Project Synopsis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maternal-Newborn Gap Analysis a Review of Low Volume, Rural, and Remote Intrapartum Services in Ontario

The Provincial Council for Maternal and Child Health Maternal-Newborn Gap Analysis A review of low volume, rural, and remote intrapartum services in Ontario. August, 2018 Project Team Vicki Van Wagner, RM, PhD Associate Professor, Ryerson University Jane Wilkinson, BSc., MD, FRCSC, CSPE Obstetrician-Gynecologist Doreen Day, MHSc Senior Program Manager, Provincial Council for Maternal and Child Health Laura Zahreddine, RN, BScN, MN Program Coordinator, Provincial Council for Maternal and Child Health Sherry Chen, MBBS, MHI Decision Support Specialist, Provincial Council for Maternal and Child Health The project team would like to thank the interview participants as well as the Better Outcomes Registry & Network (BORN) Ontario and the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences for supporting the data needs of this work. © 2018 Provincial Council for Maternal and Child Health Materials contained within this publication are copyright by the Provincial Council for Maternal and Child Health. Publications are intended for dissemination within and use by clinical networks. Reproduction or use of these materials for any other purpose requires the express written consent of the Provincial Council for Maternal and Child Health. Anyone seeking consent to reproduce materials in whole or in part, must seek permission of the Provincial Council for Maternal and Child Health by contacting [email protected]. Provincial Council for Maternal and Child Health 555 University Avenue Toronto, ON, M5G 1X8 [email protected] Maternal Newborn Gap Analysis | 2 Contents -

Temagami Area Backcountry Parks

7HPDJDPL $UHD /DG\(YHO\Q6PRRWKZDWHU 0DNREH*UD\V5LYHU 2EDELND5LYHU 6RODFH 6WXUJHRQ5LYHU 3DUN0DQDJHPHQW3ODQ © 2007, Queen’s Printer for Ontario Printed in Ontario, Canada Cover photo: Chee-bay-jing (Maple Mountain) in Lady Evelyn-Smoothwater Provincial Park The Ojibwe term “Chee-bay-jing” refers to the place where the sun sets—where life ends and the spirit dwells. This site is sacred to the First Nation communities of the Temagami area. Electronic copies of this publication are available at: http://www.ontarioparks.com/english/tema_planning.html Additional print copies of this publication are obtainable from the Ministry of Natural Resources at the Finlayson Point Provincial Park office: Finlayson Point Provincial Park P.O. Box 38 Temagami ON P0H 2H0 Telephone: (705) 569-3205 52090 (1.5k 31/07/07) ISBN 978-1-4249-4375-3 (Print) ISBN 978-1-4249-4376-0 (PDF) Printed on recycled paper Cette publication est également disponible en francais. Dear Sir/Madam: I am pleased to approve the Temagami Area Park Management Plan as the official policy for the protection and management of five parks in this significant area. The five parks are: Lady Evelyn-Smoothwater (wilderness class) Makobe-Grays River, Obabika River, Solace, and Sturgeon River (all waterway class parks). The plan reflects the Ministry of Natural Resources’ and Ontario Parks’ intent to protect the parks’ natural and cultural features while maintaining and enhancing high quality opportunities for outdoor recreation and heritage appreciation for the residents of Ontario and visitors to the Province. The plan includes implementation priorities and a summary of the public consultation that occurred as part of the planning process. -

Temagami Area Rock Art and Indigenous Routes

Zawadzka Temagami Area Rock Art 159 Beyond the Sacred: Temagami Area Rock Art and Indigenous Routes Dagmara Zawadzka The rock art of the Temagami area in northeastern Ontario represents one of the largest concentrations of this form of visual expression on the Canadian Shield. Created by Algonquian-speaking peoples, it is an inextricable part of their cultural landscape. An analysis of the distribution of 40 pictograph sites in relation to traditional routes known as nastawgan has revealed that an overwhelming majority are located on these routes, as well as near narrows, portages, or route intersections. Their location seems to point to their role in the navigation of the landscape. It is argued that rock art acted as a wayfinding landmark; as a marker of places linked to travel rituals; and, ultimately, as a sign of human occupation in the landscape. The tangible and intangible resources within which rock art is steeped demonstrate the relationships that exist among people, places, and the cultural landscape, and they point to the importance of this form of visual expression. Introduction interaction in the landscape. It may have served as The boreal forests of the Canadian Shield are a boundary, resource, or pathway marker. interspersed with places where pictographs have Therefore, it may have conveyed information that been painted with red ochre. Pictographs, located transcends the religious dimension of rock art and most often on vertical cliffs along lakes and rivers, of the landscape. are attributed to Algonquian-speaking peoples and This paper discusses the rock art of the attest, along with petroglyphs, petroforms, and Temagami area in northeastern Ontario in relation lichen glyphs, to a tradition that is at least 2000 to the traditional pathways of the area known as years old (Aubert et al. -

