SUPPORTING INFORMATION (SI) Appendix A: Sampling Frame, Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 3 the Missing and Needs of Families

. Addressing the needs of families of the Missing: A test of contemporary approaches to transitional justice Simon Robins PhD Post-war Recovery Studies University of York Post-war Reconstruction and Development Unit (PRDU), Department of Politics June 2011 Abstract This thesis aims to interrogate the current practice of transitional justice from the viewpoint of the victims of the violations that it seeks to address. The study challenges approaches to legacies of violence that are rooted solely in the human rights discourse and that emerge from national and international elites, remote from those most impacted by conflict. The needs of victims of one of the most serious and intractable violations, disappearance, are investigated in two contexts emerging from conflict, Nepal and Timor-Leste, and the impact of ongoing transitional justice process on those needs evaluated. The aim is to understand how a victim-centred transitional justice process can be constructed. Victims of conflict in both Nepal and Timor-Leste have little understanding of rights, articulating the needs, often the most basic, with which they are confronted on a daily basis. Whilst rights are the product of a discourse that claims to be global and universal, needs are necessarily local and particular, the product of culture and context. This drives the methodology of the study which is ethnographic, using qualitative research methods with families of the Missing. The research was conducted in a participatory way with Associations of Families of the Missing, with the aim of empowering victims‟ organisations, and the results published in relevant languages in both contexts with the aim of impacting policy. -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

VBST Short List

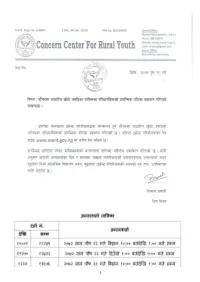

1 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10002 2632 SUMAN BHATTARAI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. KEDAR PRASAD BHATTARAI 136880 10003 28733 KABIN PRAJAPATI BHAKTAPUR BHAKTAPUR N.P. SITA RAM PRAJAPATI 136882 10008 271060/7240/5583 SUDESH MANANDHAR KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. SHREE KRISHNA MANANDHAR 136890 10011 9135 SAMERRR NAKARMI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. BASANTA KUMAR NAKARMI 136943 10014 407/11592 NANI MAYA BASNET DOLAKHA BHIMESWOR N.P. SHREE YAGA BAHADUR BASNET136951 10015 62032/450 USHA ADHIJARI KAVRE PANCHKHAL BHOLA NATH ADHIKARI 136952 10017 411001/71853 MANASH THAPA GULMI TAMGHAS KASHER BAHADUR THAPA 136954 10018 44874 RAJ KUMAR LAMICHHANE PARBAT TILAHAR KRISHNA BAHADUR LAMICHHANE136957 10021 711034/173 KESHAB RAJ BHATTA BAJHANG BANJH JANAK LAL BHATTA 136964 10023 1581 MANDEEP SHRESTHA SIRAHA SIRAHA N.P. KUMAR MAN SHRESTHA 136969 2 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10024 283027/3 SHREE KRISHNA GHARTI LALITPUR GODAWARI DURGA BAHADUR GHARTI 136971 10025 60-01-71-00189 CHANDRA KAMI JUMLA PATARASI JAYA LAL KAMI 136974 10026 151086/205 PRABIN YADAV DHANUSHA MARCHAIJHITAKAIYA JAYA NARAYAN YADAV 136976 10030 1012/81328 SABINA NAGARKOTI KATHMANDU DAANCHHI HARI KRISHNA NAGARKOTI 136984 10032 1039/16713 BIRENDRA PRASAD GUPTABARA KARAIYA SAMBHU SHA KANU 136988 10033 28-01-71-05846 SURESH JOSHI LALITPUR LALITPUR U.M.N.P. RAJU JOSHI 136990 10034 331071/6889 BIJAYA PRASAD YADAV BARA RAUWAHI RAM YAKWAL PRASAD YADAV 136993 10036 071024/932 DIPENDRA BHUJEL DHANKUTA TANKHUWA LOCHAN BAHADUR BHUJEL 136996 10037 28-01-067-01720 SABIN K.C. -

