Through the Looking Glass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collaborative Approaches to Archaeological Site Preservation

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2013 Hearts and Minds: Collaborative Approaches to Archaeological Site Preservation Mark Russell Sanders University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Sanders, Mark Russell, "Hearts and Minds: Collaborative Approaches to Archaeological Site Preservation" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 572. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/572 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. HEARTS AND MINDS: COLLABORATIVE APPROACHES TO ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE PRESERVATION ______________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver ______________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ______________ By Mark Russell Sanders June 2013 Advisor: Bonnie Clark i Author: Mark Russell Sanders Title: HEARTS & MINDS: COLLABORATIVE APPROACHES TO ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE PRESERVATION Advisor: Dr. Bonnie Clark Degree Date: June 2012 Abstract Archaeological relic hunting on public lands in the southwestern United States accelerated with 19th century westward expansion and it continues today. Efforts to curb looting through the passage and enforcement of laws has been only moderately successful. Americans’ misunderstandings of archaeology’s ethical responsibilities, particularly with regard to Native Americans and other descendant communities, have further undermined historic preservation initiatives. My thesis addresses the usefulness of public, private, and nonprofit site protection efforts in changing the beliefs and behaviors associated with site looting, focusing particularly on the need for collaboration outside the heritage management profession. -

Pueblo III Towers in the Northern San Juan. Kiva 75(3)

CONNECTING WORLDS: PUEBLO III TOWERS IN THE NORTHERN SAN JUAN Ruth M. Van Dyke and Anthony G. King ABSTRACT The towers of the northern San Juan, including those on Mesa Verde, Hovenweep, and Canyons of the Ancients National Monument, were constructed on mesa tops, in cliff dwellings, along canyon rims, and in canyon bottoms during the Pueblo III period (A.D. 1150–1300)—a time of social and environmental upheaval. Archaeologists have interpreted the towers as defensive strongholds, lookouts, sig- naling stations, astronomical observatories, storehouses, and ceremonial facilities. Explanations that relate to towers’ visibility are most convincing. As highly visible, public buildings, towers had abstract, symbolic meanings as well as concrete, func- tional uses. We ask not just, “What were towers for?” but “What did towers mean?” One possibility is that towers were meant to encourage social cohesiveness by invoking an imagined, shared Chacoan past. The towers reference some of the same ideas found in Chacoan monumental buildings, including McElmo-style masonry, the concept of verticality, and intervisibility with iconic landforms. Another possibility is that towers symbolized a conduit out of the social and envi- ronmental turmoil of the Pueblo III period and into a higher level of the layered universe. We base this interpretation on two lines of evidence. Pueblo oral tradi- tions provide precedent for climbing upwards to higher layers of the world to escape hard times. Towers are always associated with kivas, water, subterranean concavities, or earlier sites—all places that, in Pueblo cosmologies, open to the world below our current plane. RESUMEN Las torres del norte del San Juan, inclusive ésos en Mesa Verde, en Hovenweep, y en el monumento nacional de Canyons of the Ancients, fueron construidos en cimas de mesa, en casas en acantilado, por los bordes de cañones, y en fondos de cañones durante Pueblo III (dC. -

Ancestral Pueblo Indians of Southwestern Colorado

Ancestral Pueblo Indians of Southwestern Colorado Who were the Ancestral Pueblo Indians of southwestern Colorado? What happened to them? Why is it important to preserve the sites they left behind? By Kristin A. Kuckelman* Standards Addressed and Teaching Strategies by: Corey Carlson, Zach Crandall, and Marcus Lee** * Kristin A. Kuckelman has been a professional archaeologist for more than 35 years and has conducted excavations at many ancestral Pueblo sites. Her research results have been published in professional journals such as American Antiquity, Kiva, Archaeology, American Scientist, and Archaeology Southwest, in many edited volumes on warfare, bioarchaeology, and the archaeology of the northern Southwest, and have been featured on BBC television programs and National Public Radio. She served as president of the Colorado Council of Professional Archaeologists and is currently a researcher and the research publications manager at the Crow Canyon Archaeological Center near Cortez, Colorado. Kristin can be reached at [email protected]. ** Corey Carlson teaches 4th grade at Foothills Elementary in Boulder, Zach Crandall teaches 8th grade U.S. Society at Southern Hills Middle School in Boulder, and Marcus Lee teaches and is the chair of the social studies department at George Washington High School in Denver. 1 Contents Standards Addressed Background Primary Sources Ancestral Puebloans 1. Map of the Mesa Verde Region 2. Basketmaker Lifeways 3. Basketmaker Pottery 4. Pueblo I Lifeways 5. Red Ware Pottery 6. Pueblo II Lifeways 7. Pueblo II Pottery 8. Pueblo III Lifeways 9. Pueblo III Pottery Mesa Verde National Park 10. Cliff Palace, Late 1800s 11. Gustaf Nordenskiöld and the American Antiquities Act 12. -

