The SADC Communications Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vodacom Annual Results Presentation

Vodacom Group Annual Results For the year ended 31 March 2020 The future is exciting. Ready? Disclaimer The following presentation is being made only to, and is only directed at, persons to whom such presentations may lawfully be communicated (‘relevant persons’). Any person who is not a relevant person should not act or rely on this presentation or any of its contents. Information in the following presentation relating to the price at which relevant investments have been bought or sold in the past or the yield on such investments cannot be relied upon as a guide to the future performance of such investments. This presentation does not constitute an offering of securities or otherwise constitute an invitation or inducement to any person to underwrite, subscribe for or otherwise acquire securities in any company within the Group. Promotional material used in this presentation that is based on pricing or service offering may no longer be applicable. This presentation contains certain non-GAAP financial information which has not been reviewed or reported on by the Group’s auditors. The Group’s management believes these measures provide valuable additional information in understanding the performance of the Group or the Group’s businesses because they provide measures used by the Group to assess performance. However, this additional information presented is not uniformly defined by all companies, including those in the Group’s industry. Accordingly, it may not be comparable with similarly titled measures and disclosures by other companies. Additionally, although these measures are important in the management of the business, they should not be viewed in isolation or as replacements for or alternatives to, but rather as complementary to, the comparable GAAP measures. -

From Telkom to Hellkom1: a Critical Reflection on the Current Telecommunication Policy in South Africa from a Social Justice Perspective

ARTICLE IN PRESS + MODEL The International Information & Library Review (2008) xx,1e7 available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/iilr To talk or not to talk? From Telkom to Hellkom1: A critical reflection on the current telecommunication policy in South Africa from a social justice perspective S.R. Ponelis a, J.J. Britz a,b,* a Department of Information Science, School of Information Technology, University of Pretoria, 0002 Pretoria, South Africa b School of Information Studies, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 3210 N, Maryland Avenue, Milwaukee WI 53211, United States KEYWORDS Abstract With the development of new information and communication technologies, the Telecommunications; right to communicate assumes new dimensions, since it is almost impossible to fully participate Right to communicate; in the globalized world without access to modern information and communication technolo- South Africa; gies. South Africa held its first democratic elections in 1994 and has subsequently returned Telkom; to the international arena. Its citizens should rightly expect to be able to participate in all that Social justice this return offers, not only politically, but also economically and socially. Telecommunications are vital to making such participation possible. In recognition of this fact, the newly elected government developed policies and enacted legislation to ensure that the telecommunications sector, and specifically the sole fixed line service provider Telkom, provides South African citi- zens affordable access to the telecommunications infrastructure whilst providing acceptable levels of service. However, rather than meeting its obligation to the government and the people of South Africa, Telkom has misused its monopoly. The social injustice that this situa- tion creates is critically examined against the background of the right to communicate based on Rawls’ principles of social justice and Sen’s capability approach. -

Jacaranda Fm in Essence

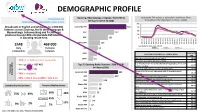

DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE Gauteng, Mpumalanga, Limpopo, North West Jacaranda FM enjoys a consistent audience flow JACARANDA FM Afrikaans LSM 8-10 (000) throughout the day (Mon to Sun) – (000) PERFORMANCE HIGHLIGHTS (Part 1 of 2) 200 Broadcasts in English and Afrikaans to 1 004 000 Jacaranda FM 366 150 listeners across Gauteng, North West, Limpopo & 100 Mpumalanga. Johannesburg and Pretoria are 947 247 pivotal areas and 84% of Jacaranda FM listeners 50 in Gauteng reside here. RSG 185 0 Metro FM 109 0100-0200 0200-0300 0300-0400 0400-0500 0500-0600 0600-0700 0700-0800 0800-0900 0900-1000 1000-1100 1100-1200 1200-1300 1300-1400 1600-1700 1700-1800 1800-1900 1900-2000 2100-2200 2300-2400 0000-0100 1400-1500 1500-1600 2000-2100 2200-2300 1h48 469 000 Ave Qhr by hr, Mon – Sun, ADULTS Daily Exclusive 702 88 M-F SAT SUN Listenership Listeners Jacaranda 5FM 80 LIFESTYLE STATEMENTS - AGREE WITH FM OFM 44 I am very conscious about my health 48.8% • 47% of individuals listen exclusively I consider my diet to be very healthy 43.4% It is important for me to include lots of vegetables, fruit and • Average HHI of R27 482 Top 10 Gauteng Radio Stations : SEM 8-10 & 63.4% salad in my diet Afrikaans (000) • Average age of 41 You can judge a person by the car they drive 44.0% Jacaranda FM 297 My car should be well equipped with all possible safety Exclusive 52.5% • 70% is employed features Listenership 947 257 My car should express my personality 48.8% • 63% in LSM 8-10 and 60% in SEM 9-10 Comfort is the most important thing in a car 51.6% RSG 138 I love to buy new gadgets and appliances 46.9% Metro FM 95 I do extensive research before purchasing an electronic Listenership by location Listenership by device 44.4% item. -

