C/1764 Seaman James W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Kriegsmarine U VII. Osztályú Tengeralattjárói

Haditechnika-történet Kelecsényi István* – Sárhidai Gyula** Akik majdnem megnyerték az Atlanti csatát – A Kriegsmarine U VII. osztályú tengeralattjárói I. rész 1. ábra. VII. osztályú U-boot bevetésre indul a kikötőből (Festmény) AZ előzmények főleg kereskedelmi hajót süllyesztettek el 199 darabos veszteség ellenében. A német búvárnaszádok a háború Az első világháború után a békefeltételek nem engedték során komoly problémát okoztak az antant hatalmaknak a meg Németországnak a tengeralattjárók hadrendben tartá- nyersanyag utánpótlásában és élelmiszerszállítások bizto- sát. Ennek oka, hogy a Nagy Háborúban több mint 5000, sításában. ÖSSZEFOGLALÁS: A németek közepes méretű tengeralattjáró típusa a VII. ABSTRACT: The Class VII U-boats were the German medium-size submarine osztály volt. A német haditengerészet legnagyobb ászai – Günther Prien type. The greatest aces of the German Navy – Corvette captain Günther Prien, korvettkapitány, Otto Kretschmer fregattkapitány és Joachim Schepke fre- Frigate captain Otto Kretschmer and Frigate captain Joachim Schepke – gattkapitány – ezeken a hajókon szolgáltak. A VII. osztály változatai elsősor- served on these boats. Variants of the Class VII fought mainly in the Atlantic ban az Atlanti-óceánon, a brit utánpótlási vonalak fő hadszínterén harcoltak, Ocean, on the main battlefield of the British supply lines, and between 1941 és 1941 és 1943 között majdnem sikerült kiéheztetniük és térdre kényszerí- and 1943 they almost starved and brought to heels the Great Britain. The teniük Nagy-Britanniát. A németek -

9832 Supplement to the London Gazette, 31 July, 1919

9832 SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 31 JULY, 1919. CENTRAL CHANCERY OF THE ORDERS Commander (now Captain) Bernard William. OF KNIGHTHOOD. Murray Fairbairn, R.N. St. James's Palace, S.W., For valuable services as Executive Officer of H.M. Ships "Cochrane" and "War- 31st July, 1919. spite," and in the Naval Ordnance Depart- The KING has been graciously pleased to ment, Admiralty. give orders for the following appointments to Surgeon-Lieutenant George William Marshall the Most Excellent Order of the British Fmdlay, M.B., R.N. Empire in recognition of the services of the For valuable services as Medical Officer of undermentioned Officers during the War: — the Royal Naval Depot, Port Said. To be Commanders of the Military Division of Lieutenant Otto Barnes Patrick Flood, R.N.R. the said Most Excellent Order:— For valuable services as Resident Naval Commander (acting Captain) Ernest Edward Officer, Suez. Alexander Betts, R.N. Commander Geoffrey Herbert Freyberg, R.N. For valuable services as Senior British For valuable services as Navigating Officer Naval Officer, Suez Canal. of H.M.S. "Valiant.'" Commander (acting Captain) Arthur Edward Commander Malcolm Kenneth Grant, R.N. Dunn, R.D., R.N.R. For valuable* services in the Department For valuable services as a Commodore of of the Director of Torpedoes and Mining, Convoys, and on the Staff of the British Admiralty. Senior Naval Officer, New York. Engineer Lieutenant Harry Hunter, R.N. Engineer Captain Arthur Robert Grant, R.N. For valuable services in H.M.S. "Bar- For valuable services as Squadron ham." Engineer of the Fifth and Second Battle Lieutenant-Commander Robert Beaufin Irving, Squadrons. -