Rolpa-District-Prayer-Guide-Nepali

g]kfn b]zsf] nfuL k|fy{fgf ug{' xf]: ?s'd ;Nofg /f]Nkf Ko"7fg bfª /fKtL, /f]Nkf o]z" v|Li6sf] gfpFdf ;a}nfO{ ho dl;x Û xfd|f] ;'Gb/ b]zsf] x/]s ufpFsf] lglDt k|fy{gf ug{ cfk"mnfO{ xfdL ;Fu} ;lDk{t ug'{ ePsf] nfuL wGojfb lbbF5f}+ . o]z" cfk}mn] x/]s ufpFnfO{ k|]d ug'{ x'GYof] eGg] gd'gf cfkmgf] ;]jfsfO{sf] ;dodf cfkmg} r]nfx?nfO{ Pp6f zx/ b]lv csf]{ ufFpx?df hfFbf b]vfpg' eof] . csf]{ s'/f], o]z" cfkm}n] cfkmgf] r]nfx?nfO{ cfk'mn] u/]em}+ ug{ l;sfpg] / ljleGg ufpFdf k7fpg] sfd ug'{ eof] . afbdf, pxfFn] ;Q/L hgfnfO{ klg b'O{–b'O{ hgf u/L ljleGg ufpFdf k7fpg' eof] . n'sf *–!) cWofo . t/, xfdLx?n] cfh s;/L xfd|f] b]z g]kfnsf] #,(*$ uf=lj=;= sf] lglDt k|fy{gf ug]{< gx]Dofxsf] ;dodf, o?zn]dsf] kv{fn elTsPsf] va/ ox'bfsf bfHo–efO{x?n] NofP . o; kf7df kv{fn zAbn] /Iff, ;'/Iff, cflzif clg Pp6f eljiosf] cfzf b]vfpFb5 . gx]Dofxn] k|fy{gf u/], pkjf; a;], clg dflg;x?sf] kfksf] lglDt kZrtfk klg u/] . k/dk|e'n] gx]Dofxsf] k|fy{gfsf] pQ/ lbg'eof] . w]/} 7"nf] lhDd]jf/L ;f/f kv{fn k'g lgdf0f{ ug'{ kg]{ sfd pxfFsf] cflzif / cg'u|xdf ;Defj eof] . x/]sn] w]/} lj/f]w / ;tfj6 ;fdfgf ug'{ k/]tf klg cfkmgf] c3f8Lsf] kv{fnsf] lgdf0f{ ul//x] . o;/Lg}, xfd|f] nflu x/]s ufpF kv{fnsf] Pp6f O§f h:t} xf] . -

C E N T R a L W E S T E

Bhijer J u m l a Saldang N E P A L - W E S T E R N R E G I O N Patarasi Chhonhup f Zones, Districts and Village Development Committees, April 2015 Tinje Lo M anthang Kaingaon National boundary Zone boundary Village Development Comm ittee boundary Phoksundo Chhosar Region boundary District boundary Gothichour Charang Date Created: 28 Apr 2015 Contact: [email protected] Data sources: WFP, Survey Department of Nepal, SRTM Website: www.wfp.org 0 10 20 40 Rim i Prepared by: HQ, OSEP GIS The designations employed and the presentation of material in M I D - W E Dho S T E R N the map(s) do not imply the expression of any opinion on the Kilom eters part of WFP concerning the legal or constitutional status of any Map Reference: country, territory, city or sea, or concerning the delimitation of its ± frontiers or boundaries. Sarmi NPL_ADMIN_WesternRegion_A0L Pahada © World Food Programme 2015 Narku Chharka Liku Gham i Tripurakot Kalika K A R N A L I FAR-W ESTERN Lhan Raha MID-W ESTERN BJ a Hj a Er kRo It Surkhang Bhagawatitol Juphal D o l p a M u s t a n g W ESTERN Lawan Suhu Chhusang CENTRAL Gotam kot EASTERN Dunai Majhphal Mukot Kagbeni Sahartara Jhong Phu Nar Syalakhadhi Sisne Marpha Muktinath Jom som Tangkim anang Tukuche Ranm am aikot M a n a n g Baphikot Jang Pipal Pwang R u k u m Kowang Khangsar Ghyaru Mudi Pokhara M y a g d i Bhraka Sam agaun Gurja Ransi Hukam Syalpakha Kunjo Thoche W LeteE S T Manang E R N Chokhawang Kanda Narachyang Sankh Shova Chhekam par Kol Bagarchhap Pisang Kuinem angale Marwang Taksera Prok Dana Bihi Lulang Chim khola -

