With an ALF Products Music Software System (Nine Voice) for Computer-Assisted Instruction in Composition Was Examined

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

People's Computer Company Jan-Feb 71 •

yolS no 4 People's Computer Company jan-feb 71 •.. ········CO"N·TENTS······························.. •· .. ·......... ...............................................·········· ··············iiii·yH·isTssuf· .. ·...... ············ .................................................................................• ............. , Subscription Information 2 Results of the pee Readerlhip Survey: Who We Are Come alld gel il,1 A jam-packed over-sized issue! Rulx;ts. Sat!!flites, spa,'(! games, 5 My Computer Uk .. Me even Better When We Hold Conversations . s/)(u'(! colullies, space ships, space out! Flllllrislic (('chllo/UKY Q/ld computers are another way of introducing children to programming aimosl iI/separable. Qllc/ we're just 011 the frulllien of exploratiun. Howabuut IIollle microcomputers linked Ilia public imerest satellite fo play Q I1l1lssive game 7 Crossword Punle Solution to design Qnd builcJ Q sfarship? Or what abmlf.. well, read the articles and let 8 A dly in the Ufe of eec .... inside a storefront computer installation us klluw your reactiuns' open to the publi(l 10 The Data Handler Usar', Manual ... a aerialized how·to for ulers of We 'n' lots uf educatiunal articles for all teachers Ihose in tile clilssruom as well as Ihe hume educaturs: see how 10 readl kids ",';11, COl/venatiUlUlI progrommillg 6502 microprocessors and Do" InnUlI! 's {rullt-o{-a-series uf how-lU articles all Ihe 6502-basecl Dala 12 Calculator Calculus _. _ a classroom revolution Handler. Severo' u{ the edlu-ariullal articles will be Ile/pflll hOlh 10 begillllers 13 Kalculator Korner ... problems and tricks alld alsu those wllo teadl begillllers. 14 Tinv BASIC ... an introduction for beginners And there's more. mure. more: sumething {ur evcryone: games listings, calcu 17 REVERSE •.. a game to turn you around lator arricles, Till)' wl/guages. -

While the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photograph And

INFORMATION TO USERS While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. For example: • Manuscript pages may have indistinct print. In such cases, the best available copy has been filmed. • Manuscripts may not always be complete. In such cases, a note will indicate that it is not possible to obtain missing pages. • Copyrighted material may have been removed from the manuscript. In such cases, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is also filmed as one exposure and is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 35mm slide or as a 17”x 23” black and white photographic print. Most photographs reproduce acceptably on positive microfilm or microfiche but lack the clarity on xerographic copies made from the microfilm. For an additional charge, 35mm slides of 6”x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography. 8703629 Whiston, Sandra Kristine THE DEVELOPMENT OF MELODIC CONCEPTS IN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL AGE CHILDREN USING COMPUTER-ASSISTED INSTRUCTION AS A SUPPLEMENTAL TOOL The Ohio State University Ph.D. 1986 University Microfilms International 300 N. Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106 PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. -

ALF MC1 Brochure

APPLE ][' COMPATIB LE ALFProductslnc. 1448 Estes Denver, CO 80215 APPLE MUSIC ]t D *r", o J J .t .F.F-F. , ilhh* € rns o:L tt: * f T T 1''IEASURE 3 SUB 6 9474 FREE EHD sAUEI APPLE II COMPUTER ENTER THE EXCITING follow the simple instructions in available.) FIELD OF COMPUTER our detailed manual. MUSIC THE SYNTHESIZER INSTALLATION CARD Now you can get into the exciting f ield of computer-controlled The Apple Music Jt plugs into any The Apple Music J[ synthesizer music at our lowest price ever. expansion slot in your Apple. The has nine independent "voices". For less than $22 per voice, the audio cable provided attaches to Each voice can play a melody Apple Music l[ is ideal for getting the synthesizer card and plugs like you could play on a piano started. lt comes with complete into your home stereo system. using only one finger. Using software for an Apple J["or Apple lnstallation is that easy. When several voices adds more l[-Plus* computer in just you "boot" the Disk 1[-compatible "fingers". Three of the nine minutes you can play the sample software disk, the start-up pro- voices play through the left songs provided. You can enter gram will automatically configure speaker of your stereo system. songs yourself from standard the software to work with the ex- Three other voices play through sheet music and play them using pansion slot you you've selected. the right speaker. The remaining the Entry program provided. Just (Cassette sof tware is also three voices play through both speakers to create a "middle" read special notations. -