Cultural Implications of Architectural Mortar and Plaster Selection at Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2007 Cultural implications of architectural mortar and plaster selection at Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado Shane David Rumsey University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Rumsey, Shane David, "Cultural implications of architectural mortar and plaster selection at Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado" (2007). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 2261. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/5fyg-wtzn This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CULTURAL IMPLICATIONS OF ARCHITECTURAL MORTAR AND PLASTER SELECTION AT MESA VERDE NATIONAL PARK, COLORADO By Shane David Rumsey Bachelor of Science Weber State University 2002 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Anthropology Department of Anthropology College of Liberal Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1452273 Copyright 2008 by Rumsey, Shane David All rights reserved. -

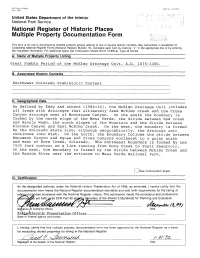

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form R Fi'-'-^--'':-'-I^T--K~

NFS Form 10-900-b (Jan 1987) United States Department of the Interior \ ! ! ; National Park Service \ ~ [ *•} National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form r fi'-'-^--'':-'-i^T--K~ This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines lor Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing_________________________________________ Great Pueblo Period of the McElmo Drainage Unit/ A.D. 1075-1300. B. Associated Historic Contexts_____________________________________________ Southwest Colorado Prehistoric Context C. Geographical Data___________________________________________________ As defined by Eddy and others (1984:34), the McElmo Drainage Unit includes all lands with drainages that ultimately feed McElmo Creek and the Cross Canyon drainage east of Montezuma Canyon. On the south the boundary is formed by the north slope of the Mesa Verde, the divide between Mud Creek and Navajo Wash, the north slopes of Ute Mountain and the divide between Rincone Canyon and East McElmo Creek. On the west, the boundary is formed by the Colorado State Line, although geographically, the drainage unit continues into Utah. On the north, the boundary follows the divide between Monument Canyon and Squaw and Cross Canyons northeast to a point north and east of Dove Creek, Colorado. The northeast boundary is formed by the 7000 foot contour on a line running from Dove Creek to Puett Reservoir. On the east, the boundary is formed by the divide between McElmo Creek and the Mancos River near the entrance to Mesa Verde National Park. -

Early Pueblo Responses to Climate Variability: Farming Traditions, Land Tenure, and Social Power in the Eastern Mesa Verde Region

EARLY PUEBLO RESPONSES TO CLIMATE VARIABILITY: FARMING TRADITIONS, LAND TENURE, AND SOCIAL POWER IN THE EASTERN MESA VERDE REGION Benjamin A. Bellorado and Kirk C. Anderson Abstract Maize agriculture is dependent on two primary environmental factors, precipi- tation and temperature. Throughout the Eastern Mesa Verde region, fluctuations of these factors dramatically influenced demographic shifts, land use patterns, and social and religious transformations of farming populations during several key points in prehistory. While many studies have looked at the influence climate played in the depopulation of the northern Southwest after A.D. 1000, the role that climate played in the late Basketmaker III through the Pueblo I period remains unclear. This article demonstrates how fluctuations in precipitation pat- terns interlaced with micro- and macro- regional temperature fluctuations may have pushed and pulled human settlement and subsistence patterns across the region. Specifically, we infer that preferences for certain types of farmlands dic- tated whether a community used alluvial fan verses dryland farming practices, with the variable success of each type determined by shifting climate patterns. We further investigate how dramatic responses to environmental stress, such as migration and massacres, may be the result of inherited social structures of land tenure and leadership, and that such responses persist in the Eastern Mesa Verde area throughout the Pueblo I period. Resumen La agricultura de maíz depende de dos factores ambientales primarios: precipitación y temperatura. A lo largo de la región oriental de Mesa Verde las fluctuaciones de estos fac- tores influyeron dramáticamente en cambios demográficos, patrones de uso de la tierra así como transformaciones sociales y religiosas en las poblaciones agrícolas durante varios momentos clave en la prehistoria. -

Historic Buildings Survey Phase IV North Side of Main Street Cortez, Colorado 2016