Role of Social Networks in Sampling Hard to Reach Population

Role of Social Networks in Sampling Hard to Reach Population PRAKASH ADHIKARI1 Central Michigan University Abstract: Most research on forced migration acknowledges the fact that acquiring accurate data on refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) is challenging, if not impossible. With the help of a national human rights organization, embedded in communities across Nepal, I employed a weighted multi-stage cluster sampling technique to survey over 1800 individuals from 56 village development committees (VDCs) drawn from 11 of the 75 districts of Nepal to study individual coping behaviors during a decade-long civil war in Nepal. This national sample represents districts that were hard-hit during the conflict, all three topographical regions, all five development regions, and both rural and urban parts of Nepal. Data gathered from the survey are being used in understanding why some individuals flee from their homes while others stay, what are the coping strategies employed by those who chose to stay in their villages, and finally what leads some individuals to return home and others to relocate. Forced migrants typically include two types of individuals, refugees who cross an international border and internally displaced persons (IDPs) who flee their homes but do not cross the border into another country (UNHCR 1951; 1998).2 Scholars in the field acknowledge that it is extremely difficult to obtain accurate data on forced migration caused by conflict (Crisp 1999). This research provides an account of this issue with a description of the problems one faces in enumerating conflict-induced displacement in Nepal. Despite the difficulty in sampling this hard to reach population, I was able to survey over 1800 individuals with the help of social networks such as Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and community level organizations operating at the grassroots level. -

Mcpms Result of Lbs for FY 2065-66

Government of Nepal Ministry of Local Development Secretariat of Local Body Fiscal Commission (LBFC) Minimum Conditions(MCs) and Performance Measurements (PMs) assessment result of all LBs for the FY 2065-66 and its effects in capital grant allocation for the FY 2067-68 1.DDCs Name of DDCs receiving 30 % more formula based capital grant S.N. Name PMs score Rewards to staffs ( Rs,000) 1 Palpa 90 150 2 Dhankuta 85 150 3 Udayapur 81 150 Name of DDCs receiving 25 % more formula based capital grant S.N Name PMs score Rewards to staffs ( Rs,000) 1 Gulmi 79 125 2 Syangja 79 125 3 Kaski 77 125 4 Salyan 76 125 5 Humla 75 125 6 Makwanpur 75 125 7 Baglung 74 125 8 Jhapa 74 125 9 Morang 73 125 10 Taplejung 71 125 11 Jumla 70 125 12 Ramechap 69 125 13 Dolakha 68 125 14 Khotang 68 125 15 Myagdi 68 125 16 Sindhupalchok 68 125 17 Bardia 67 125 18 Kavrepalanchok 67 125 19 Nawalparasi 67 125 20 Pyuthan 67 125 21 Banke 66 125 22 Chitwan 66 125 23 Tanahun 66 125 Name of DDCs receiving 20 % more formula based capital grant S.N Name PMs score Rewards to staffs ( Rs,000) 1 Terhathum 65 100 2 Arghakhanchi 64 100 3 Kailali 64 100 4 Kathmandu 64 100 5 Parbat 64 100 6 Bhaktapur 63 100 7 Dadeldhura 63 100 8 Jajarkot 63 100 9 Panchthar 63 100 10 Parsa 63 100 11 Baitadi 62 100 12 Dailekh 62 100 13 Darchula 62 100 14 Dang 61 100 15 Lalitpur 61 100 16 Surkhet 61 100 17 Gorkha 60 100 18 Illam 60 100 19 Rukum 60 100 20 Bara 58 100 21 Dhading 58 100 22 Doti 57 100 23 Sindhuli 57 100 24 Dolpa 55 100 25 Mugu 54 100 26 Okhaldhunga 53 100 27 Rautahat 53 100 28 Achham 52 100 -