Washington Apple Pi Journal, Decemver 1985

$2 Wa/hington Apple Pi The Journal of Washington8 Apple Pi, Ltd. Volume. 7 Devember 1985 number12 Hiahliahtl- - Macintosh Wizardry Dos & Don'ts of Spreadsheeting: Part 2 Word Perfect & Perfect All Word Processing Molecular Biology on the Macintosh Ten Tips for Using MacWrite In This Issue... Officers &Staff, Editorial 3 Lap Computers: Part 2 George Kinal 34 President's Corner • Tom Warrick 4 Letter to the Editor • 35 Event Queue, General Info, Job Mart, Classifieds. 5 A List Formatter for All People •• Ken Knight 36 WAP Calendar, SigNews • 6 Editing Applesoft Lines •• El i Argon 40 Neeting Reports Adrien Youell 7 Step-Trace for Forth Chester H. Page 42 WAP Hotline • 8 WordPerfect: Perfect WP Walton Francis 44 Apple III SIG News • Charl ene Ryan 9 Diagramless XWDs with Editor. .Richard Fitzhugh 48 Apple /II News David Ottalini 10 An AppleWorks-Ramworks Limitation .Fred Edwards 49 Minutes • 10 Book Reviews • • • • Robert C. Platt 50 Apple III Bib. of Open Apple Gaz. David Ottalini 11 How Do You Store Diskettes? • Merle Block 50 WAP Bulletin Board Systems 11 Best of Apple Items from UBBS Euclid Coukouma 51 Disk III Write Protect Bypass Ed ' Gooding 14 Frederick Apple Core • 54 EdSIG News •• • Jean Thomas 15 Molecular Biology on the Mac Peter Markiewicz 54 Q &A • • .Bruce F. Field 16 A 1200-Baud Modem for $175 • Lynn R. Trusal 55 Pie Ala Mode Slice Tom Kroll 17 Mac Q & A •• • Jonathan E. Hardis 56 GAMESIG News •• •• Barry Bedrick 18 MacNovice Ralph Begleiter 62 GAMESIG Suggestions for Santa Steven Payne 18 Professional Composer: A Review • D. -

ED 192Ale IR 000 906 AUTHOR () Frederick, Franz 4

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 192ale IR 000 906 AUTHOR () Frederick, Franz 4. TITLE Guide to Microcomputers. INSTITUTION Association for Educational Communications and Technology, Washington, D.C.: ERIC Clearinghouse on Information Resources, Syracuse, N.Y. SPONS AGENCY National Inst. of Education (DHEW), Washington, D.C. EEPORT NO ISBN-0-89240-030-2 PUB LATE SO CONTRACT 400-77-0015 NOTE 159p. AVAILABLE PRCMAECT Publications Sales, 1126 16th Street NW, Washington, DC 20036 ($9.50/AECT members: $11,50/non-members). TDES PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Computer Assisted Instruction: Computer Graphics: *Computer Managed Instruction: Equipment Maintenance: *Microcomputers: *Minicomputers: *Programing Languages: Videodisc Recordings ABSTRACT This comprehensive guide to microcomputers and their role Ln education discusses the general nature of microcomputers: computer languages in simple English: operating systems and what they can do for you: compatible systems: special accessories: service and maintenance: computer assisted instruction, computer managed instruction, and computer graphics: time sharing and resource sharing: Potential instructional and media center applications: and special applications, e.g., eleqtronic mail, networks, and videodiscs. Available resources are presented in a bibliography of magazines and journals about microcomputers and software and their uses, a selected list of companies specializing in creating specialized languages and applications programs for microcomputers, and a selected list of companies specializing in the preparation of educational programs for use on microcomputers. (CNC) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS ari the best that can be made * * from the original document,. *********************.************************************************* U S010Ail1iNtNIOF HEALTH. ltOUCAt*ON VOW AN' 14A t ioNat. INSSIFUlt OF IOUCAtiON o,M0 Nt 1, A'. It( 11.Nf 1,141, 1 IMP,A OW (IIM A /y WI I ly. -