Historic Buildings Survey Phase IV North Side of Main Street Cortez, Colorado 2016 CLG grant number CO-15-016 Prepared by Cultural Resource Planning Jill Seyfarth PO Box 295 Durango, Colorado 81302 Historic Buildings Survey Phase IV North Side of Main Street Cortez, Colorado 2016 Prepared for the Cortez Historic Preservation Board The City of Cortez 210 East Main Cortez, Colorado 81321 Historic Preservation Board Chairman-Linda Towle Dale Davidson Joyce Lawrence Dan Giannone Terry McCabe Mitchell Toms Janet Weeth Cortez City Staff Chris Burkett Neva Connolly Doug Roth Prepared by: Jill Seyfarth Cultural Resource Planning PO Box 295 Durango, Colorado 81302 (970) 247-5893 May, 2016 CLG grant number CO-15-016 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1 Background/Purposes Federal Funding Acknowledgement Project Description Survey Area................................................................................................................... 3 Legal Description Physical Setting Research Design and Methods .................................................................................... 7 Survey Methodology Historic Contexts ......................................................................................................... 11 Survey Results ............................................................................................................. 27 Developmental History of the Survey Area Construction Dates and Architectural -

Pueblo Grande Museum ‐ Partial Library Catalog

Pueblo Grande Museum ‐ Partial Library Catalog ‐ Sorted by Title Book Title Author Additional Author Publisher Date 100 Questions, 500 Nations: A Reporter's Guide to Native America Thames, ed., Rick Native American Journalists Association 1998 11,000 Years on the Tonto National Forest: Prehistory and History in Wood, J. Scott McAllister, et al., Marin E. Southwest Natural and Cultural Heritage 1989 Central Arizona Association 1500 Years of Irrigation History Halseth, Odd S prepared for the National Reclamation 1947 Association 1936‐1937 CCC Excavations of the Pueblo Grande Platform Mound Downum, Christian E. 1991 1970 Summer Excavation at Pueblo Grande, Phoenix, Arizona Lintz, Christopher R. Simonis, Donald E. 1970 1971 Summer Excavation at Pueblo Grande, Phoenix, Arizona Fliss, Brian H. Zeligs, Betsy R. 1971 1972 Excavations at Pueblo Grande AZ U:9:1 (PGM) Burton, Robert J. Shrock, et. al., Marie 1972 1974 Cultural Resource Management Conference: Federal Center, Denver, Lipe, William D. Lindsay, Alexander J. Northern Arizona Society of Science and Art, 1974 Colorado Inc. 1974 Excavation of Tijeras Pueblo, Tijeras Pueblo, Cibola National Forest, Cordell, Linda S. U. S.DA Forest Service 1975 New Mexico 1991 NAI Workshop Proceedings Koopmann, Richard W. Caldwell, Doug National Association for Interpretation 1991 2000 Years of Settlement in the Tonto Basin: Overview and Synthesis of Clark, Jeffery J. Vint, James M. Center for Desert Archaeology 2004 the Tonto Creek Archaeological Project 2004 Agave Roast Pueblo Grande Museum Pueblo Grande Museum 2004 3,000 Years of Prehistory at the Red Beach Site CA‐SDI‐811 Marine Corps Rasmussen, Karen Science Applications International 1998 Base, Camp Pendleton, California Corporation 60 Years of Southwestern Archaeology: A History of the Pecos Conference Woodbury, Richard B. -

Chapter 9 PUEBLO III (A.D. 1150-1300)

Chapter 9 PUEBLO III (A.D. 1150-1300) William D. Lipe and Mark D. Varien INTRODUCTION As described in Chapter 3, the well-preserved cliff dwellings and large open sites of the Pueblo III period first drew wide public attention to the archaeology of southwestern Colorado in the late nineteenth century, and these site types have played a large role in archaeological research in the area ever since. The cliff dwellings and canyon-rim towers of the study area have also come to represent Southwestern archaeology to a significant segment of the American and international public. Hundreds of thousands of people visit Mesa Verde National Park annually, and striking images of Pueblo III architecture are presented to many thousands more in videos, books, articles, lectures, and classes. Generations of archaeologists, including some of the more prominent figures in the field, have labored to understand the archaeological record of this period in the study area, and to construct accounts of how these Pueblo people lived and why they left the area late in the thirteenth century. Pueblo III research has both reflected and influenced the emphases and interpretations characteristic of various periods in the history of the area's archaeology (see Chapter 3). Although Pueblo III research has continued through each of these periods, it has been a larger component in some than in others. Certainly Pueblo III sites were the predominant focus of what was recognized in Chapter 3 as the "period of initial exploration and reconnaissance (1776-1912)." Between about I 912 and 1957, Southwestern archaeologists focused on developing regional chronological sequences and filling gaps in archaeological coverage of at least the Formative stage ofthe record. -