Result on VBST 4Th Round

Reg. S. No. Name Gender Citizenship No. Age District VDC Father Name Mother Name Trainee ID Number 1 11689 AAITI MAYA TAMANG Female 64172 34 Nuwakot Bungtang NURBU TASHI TAMANG SIKUCHA TAMANG 153567 2 15908 AAKANTA SUCHIKAR Male 361039/1102 21 Nawalparasi Parsauni MUKUNDA SUCHIRAR GOMATI SUCHIKAR 154712 3 16153 AAKASH SHRESTHA Male 27-01-72-07907 16 Kathmandu Manmaiju SAMBAK SHRESTHA ASTA MAYA BYANJANKAR 142501 4 14797 AAKASH SHRESTHA Male 24-0-69-00743 22 SindhupalchowkBhotechaur BISHNU SHRESTHA BINA SHRESTHA 144451 Reg. S. No. Name Gender Citizenship No. Age District VDC Father Name Mother Name Trainee ID Number 5 12962 AAKRITI MUKTAN Female 30/01/72/07626 18 KavrepalanchokFoksingtar TIR BAHADUR MUKTAN DHANMAYA MUKTAN 152753 6 13571 AAMME MAYA TAMANG Female 1180/299 36 Rasuwa Dandagoun MANGALE TAMANG SUKUMAYA TAMANG 139662 7 29704 AASHA KAHREL Female 261/29218 24 Dhading Gajuri DHIRENDRA KHAREL NIRMALA KHAREL 143570 8 67530 AASHA MAYA TAMANG Female 3003/36 19 Nuwakot Manakamana NIL BAHADUR TAMANG MAITI TAMANG 154841 9 42357 AASHA RAM TAMANG Male 28-01-71-02278 20 Lalitpur Devichour RAM BDR TAMANG SHUKUMAYA TAMANG 150221 10 21178 AASHIAK BAIDHYA Female 19-02-70-00744 18 Sarlahi Pattharkot SHIVA KUMAR BAIDHYA INDIRA KUMARI BAIDHYA 144659 11 23444 AASHIS LAMA Male 103774 35 KavrepalanchokPokhariNarayansthanKHADGA BAHADUR LAMA MAYA LAMA 142298 12 42684 AASHIS MOTE Male 06-01-71-06634 22 Sunsari MahendranagarGOPAL MOTE SHANTI DEBI MOTE 154078 13 18611 Aashish Bindukar Male 27-01-72-08084 17 Kathmandu Ananda Bindukar Rita Bindukar 142070 14 29465 AASHISH MAHARJAN Male 28-01-72-02824 17 Lalitpur Lalitpur U.M.N.P.AASA RAM MAHARJAN CHIRI MAI MAHARJAN 148724 15 19229 AASHISH PARIYAR Male 28-01-066-01162 24 Lalitpur Lalitpur U.M.N.P.BIKRAM PARIYAR SABITRI PARIYAR 147639 16 42611 AASHISH SHRESTHA Male 273046/40 20 Kathmandu Satungal BISHNU BHAKTA SHRESTHA SAPANA SHRESTHA 154004 17 29443 AASHMAN GOLE Male 52961174 30 Sarlahi Lalbandi BIR BAHADUR GOLE FULMAYA GOLE 146467 18 15669 AASISH KHAKDA Male 439022/256 20 Tanahun SAMSER BD. -

