Power and Responsibility in Chinese Foreign Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Powerful patriots : nationalism, diplomacy, and the strategic logic of anti-foreign protest Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9z19141j Author Weiss, Jessica Chen Publication Date 2008 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Powerful Patriots: Nationalism, Diplomacy, and the Strategic Logic of Anti-Foreign Protest A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Jessica Chen Weiss Committee in charge: Professor David Lake, Co-Chair Professor Susan Shirk, Co-Chair Professor Lawrence Broz Professor Richard Madsen Professor Branislav Slantchev 2008 Copyright Jessica Chen Weiss, 2008 All rights reserved. Signature Page The Dissertation of Jessica Chen Weiss is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2008 iii Dedication To my parents iv Epigraph In regard to China-Japan relations, reactions among youths, especially students, are strong. If difficult problems were to appear still further, it will become impossible to explain them to the people. It will become impossible to control them. I want you to understand this position which we are in. Deng Xiaoping, speaking at a meeting with high-level Japanese officials, including Ministers of Foreign Affairs, Finance, Agriculture, and Forestry, June 28, 19871 During times of crisis, Arab governments demonstrated their own conception of public opinion as a street that needed to be contained. Some even complained about the absence of demonstrators at times when they hoped to persuade the United States to ease its demands for public endorsements of its policies. -

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

Elite Politics and the Fourth Generation of Chinese Leadership

Elite Politics and the Fourth Generation of Chinese Leadership ZHENG YONGNIAN & LYE LIANG FOOK* The personnel reshuffle at the 16th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party is widely regarded as the first smooth and peaceful transition of power in the Party’s history. Some China observers have even argued that China’s political succession has been institutionalized. While this paper recognizes that the Congress may provide the most obvious manifestation of the institutionalization of political succession, this does not necessarily mean that the informal nature of politics is no longer important. Instead, the paper contends that Chinese political succession continues to be dictated by the rule of man although institutionalization may have conditioned such a process. Jiang Zemin has succeeded in securing a legacy for himself with his “Three Represents” theory and in putting his own men in key positions of the Party and government. All these present challenges to Hu Jintao, Jiang’s successor. Although not new to politics, Hu would have to tread cautiously if he is to succeed in consolidating power. INTRODUCTION Although the 16th Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Congress ended almost a year ago, the outcomes and implications of the Congress continue to grip the attention of China watchers, including government leaders and officials, academics and businessmen. One of the most significant outcomes of the Congress, convened in Beijing from November 8-14, 2002, was that it marked the first ever smooth and peaceful transition of power since the Party was formed more than 80 years ago.1 Neither Mao Zedong nor Deng Xiaoping, despite their impeccable revolutionary credentials, successfully transferred power to their chosen successors. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 31 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 38 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 54 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 58 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 65 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 69 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

3/2006 Data Supplement PR China Hong Kong SAR Macau SAR Taiwan CHINA aktuell Journal of Current Chinese Affairs Data Supplement People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax:(040)4107945 Contributors: Uwe Kotzel Dr. Liu Jen-Kai Christine Reinking Dr. Günter Schucher Dr. Margot Schüller Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 3 The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 22 Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership LIU JEN-KAI 27 PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries LIU JEN-KAI 30 PRC Laws and Regulations LIU JEN-KAI 34 Hong Kong SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 36 Macau SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 39 Taiwan Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 41 Bibliography of Articles on the PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, and on Taiwan UWE KOTZEL / LIU JEN-KAI / CHRISTINE REINKING / GÜNTER SCHUCHER 43 CHINA aktuell Data Supplement - 3 - 3/2006 Dep.Dir.: CHINESE COMMUNIST Li Jianhua 03/07 PARTY Li Zhiyong 05/07 The Main National Ouyang Song 05/08 Shen Yueyue (f) CCa 03/01 Leadership of the Sun Xiaoqun 00/08 Wang Dongming 02/10 CCP CC General Secretary Zhang Bolin (exec.) 98/03 PRC Hu Jintao 02/11 Zhao Hongzhu (exec.) 00/10 Zhao Zongnai 00/10 Liu Jen-Kai POLITBURO Sec.-Gen.: Li Zhiyong 01/03 Standing Committee Members Propaganda (Publicity) Department Hu Jintao 92/10 Dir.: Liu Yunshan PBm CCSm 02/10 Huang Ju 02/11 -