Softalk Magazine, V.1.03, November 1980

This “quick, dirty, and compact” (QDC) edition of the November 1980 issue of Softalk magazine (Vol. 1 No. 3) was created by and is made freely available by The Softalk Apple Project (www.SoftalkApple.com). We thank fellow Friend of Softalk Bob Murphy for providing the loan of his issue for scanning by the project. For other PDFs of whole issues and sample pages, go to the Issue Profiles section of the project website. For more on the “preserve, explore, extend” mission of The Softalk Apple Project, go to: www.SoftalkApple.com/about Thank you… Enjoy! --Jim Salmons-- Founder and Research Director The Softalk Apple Project ' m t < j A g L VOLUME 1 NOVEMBER 1980 IN U T O n A Music Systems Exec Mountain I Bestsellers Autumn Leitmotif: The Musical Apple Meet IMP 2, the stylish impact printer with intelligent APPLE interface for HIRES and R\SCAL — $895. Designed for desk top use, this sleek unit combines for just about any system — high speed serial, Apple, an ultra-low profile with a unique fan-cooled printing Pet, TRS-80, IEEE 488... you name it. system that can knock out 80, 96, or 132 columns of Versatile character sets. 96 ASCII character set is crisp hardcopy with continuous throughput of one line standard. And you can select six character sizes, even per second. graphics, under software control. Options include full Three way paper handling. IMP 2 features three way page buffering and special character sets. paper handling for forms, single sheets and paper rolls, Service — a big difference. No other printer with tractors adjustable from 1.5 inch to 91/2 inches. -

Ed 284 542 Author Title Institution Spons Agency

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 284 542 IR 012 886 AUTHOR McLaughlin, Pamela TITLE Computer-Based Education: The Best of ERIC, 1983-1985. INSTITUTION ERIC Clearinghouse on Information Resources, Syracuse, N.Y. SPONS AGENCY Office of Edncational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. REPORT NO ISBN-0-937597-10-4 PUB DATE 86 CONTRACT 400-85-0001 NOTE 102p.; For the 1976-1982 edition, see ED 232 615. AVAILABLE FROM Information Resources Publications, Syracuse University, 030 Huntington Hall, Syracuse, NY 13244-2340 (IR-69, $10.00 plus shipping and handling). PUB TYPE Information Analyses - ERIC Information Analysis Products (071) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; *Computer Assisted Instruction; *Computer Managed Instruction; *Computers; Computer Simulation; *Computer Software; Correctional Education; Disabilities; Distance Education; Elementary Secondary Education; Futures (of Society); Inservice Teacher Education; Interactive Video; Material Development; Media Research; *Microcomputers; Technological Advancement IDENTIFIERS Courseware Evaluation ABSTRACT The fifth in a series of selected ERIC bibliographies on computer-based education begun in 1973, Computer-Based Education: The Best of ERIC, 1983-1985 provides citations and abstracts for over 250 documents selected from the more than 500 that were entered in the ERIC files over the three-year period. The emphasis in selection was on documents that focus broadly on the topic of computer-based education and provide -