Resource Analysis of Chyuri (Aesandra Butyracea) in Nepal

Micro Enterprise Development Programme - MEDEP GON/MOICS/UNDP – NEP/08/006 Resource Analysis of Chyuri (Aesandra butyracea) in Nepal Micro-Enterprise Development Programme (MEDEP-NEP 08/006) Kathmandu, Nepal June 2010 Copyright © 2010 Micro-Enterprise Development Programme (MEDEP-NEP 08/006) UNDP/Ministry of Industry, Government of Nepal Bakhundole, Lalitpur PO Box 815 Kathmandu, Nepal Tel +975-2-322900 Fax +975-2-322649 Website: www.medep.org.np Author Surendra Raj Joshi Reproduction This publication may not be reproduced in whole or in part in any form without permission from the copyright holder, except for educational or nonprofit purposes, provided an acknowledgment of the source is made and a copy provided to Micro-enterprise Department Programme. Disclaimer The views and opinions expressed in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of MEDEP or the Ministry of Industry. The information contained in this publication has been derived from sources believed to be reliable. However, no representation or warranty is given in respect of its accuracy, completeness or reliability. MEDEP does not accept liability for any consequences/loss due to use of the content of this publication. Note on the use of the terms: Aesandra butyracea is known by various names; Indian butter tree, Nepal butter tree, butter tree. In Nepali soe say Chyuri ad others say Chiuri. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study was carried out within the overall framework of the Micro-Enterprise Development Programme (MEDEP-NEP 08/006) with an objective to identify the geographical and ecological coverage of Chyuri tree, and to estimate the resource potentiality for establishment of enterprises. -

32C73bf0635b6dc07d63e3594d

rfn' cf=j= @)&#÷@)&$ df ljBfno If]q ljsf; sfo{qmd cGtu{t lhNnf lzIff sfof{no dfkm{t ;+rfng x'g] ljBfno ef}lts ;'lawf lj:tf/sf sfo{x? -@ sf]7] gofF sIffsf]7f,$sf]7] ejg ;lxt kmlg{r/ lgdf{0f,zf}rno ;'ljwf ePsf],/ ljBfno ejg dd{t ;+ef/ _ ;+rfngsf nflu lhNnf lzIff WASH sfof{noaf6 5gf]6 eO cfPsf ljBfnox?sf] gfdfjnL ;/f]sf/jfnf ;a}sf] hfgsf/Lsf nflu o; ljefusf] df k|sflzt ul/Psf] 5 . Web Site cf=j= @)&#÷@)&$ df ljBfno ef}lts ;'lawf lj:tf/sf sfo{qmdx? ;+rfngsf nflu lhNnfx?af6 5gf]6 eO cfPsf ljBfnox?sf] gfdfjnL k'jf{~rn != tfKn]h'Ë s= $ sf]7] ejg ;lxt kmlg{r/ lgdf{0f qm=;+= ljBfnosf] gfd 7]ufgf ;"rÍfs s}lkmot lgjf{rg If]q 1 Shree Ambika adharbhut vi. Limbudin 0.83 1 2 Shree Prithavi ma.vi. Khamlung 0.77 2 3 Shree Ganga adharbhut vi. Sanghu 0.63 2 4 Shree Pandolung ma.vi. Nalbu 0.52 2 5 Sherr Jankalyan adharbhut vi. Hangpang 0.51 2 6 Shree Sinwa ucha.ma.vi. Limkhim 0.48 1 7 Shree Durga ucha.ma.vi Sikaicha 0.46 1 8 Shree Kalika ucha.ma.vi. Nangkholyang 0.44 1 9 Shree Sinheswari ma.vi Ankhop 0.42 1 10 Shree Sinam ucha.ma.vi. Sinam 0.4 1 11 Shree Sindhkali adharbhut vi. Thinglabu 0.38 2 12 Shree Sidhkali ucha.ma.vi. Ta.na.Pa 0.35 1 13 Shree Bhanjayang ucha.ma.vi. Limbudin 0.34 1 14 Shree Yangpang adharbhut vi. -

