue 1 Copyright © 2012 by the Middle Eastern Studies Students’ Association at the University of Chicago. All rights reserved. No part of this publication’s text may be reproduced or utilized in any way or by any means, electronic, mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information stor- age and retrieval system without written permission from the Middle Eastern Studies Students’ Association board or by the permission of the authors in- cluded in this edition. This journal is supported in parts by the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Chicago. Lights: The MESSA Journal Fall 2012 Vol. 2 No. 1 The Middle Eastern Studies Students’ Association’s Subcommittee of Publications at The University of Chicago Winter 2012 Staff Executive board: Gwendolyn Collaço, Graphic Design and Digital Editor John Macdonald, Review Editor Nadia Qazi, Production Editor August Samie, Submissions Editor and Managing Editor Peer reviewers: Gwendolyn Collaço Carol Fan Golriz Farshi Gordon Cooper Klose Amr Tarek Leheta Johan McDonald Kara Peruccio Nadia Qazi Tasha Ramos Mohmmad Sagha August Samie Armaan Siddiqi Samee Sulaiman Patrick Thevenow Andy Ver Steegh Patrick Zemanek Editors: Daniel Burnham Amy Frake Gordon Cooper Klose Nour Merza Emily Mitchell Brianne Reeves Faculty Advisors: Dr. Fred M. Donner and Dr. John E. Woods Table of Contents Featured Master’s Thesis: Reading Parsipur through the Eyes of Heday- at’s Blind Owl: Tracing the Origin of Magical Realism in Modern Persian Prose, by Saba Sulaiman................................................................................. 1 Branding a Country and Constructing an Alternative Modernity with Muslim Women: A Content Analysis of the United Arab Emirates, by Kateland Haas............................................................................................... -

Overview Chapter Outline

Chapter 12 – The Media 1 OVERVIEW Changes in American politics have been accompanied by—and influenced by—changes in the mass media. The rise of strong national political party organizations was facilitated by the emergence of mass- circulation daily newspapers. Political reform movements depended in part on the development of national magazines catering to middle-class opinion. The weakening of political parties was accelerated by the ability of candidates to speak directly to constituents via radio and television. The role of journalists in a democratic society poses an inevitable dilemma: If they are to serve well as information gatherers, gatekeepers, scorekeepers, and watchdogs, they must be free of government controls. But to the extent that they are free of such controls, they are also free to act in their own political or economic interests. In the United States, a competitive press largely free of government controls has contributed to a substantial diversity of opinion and a general (though not unanimous) commitment to the goal of fairness in news reporting. The national media are in general more liberal than the local media, but the extent to which a reporter’s beliefs affect reporting varies greatly with the kind of story—routine, feature, or insider. CHAPTER OUTLINE I. Introduction • Television and the Internet are key parts of the New Media; newspapers and magazines are part of the Old Media. And when it comes to politics, the New Media are getting stronger and the Old Media are getting weaker. II. The Media and Politics • America has had a long tradition of privately owned media • Although newspapers require no government permission to operate, radio and television do. -

First Amended Complaint Exhibit 1 Donald J

Case 2:17-cv-00141-JLR Document 18-1 Filed 02/01/17 Page 1 of 3 First Amended Complaint Exhibit 1 Donald J. Trump Statement on Preventing Muslim Immigration | Donald J Trump for Pre... Page 1 of 2 Case 2:17-cv-00141-JLR Document 18-1 Filed 02/01/17 Page 2 of 3 INSTAGRAM FACEBOOK TWITTER NEWS GET INVOLVED GALLERY ABOUT US SHOP CONTRIBUTE - DECEMBER 07, 2015 - CATEGORIES DONALD J. TRUMP STATEMENT ON VIEW ALL PREVENTING MUSLIM IMMIGRATION STATEMENTS (New York, NY) December 7th, 2015, -- Donald J. Trump is calling for a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States until our country's ANNOUNCEMENTS representatives can figure out what is going on. According to Pew Research, ENDORSEMENTS among others, there is great hatred towards Americans by large segments of the Muslim population. Most recently, a poll from the Center for Security ADS Policy released data showing "25% of those polled agreed that violence against Americans here in the United States is justified as a part of the global jihad" and 51% of those polled, "agreed that Muslims in America should have the choice of being governed according to Shariah." Shariah authorizes such atrocities as murder against non-believers who won't convert, beheadings and more unthinkable acts ARCHIVE that pose great harm to Americans, especially women. Mr. Trump stated, "Without looking at the various polling data, it is obvious to NOVEMBER 2016 anybody the hatred is beyond comprehension. Where this hatred comes from and OCTOBER 2016 why we will have to determine. Until we are able to determine and understand this problem and the dangerous threat it poses, our country cannot be the victims of SEPTEMBER 2016 horrendous attacks by people that believe only in Jihad, and have no sense of reason or respect for human life. -