Hotspots Hiddengems

TEMISKAMING DISTRICT 2016 - 2017 HOTSPOTS HIDDEN &GEMS • North Bay • Temagami • Latchford • Cobalt • • Coleman • Temiskaming Shores • Haileybury • • New Liskeard • Dymond • Casey • Thornloe • • Earlton • Englehart • Elk Lake • Matachewan • • Gowganda • Kirkland Lake • photo MARCUS MARRIOTT 1500 FISHER STREET, NORTH BAY, ON NORTHGATESHOPPING.COM 2 Visitor’s Guide 2016 Temiskaming’s many treasures BY DARLENE WROE Wherever your trails take you in The treasures that can be found are Temiskaming, you will always fi nd reached through a way of looking and the peacefulness of nature and the appreciating. From the patch of wild friendliness of good people. strawberries along a sandy bank, to the high hanging wild fruit found along a Temiskaming’s history is both young and old. Inhabited by the First Nations riverbank, there is always something to people for thousands of years, the region appreciate. became home to the fi rst settlers around And in the towns the spirit of community the turn of the century. is always evident, and volunteerism is All people who live in the North love it a driving force that creates numerous for its grandeur, the open skies, the clean activities and adventures for people lakes, and the variety of wildlife that of all ages to enjoy. It’s just a matter of exists in every corner. looking. 1500 FISHER STREET, NORTH BAY, ON NORTHGATESHOPPING.COM photo JIM & LAURIE BOLESWORTH Visitor’s Guide 2016 3 LOCAL ART Wood Carvings Driftwood Decor Hand-Painted CUSTOM Decor Hey Visitors! WOOD FURNITURE Handmade Decor LANDSCAPING SUPPLIES -

A Global Transit Innovations (GTI) Data System

TRANSIT SERVICE FREQUENCY APP: A Global Transit Innovations (GTI) Data System Final Report Yingling Fan Humphrey School of Public Affairs University of Minnesota CTS 18-24 Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. 3. Recipients Accession No. CTS 18-24 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date TRANSIT SERVICE FREQUENCY APP: A Global Transit November 2018 Innovations (GTI) Data System 6. 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Yingling Fan, Peter Wiringa, Andrew Guthrie, Jingyu Ru, Tian He, Len Kne, and Shannon Crabtree 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Project/Task/Work Unit No. Humphrey School of Public Affairs University of Minnesota 11. Contract (C) or Grant (G) No. 301 19th Avenue South 295E Humphrey School Minneapolis MN 55455 12. Sponsoring Organization Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Center for Transportation Studies Final Report University of Minnesota 14. Sponsoring Agency Code University Office Plaza, Suite 440 2221 University Ave SE Minneapolis, MN 55414 15. Supplementary Notes http://www.cts.umn.edu/Publications/ResearchReports/ 16. Abstract (Limit: 250 words) The Transit Service Frequency App hosts stop- and alignment-level service frequency data from 559 transit providers around the globe who have published route and schedule data in the General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS) format through the TransitFeeds website, a global GTFS clearinghouse. Stop- and alignment-level service frequency is defined as the total number of transit routes and transit trips passing through a specific alignment segment or a specific stop location. Alignments are generalized and stops nearby stops aggregated. The app makes data easily accessible through visualization and download tools. -

Algoma University Bachelor of Arts in Geography (Honours)