The British Commonwealth and Allied Naval Forces' Operation with the Anti

THE BRITISH COMMONWEALTH AND ALLIED NAVAL FORCES’ OPERATION WITH THE ANTI-COMMUNIST GUERRILLAS IN THE KOREAN WAR: WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE OPERATION ON THE WEST COAST By INSEUNG KIM A dissertation submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham May 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines the British Commonwealth and Allied Naval forces operation on the west coast during the final two and a half years of the Korean War, particularly focused on their co- operation with the anti-Communist guerrillas. The purpose of this study is to present a more realistic picture of the United Nations (UN) naval forces operation in the west, which has been largely neglected, by analysing their activities in relation to the large number of irregular forces. This thesis shows that, even though it was often difficult and frustrating, working with the irregular groups was both strategically and operationally essential to the conduct of the war, and this naval-guerrilla relationship was of major importance during the latter part of the naval campaign. -

Japan Im Ersten Weltkrieg

ÖSTERREICHISCHEÖMZ MILITÄRISCHE ZEITSCHRIFT In dieser Onlineausgabe Harald Pöcher Japan im Ersten Weltkrieg Nikolaus Scholik Power-Projection vs Anti-Access/Area-Denial (A2/AD) Die operationellen Konzepte von U.S. Navy (USN) und Peoples Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) im Indo-Pazifischen Raum Andreas Armborst Dschihadismus im Irak Andreas Steiger Die Berufsoffiziersausbildung an der Theresianischen Militärakademie in Wr. Neustadt Beiträge zur Geschichte des Bundesheeres der 1. Republik von 1934-1938 Zusätzlich in der Printausgabe Walter Schilling Die Problematik der pazifistischen Grundströmung in Deutschland Hans Krech Die direkte Einflussnahme der strategischen Führungsebene von Al Qaida auf interne Konflikte in den Regionalorganisationen Heino Matzken Zwist statt Liebe in der Geburtskirche Ewiger christlicher Zankapfel auch Spielball im palästinensisch-israelischen Staatspoker! Klaus-Jürgen Bremm Die elektrische Telegraphie als Mittel militärischer Führung und der Nachrichtengewinnung in den deutschen Einigungskriegen sowie zahlreiche Berichte zur österreichischen und internationalen Verteidigungspolitik ÖMZ 4/2014-Online ÖMZ itärisc Mil he Z e ei h ts sc c i h h r Japan im Ersten Weltkrieg c i i f e t r r e t s Ö w Peer Revie Harald Pöcher 1808 er japanische Beitrag zum Ersten Weltkrieg Nation-starke Armee). Unmittelbar nach der Öffnung des führte zu einer Neugestaltung des westpazi- Landes gaben sich die ausländischen Militärdelegationen - Dfisch-ostasiatischen Raumes und schuf damit auch in der Hoffnung auf gute Geschäfte für ihre Rüstungs- -

The Forgotten Fronts the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Forgotten Fronts Forgotten The

Ed 1 Nov 2016 1 Nov Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The Forgotten Fronts The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Forgotten Fronts Creative Media Design ADR005472 Edition 1 November 2016 THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | i The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The British Army Campaign Guide to the Forgotten Fronts of the First World War 1st Edition November 2016 Acknowledgement The publisher wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in providing text, images, multimedia links and sketch maps for this volume: Defence Geographic Centre, Imperial War Museum, Army Historical Branch, Air Historical Branch, Army Records Society,National Portrait Gallery, Tank Museum, National Army Museum, Royal Green Jackets Museum,Shepard Trust, Royal Australian Navy, Australian Defence, Royal Artillery Historical Trust, National Archive, Canadian War Museum, National Archives of Canada, The Times, RAF Museum, Wikimedia Commons, USAF, US Library of Congress. The Cover Images Front Cover: (1) Wounded soldier of the 10th Battalion, Black Watch being carried out of a communication trench on the ‘Birdcage’ Line near Salonika, February 1916 © IWM; (2) The advance through Palestine and the Battle of Megiddo: A sergeant directs orders whilst standing on one of the wooden saddles of the Camel Transport Corps © IWM (3) Soldiers of the Royal Army Service Corps outside a Field Ambulance Station. © IWM Inside Front Cover: Helles Memorial, Gallipoli © Barbara Taylor Back Cover: ‘Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red’ at the Tower of London © Julia Gavin ii | THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | iii ISBN: 978-1-874346-46-3 First published in November 2016 by Creative Media Designs, Army Headquarters, Andover. -

