Status of Trophy Hunting in Zambia for the Period 2003 – 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pending World Record Waterbuck Wins Top Honor SC Life Member Susan Stout Has in THIS ISSUE Dbeen Awarded the President’S Cup Letter from the President

DSC NEWSLETTER VOLUME 32,Camp ISSUE 5 TalkJUNE 2019 Pending World Record Waterbuck Wins Top Honor SC Life Member Susan Stout has IN THIS ISSUE Dbeen awarded the President’s Cup Letter from the President .....................1 for her pending world record East African DSC Foundation .....................................2 Defassa Waterbuck. Awards Night Results ...........................4 DSC’s April Monthly Meeting brings Industry News ........................................8 members together to celebrate the annual Chapter News .........................................9 Trophy and Photo Award presentation. Capstick Award ....................................10 This year, there were over 150 entries for Dove Hunt ..............................................12 the Trophy Awards, spanning 22 countries Obituary ..................................................14 and almost 100 different species. Membership Drive ...............................14 As photos of all the entries played Kid Fish ....................................................16 during cocktail hour, the room was Wine Pairing Dinner ............................16 abuzz with stories of all the incredible Traveler’s Advisory ..............................17 adventures experienced – ibex in Spain, Hotel Block for Heritage ....................19 scenic helicopter rides over the Northwest Big Bore Shoot .....................................20 Territories, puku in Zambia. CIC International Conference ..........22 In determining the winners, the judges DSC Publications Update -

Population, Distribution and Conservation Status of Sitatunga (Tragelaphus Spekei) (Sclater) in Selected Wetlands in Uganda

POPULATION, DISTRIBUTION AND CONSERVATION STATUS OF SITATUNGA (TRAGELAPHUS SPEKEI) (SCLATER) IN SELECTED WETLANDS IN UGANDA Biological -Life history Biological -Ecologicl… Protection -Regulation of… 5 Biological -Dispersal Protection -Effectiveness… 4 Biological -Human tolerance Protection -proportion… 3 Status -National Distribtuion Incentive - habitat… 2 Status -National Abundance Incentive - species… 1 Status -National… Incentive - Effect of harvest 0 Status -National… Monitoring - confidence in… Status -National Major… Monitoring - methods used… Harvest Management -… Control -Confidence in… Harvest Management -… Control - Open access… Harvest Management -… Control of Harvest-in… Harvest Management -Aim… Control of Harvest-in… Harvest Management -… Control of Harvest-in… Tragelaphus spekii (sitatunga) NonSubmitted Detrimental to Findings (NDF) Research and Monitoring Unit Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA) Plot 7 Kira Road Kamwokya, P.O. Box 3530 Kampala Uganda Email/Web - [email protected]/ www.ugandawildlife.org Prepared By Dr. Edward Andama (PhD) Lead consultant Busitema University, P. O. Box 236, Tororo Uganda Telephone: 0772464279 or 0704281806 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] Final Report i January 2019 Contents ACRONYMS, ABBREVIATIONS, AND GLOSSARY .......................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... viii 1.1Background ........................................................................................................................... -

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) Categories Approved by Recommendation 4.7, As Amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7, as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties. Note for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Bureau. Compilers are strongly urged to provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of maps. 1. Name and address of the compiler of this form: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. DD MM YY Zambia Wildlife Authority Private Bag 1 Designation date Site Reference Number Chilanga, Zambia Email: [email protected] Tel: 260-01-278365 or 278335 Fax: 260-01-278299 or 278365 2. Date this sheet was completed/updated: 02 September 2005 3. Country: Zambia 4. Name of the Ramsar site: LUKANGA SWAMPS 5. Map of site included: Refer to Annex III of the Explanatory Note and Guidelines, for detailed guidance on provision of suitable maps. a) hard copy (required for inclusion of site in the Ramsar List): yes -or- no b) digital (electronic) format (optional): yes -or- no 6. Geographical coordinates (latitude/longitude): 14o 08' - 14o 40'S, 27o 10' - 28o 05'E 7. General location: Include in which part of the country and which large administrative region(s), and the location of the nearest large town. Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS), page 2 The Swamps are found in the Central Province, west of Kabwe town on the east bank of the Kafue River along the stretch between Machiya Ferry and Mswebi. -