HOW to GUIDE Android Phones 1. Go to Settings on the Device. 2. Select “ Connections”, “Wireless & Networks” Or “N

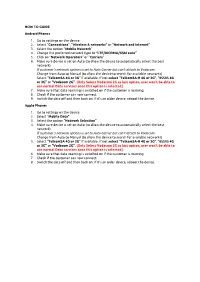

HOW TO GUIDE Android Phones 1. Go to settings on the device. 2. Select “Connections”, “Wireless & networks” or “Network and Internet” 3. Select the option “Mobile Network” 4. Change the preferred network type to “LTE/WCDMA/GSM auto” 5. Click on “Network Operators” or “Carriers” 6. Make sure device is set on Auto (to allow the device to automatically select the best network) If customer’s network options is set to Auto Carrier but can’t attach to Vodacom: Change from Auto to Manual (to allow the device to search for available networks) Select “TelkomSA 4G or 3G” if available. If not select “TelkomSA-R 4G or 3G”, “65505 4G or 3G” or “Vodacom 2G”. (Only Select Vodacom 2G as last option, user won’t be able to use normal Data services once this option is selected.) 7. Make sure that data roaming is switched on if the customer is roaming. 8. Check if the customer can now connect. 9. Switch the data off and then back on. If it’s an older device, reboot the device. Apple Phones 1. Go to settings on the device. 2. Select “Mobile Data” 3. Select the option “Network Selection” 4. Make sure device is set on Auto (to allow the device to automatically select the best network) If customer’s network options is set to Auto Carrier but can’t attach to Vodacom: Change from Auto to Manual (to allow the device to search for available networks) 5. Select “TelkomSA 4G or 3G” if available. If not select “TelkomSA-R 4G or 3G”, “65505 4G or 3G” or “Vodacom 2G”. -

An Assessment of Claims Regarding Health Effects of 5G Mobile Telephony Networks

An Assessment of Claims regarding Health Effects of 5G Mobile Telephony Networks C R Burger, Z du Toit, A A Lysko, M T Masonta, F Mekuria, L Mfupe, N Ntlatlapa and E Suleman Contact: Dr Moshe Masonta [email protected] 2020-05-11 Contents Preamble .............................................................................................................................. 2 1. Overview of 5G Networks .............................................................................................. 3 1.1 What are 5G networks? ............................................................................................... 3 1.2 What are the health effects of mobile networks? .......................................................... 6 1.3 What can we expect from 5G networks?...................................................................... 7 2. Summary Technical Data on 5G .................................................................................... 9 2.1 Which frequencies will be used for 5G in South Africa? .......................................... 9 2.2 A Brief Comparison of 4G and 5G ......................................................................... 11 3. Summary notes ............................................................................................................ 12 Preamble This document was produced by a team of researchers from the Next Generation Enterprises and Institutions, and Next Generation Health clusters of the CSIR. It is a response to media claims of links between 5G mobile telephone networks -