International Security 24:1 66

China’s Search for a John Wilson Lewis Modern Air Force and Xue Litai For more than forty- eight years, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has sought to build a combat-ready air force.1 First in the Korean War (1950–53) and then again in 1979, Beijing’s leaders gave precedence to this quest, but it was the Gulf War in 1991 coupled with growing concern over Taiwan that most alerted them to the global revolution in air warfare and prompted an accelerated buildup. This study brieºy reviews the history of China’s recurrent efforts to create a modern air force and addresses two principal questions. Why did those efforts, which repeatedly enjoyed a high priority, fail? What have the Chinese learned from these failures and how do they deªne and justify their current air force programs? The answers to the ªrst question highlight changing defense con- cerns in China’s national planning. Those to the second provide a more nu- anced understanding of current security goals, interservice relations, and the evolution of national defense strategies. With respect to the ªrst question, newly available Chinese military writings and interviews with People’s Liberation Army (PLA) ofªcers on the history of the air force suggest that the reasons for the recurrent failure varied markedly from period to period. That variation itself has prevented the military and political leaderships from forming a consensus about the lessons of the past and the policies that could work. In seeking to answer the second question, the article examines emerging air force and national defense policies and doctrines and sets forth Beijing’s ra- tionale for the air force programs in light of new security challenges, particu- larly those in the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea. -

LE 19Ème CONGRÈS DU PARTI COMMUNISTE CHINOIS

PROGRAMME ASIE LE 19ème CONGRÈS DU PARTI COMMUNISTE CHINOIS : CLÔTURE SUR L’ANCIEN RÉGIME ET OUVERTURE DE LA CHINE DE XI JINPING Par Alex PAYETTE STAGIAIRE POSTDOCTORAL POUR LE CONSEIL CANADIEN DE RECHERCHES EN SCIENCES HUMAINES CHERCHEUR À L’IRIS JUIN 2017 ASIA FOCUS #46 l’IRIS ASIA FOCUS #46 - PROGRAMME ASIE / Octobre 2017 e 19e Congrès qui s’ouvrira en octobre prochain, soit quelques semaines avant la visite de Donald Trump en Chine, promet de consolider la position de Xi Jinping dans l’arène politique. Travaillant d’arrache-pied depuis 2013 à se débarrasser L principalement des alliés de Jiang Zemin, l’alliance Xi-Wang a enfin réussi à purger le Parti-État afin de positionner ses alliés. Ce faisant, la transition qui aura vraiment lieu cet automne n’est pas la transition Hu Jintao- Xi Jinping, celle-ci date déjà de 2012. La transition de 2017 est celle de la Chine des années 1990 à la Chine des années 2010, soitde la Chine de Jiang Zemin à celle de Xi Jinping. Ce sera également le début de l’ère des enfants de la révolution culturelle, des « zhiqing » [知青] (jeunesses envoyées en campagne), qui formeront une majorité au sein du Politburo et qui remanieront la Chine à leur manière. Avec les départs annoncés, Xi pourra enfin former son « bandi » [班底] – garde rapprochée – au sein du Politburo et effectivement mettre en place un agenda de politiques et non pas simplement des mesures visant à faire le ménage au cœur du Parti-État. Des 24 individus restants, entre 12 et 16 devront partir; 121 sièges (si l’on compte le siège rendu vacant de Sun Zhengcai) et 16 si Xi Jinping décide d’appliquer plus « sévèrement » la limite d’âge maintenant à 68 ans. -