Seeschlachten Im Atlantik (Zusammenfassung)

Seeschlachten im Atlantik (Zusammenfassung) U-Boot-Krieg (aus Wikipedia) 07_48/U 995 vom Typ VII C/41, der meistgebauten U-Boot-Klasse im Zweiten Weltkrieg Als U-Boot-Krieg (auch "Unterseebootkrieg") werden Kampfhandlungen zur See bezeichnet, bei denen U-Boote eingesetzt werden, um feindliche Kriegs- und Frachtschiffe zu versenken. Die Bezeichnung "uneingeschränkter U-Boot-Krieg" wird verwendet, wenn Schiffe ohne vorherige Warnung angegriffen werden. Der Einsatz von U-Booten wandelte sich im Laufe der Zeit vom taktischen Blockadebrecher zum strategischen Blockademittel im Rahmen eines Handelskrieges. Nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg änderte sich die grundsätzliche Einsatzdoktrin durch die Entwicklung von Raketen tragenden Atom- U-Booten, die als Träger von Kernwaffen eine permanente Bedrohung über den maritimen Bereich hinaus darstellen. Im Gegensatz zum Ersten und Zweiten Weltkrieg fand hier keine völkerrechtliche Weiterentwicklung zum Einsatz von U-Booten statt. Der Begriff wird besonders auf den Ersten und Zweiten Weltkrieg bezogen. Hierbei sind auch völkerrechtliche Rahmenbedingungen von Bedeutung. Anfänge Während des Amerikanischen Bürgerkrieges wurden 1864 mehrere handgetriebene U-Boote gebaut. Am 17. Februar 1864 versenkte die C.S.S. H. L. Hunley durch eine Sprengladung das Kriegsschiff USS Housatonic der Nordstaaten. Es gab 5 Tote auf dem versenkten Schiff. Die Hunley gilt somit als erstes U-Boot der Welt, das ein anderes Schiff zerstört hat. Das U-Boot wurde allerdings bei dem Angriff auf die Housatonic durch die Detonation schwer beschädigt und sank, wobei auch seine achtköpfige Besatzung getötet wurde. Auftrag der Hunley war die Brechung der Blockade des Südstaatenhafens Charleston durch die Nordstaaten. Erster Weltkrieg Die technische Entwicklung der U-Boote bis zum Beginn des Ersten Weltkrieges beschreibt ein Boot, das durch Dampf-, Benzin-, Diesel- oder Petroleummaschinen über Wasser und durch batteriegetriebene Elektromotoren unter Wasser angetrieben wurde. -

At the Double a Snowy Douaumont

JOURNAL February 48 2013 At the Double A snowy Douaumont Please note that Copyright for any articles contained in this Journal rests with the Authors as shown. Please contact them directly if you wish to use their material. 1 Hello All An interesting article in the Times caught my eye a couple of weeks ago. Carrying the heading: ‘Dramatic boost for campaign to honour first black officer’, it covers the life of Walter Tull, a coloured professional footballer with Tottenham Hotspur and Northampton Town, who joined up in the ranks at the beginning of the War, enlisting in the 17th Battalion (1st Footballer’s), Middlesex Regiment as it came to be known, and was later commissioned, before being killed in March, 1918. The campaign referred to, asks the government to award him a posthumous Military Cross for his bravery, and indeed, he had been recommended for the MC for courageous acts undertaken some time before his death. But, one presumes that, given that a unit could only receive so many awards in a month, more meritorious acts were recognised, and so Walter Tull’s gallantry sadly went unrewarded. The award of a posthumous MC to a very brave man does sound like a nice idea, but in these specific circumstances is it not woolly-headed? Politically correct even? I think that it is both, and would set an unwelcome precedent. With the rationing of medals, whoever had to decide who should receive the six, shall we say, awards from ten recommendations had to make a judgement call, and these decisions were made at Brigade and Division level. -

