Dudley Buck's Grand Sonata in E-Flat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

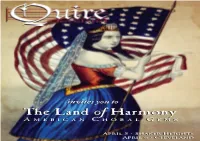

The Land of Harmony a M E R I C a N C H O R a L G E M S

invites you to The Land of Harmony A MERIC A N C HOR A L G EMS April 5 • Shaker Heights April 6 • Cleveland QClevelanduire Ross W. Duffin, Artistic Director The Land of Harmony American Choral Gems from the Bay Psalm Book to Amy Beach April 5, 2014 April 6, 2014 Christ Episcopal Church Historic St. Peter Church shaker heights cleveland 1 Star-spangled banner (1814) John Stafford Smith (1750–1836) arr. R. Duffin 2 Psalm 98 [SOLOISTS: 2, 3, 5] Thomas Ravenscroft (ca.1590–ca.1635) from the Bay Psalm Book, 1640 3 Psalm 23 [1, 4] John Playford (1623–1686) from the Bay Psalm Book, 9th ed. 1698 4 The Lord descended [1, 7] (psalm 18:9-10) (1761) James Lyon (1735–1794) 5 When Jesus wep’t the falling tear (1770) William Billings (1746–1800) 6 The dying Christian’s last farewell (1794) [4] William Billings 7 I am the rose of Sharon (1778) William Billings Solomon 2:1-8,10-11 8 Down steers the bass (1786) Daniel Read (1757–1836) 9 Modern Music (1781) William Billings 10 O look to Golgotha (1843) Lowell Mason (1792–1872) 11 Amazing Grace (1847) [2, 5] arr. William Walker (1809–1875) intermission 12 Flow gently, sweet Afton (1857) J. E. Spilman (1812–1896) arr. J. S. Warren 13 Come where my love lies dreaming (1855) Stephen Foster (1826–1864) 14 Hymn of Peace (1869) O. W. Holmes (1809–1894)/ Matthias Keller (1813–1875) 15 Minuet (1903) Patty Stair (1868–1926) 16 Through the house give glimmering light (1897) Amy Beach (1867–1944) 17 So sweet is she (1916) Patty Stair 18 The Witch (1898) Edward MacDowell (1860–1908) writing as Edgar Thorn 19 Don’t be weary, traveler (1920) [6] R. -

Pipes of the Past: Registration Practices of Selected Composers for the American Centennial Era Organ

PIPES OF THE PAST: REGISTRATION PRACTICES OF SELECTED COMPOSERS FOR THE AMERICAN CENTENNIAL ERA ORGAN By © 2019 Ian K. Classe M.M., Pittsburg State University, 2015 B.A., Truman State University, 2012 Submitted to the graduate degree program in the School of Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Chair: Michael Bauer James Higdon Roberta Freund Schwartz Brad Osborn Susan Earle Date Defended: The dissertation committee for Ian K. Classe certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: PIPES OF THE PAST: REGISTRATION PRACTICES OF SELECTED COMPOSERS FOR THE AMERICAN CENTENNIAL ERA ORGAN Chair: Michael Bauer Date Approved: ii Abstract American organ music prior to the twentieth century is a somewhat neglected area of organ study due to biases of early-twentieth-century academia. This lecture seeks to better familiarize the audience with a small section of that neglected study by examining the relationship between the organs, composers, and compositions of the Centennial era (ca. 1870–1900) through the lens of organ registration. This particular period of nineteenth-century American music became the era when American composers developed a quintessentially American culture around the organ—a culture which would provide the foundation for much of what came after it. By examining this period and its contributions, we gain a better understanding of later musical developments in the organ world and an appreciation for what came before. iii Acknowledgements I would like to offer special thanks to Dr. Rosi Kaufman, Director of Music at Rainbow Mennonite Church, for her knowledge and assistance on this project as well as facilitating my use of the Hook organ for the lecture recital. -