6. Market Distortions and Infrastructure Sharing

102959 world development report Public Disclosure Authorized BACKGROUND PAPER Digital Dividends The Economics and Policy Public Disclosure Authorized Implications of Infrastructure Sharing and Mutualisation in Africa Jose Marino Garcia Public Disclosure Authorized World Bank Group Tim Kelly World Bank Group Public Disclosure Authorized The economics and policy implications of infrastructure sharing and mutualisation in Africa Jose Marino Garcia [email protected] and Tim Kelly [email protected] November 2015 Table of contents Executive summary ......................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 2 2. Demand trends, new technologies and the impact on infrastructure sharing ........................ 4 3. Internet supply markets and the Internet Ecosystem .................................................................... 8 4. Analysis of infrastructure sharing models ..................................................................................... 11 5. The role of infrastructure sharing to reduce market and regulatory failures in the provision of broadband internet ........................................................................................................ 30 6. Market distortions and infrastructure sharing .............................................................................. -

Employment Equity Act (55/1998): 2019 Employment Equity Public Register in Terms of Section 41 43528 PUBLIC REGISTER NOTICE

STAATSKOERANT, 17 JULIE 2020 No. 43528 31 Employment and Labour, Department of/ Indiensneming en Arbeid, Departement van DEPARTMENT OF EMPLOYMENT AND LABOUR NO. 779 17 JULY 2020 779 Employment Equity Act (55/1998): 2019 Employment Equity Public Register in terms of Section 41 43528 PUBLIC REGISTER NOTICE EMPLOYMENT EQUITY ACT, 1998 (ACT NO. 55 OF 1998) I, Thembelani Thulas Nxesi, Minister of Employment and Labour, publish in the attached Schedule hereto, the register maintained in terms of Section 41 of the Employment Equity Act, 1998 (Act No. 55 of 1998) of designated employers that have submitted employment equity reports in terms of Section 21, of the Employment Equity Act, Act No. 55 of 1998 as amended. MR.lWNXESI, MP MINISTER OF EMPLOYMENT AND LABOUR ')..,6j oZ> do:2,"eJ 1/ ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ISAZISO SEREJISTA YOLUNTU UMTHETHO WOKULUNGELELANISA INGQESHO, (UMTHETHO YINOMBOLO YAMA-55 KA-1998) Mna, Thembelani Thulas Nxesi, uMphathiswa wezengqesho kanye nezabasebenzi, ndipapasha kule Shedyuli iqhakamshelwe apha, irejista egcina ngokwemiqathango yeCandelo 41 lomThetho wokuLungelelanisa iNgqesho, ka- 1998 (umThetho oyiNombolo yama-55 ka-1998) izikhundla zabaqeshi abangenise iingxelo zokuLungelelanisa iNgqesho ngokwemigaqo yeCandelo 21, lo mThetho wokulungelelanisa iNgqesho, umThetho oyiNombolo yama-55 ka- 1998. -6'';7MR.TW NXESI, MP UMPHATHISWA WEZENGQESHO KANYE NEZABASEBENZI 26/tJ :20;:J,()1/ This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za 32 No. 43528 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 17 JULY 2020 List of designated employers who reported for the 1 September 2019 reporting cycle Description of terms: No: This represents sequential numbering of designated employers & bears no relation to an employer. (The list consists of 5969 large employers & 21158 small employers). -

Mediaplay Fibre Frequently Asked Questions

MEDIAPLAY FIBRE FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS 1. What is MediaPlay Fibre? MediaPlay Fibre is a converged tariff plan offering uncapped Fibre, C-Fibre Connector mobile that’s inclusive of mobile voice, mobile data, mobile Wi-Fi calling benefits and BINGE Premium entertainment package on black with access to local and international movies, series, music videos, Kid's shows, documentaries and much more. 2. Where can I sign up for MediaPlay Fibre? MediaPlay Fibre is available through the following channels: Cell C Fibre Field sales team which you can email at [email protected]; Cell C Fibre Telesales team which you can contact on 084 135 or email at [email protected]; Through our online channel, namely online sales channel, which can be accessed at https://www.cellc.co.za/cellc/c-fibre; Cell C Business Sales Channel which you can contact on 084 194 4000 or email [email protected]; Through select Cell C owned and franchise stores, which can be viewed at https://www.cellc.co.za/cellc/c-fibre. 3. What are the benefits of the new MediaPlay Fibre plans? MediaPlay Fibre tariff plans provide subscribers with the following inclusive benefits; Unlimited, unrestricted and unshaped Fibre; C-Fibre Connector mobile offering; o 1000 Any-net voice minutes per SIM per month o 2GB of mobile data per SIM per month o Unlimited free black streaming data included on C-Fibre Connector Mobile until 10 November 2018 o 500 Any-net Wi-Fi calling minutes per SIM per month BINGE Premium entertainment package on black: with access to over 60 TV channels, local and international movies, series, music videos, kid’s shows, documentaries and much more. -