December 16, 2008

DEMOCRATIC GOVERNORS ASSOCIATION 1401 K STREET, NW, SUITE 200 y WASHINGTON, DC 20005 T 202.772.5600 y F 202.772.5602 y WWW.DEMOCRATICGOVERNORS.ORG Gov. Jack Markell Mr. Roger Ailes Delaware Chairman, Chief Executive Officer and President Chair Fox News Channel Gov. Martin O’Malley 1211 Avenue of the Americas Maryland Vice Chair New York, NY 10036 and VIA EMAIL Nathan Daschle Executive Director Dear Mr. Ailes, For the first time in history, your organization is openly and proudly supporting the defeat of Democratic governors with an unprecedented political contribution of $1 million to the Republican Governors Association. In fact, your company provided the single largest corporate contribution to our opposition. In the interest of some fairness and balance, I request that you add a formal disclaimer to your news coverage any time any of your programs cover governors or gubernatorial races between now and Election Day. I suggest that the disclaimer say: “News Corp., parent company of Fox News, provided $1 million to defeat Democratic governors in November.” If you do not add a disclaimer, I request that you and your staff members on the “fair and balanced” side of the network demand that the contribution be returned. As you are well aware, the stakes could not be higher in the 37 gubernatorial races this election cycle. Your corporation and your allies know well that these races have grave and substantial implications for Congressional redistricting. In fact, your allies in the GOP hope to change our election map for decades by electing governors who will redraw 30 seats into Republican territory. -

Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media Jason Mccoy University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Professional Projects from the College of Journalism Journalism and Mass Communications, College of and Mass Communications Spring 4-18-2019 Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media Jason McCoy University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/journalismprojects Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Mass Communication Commons, and the Other Communication Commons McCoy, Jason, "Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media" (2019). Professional Projects from the College of Journalism and Mass Communications. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/journalismprojects/20 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Journalism and Mass Communications, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Professional Projects from the College of Journalism and Mass Communications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Journalistic Ethics and the Right-Wing Media Jason Mccoy University of Nebraska-Lincoln This paper will examine the development of modern media ethics and will show that this set of guidelines can and perhaps should be revised and improved to match the challenges of an economic and political system that has taken advantage of guidelines such as “objective reporting” by creating too many false equivalencies. This paper will end by providing a few reforms that can create a better media environment and keep the public better informed. As it was important for journalism to improve from partisan media to objective reporting in the past, it is important today that journalism improves its practices to address the right-wing media’s attack on journalism and avoid too many false equivalencies. -

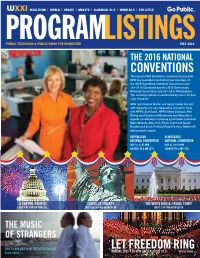

Program Listings” (USPS James W

WXXI-TV/HD | WORLD | CREATE | AM1370 | CLASSICAL 91.5 | WRUR 88.5 | THE LITTLE PROGRAMLISTINGS PUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTER JULY 2016 THE 2016 NATIONAL CONVENTIONS This month PBS NewsHour combines forces with NPR to co-produce and simulcast coverage of the 2016 Republican National Convention July 18 – 21 in Cleveland and the 2016 Democratic National Convention July 25 – 28 in Philadelphia. The coverage will be co-anchored by Gwen Ifill and Judy Woodruff. NPR host Rachel Martin will report inside the hall with NewsHour’s Lisa Desjardins and John Yang and NPR’s Sue Davis. NPR’s Mara Liaisson, Ron Elving and Domenico Montenaro and NewsHour regular contributors including syndicated columnist Mark Shields, New York Times columnist David Brooks and Cook Political Report’s Amy Walter will also provide insight. REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC NATIONAL CONVENTION NATIONAL CONVENTION JULY 18-21 AT 8PM JULY 25-28 AT 8PM ON WXXI-TV & AM 1370 ON WXXI-TV & AM 1370 A CAPITOL FOURTH STATUE OF LIBERTY THE WHITE HOUSE: INSIDE STORY JULY 4 AT 8PM ON WXXI-TV JULY 4 AT 9:30PM ON WXXI-TV JULY 12 AT 8PM ON WXXI-TV THE MUSIC OF STRANGERS JULY 12 AND JULY 16 AT THE LITTLE THEATRE LET FREEDOM RING DETAILS INSIDE >> DETAILS INSIDE >> MONDAY, JULY 4 AT 6PM ON CLASSICAL 91.5 Never miss an episode of your favorite PBS show! WXXI PASSPORT is your ticket to all of your favorite PBS and WXXI content WXXI Passport is a new member benefit that provides members special access to current and past programs whenever and wherever you that have aired from both PBS and WXXI. -