Cgrs Microtech P.O

CGRS MICROTECH P.O. Box 368 SOUTHAMPTOM, PA. 18966 (215) 757-0284 NEW RELEASE A LOT OF I/O - A SINGLE I/O CARD FOR THE S100 BUS CONTAINS: 4 PROGRAMMABLE PARALLEL PORTS, 2 DUPLEX SERIAL PORTS, BAUD RATE GENERATOR, 2 - 16 BIT PROGRAMMABLE INTERVAL TIMERS, ROOM FOR UP TO l6K OF EPROM (2708,2716,2732), AND A CONNECTOR TO ADAPT THE PERCI 1070 INTELLIGENT FLOPPY DISK CONTROLLER TO THE S100 BUS. THIS SINGLE CARD CAN INTERFACE CRT TERMINALS, KEYBOARDS, PRINTERS, PAPER TAPE READERS, EPROM PROGRAMMERS, UP TO FOUR FLOPPY DISK DRIVES (WITH CONTROLLER) AND STILL PROVIDE EPROM SPACE AND 2 - 16 BIT TIMERS. THE "FLOPPY I/O" CARD FROM CGRS MICROTECH IS COMPATIBLE WITH ALTAIR 8800, IMSAI 8080 AND THE CGRS 6502/S100 MPU. THE "FLOPPY I/O" IS AVAILABLE IN KIT FORM ($169-95) AND ASSEMBLED ($219.95). PETEX-PET TO S100 ADAPTOR NEW PRODUCT INFORMATION CGRS MICROTECH, INC. ANNOUNCES THE PET/S100 ADAPTOR. CGRS,THE 6502/S100 EXPERTS, HAVE DEVELOPED AN ADAPTOR CARD THAT WILL CONVERT THE "MEMORY EXPANSION" CONNECTOR FROM THE PET COMPUTER TO THE S100 BUS. WITH THIS CARD THE OWNERS OF THE PET COMPUTER CAN EXPAND MEMORY, ADD I/O DEVICES (PRINTERS, FLOPPY DISC,ETC.) AND ENJOY THE ADVANTAGES OF THE NUMEROUS S100 PRODUCTS. THE PET/S100 IS A SINGLE BOARD THAT PLUGS INTO A CARD SLOT OF ANY S100 MOTHERBOARD AND CONNECTS TO THE PET MEMORY EXPANSION CONNECTOR VIA A FLAT RIBBON CABLE. THE PET/S100 ADAPTOR CAN BE USED TO ADAPT THE KIM, THE MOTOROLA EVII, AND OTHER6502 OR 6800 COMPUTERS TO THE S100 BUS USING THE APPROPRIATE CONNECTOR CABLE. -

REPORT NO 0-8011-0659-1 PUB DATE 87 NOTE 82P.; Guide

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 289 482 IR 012 949 TITLE The 1987 Educational Software Preview Guide. INSTITUTION Educational Software Evaluation Consortium, Menlo Park, CA. SPONS AGENCY California State Dept. of Education, Sacramento. REPORT NO 0-8011-0659-1 PUB DATE 87 NOTE 82p.; Guide developed at the California TECC Software Evaluation Forum (Menlo Park, CA, December 1-5, 1986) and funded through the California Teacher Education and Computer Center (TECC) program. For previous year's guide, see ED 242 338. AVAILABLE FROMPublication Sales, California State Department of Education, P.O. Box 271, Sacramento, CA 95802-0271 ($2.00). PUB TYPE Guides - Non-Classroom Use (055) Book/Product Reviews (072) EDRS PINCE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Authoring Aids (Programing); Computer Graphics; Computer Software Reviews; *Courseware; Elementary Secondary Education; Language Arts; Material Development; *Microcomputers; Science Instruction; Second Language Instruction; Social Sciences; Word Processing IDENTIFIERS *Education Software Evaluation Consortium; Spreadsheets ABSTRACT Developed to help educators locate computer software programs they may want to preview for students in K-12, this guide lists commercially available programs that have been favorably reviewed by members of the Educational Software Evaluation Consortium. ?rograms are listed alphabetically by title within curriculum areas: art; business education (accounting/bookkeeping, economics, typing); computers (awareness, programming/science, programming languages); -