THE MUSICAL CRITIC and TRADE REVIEW. 3T>5

Music Trade Review -- © mbsi.org, arcade-museum.com -- digitized with support from namm.org May 5th, 1882. THE MUSICAL CRITIC AND TRADE REVIEW. 3t>5 HISS AMELIA WDKM1!. first musical utterances were from "The Lock festivals twenty-four years ago. The quarter cen- Miss Amelia Wurmb, mezzo soprano, came Hospital" and other collections of hymn tunes tennial festival of the association will occur dur- here last fall with an excellent reputation as then in general use in New England. By degrees ing the last week in September. Among other concert singer in Paris, Vienna, Berlin, Kome, music of a higher order was rehearsed. works the society has in preparation for this event and other European musical centres. Miss Wurmb Its first public performance was given on Christ- the "Damnation of Faust," by Berlioz; Scenes was born in Vienna in 1853. When eight years of mas Day, 1815, at Stone Chapel, now called King's from "Lohengrin," by Wagner; the Ninth Sym- age she played the organ on several occasions in Chapel, to an audience of one thousand persons. phony, and "The Messiah." For fifteen years Mr. the cathedral in which her sister was the soprano. The chorus consisted of about one hundred, of Carl Zerrahn has been not only the conductor at • At one time when her sister was ill she sang the whom ten were ladies, while an orchestra of about the annual festivals of the association, but the solos in a mass in her stead, being at the time a dozen instruments and the organ furnished the chorus master, all rehearsals being held under his scarcely nine years of age. -

Romantic American Choral Music David P. Devenney, Presenter

The Sea Hath Its Pearls: Romantic American Choral Music 2021 National Conference, American Choral Directors Association March 19, 2021, 11:30 a.m. David P. DeVenney, presenter West Chester University of Pennsylvania The Sea Hath its Pearls (JCD Parker, Seven Part Songs) Introduction Elements of Style: Melody and Harmony Kyrie (Bristow) Vittoria Rybak, mezzo soprano Parvum quando cerno Deum (Chadwick) [When we see our tiny Lord This beautiful mother, held in his mother’s arms, This mother with her beautiful son, it salves us in our breasts such a lovely one all pink, with a thousand joys. like a violet that became a lily. The eager boy, eagerly seeing, [O that one of the arrows, your mother above all: sweet or boyish, while the smiling boy which should pierce the mother’s breast, is kissed a thousand times.] may fall upon me, little Jesus!] *Such a simple brightness -Author Unknown shines through the child, (* text for excerpted portion) The mother clings to him. Requiem aeternum (Buck) Elements of Style: Structure and Craft The Lord of Hosts Is with Us (Gilchrist) Sing Hallelujah (H. Parker) And They Shall Reign (JCD Parker) Music for Women’s and Men’s Voices Sanctus (Hadley) Emily Salatti, soprano At Sea (Buck) Concluding Remarks Seven Part Songs (JCD Parker) The World’s Wanderers The West Wind The Composers in this Presentation George Frederick Bristow (1825-1898) spent the majority of his life in New York City. By age 11 he was playing the violin at the Olympic Theatre in New York and later spent over thirty years playing violin with the New York Philharmonic Society. -

CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Founded by THEODORE THOMAS in 1891

CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Founded by THEODORE THOMAS in 1891 FREDERICK STOCK Conductor THE THURSDAY-FRIDAY SERIES Concerts Nos. 2553 and 2554 IIIIIIIIIIIIIUIIIIIIIIII FORTY-NINTH SEASON TWENTY-SEVENTH PROGRAM APRIL 11 AND 12, 1940 iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiinn ORCHESTRA HALL Air-Conditioned for Winter and Summer Comfort CHICAGO Slljr ©rrbi’strd Assonatimi 1939 — FORTY-NINTH SEASON—1940 ORGANIZATION The Orchestral Association consists of forty members, from whom fifteen are elected as Trustees. The officers of the Association are elected from the Trustees, and these Officers, with three other Trustees and the Honorary Trustees, compose the Executive Committee. OFFICERS CHARLES H. HAMILL, Honorary President EDWARD L. RYERSON, Jr., President ALBERT A. SPRAGUE, Vice-President CHARLES H. SWIFT, Second Vice-President ARTHUR G. CABLE, Third Vice-President CHALKLEY J. HAMBLETON, Secretary FRANCIS M. KNIGHT, Treasurer HONORARY TRUSTEES and Ex-Officio Members of Executive Committee Joseph Adams Charles H. Hamill Russell Tyson OTHER MEMBERS OF EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Charles B. Goodspeed Ralph H. Norton John P. Welling OTHER TRUSTEES Cyrus H. Adams Alfred T. Carton Harold F. McCormick Daniel H. Burnham Arthur B. Hall J. Sanford Otis OTHER MEMBERS OF THE ASSOCIATION Richard Bentley William B. Hale Theodore W. Robinson Bruce Borland George Roberts Jones Charles Ward Seabury John Alden Carpenter Frank O. Lowden Emanuel F. Selz Mrs. Clyde M. Carr Chauncey McCormick Durand Smith William B. Cudahy Leeds Mitchell Robert J. Thorne Edison Dick Charles H. Morse Mrs. Frederic W. Upham Albert D. Farwell Mrs.BartholomayOsborneErnest B. Zeisler Walter P. Paepcke OFFICES: SIXTH FLOOR, ORCHESTRA BUILDING 220 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago HENRI E. VOEGELI, Assistant Treasurer and Business Manager CHARLES F. -