Bangweulu Hunting Memo Who: This Brief Document Is for the Public

Bangweulu Hunting Memo Who: This brief document is for the public (to be placed on our website), key donors and partners who have a stake or vested interested in sustainable use of wildlife resources. Background Bangweulu Wetlands is a vast wetland ecosystem that is situated in north-eastern Zambia, covering an area of 6,000 km2. Bangweulu is unique in that it is a Game Management Area (GMA) and a community- owned protected wetland, home to 50,000 people who retain the right to sustainably harvest its natural resources and who depend on the natural resources the park provides. These wetlands and the adjoining lake Bangweulu are biologically significant. The area has been declared a RAMSAR site and contains diverse flora and fauna, including more than 433 bird species. The GMA encompasses most of the distribution of the endemic black lechwe antelope, as well as several other iconic species unique to the area, including the shoebill stork, and remnant elephant and buffalo populations. This landscape has been managed by the Bangweulu Wetlands Management Board (BWMB) since 2008. The Board is a partnership between conservation organisation African Parks, the Zambia Department of National Parks and Wildlife (DNPW), as well as six Community Resource Boards associated with each Chiefdom. The mission of BWMB is to restore the functioning of the Bangweulu ecosystem, a critical wetland habitat of rich biodiversity that provides socio-economic benefits to the local communities. Prior to the partnership with African Parks, rampant poaching and unrestricted fishing had depleted the area’s natural resources, including the black lechwe population. -

An Invasive Species Assessment in Zambia

Public Document Clearing Kariba weed (Salvinia molesta) from Lukanga Swamp, central Zambia (Image courtesy of BirdLife International) Action on Invasives An invasive species system assessment in Zambia Kate Constantine, Joyce Mulila-Mitti and Frances Williams December 2020 KNOWLEDGE FOR LIFE An invasive species assessment in Zambia Acknowledgements The authors would like to acknowledge the critical contributions of Noah Phiri, Judith Chowa and Ivan Rwomushana towards facilitating this work. CABI is an international intergovernmental organisation, and we gratefully acknowledge the core financial support from our member countries (and lead agencies) including the United Kingdom (Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office), China (Chinese Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs), Australia (Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research), Canada (Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada), Netherlands (Directorate-General for International Cooperation), and Switzerland (Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation). The Action on Invasives Programme is supported by the United Kingdom Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office and The Netherlands Directorate-General for International Cooperation. This report is the Copyright of CAB International, on behalf of the sponsors of this work where appropriate. It presents unpublished research findings, which should not be used or quoted without written agreement from CAB International. Unless specifically agreed otherwise in writing, all information herein should be treated as confidential. 1 Executive summary Invasive species are a serious and growing problem in Zambia. The objective of this study was to understand the current status of the invasive species system in Zambia and describe, evaluate and assess the responsiveness of the system to address the threat of invasive species to the country. A methodology was developed that identifies areas to address to strengthen the system, as well as a baseline against which changes in responsiveness of the system can be assessed at a later date if required. -

Mammal Movements & Migrations

AWF FOUR CORNERS TBNRM PROJECT : REVIEWS OF EXISTING BIODIVERSITY INFORMATION i Published for The African Wildlife Foundation's FOUR CORNERS TBNRM PROJECT by THE ZAMBEZI SOCIETY and THE BIODIVERSITY FOUNDATION FOR AFRICA 2004 PARTNERS IN BIODIVERSITY The Zambezi Society The Biodiversity Foundation for Africa P O Box HG774 P O Box FM730 Highlands Famona Harare Bulawayo Zimbabwe Zimbabwe Tel: +263 4 747002-5 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.biodiversityfoundation.org Website : www.zamsoc.org The Zambezi Society and The Biodiversity Foundation for Africa are working as partners within the African Wildlife Foundation's Four Corners TBNRM project. The Biodiversity Foundation for Africa is responsible for acquiring technical information on the biodiversity of the project area. The Zambezi Society will be interpreting this information into user-friendly formats for stakeholders in the Four Corners area, and then disseminating it to these stakeholders. THE BIODIVERSITY FOUNDATION FOR AFRICA (BFA is a non-profit making Trust, formed in Bulawayo in 1992 by a group of concerned scientists and environmentalists. Individual BFA members have expertise in biological groups including plants, vegetation, mammals, birds, reptiles, fish, insects, aquatic invertebrates and ecosystems. The major objective of the BFA is to undertake biological research into the biodiversity of sub-Saharan Africa, and to make the resulting information more accessible. Towards this end it provides technical, ecological and biosystematic expertise. THE ZAMBEZI SOCIETY was established in 1982. Its goals include the conservation of biological diversity and wilderness in the Zambezi Basin through the application of sustainable, scientifically sound natural resource management strategies. -