China's NOTES from the EDITORS 4 Who's Hurting Who with National Culture

—Inspired by the Lei Feng* spirit of serving the people, primary school pupils of Harbin City often do public cleanups on their Sunday holidays despite severe winter temperature below zero 20°C. Photo by Men Suxian * Lei Feng was a squad leader of a Shenyang unit of the People's Liberation Army who died on August 15, 1962 while on duty. His practice of wholeheartedly serving the people in his ordinary post has become an example for all Chinese people, especially youfhs. Beijing««v!r VOL. 33, NO. 9 FEB. 26-MAR. 4, 1990 Carrying Forward the Cultural Heritage CONTENTS • In a January 10 speech. CPC Politburo member Li Ruihuan stressed the importance of promoting China's NOTES FROM THE EDITORS 4 Who's Hurting Who With national culture. Li said this will help strengthen the coun• Sanctions? try's sense of national identity, create the wherewithal to better resist foreign pressures, and reinforce national cohe• EVENTS/TRENDS 5 8 sion (p. 19). Hong Kong Basic Law Finalized Economic Zones Vital to China NPC to Meet in March Sanctions Will Get Nowhere Minister Stresses Inter-Ethnic Unity • Some Western politicians, in defiance of the reahties and Dalai's Threat Seen as Senseless the interests of both China and their own countries, are still Farmers Pin Hopes On Scientific demanding economic sanctions against China. They ignore Farming the fact that sanctions hurt their own interests as well as 194 AIDS Cases Discovered in China's (p. 4). China INTERNATIONAL Upholding the Five Principles of Socialism Will Save China Peaceful Coexistence 9 Mandela's Release: A Wise Step o This is the first instalment of a six-part series contributed Forward 13 by a Chinese student studying in the United States. -

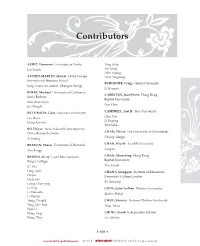

Contributors.Indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM F-479 /203/BER00069/Work/Indd/%20Backmatter

02_Contributors.indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM f-479 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter Contributors AUBIÉ, Hermann University of Turku Yang Jiang Liu Xiaobo Yao Ming Zhao Ziyang AUSTIN-MARTIN, Marcel China Europe Zhou Youguang International Business School BURGDOFF, Craig Capital University Jiang Zemin (co-author: Zhengxu Wang) Li Hongzhi BERRY, Michael University of California, CABESTAN, Jean-Pierre Hong Kong Santa Barbara Baptist University Hou Hsiao-hsien Lien Chan Jia Zhangke CAMPBELL, Joel R. Troy University BETTINSON, Gary Lancaster University Chen Yun Lee, Bruce Li Keqiang Wong Kar-wai Wen Jiabao BO Zhiyue New Zealand Contemporary CHAN, Felicia The University of Manchester China Research Centre Cheung, Maggie Xi Jinping BRESLIN, Shaun University of Warwick CHAN, Hiu M. Cardiff University Zhu Rongji Gong Li BROWN, Kerry Lau China Institute, CHAN, Shun-hing Hong Kong King’s College Baptist University Bo Yibo Zen, Joseph Fang Lizhi CHANG Xiangqun Institute of Education, Hu Jia University College London Hu Jintao Fei Xiaotong Leung Chun-ying Li Peng CHEN, Julie Yu-Wen Palacky University Li Xiannian Kadeer, Rebiya Li Xiaolin Tsang, Donald CHEN, Szu-wei National Taiwan University Tung Chee-hwa Teng, Teresa Wan Li Wang Yang CHING, Frank Independent Scholar Wang Zhen Lee, Martin • 569 • www.berkshirepublishing.com © 2015 Berkshire Publishing grouP, all rights reserved. 02_Contributors.indd Page 570 9/22/15 12:09 PM f-500 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter • Berkshire Dictionary of Chinese Biography • Volume 4 • COHEN, Jerome A. New -

The Collection and Digitization of the Genealogies in the National Library of China

Submitted on: June 24, 2013 The Collection and Digitization of the Genealogies in the National Library of China Xie Dongrong National Library of China, Beijing, China. Xiao Yu National Library of China, Beijing, China. Shi Jian National Library of China, Beijing, China. Copyright © 2013 by Xie Dongrong, Xiao Yu and Shi Jian. This work is made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Abstract: The history of the genealogies collection of NLC has been reviewed and the current situation of the collection is introduced as well. The character and value of the genealogies in NLC is analyzed and the digitalization of the collections in different levels is emphasized including the various services to the readers basing on these digital products. 1) The genealogies have been catalogued in MARC format and the fundamental information of the collections is described. 2) The images of the original genealogies are acquired by scanning or photographing, which are provided to the readers with the cataloging data and the volumes information of the genealogies. 3) The genealogies have been indexed, the indexes to the titles and family members are focused on which described the information of the peoples and articles in the documents that can be used separately or accompanying with the images. 4) The images are transformed into the text format and the full text search can be achieved. 5) The people relations in the pedigrees in the genealogies are sorted out and the data of the family trees is acquired. The readers can search the database by people relation and specify the searching result. -