AGO NOVEMBER 2010 NL.Pub

The Organizer November 2010 A G O Monthly Newsletter The Atlanta Chapter L O G O AMERICAN GUILD The of ORGANISTS Organizer November 2010 ATLANTA C HAPTER AGO Atlanta PRESENTS Chapter Officers CHERRY RHODES Dean CONCERT O RGANIST Jeff Harbin at Sub-Dean Tim Young IMMACULATE H EART OF M ARY C HURCH 2855 Briarcliff Road NE Secretary Atlanta, Georgia 30329 Betty Williford 404.636.1418 Treasurer Host: William Jefferson Bush and the Charlene Ponder A. E. Schlueter Pipe Organ Company Registrar Tom Wigley TUESDAY , N OVEMBER 9 Newsletter/Yearbook Editor Punchbowl: 6:00 pm Charles Redmon Dinner & Meeting: 6:30 pm Recital: 8:00 pm Chaplain _________________________________________________________________________ Rev. Dr. John Beyers The cost for meals this season will be $14 DEADLINE FOR RESERVATIONS WILL BE T HURSDAY , N OVEMBER 4 Auditor [email protected] David Ritter Webmaster Cherry Rhodes is the first American to win an international organ Steven Lawson competition (Munich, Germany). She has played recitals at Notre Dame Executive Cathedral in Paris, at international organ festivals throughout Europe Committee and at numerous National and Regional Conventions of the American Jeff Daniel ‘11 Guild of Organists. In July 2004 she was one of the first organists to Jeremy Rush ‘11 Madonna Brownlee ‘12 perform on the new organ in the Walt Disney Concert Hall. This John Sabine ‘12 occasion took place at the AGO National Convention when she appeared as soloist with Randy Elkins ‘13 members of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Subsequently she performed there for the John Gentry ‘13 Grand Avenue Festival, and continuing with the organ inauguration, on April 22-24, 2005, she performed the monumental Symphonie Concertante by Joseph Jongen on the Los Angeles Philharmonic Subscription Series. -

Volume 11, Number 07 (July 1893) Theodore Presser

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 7-1-1893 Volume 11, Number 07 (July 1893) Theodore Presser Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Presser, Theodore. "Volume 11, Number 07 (July 1893)." , (1893). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/373 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WM. A. POND * CO., 25 Union Square, New York, MUSIC PUBLISHERS AND IMPORlEfiS. STANDARD BOOKS. Pianoforte Teachers’ Certificates. Examiners: William Mason, Mos. I>oc., A. C. M., and Mann’s New Piano Method,.$2.50 Albert Ross Parsons, A. C. M. Embodies all the latest improvements in teaching, The R. Huntington Woodman Organ Scholarship is is written expressly for the nse of beginners, is com¬ to be Competed for June 15th at the College. prehensive, systematic, and progressive, secures to the student the best position of the hand, correct This College has no equal for thoroughness of instruc¬ tion and the absolute satety of the methods. and rapid execution, ability to read music at sight, The Voice Department, headed by H. -