Barham Coverup

Jason Stevenson www.webatomics.com World War II Magazine December 2004 The Barham Conspiracy By Jason Stevenson In late November 1941 the British battleship HMS Barham was attacked and sunk by a U-boat off the coast of Egypt. In March of 1944 Mrs. Helen Duncan, a well-known Scottish spiritualist and medium, went on trial in London’s Old Bailey for conspiracy to violate the 1735 Witchcraft Act. In the intervening years these two seemingly disparate events became woven together in a complicated wartime tale of naval disaster, government coverup, a drowned sailor purportedly speaking from a watery grave, and a modern-day witch trial that Winston Churchill described as “absolute tomfoolery.” An Afternoon Tragedy On the afternoon of November 25, 1941 Barham and two other battleships of the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean Fleet cruised off the Egyptian coast of Cyrenaica to provide distant cover for an attack on Italian convoys. Though constantly zigzagging and screened by eight destroyers, the battleships sailed into peril. Undetected beneath the calm water, Kplt. Hans-Diedrich Von Tiesenhausen maneuvered his U-331 inside the British destroyers and launched four torpedoes at a battleship looming in his periscope. The 31,000 ton Barham stood no chance when three of the torpedoes exploded against her port side. Obscured by enormous spouts of water, the stricken warship lost all electrical power and began listing heavily; a scene recorded by a cameraman aboard the nearby battleship HMS Valiant. Still plowing forward into the sea, Barham rolled onto her beam ends and blew up in a tremendous magazine explosion just four minutes after the first torpedo struck. -

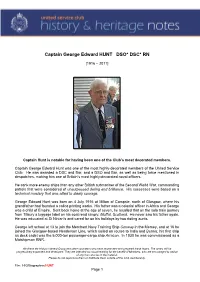

Captain George Edward HUNT DSO* DSC* RN

Captain George Edward HUNT DSO* DSC* RN [1916 – 2011] Captain Hunt is notable for having been one of the Club’s most decorated members. Captain George Edward Hunt was one of the most highly-decorated members of the United Service Club. He was awarded a DSC and Bar, and a DSO and Bar, as well as being twice mentioned in despatches, making him one of Britain’s most highly-decorated naval officers. He sank more enemy ships than any other British submariner of the Second World War, commanding patrols that were considered of unsurpassed daring and brilliance. His successes were based on a technical mastery that was allied to steely courage. George Edward Hunt was born on 4 July 1916 at Milton of Campsie, north of Glasgow, where his grandfather had founded a calico printing works. His father was a colonial officer in Africa and George was a child of Empire. Sent back home at the age of seven, he recalled that on the solo train journey from Tilbury a luggage label on his coat read simply: Moffat, Scotland. He never saw his father again. He was educated at St Ninian’s and cared for on his holidays by two doting aunts. George left school at 13 to join the Merchant Navy Training Ship Conway in the Mersey, and at 16 he joined the Glasgow-based Henderson Line, which sailed on routes to India and Burma; his first ship as deck cadet was the 5,000-ton passenger-cargo ship Arracan. In 1930 he was commissioned as a Midshipman RNR. -