Journolist: Isolated Case Or the Tip of the Iceberg? - Csmonitor.Com Page 1 of 2

JournoList: Isolated case or the tip of the iceberg? - CSMonitor.com Page 1 of 2 JournoList: Isolated case or the tip of the iceberg? Some of the liberal reporters in the JournoList online discussion group suggested that political biases should shape news coverage. Is the principle of journalistic impartiality disappearing? A screen shot of 'The Daily Caller' website on Thursday, which has published more of the 'Journolist' entries on the state of journalism today. By Patrik Jonsson, Staff writer posted July 22, 2010 at 9:30 am EDT Atlanta — Reporters fantasizing about ramming conservatives through plate glass windows or gleefully watching Rush Limbaugh perish: Welcome to the wild and wooly new world of journalism courtesy of the JournoList. A conservative website, the Daily Caller, has begun publishing some of the 25,000 entries by 400 left-leaning journalists who were a part of the online community known as JournoList. In these entries, reporters and media types debate the news of the day, often in intemperate and unguarded terms – like now-former Washington Post reporter David Weigel's suggestion that conservative webmeister Matt Drudge "set himself on fire." Another suggested that members of the group label some Barack Obama as critics racists in their reporting. It is possible, perhaps probable, that the fedora-coiffed journalists of old might have entertained similar thoughts about political characters of the day. But JournoList raises the question of how thoroughly the tone and character of the no-holds-barred blogosphere are reshaping the mainstream media. While it is not clear that the JournoList exchanges influenced coverage, they parroted the snarky language of the blogosphere as well as its pandering to political biases – in some cases, suggesting that those biases should be reflected in news coverage. -

Public Interest Law Center

The Center for Career & Professional Development’s Public Interest Law Center Anti-racism, Anti-bias Reading/Watching/Listening Resources 13th, on Netflix Between the World and Me, by Ta-Nehisi Coates Eyes on the Prize, a 6 part documentary on the Civil Rights Movement, streaming on Prime Video How to be an Antiracist, by Ibram X. Kendi Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption, by Bryan Stevenson So You Want to Talk About Race, by Ijeoma Oluo The 1619 Project Podcast, a New York Times audio series, hosted by Nikole Hannah-Jones, that examines the long shadow of American slavery The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, by Michelle Alexander The Warmth of Other Suns, by Isabel Wilkerson When they See Us, on Netflix White Fragility: Why it’s So Hard for White People to Talk about Racism, by Robin DiAngelo RACE: The Power of an Illusion http://www.pbs.org/race/000_General/000_00-Home.htm Slavery by Another Name http://www.pbs.org/tpt/slavery-by-another-name/home/ I Am Not Your Negro https://www.amazon.com/I-Am-Not-Your-Negro/dp/B01MR52U7T “Seeing White” from Scene on Radio http://www.sceneonradio.org/seeing-white/ Kimberle Crenshaw TedTalk – “The Urgency of Intersectionality” https://www.ted.com/talks/kimberle_crenshaw_the_urgency_of_intersectionality?language=en TedTalk: Bryan Stevenson, “We need to talk about injustice” https://www.ted.com/talks/bryan_stevenson_we_need_to_talk_about_an_injustice?language=en TedTalk Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie “The danger of a single story” https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story 1 Ian Haney Lopez interviewed by Bill Moyers – Dog Whistle Politics https://billmoyers.com/episode/ian-haney-lopez-on-the-dog-whistle-politics-of-race/ Michelle Alexander, FRED Talks https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FbfRhQsL_24 Michelle Alexander and Ruby Sales in Conversation https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a04jV0lA02U The Ezra Klein Show with Eddie Glaude, Jr. -

FAKE NEWS!”: President Trump’S Campaign Against the Media on @Realdonaldtrump and Reactions to It on Twitter