The Musical Journey

Becoming AmericAn The Musical Journey A concert presented by The Historic new orleans collection & Louisiana Philharmonic orchestra “Becoming American: The Musical Journey” is the sixth installment of musical Louisiana: America’s cultural Heritage, an annual series presented by The Historic new orleans collection and the Louisiana Philharmonic orchestra. Dedicated to the study of Louisiana’s contributions to the world of classical music, the award-winning program also provides educational materials to more than two thousand fourth- and eighth-grade teachers in Louisiana’s public and private schools. Since the program’s inception, musical Louisiana has garnered both local and national recognition. The 2008 presentation, “music of the mississippi,” won the Big easy Award for Arts education; “made in Louisiana” (2009) received an Access to Artistic excellence grant from the national endowment for the Arts; and “identity, History, Legacy: La Société Philharmonique” (2011) received an American masterpieces: Three centuries of Artistic genius grant from the national endowment for the Arts. “Becoming American: The musical Journey” celebrates the bicentennial of Louisiana’s statehood and complements the exhibition The 18th Star: Treasures from 200 Years of Louisiana Statehood, on view through January 29, 2012, at The Historic new orleans collection, 533 royal Street. The collection further observes the bicentennial with the seventeenth annual Williams research center Symposium, Louisiana at 200: In the National Eye, taking place Saturday, January 28, 2012. more information about these events is available at www.hnoc.org or by calling (504) 523-4662. Live internet streaming of this concert on www.LPomusic.org is supported by the Andrew W. -

THE FOUNDERS of the AGO—WHO WERE THEY? Barbara Owen, Chm

AMERICAN GUILD OF ORGANISTS CENTENNIAL THE FOUNDERS OF THE AGO—WHO WERE THEY? Barbara Owen, ChM Their names crop up on old anthems that have not been sung for years, and sprightly organ variations played at Organ Historical Society conventions. Go back far enough in old issues of The Diapason or the “original” The American Organist and their stiffly :‘ posed likenesses peer back at you from the V yellowed pages. An occasional plaque in some metropolitan church serves as a re ‘I minder that their fingers once touched the keys of an organ there. - Many of them were giants in their day, - . .• men (they were mostly men) to be reckoned ,:_ ‘ with at an organ console or on a podium. A surprising number are mentioned in the 1935 Grove’s Dictionary or its American Supplement, as well as in other standard sources. Most of them were from the eastern cities, but places as far away as Colorado and California are represented, and one Founder was a Canadian. Most had good Anglo-Sax- on surnames, but there is also a smattering of names betraying German, French, Scandina d’Indy FRANKLIN BASSETT. b. 1852 Wheeling, W.Va.; vian, and Italian origins. And of the 145 that 0: Churches in Meadville, Pa., and Toledo, Ohio, d. 1915 were designated as “Founders” on the final 1879—86 5: Reinecke in Leipzig day of 1896, a tiny minority—four, in fact— First Congregational Church, Oberlin, Ohio 0: First Methodist Church, Plymouth Church, St. were women. Two Founders died durirtg the Second Congregational Church, Oberlin, Ohio Paul’s Church, Cleveland, Ohio year following the founding of the Guild, but T: Oberlin Conservatory 1886; Prof. -

February 1944) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 2-1-1944 Volume 62, Number 02 (February 1944) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 62, Number 02 (February 1944)." , (1944). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/220 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. February THE ETUDE 1944 Price 25 Cents music maaaiine THE ORATORIO SOCIETY OF NEW YORK, so ably conducted for twenty-two years by the late Albert Stoessel, gave in December its one hundred twentieth CoLLe^ge performance of Handel’s “Messiah.” The most UnusuAL presentation was directed by Alfred M. ^AmemcA's years the assistant Greenfield, for fifteen conductor of the Society. R. HUNTINGTON WOODMAN, distin- guished organist and composer, who before his retirement in 1941 had been for sixty-one years 94 9nteteMl in the- 9n(!lUti&u<*l £tu<6&nt organist and choirmas- ter of the First Presby- HERE. THERE, AND EVERYWHERE EDUCATIONAL terian Church, Brooklyn, FINE VIOLINS ARE NOT TURNED OUT IN MASS PRODUCTION. Dr. R. Hunting- died in that city on De- IN THE MUSICAL WORLD ton Woodman cember 25, aged eighty- Festival Over- eighty-eight, in congratulating her upon REGIMENTATION DOES NOT DEVELOP LEADERS. -