Apple II-Iie-Iic Expansion Guide 1985.Pdf

. ; . ·~ -;:.· ) ' APPLE® 11/lle/llc ; EXPANSION GUIDE GARY PHILLIPS & MICHAEL FISHER APPLE® 11/lle/llc EXPANSION GUIDE GARY PHILLIPS & MICHAEL FISHER Also by the Author from TAB Books, Inc. No. 1961 Commodore 64™ Expansion Guide FIRST EDITION FIRST PRINTING Copyright © 1985 by TAB BOOKS INC. Printed In the United States of America Reproduction or publication of the content In any manner, without express permission of the publisher, Is prohibited. No liability Is assumed with respect to the use of the information herein. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Phillips, Gary. Applelll//e/llc expansion guide. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Expansion boards (Microcomputers) 2. Apple computer. I. Title. TK7895.E96P45 1985 001.64 85-7991 ISBN 0-8306-0901-6 ISBN 0-8306-1901·1 (pbk.) Front cover photos courtesy of Apple Computer, Inc. Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction X Chapter 1 Price, Performance, and Quality 1 Interfaces and Expansion Hardware 1 Reviews 2 Different Systems for Different Purposes 2 Chapter 2 The Apple II Family 4 Family Members 5 Peripherals 9 Chapter 3 Apple Hardware Shopper's Guide 11 Smart Shopping at Retail Stores 11 Smart Mall-Order Shopping 12 Smart Shopping at Computer Fairs 13 Smart Shopping for Used Equipment 13 Chapter 4 Methods of Evaluation and the Selection Process 15 Background Information 15 Reviews: Methods of Evaluation 15 A to D Rating System and List of Features 16 Selection of Products for Review 16 The Five Criteria Used in Evaluating Products-Structure of the Reviews-Groups of -

Music Entry System

APPLE I[' COM PATIB LE ALFProductslnc. 1448 Estes Denver, CO 80215 MUSIC ENTRY SYSTEM REsr (? J J .f''.F.F.h., il b h *,n,0..,,. E T - I IIERSURE SUB A 9474 FREE END SAUES song and play it. Since mistakes can paddles" which resemble the control- A STAR IS BORN be corrected easily and without diffi- lers for the popular "pong" television Early in 1979, ALF Products unleashed culty, there's no need for practice; an games. Each paddle has a knob and a a new music entry system on an un- entered song can be played time and button. Using these simple game suspecting personal-computer world. time again, flawlessly, at any tempo. paddles, and the Apple's built-in type- The heart of this new system was a Yet that's not all. lmprovements, chang- writer-like keyboard, you quickly and very sophisticated program named es, and even whole new voices can be easily select the various functions ENTRY. Taking a bold step into unique added at any time. available in the ENTRY program. innovations, ALF showed that music THE APPLE II COMPUTER programming could be done more JUST LIKE SHEET MUSIC personal easily than ever before. The Apple ll computer is the Programming a song with ENTRY is most popular internally-expandable amazingly easy. The Apple's television ALF: THE LEADER IN home computer available today. That's display shows the familiar staffs of COMPUTER MUSIC why ALF chose to create ENTRY for conventional sheet music. Across the Today, ALF's ENTRY program is being use with the Apple. -

I I I I I I I Memo~ I L ~

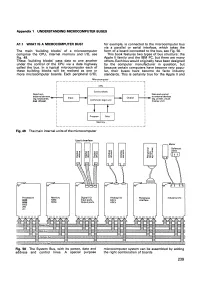

Appendix 1 UNDERSTANDING MICROCOMPUTER BUSES A1.1 WHAT IS A MICROCOMPUTER BUS? for example, is connected to the microcomputer bus via a parallel or serial interface, which takes the The main 'building blocks' of a microcomputer form of a board connected to the bus, see Fig. 50. comprise the CPU, internal memory and I/O, see This book features two types of bus structure: the Fig. 49. Apple II family and the IBM PC, but there are many These 'building blocks' pass data to one another others. Each bus would originally have been designed under the control of the CPU via a data highway by the computer manufacturer in question, but called the bus. In a typical microcomputer each of because certain computers have become very popu these building blocks will be realised as one or lar, their buses have become de facto industry more microcomputer boards. Each peripheral (I/O), standards. This is certainly true for the Apple II and Microcomputer 1---------------------------, I CPU I I I I Control block I Data from Data and control external devices I I to external devices (eg. keyboards, (eg. printer, visual disk drives) I display unit) I I I I I I I Memo~ I L ~ Fig.49 The main internal units of the microcomputer User's Interface Motor Solenoid C)CI) o~ valve -Q)co> ~~ Processors Memo~ Digital 110 Analog 110 Peripheral Industrial 1/0 8088 RAM Input ports DACs interface 8086 ROM Output ports ADCs 6502 280 etc. Fig. 50 The System Bus, with its power, data and microcomputer system can be assembled by adding address and control lines.