PLACE and INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZA TIONS INDEX Italicised Page Numbers Refer to Extended Entries

PLACE AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZA TIONS INDEX Italicised page numbers refer to extended entries Aachcn, 549, 564 Aegean North Region. Aktyubinsk, 782 Alexandroupolis, 588 Aalborg, 420, 429 587 Akure,988 Algarve. 1056, 1061 Aalst,203 Aegean South Region, Akureyri, 633, 637 Algeciras, I 177 Aargau, 1218, 1221, 1224 587 Akwa Ibom, 988 Algeria, 8,49,58,63-4. Aba,988 Aetolia and Acarnania. Akyab,261 79-84.890 Abaco,178 587 Alabama, 1392, 1397, Al Ghwayriyah, 1066 Abadan,716-17 Mar, 476 1400, 1404, 1424. Algiers, 79-81, 83 Abaiang, 792 A(ghanistan, 7, 54, 69-72 1438-41 AI-Hillah,723 Abakan, 1094 Myonkarahisar, 1261 Alagoas, 237 AI-Hoceima, 923, 925 Abancay, 1035 Agadez, 983, 985 AI Ain. 1287-8 Alhucemas, 1177 Abariringa,792 Agadir,923-5 AlaJuela, 386, 388 Alicante, 1177, 1185 AbaslUman, 417 Agalega Island, 896 Alamagan, 1565 Alice Springs, 120. Abbotsford (Canada), Aga"a, 1563 AI-Amarah,723 129-31 297,300 Agartala, 656, 658. 696-7 Alamosa (Colo.). 1454 Aligarh, 641, 652, 693 Abecbe, 337, 339 Agatti,706 AI-Anbar,723 Ali-Sabieh,434 Abemama, 792 AgboviIle,390 Aland, 485, 487 Al Jadida, 924 Abengourou, 390 Aghios Nikolaos, 587 Alandur,694 AI-Jaza'ir see Algiers Abeokuta, 988 Agigea, 1075 Alania, 1079,1096 Al Jumayliyah, 1066 Aberdeen (SD.), 1539-40 Agin-Buryat, 1079. 1098 Alappuzha (Aleppy), 676 AI-Kamishli AirpoI1, Aberdeen (UK), 1294, Aginskoe, 1098 AI Arish, 451 1229 1296, 1317, 1320. Agion Oras. 588 Alasb, 1390, 1392, AI Khari]a, 451 1325, 1344 Agnibilekrou,390 1395,1397,14(K), AI-Khour, 1066 Aberdeenshire, 1294 Agra, 641, 669, 699 1404-6,1408,1432, Al Khums, 839, 841 Aberystwyth, 1343 Agri,1261 1441-4 Alkmaar, 946 Abia,988 Agrihan, 1565 al-Asnam, 81 AI-Kut,723 Abidjan, 390-4 Aguascalientes, 9(X)-1 Alava, 1176-7 AlIahabad, 641, 647, 656. -

Understanding the Nuances of Waishengren History and Agency

China Perspectives 2010/3 | 2010 Taiwan: The Consolidation of a Democratic and Distinct Society Understanding the Nuances of Waishengren History and Agency Dominic Meng-Hsuan et Mau-Kuei Chang Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/5310 DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.5310 ISSN : 1996-4617 Éditeur Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Édition imprimée Date de publication : 15 septembre 2010 ISSN : 2070-3449 Référence électronique Dominic Meng-Hsuan et Mau-Kuei Chang, « Understanding the Nuances of Waishengren », China Perspectives [En ligne], 2010/3 | 2010, mis en ligne le 01 septembre 2013, consulté le 28 octobre 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/5310 ; DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.5310 © All rights reserved Special Feature s e v Understanding the Nuances i a t c n i e of Waishengren h p s c r History and Agency e p DOMINIC MENG-HSUAN YANG AND MAU-KUEI CHANG In the late 1940s and early 50s, the world witnessed a massive wave of political migrants out of Mainland China as a result of the Chinese civil war. Those who sought refuge in Taiwan with the KMT came to be known as the “mainlanders” or “ waishengren .” This paper will provide an overview of the research on waishengren in the past few decades, outlining various approaches and highlighting specific political and social context that gave rise to these approaches. Finally, it will propose a new research agenda based on a perspective of migration studies and historical/sociological analysis. The new approach argues for the importance of both history and agency in the study of waishengren in Taiwan.