COX BRENTON, a C I Date: COX BRENTON, a C I USDA, APHIS, Animal Care 16-MAY-2018 Title: ANIMAL CARE INSPECTOR 6021 Received By

BCOX United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Insp_id Inspection Report Customer ID: ALVIN, TX Certificate: Site: 001 Type: FOCUSED INSPECTION Date: 15-MAY-2018 2.40(b)(2) DIRECT REPEAT ATTENDING VETERINARIAN AND ADEQUATE VETERINARY CARE (DEALERS AND EXHIBITORS). ***In the petting zoo, two goats continue to have excessive hoof growth One, a large white Boer goat was observed walking abnormally as if discomforted. ***Although the attending veterinarian was made aware of the Male Pere David's Deer that had a front left hoof that appeared to be twisted approximately 90 degrees outward from the other three hooves and had a long hoof on the last report, the animal has not been assessed and a treatment pan has not been created. This male maneuvers with a limp on the affect leg. ***A female goat in the nursery area had a large severely bilaterally deformed udder. The licensee stated she had mastitis last year when she kidded and he treated her. The animal also had excessive hoof length on its rear hooves causing them to curve upward and crack. The veterinarian has still not examined this animal. Mastitis is a painful and uncomfortable condition and this animal has a malformed udder likely secondary to an inappropriately treated mastitis. ***An additional newborn fallow deer laying beside an adult fallow deer inside the rhino enclosure had a large round spot (approximately 1 1/2 to 2 inches round) on its head that was hairless and grey. ***A large male Watusi was observed tilting its head at an irregular angle. -

Accounting for Intraspecific Variation Transforms Our Understanding of Artiodactyl Social Evolution

ACCOUNTING FOR INTRASPECIFIC VARIATION TRANSFORMS OUR UNDERSTANDING OF ARTIODACTYL SOCIAL EVOLUTION By Monica Irene Miles Loren D. Hayes Hope Klug Associate Professor of UC Foundation Associate Professor of Biology, Geology, and Environmental Science Biology, Geology, and Environmental Science (Chair) (Committee Member) Timothy Gaudin UC Foundation Professor of Biology, Geology, and Environmental Science (Committee Member) ACCOUNTING FOR INTRASPECIFIC VARIATION TRANSFORMS OUR UNDERSTANDING OF ARTIODACTYL SOCIAL EVOLUTION By Monica Irene Miles A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of Science: Environmental Science The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Chattanooga, Tennessee December 2018 ii Copyright © 2018 By Monica Irene Miles All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT A major goal in the study of mammalian social systems has been to explain evolutionary transitions in social traits. Recent comparative analyses have used phylogenetic reconstructions to determine the evolution of social traits but have omitted intraspecific variation in social organization (IVSO) and mating systems (IVMS). This study was designed to summarize the extent of IVSO and IVMS in Artiodactyla and Perissodactyla, and determine the ancestral social organization and mating system for Artiodactyla. Some 82% of artiodactyls showed IVSO, whereas 31% exhibited IVMS; 80% of perissodactyls had variable social organization and only one species showed IVMS. The ancestral population of Artiodactyla was predicted to have variable social organization (84%), rather than solitary or group-living. A clear ancestral mating system for Artiodactyla, however, could not be resolved. These results show that intraspecific variation is common in artiodactyls and perissodactyls, and suggest a variable ancestral social organization for Artiodactyla. -