REMNI Lisburnrn,RM

remembrance ni Lisburn’s service at sea in WW2 Tommy Jess 1923 - 2015 Survived ship loss on the Murmansk run Page !1 Survivors photographed in Greenock, Scotland on their return March 1945. Thomas Jess - back row second from right Thomas Jess was in HMS Lapwing and was blown 10 yards across the deck when a torpedo struck the destroyer on a bitterly cold morning in the final few months of the war. He was one of 61 survivors. 58 sailors died on 20/03/1945, on board the HMS Lapwing, which was just a day's sail from the Russian port of Murmansk when it was torpedoed without warning by the German submarine U-968. "The explosion just lifted me off my feet, skinning all my knuckles," said Jess, one of several sailors from Northern Ireland on board the Lapwing. "But I was lucky as I always wore my lifebelt, which was my best friend at sea. Other fellows were more careless. There was one poor man who tried to make his way below for his lifebelt but he never got back up on deck." Page !2 HMS Lapwing After the torpedo ripped through the ship's hull, he stayed at his post until the abandon ship order was given. Then he jumped into the freezing sea and was lucky enough to be pulled onto a raft that had been thrown overboard by the crew. "There were about 16 of us on the raft when we set off and then one by one they fell off in the cold. I fell unconscious while we drifted for at least two hours...There were just six of us pulled onboard HMS Savage when we were rescued . -

Never Has So Much Been Owed…

First published in 2005 1 TEWKESBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY Publication No. 4 [VE75 Website Edition] “Never has so much been owed …..” Commemoration of Local War Dead in World War II Contents Introduction 2 District Role of Honour 3 Contribution of Local War Dead to World War II 5 Statistics 15 Parish Rolls of Honour: Conclusion 72 2 Tewkesbury Historical Society “Never has so much been owed …..” Commemoration of Local War Dead in World War II Introduction This book is an attempt to provide biographical information upon the 63 men and women who sacrificed their lives in this war and who are commemorated in some way in the localities of Tewkesbury,1 Twyning, Forthampton, Apperley and Tredington.2 The main sources of information are ✓ The invaluable website of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission which has so meticulously logged the data of the war dead, but which also tends so lovingly their graves all over the world. In this task, I am grateful for the CWGC permitting us to use their images and to Jade Atkinson. ✓ The Tewkesbury Register (the ancestor of the “Echo”) which is patiently researched by the late David Willavoys. We are also very grateful to John Pocock who has patiently transcribed information researched by David. We have used photographs taken with a digital camera, but the quality is inevitably variable. ✓ Sam Eedle for his superb cover design. ✓ Those families who have responded to press appeals for more information. An exhibition was mounted at the Tewkesbury Library between 9 and 21 July 2005 and we learned more information about individuals as a result of this exercise.3 There are two major innovations in commemorating the war dead of this War: ✓ Service women who lost their lives are included unlike in WWI ✓ One civilian, who lost his life in a Flying Bomb attack, is included There are, however, inconsistencies and we hope that, as a result of this exercise, those names omitted from the Memorials will be included, even though the gesture would be 60 years late. -

Rofworld •WKR II

'^"'^^«^.;^c_x rOFWORLD •WKR II itliiro>iiiiii|r«trMit^i^'it-ri>i«fiinit(i*<j|yM«.<'i|*.*>' mk a ^. N. WESTWOOD nCHTING C1TTDC or WORLD World War II was the last of the great naval wars, the culmination of a century of warship development in which steam, steel and finally aviation had been adapted for naval use. The battles, both big and small, of this war are well known, and the names of some of the ships which fought them are still familiar, names like Bismarck, Warspite and Enterprise. This book presents these celebrated fighting ships, detailing both their war- time careers and their design features. In addition it describes the evolution between the wars of the various ship types : how their designers sought to make compromises to satisfy the require - ments of fighting qualities, sea -going capability, expense, and those of the different naval treaties. Thanks to the research of devoted ship enthusiasts, to the opening of government archives, and the publication of certain memoirs, it is now possible to evaluate World War II warships more perceptively and more accurately than in the first postwar decades. The reader will find, for example, how ships in wartime con- ditions did or did not justify the expecta- tions of their designers, admiralties and taxpayers (though their crews usually had a shrewd idea right from the start of the good and bad qualities of their ships). With its tables and chronology, this book also serves as both a summary of the war at sea and a record of almost all the major vessels involved in it.