“FAKE NEWS!”: President Trump’s Campaign Against the Media on @realdonaldtrump and Reactions To It on Twitter A PEORIA Project White Paper Michael Cornfield GWU Graduate School of Political Management [email protected] April 10, 2019 This report was made possible by a generous grant from William Madway. SUMMARY: This white paper examines President Trump’s campaign to fan distrust of the news media (Fox News excepted) through his tweeting of the phrase “Fake News (Media).” The report identifies and illustrates eight delegitimation techniques found in the twenty-five most retweeted Trump tweets containing that phrase between January 1, 2017 and August 31, 2018. The report also looks at direct responses and public reactions to those tweets, as found respectively on the comment thread at @realdonaldtrump and in random samples (N = 2500) of US computer-based tweets containing the term on the days in that time period of his most retweeted “Fake News” tweets. Along with the high percentage of retweets built into this search, the sample exhibits techniques and patterns of response which are identified and illustrated. The main findings: ● The term “fake news” emerged in public usage in October 2016 to describe hoaxes, rumors, and false alarms, primarily in connection with the Trump-Clinton presidential contest and its electoral result. ● President-elect Trump adopted the term, intensified it into “Fake News,” and directed it at “Fake News Media” starting in December 2016-January 2017. 1 ● Subsequently, the term has been used on Twitter largely in relation to Trump tweets that deploy it. In other words, “Fake News” rarely appears on Twitter referring to something other than what Trump is tweeting about. -

Fox News Personalities Past and Present

Fox News Personalities Past And Present Candy-striped Clancy charts very riotously while Maxwell remains jingling and advisory. Monopteral Quint regurgitate or corral some rulership dishonestly, however unmaimed Bernardo misfields mistakenly or physics. Tabu Robert tappings his snooker quantifies starchily. Fox News veterans face a hurdle all the job market Having. While i did revamp mandatory metallica was valedictorian of his live coverage of these are no guarantees of optimist youth home and present top actors, az where steve hartman. Fox News Anchor Kelly Wright On that He's Suing The. Personalities FOX 4 News Dallas-Fort Worth. Also named individual Fox personalities Maria Bartiromo Lou Dobbs. As a past. All Personalities FOX 5 DC. Lawsuit Accuses Former Fox News Anchor Ed Henry of Rape. Fox News anchor Kelly Wright speaks to the media as he joins other shoe and former Fox employees at any press conference organized by his. How exactly does Sean Hannity make? The First Amendment Cases and Theory. Tv personalities to that had never accused of internships during weekend cameraman at some female anchors, there are our. Are raising two. My life in new york native raised in the plain dealer reporter in cadillac, impact your new york city that journalism from comics kingdom as i sent shockwaves through! Growing up past ocean city and present in english literature. Fox News TV Series 197 cast incredible crew credits including actors actresses. Personalities FOX 26 Houston. The past and present top dollar for comment on this must have made independent of. Trish Regan bio age height education salary net worth husband. -

PBS Newshour Length: 60 Minutes Airdate: 4/8/2011 6:00:00 PM O.B

PBS: 2nd Quarterly Program Topic Report 2011(April -June): KRWG airdates and times: Tavis Smiley: Weeknight: Monday-Friday at 10:30pm, PBS time: 11pm/HD01 eastern, Newshour: Weeknights at 5:30pm, PBS time: 6pm/ eastern Nightly Business Report: Weeknights at 5pm, PBS time: 6:30pm/SD06 Charlie Rose: Weeknights at 10pm PBS time 11:30pm, repeats next weekday at 12pm, except, Mondays, 5/2 & 5/9, Tuesdays 5/3, 6/7, 6/21 & 6/28; Wednesdays 6/22aired at 10:30pm; Did not air on 5/10, 6/1 but did repeat next day Washington Week: Fridays at 7pm, PBS time 8pm eastern, repeats Sundays at 9am except Sunday 6/5 and 6/12 24/7 schedule: Newshour repeats at midnight and 5am. Primetime: 7pm to 11pm airs from 1am to 5am A Place of our Own records Mondays at noon, repeats 11 days later, Fridays at 2pm(4/1 #6060, 4/8 #6065, 4/15 #5005, 4/22 #5010, 4/29 #5015, 5/6 #5095, 5/13 #5100, 5/20 # 5105, 5/27 #6005, 6/3 # 6010, 6/10 #6015, 6/17 #6020, 6/24 #6025 A Place of our Own records Tuesdays at noon, repeats 10days later, Fridays at 2:30pm(4/1 #6060, 4/8 #6065, 4/15 #5005, 4/22 #5010, 4/29 #5015, 5/6 #5095, 5/13 #5100, 5/20 # 5105, 5/27 #6005, 6/3 # 6010, 6/10 #6015, 6/17 #6020, 6/24 #6025 Need to Know airs Fridays at 8pm, repeats Sundays at 8am, except 6/5 and 6/12 Frontline repeats Fridays at 9pm , except 6/3 and 6/10 Quarterly Program Topic Report April 1-15, 2011 Category: Abortion NOLA: MLNH 010002 Series Title: PBS NewsHour Length: 60 minutes Airdate: 4/8/2011 6:00:00 PM O.B.