Chapter 11 ) INTELSAT

Case 20-32299-KLP Doc 495 Filed 07/09/20 Entered 07/09/20 15:11:39 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 16 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA RICHMOND DIVISION ) In re: ) Chapter 11 ) 1 INTELSAT S.A., et al., ) Case No. 20-32299 (KLP) ) Debtors. ) (Jointly Administered) ) DECLARATION OF DISINTERESTEDNESS OF HOGAN LOVELLS US LLP AS PROPOSED ORDINARY COURSE PROFESSIONAL I, Steven M. Kaufman, declare under penalty of perjury: 1. I am a Partner of Hogan Lovells US LLP, located at Columbia Square, 555 Thirteenth Street, NW, Washington, D.C. 2004 (“HLUS”). 2. Intelsat S.A. and its affiliates, as debtors and debtors in possession (collectively, the “Debtors”), have requested that HLUS continue to provide legal services to the Debtors as an ordinary course professional pursuant to section 327(e) of the Bankruptcy Code in the Debtors’ chapter 11 cases (collectively, the “Chapter 11 Cases”), and HLUS has agreed to provide such services. Such services may be provided by HLUS directly and/or through its affiliated businesses, including Hogan Lovells International LLP (collectively, the “Firm”), through arrangements with HLUS. 3. The Firm may have performed services in the past, may currently perform services, and may perform services in the future in matters unrelated to the Chapter 11 Cases for persons or entities that are parties in interest in the Chapter 11 Cases. See Schedule A attached 1 Due to the large number of Debtors in these Chapter 11 Cases, for which joint administration has been granted, a complete list of the Debtor entities and the last four digits of their federal tax identification numbers is not provided herein. -

Independent Communications Authority of South Africa Act: Discussion Document to Identify Priority Markets in Electronic Communi

4 No. 41446 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 16 FEBRUARY 2018 GENERAL NOTICES • ALGEMENE KENNISGEWINGS Independent Communications Authority of South Africa/ Onafhanklike Kommunikasie-owerheid van Suid-Afrika INDEPENDENT COMMUNICATIONS AUTHORITY OF SOUTH AFRICA NOTICE 71 OF 2018 71 Independent Communications Authority of South Africa (13/2000): Invitation for written representations on priority markets in the electronic communications sector 41446 This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za STAATSKOERANT, 16 FEBRUARIE 2018 No. 41446 5 INVITATION INVITATION REPRESENTATIONS FOR FOR WRITTEN ON ON PRIORITY PRIORITY MARKETS THE THE IN IN ELCTRONIC ELCTRONIC COMMUNICATIONS SECTOR June June 2017, Independent Communications the the On On 30 1. 1. Authority Authority of South Africa "the "the ( ( Gazette' Gazette' Authority Authority published published notice the ") ") in in indicating indicating conduct conduct Inquiry intention intention its its to to a a an an terms terms of section section 4B(1)(a) "the "the Inquiry") in in ( ( Authority Authority of of Independent Independent Communications the the of of of of (Act (Act "ICASA South South Africa 2000 2000 2000) Act, Act, No, No, 13 13 ( ( Act Act "). "). of of The The this this Inquiry to: to: is is 2. 2. purpose purpose identify identify markets markets electronic the the 2.1. 2.1. and in in segments segments communications communications or or ante ante sector sector that susceptible susceptible regulations; regulations; and and to to ex ex are are determine determine which of prioritised prioritised for these these markets should 2.2. 2.2. be be market market reviews and and terms terms of section 67(4) of Electronic potential potential regulation the the in in Communications Communications (Act (Act of of 2005) 2005) 2005 2005 "ECA Act, Act, No. -