Sampling Hard to Reach Populations: a Survey on Forced Migration During Maoist Insurgency in Nepal Prakash Adhikari*

Articles Sampling Hard to Reach Populations: A Survey on Forced Migration During Maoist Insurgency in Nepal Prakash Adhikari* Tags: nepal, internally displaced persons, forced migration DOI: 10.29115/SP-2013-0013 Survey Practice Vol. 6, Issue 3, 2013 Most research on forced migration acknowledges the fact that acquiring accurate data on refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) is challenging, if not impossible. With the help of a national human rights organization, embedded in communities across Nepal, I employed a weighted multi-stage cluster sampling technique to survey over 1800 individuals from 56 village development committees (VDCs) drawn from 11 of the 75 districts of Nepal to study individual coping behaviors during a decade-long insurgency in Nepal. This national sample represents districts that were hard-hit during the conflict, all three topographical regions, all five development regions, and both rural and urban parts of Nepal. introduction Forced migrants typically include two types of individuals, refugees who cross an international border and internally displaced persons (IDPs) who flee their homes but do not cross the border into another country. Scholars in the field acknowledge that it is extremely difficult to obtain accurate data on forced migration caused by conflict (Crisp 1999). This research provides an account of this issue with a description of the problems one faces in enumerating forced migrants, the role that human rights organizations play in reaching such populations and the sampling method used in the present survey (see Adhikari 2012a for details). the maoist insurgency in nepal and challenges of identifying forced migrants Nepal went through a decade of Maoist insurgency beginning in 1996, in which over 13,000 people were killed, thousands displaced and many more disappeared. -

Kisankalagi Unnat Biu-Bijan Karyakram (KUBK) Improved Seeds for Farmers Programme (ISFP)

Annual Progress Report (Fiscal Year 2016/2017) Loan No.: I-881-NP Supplementary Loan No.: 2000000460 Grant No.: I-DSF-8106-NP Government of Nepal Ministry of Agricultural Development Kisankalagi Unnat Biu-Bijan Karyakram (KUBK) Improved Seeds for Farmers Programme (ISFP) ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT (Fiscal Year 2016/17) Programme Management Office (PMO), Tilottama -3, Janakinagar, Butwal, Rupandehi Phone: 071-420244, Fax: 071-420245 Liaison Office: Manbhawan, Lalitpur Email: [email protected], [email protected] Website: www.kubk.gov.np September 2017 I Kisankalagi Unnat Biu-Bijan Karyakram (KUBK-ISFP) Publication details Publisher Kisankalagi Unnat Biu-bijan Karyakram (KUBK-ISFP) Tilottama -3, Janakinagar, Rupandehi Nepal Publication No: 05-ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT-2016/17-KUBK-ISFP © KUBK-ISFP All right reserved. No Part of this publication reproduced without prior permission of the publisher II Annual Progress Report (Fiscal Year 2016/2017) ACKNOWLEDGMENT It is my great pleasure to present Annual Progress Report of FY 2016/2017. The report has been a joint effort of the project team and it comprehended major progress that achieved by the implementation of the Annual Work Plan and Budget of the reporting period including outputs and outcomes that realized until the four years of its tenure. The Programme has successfully covered 55 percent of targeted households, achieved nearly 61 percent of physical target, and utilized about 37 percent of its allocated total fund including beneficiary’s contribution. Some 496 grant sub-projects were awarded that includes 303 sub-projects for seed production and marketing; and 193 sub-projects for smallholders’ livestock commercialization. The value of the formally marketed 1,526 mt of improve seed is NRs 93.18 million.