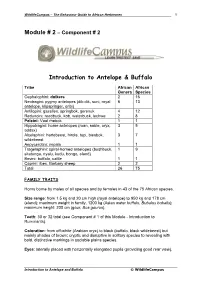

Introduction to Antelope & Buffalo

WildlifeCampus – The Behaviour Guide to African Herbivores 1 Module # 2 – Component # 2 Introduction to Antelope & Buffalo Tribe African African Genera Species Cephalophini: duikers 2 16 Neotragini: pygmy antelopes (dik-dik, suni, royal 6 13 antelope, klipspringer, oribi) Antilopini: gazelles, springbok, gerenuk 4 12 Reduncini: reedbuck, kob, waterbuck, lechwe 2 8 Peleini: Vaal rhebok 1 1 Hippotragini: horse antelopes (roan, sable, oryx, 3 5 addax) Alcelaphini: hartebeest, hirola, topi, biesbok, 3 7 wildebeest Aepycerotini: impala 1 1 Tragelaphini: spiral-horned antelopes (bushbuck, 1 9 sitatunga, nyalu, kudu, bongo, eland) Bovini: buffalo, cattle 1 1 Caprini: ibex, Barbary sheep 2 2 Total 26 75 FAMILY TRAITS Horns borne by males of all species and by females in 43 of the 75 African species. Size range: from 1.5 kg and 20 cm high (royal antelope) to 950 kg and 178 cm (eland); maximum weight in family, 1200 kg (Asian water buffalo, Bubalus bubalis); maximum height: 200 cm (gaur, Bos gaurus). Teeth: 30 or 32 total (see Component # 1 of this Module - Introduction to Ruminants). Coloration: from off-white (Arabian oryx) to black (buffalo, black wildebeest) but mainly shades of brown; cryptic and disruptive in solitary species to revealing with bold, distinctive markings in sociable plains species. Eyes: laterally placed with horizontally elongated pupils (providing good rear view). Introduction to Antelope and Buffalo © WildlifeCampus WildlifeCampus – The Behaviour Guide to African Herbivores 2 Scent glands: developed (at least in males) in most species, diffuse or absent in a few (kob, waterbuck, bovines). Mammae: 1 or 2 pairs. Horns. True horns consist of an outer sheath composed mainly of keratin over a bony core of the same shape which grows from the frontal bones. -

Mixed-Species Exhibits with Pigs (Suidae)

Mixed-species exhibits with Pigs (Suidae) Written by KRISZTIÁN SVÁBIK Team Leader, Toni’s Zoo, Rothenburg, Luzern, Switzerland Email: [email protected] 9th May 2021 Cover photo © Krisztián Svábik Mixed-species exhibits with Pigs (Suidae) 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 3 Use of space and enclosure furnishings ................................................................... 3 Feeding ..................................................................................................................... 3 Breeding ................................................................................................................... 4 Choice of species and individuals ............................................................................ 4 List of mixed-species exhibits involving Suids ........................................................ 5 LIST OF SPECIES COMBINATIONS – SUIDAE .......................................................... 6 Sulawesi Babirusa, Babyrousa celebensis ...............................................................7 Common Warthog, Phacochoerus africanus ......................................................... 8 Giant Forest Hog, Hylochoerus meinertzhageni ..................................................10 Bushpig, Potamochoerus larvatus ........................................................................ 11 Red River Hog, Potamochoerus porcus ............................................................... -

Zambia Managing Water for Sustainable Growth and Poverty Reduction

A COUNTRY WATER RESOURCES ASSISTANCE STRATEGY FOR ZAMBIA Zambia Public Disclosure Authorized Managing Water THE WORLD BANK 1818 H St. NW Washington, D.C. 20433 for Sustainable Growth and Poverty Reduction Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized THE WORLD BANK Zambia Managing Water for Sustainable Growth and Poverty Reduction A Country Water Resources Assistance Strategy for Zambia August 2009 THE WORLD BANK Water REsOuRcEs Management AfRicA REgion © 2009 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org E-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgement on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete infor- mation to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA; telephone: 978-750-8400; fax: 978-750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com. -

Mammals, Birds, Herps

Zambezi Basin Wetlands Volume II : Chapters 3 - 6 - Contents i Back to links page CONTENTS VOLUME II Technical Reviews Page CHAPTER 3 : REDUNCINE ANTELOPE ........................ 145 3.1 Introduction ................................................................. 145 3.2 Phylogenetic origins and palaeontological background 146 3.3 Social organisation and behaviour .............................. 150 3.4 Population status and historical declines ................... 151 3.5 Taxonomy and status of Reduncine populations ......... 159 3.6 What are the species of Reduncine antelopes? ............ 168 3.7 Evolution of Reduncine antelopes in the Zambezi Basin ....................................................................... 177 3.8 Conservation ................................................................ 190 3.9 Conclusions and recommendations ............................. 192 3.10 References .................................................................... 194 TABLE 3.4 : Checklist of wetland antelopes occurring in the principal Zambezi Basin wetlands .................. 181 CHAPTER 4 : SMALL MAMMALS ................................. 201 4.1 Introduction ..................................................... .......... 201 4.2 Barotseland small mammals survey ........................... 201 4.3 Zambezi Delta small mammal survey ....................... 204 4.4 References .................................................................. 210 CHAPTER 5 : WETLAND BIRDS ...................................... 213 5.1 Introduction ..................................................................