Mesa Verde National Park

MESA VERDE NATIONAL PARK • COLORADO + UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR RATIONAL PARK SERVICE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR HAROLD L. IOKES, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE ARNO B. CAMMERER, Director MESA VERDE NATIONAL PARK COLORADO SEASON FROM MAY 15 TO OCTOBER 15 UNITED STATES. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1935 RULES AND REGULATIONS IMPORTANT EVENTS IN MESA VERDE'S Automobiles.—Drive carefully; free-wheeling is prohibited within the PREHISTORY AND HISTORY park. Obey park traffic rules and speed limits. Secure automobile permit, IOOO B. C. Occupancy of the Cliff Palace cave by first agricultural Indians of the South fee Si-oo per car. west. Date represents archeologist's approximation of the earliest known use of Fires.—Confine fires to designated places. Extinguish completely before the caves of Mesa Verde by man. leaving camp, even for temporary absences. Do not guess your fire is out— 500 B. C. Estimated date of the second agricultural people. Their habitations extended KNOW IT. over the entire Mesa Verde and their culture excelled in the introduction and Firewood.—Use only the wood that is stacked and marked "firewood" perfection of many arts. 1066 A. D. Earliest date established for cliff-dweller culture. Beam section from Jug House. near your campsite. By all means do not use your axe on any standing tree 1073. Construction of Cliff Palace. or strip bark from the junipers. 1776. Expedition of Padre Silvestre Velez de Escalante to southwestern Colorado. Party Grounds.—Burn all combustible rubbish before leaving your camp. Do camped at the base of the Mesa Verde. not throw papers, cans, or other refuse on the ground or over the canyon 1859. -

Small Ancestral Pueblo Sites in the Mesa Verde

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts SMALL ANCESTRAL PUEBLO SITES IN THE MESA VERDE REGION: LOCATION, LOCATION, LOCATION A Dissertation in Anthropology by A’ndrea Elyse Messer ©2009 A’ndrea Elyse Messer Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2009 This dissertation of A’ndrea Elyse Messer was reviewed and approved* by the following: George Milner Professor of Anthropology Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee David Webster Professor of Anthropology Dean Snow Professor of Anthropology Christopher Duffy Professor of Civil Engineering Nina Jablonski Professor and Head, Department of Anthropology *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT A basic theoretical issue in settlement archaeology is the effect that environment on the one hand, or large centers on the other, have on the placement of small habitations. A key methodological issue is whether old survey data, collected at a time when today’s questions had not yet been formed, can still prove useful. This dissertation investigates the viability of old survey data, some of the environmental influences – landform, elevation, temperature, precipitation – and settlement population density, on site location choice in the Mesa Verde Southwest. I also investigated the effects of large sites on small site location and looked at all these factors with respect to reinhabited sites versus pristine sites. My results suggest a method to determine which old surveys can be used, and which cannot. The site populations in the mesa surveys are similar but differ from the site populations of the non-mesa surveys, indicating a possible difference in settlement pattern between mesas and other areas. -

The Moki Messenger

THE MOKI MESSENGER SEPTEMBER 2017 SAN JUAN BASIN ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY www.sjbas.org Next SJBAS Meeting– Wednesday, September 13th The next SJBAS meeting will be held on Wednesday, September 13th, at 7:00 p.m. in the Lyceum at the Center Table of Contents of Southwest Studies at Fort Lewis College. After a brief business meeting, Dr. Jesse Tune, FLC Professor, will Page 1 Next SJBAS meeting info present: “The Times They Were ‘A-Changin’: Life on the Page 1 Letter from the President Colorado Plateau at the End of the Ice Age.” A social will Page 2 John W. Sanders Lecture Series be held before the meeting at 6:30 p.m. in the CSWS Page 3 SJBAS August meeting notes foyer. Page 4 SJBAS September volunteer needs Page 4 SJBAS August Board Mtg. Highlights Tune’s talk will present a picture of what life was like on Page 5 PAAC class in Durango the northern Colorado Plateau at the end of the last Ice Page 6 SJBAS Field Trip and Activity Schedule Age. He will focus on the archaeological record, as well as Page 6 CAS News the paleoenvironmental record of the region around Page 6 CAS Annual Meeting registration info 13,000 years ago. He will specifically address the Page 7 CAS Chapter News archaeological record of Bears Ears National Monument. Page 7 Regional Archaeology News Page 8 SJBAS officers and contact info Dr. Tune is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Anthropology at Fort Lewis College. He specializes in Paleoindian archaeology, lithic analysis, and human/environment relationships.