A Channel Guide

Intelsat is the First MEDIA Choice In Africa Are you ready to provide top media services and deliver optimal video experience to your growing audiences? With 552 channels, including 50 in HD and approximately 192 free to air (FTA) channels, Intelsat 20 (IS-20), Africa’s leading direct-to- home (DTH) video neighborhood, can empower you to: Connect with Expand Stay agile with nearly 40 million your digital ever-evolving households broadcasting reach technologies From sub-Saharan Africa to Western Europe, millions of households have been enjoying the superior video distribution from the IS-20 Ku-band video neighborhood situated at 68.5°E orbital location. Intelsat 20 is the enabler for your TV future. Get on board today. IS-20 Channel Guide 2 CHANNEL ENC FR P CHANNEL ENC FR P 947 Irdeto 11170 H Bonang TV FTA 12562 H 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11514 H Boomerang EMEA Irdeto 11634 V 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11674 H Botswana TV FTA 12634 V 1485 Radio Today Irdeto 11474 H Botswana TV FTA 12657 V 1KZN TV FTA 11474 V Botswana TV Irdeto 11474 H 1KZN TV Irdeto 11594 H Bride TV FTA 12682 H Nagravi- Brother Fire TV FTA 12562 H 1KZN TV sion 11514 V Brother Fire TV FTA 12602 V 5 FM FTA 11514 V Builders Radio FTA 11514 V 5 FM Irdeto 11594 H BusinessDay TV Irdeto 11634 V ABN FTA 12562 H BVN Europa Irdeto 11010 H Access TV FTA 12634 V Canal CVV International FTA 12682 H Ackermans Stores FTA 11514 V Cape Town TV Irdeto 11634 V ACNN FTA 12562 H CapeTalk Irdeto 11474 H Africa Magic Epic Irdeto 11474 H Capricorn FM Irdeto 11170 H Africa Magic Family Irdeto -

Multiple Documents

Alex Morgan et al v. United States Soccer Federation, Inc., Docket No. 2_19-cv-01717 (C.D. Cal. Mar 08, 2019), Court Docket Multiple Documents Part Description 1 3 pages 2 Memorandum Defendant's Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Support of i 3 Exhibit Defendant's Statement of Uncontroverted Facts and Conclusions of La 4 Declaration Gulati Declaration 5 Exhibit 1 to Gulati Declaration - Britanica World Cup 6 Exhibit 2 - to Gulati Declaration - 2010 MWC Television Audience Report 7 Exhibit 3 to Gulati Declaration - 2014 MWC Television Audience Report Alex Morgan et al v. United States Soccer Federation, Inc., Docket No. 2_19-cv-01717 (C.D. Cal. Mar 08, 2019), Court Docket 8 Exhibit 4 to Gulati Declaration - 2018 MWC Television Audience Report 9 Exhibit 5 to Gulati Declaration - 2011 WWC TElevision Audience Report 10 Exhibit 6 to Gulati Declaration - 2015 WWC Television Audience Report 11 Exhibit 7 to Gulati Declaration - 2019 WWC Television Audience Report 12 Exhibit 8 to Gulati Declaration - 2010 Prize Money Memorandum 13 Exhibit 9 to Gulati Declaration - 2011 Prize Money Memorandum 14 Exhibit 10 to Gulati Declaration - 2014 Prize Money Memorandum 15 Exhibit 11 to Gulati Declaration - 2015 Prize Money Memorandum 16 Exhibit 12 to Gulati Declaration - 2019 Prize Money Memorandum 17 Exhibit 13 to Gulati Declaration - 3-19-13 MOU 18 Exhibit 14 to Gulati Declaration - 11-1-12 WNTPA Proposal 19 Exhibit 15 to Gulati Declaration - 12-4-12 Gleason Email Financial Proposal 20 Exhibit 15a to Gulati Declaration - 12-3-12 USSF Proposed financial Terms 21 Exhibit 16 to Gulati Declaration - Gleason 2005-2011 Revenue 22 Declaration Tom King Declaration 23 Exhibit 1 to King Declaration - Men's CBA 24 Exhibit 2 to King Declaration - Stolzenbach to Levinstein Email 25 Exhibit 3 to King Declaration - 2005 WNT CBA Alex Morgan et al v.