The History of the Pipe Organ at First Presbyterian Church Austin, Texas

The History of the Pipe Organ at First Presbyterian Church Austin, Texas Compiled by Scott McNulty, SP, CAGO Music has been an important part of First Presbyterian Church from the very beginning. Founded in 1850 in the Texas State Capitol log cabin, some historians date the church back earlier to 1839. Possibly made in Concord, Massachusetts, the original instrument at First Church was a harmonium that lasted until about 1857. A five octave melodia was then purchased for $300 from George A. Prince of Buffalo, New York. One picture of the church in 1897 shows an organ with several ranks of pipes, both wood and metal, in the chancel area of the church and could be the melodia organ. Under the leadership of long-time pastor, the Reverend E. B. Wright, the 1890 church building was built debt free. When the opportunity came later to add a fine pipe organ, the church was able to do so without adding to any existing mortgage debts. In October of 1899, the purchase of a pipe organ was approved by the Session at a cost of $2500. As part of the agreement, the old melodia organ was sold for $300 to the organ builder, the Möller Organ Company of Hagerstown, Maryland. Mathias Peter Möller was born in Denmark in 1854 and began working as an apprentice with a carriage maker before coming to the United States at age seventeen. Later known for building luxury cars and taxicabs, Möller used his mechanical skills to good use in the organ industry. A series of moves in Pennsylvania and a disastrous fire at the Hagerstown location in 1895 allowed the company to rebuild and expand from a production of 20 organs a year to over 250 organs a year by 1921. -

Dudley Buck and Inspired the Parody on Page 23

OHS American Organ Archive at Talbott Library, Westminster Choir College, Princeton, New Jersey Members may join any number of chapters. Chapters, Newsletter, Editor, Membership Founding Date & Annual Dues Inquiries Boston Organ Club Newsletter, $7.50 Aliln L.1ufman 1965, '76 OHS Charter Box 104 Harrisville, NH 03450 Central New York, The Coupler, Phil Williams 1976 Box F Cullie Mowers, $5 Remsen, NY 13438 Chicago Midwest, The Stopt Diapason, Julie Stephens 10 South Catherine 1980 Susan R. Friesen, $12 La Grange, IL 60525 The Organ Historical Society Eastern Iowa, 1982 Newsletter, August Knoll Box486 Dennis Ungs, $7.50 Post Office Box 26811 Wheolland,IA 52777 Greflter New York The Keraulophon, Alan Laufman Richmond, Virginia 23261 Box 104 City, 1969 John Ogasapian, $5 (804)353-9226 FAX (804)353-9266 Harrisville, NH 03450 Greater Sr. Louis, The Cypher, Elizabeth John D.Phillippe 1975 4038 Sonorn Ct, The National Council Schmitt, $5 Columbia, MO 65201 TERM Officers and Councillors EXPIRES Harmony Society Clariana, The Rev. Leo Walt Adkins (Western PA & Ohio Longan,$5 476 FirstS1. Kristin Farmer President (1995) Heidelberg, PA 15106 3060 FraternityChurch Rd,, Winston-Solem, NC 27107 Valley), 1990 Thomas R. Rench ...........................Vice-President (1997) Hilbus (Washington Where the Tracker Ruth Charters Bnltimore), 1970 Action Is, Carolyn 6617 BrnwnerSt . 1601 Circlewood Dr., Racine, Wl 53402 McLean,VA 22102 Richard J.Ouellette ............................ Secretary (1995) Fix, $5 21 Mechanic Street, West Newbury, MA 01985-1512 Kentuckiam1 Quarter Notes, $10 Keith E.Norrington (Kentucky-S.Indiana), 629 Roseview Terrace David M.Barnett .......................... Treasurer (appointed) New Albany, IN 47150 423 N. StaffordAve. , Richmond, VA 23220 1990 Jonathan Ambrosino .....Councillor for Research & Publications (1995) Memphis, 1992 TBA, $5 Dennis S.