Proposal for a Bachelor of Arts (BA) Four Year Honours Degree in Geography Submission to the Postsecondary Education Quality Assessment Board Algoma University Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario January 2011 Organization and Program Information Submission Title Page Full Legal Name of Organization: Algoma University Operating Name of Organization: Algoma University Common Acronym of Organization: AU URL for Organization Homepage: www.algomau.ca Proposed Degree Nomenclature: Bachelor of Arts in Geography (Honours) Location(s) where program to be delivered: Algoma University 1520 Queen Street East Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario P6A 2G4 Contact Information for Information about this submission: Arthur Perlini Dean and Associate Vice-President, Academic and Research 1520 Queen Street East Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario P6A 2G4 Tel: 705-949-2301 ext. 4116 Fax: 705-949-6583 Email: [email protected] Site Visit Coordinator: Dawn Elmore Academic Development and Project Coordinator 1520 Queen Street East Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario P6A 2G4 Tel: 705-949-2301 ext. 4372 Fax: 705-949-6583 Email: [email protected] Anticipated Start Date: September 2011 3 Table of Contents Organization and Program Information ............................................................................................................3 Submission Title Page ..............................................................................................................3 1. Introduction................................................................................................................................................................9 -

Ecosystems of Ontario, Part 1: Ecozones and Ecoregions

Science & Information Branch Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment Section The Ecosystems of Ontario, Part 1: Ecozones and Ecoregions Ministry of Natural Resources Science & Information Branch Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment Section Technical Report SIB TER IMA TR-01 The Ecosystems of Ontario, Part 1: Ecozones and Ecoregions By William J. Crins, Paul A. Gray, Peter W.C. Uhlig, and Monique C. Wester 2009 Ministry of Natural Resources ©2009, Queen’s Printer for Ontario Printed in Ontario, Canada ISBN 978-1-4435-0812-4 (Print) ISBN 978-1-4435-0813-1 (PDF) Single copies of this publication are available from: Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment 1235 Queen Street East Sault Ste. Marie, ON P6A 2E5 Cette publication spécialisée n’est disponible qu’en anglais This publication should be cited as: Crins, William J., Paul A. Gray, Peter W.C. Uhlig, and Monique C. Wester. 2009. The Ecosystems of Ontario, Part I: Ecozones and Ecoregions. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough Ontario, Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment, SIB TER IMA TR- 01, 71pp. Dedication This description of the broad-scale ecosystems of Ontario is dedicated to our cherished friend and colleague, Brenda Chambers, whose thorough knowledge of central Ontario’s ecosystems, environmental ethic, infectious enthusiasm, and positive outlook in the face of daunting challenges, have inspired us, and will continue to do so. Acknowledgments The authors respectfully acknowledge the many contributions of earlier authors Angus Hills, Dys Burger, Geoffrey Pierpoint, John Riley, and Stan Rowe whose work continues to provide the foundation for much of our understanding of the structure and function of Ontario’s diverse ecosystems. -

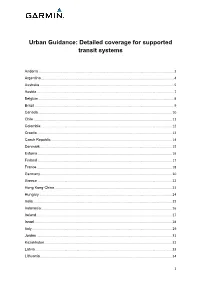

Urban Guidance: Detailed Coverage for Supported Transit Systems

Urban Guidance: Detailed coverage for supported transit systems Andorra .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Argentina ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Australia ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Austria .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Belgium .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Brazil ...................................................................................................................................................... 9 Canada ................................................................................................................................................ 10 Chile ..................................................................................................................................................... 11 Colombia .............................................................................................................................................. 12 Croatia ................................................................................................................................................. -

Accessible Transit Services in Ontario

Accessible transit services in Ontario Discussion paper ISBN – 0-7794-0652-4 Approved by the Commission: January 16, 2001 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 5 BACKGROUND.............................................................................................................. 5 PART I. TRANSIT AND HUMAN RIGHTS...................................................................... 7 1.1 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................. 7 1.2 THE ONTARIO HUMAN RIGHTS CODE.......................................................... 8 1.3 THE PROPOSED "ONTARIANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT" AND OTHER LEGISLATION ........................................................................................................... 10 1.4 CASE LAW ..................................................................................................... 11 1.5 THE AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT, 1990 (ADA)............................ 12 1.5.1 The ADA: Title II ...................................................................................... 13 PART II. METHODS OF ACHIEVING ACCESSIBILITY ............................................ 14 2.1 COMMUNITY BUSES AND SERVICE ROUTES............................................ 15 2.2 LOW FLOOR BUSES .................................................................................... -

Visitors-Guide.Pdf

Mayor’s Welcome 2020 has been a challenging year for all of us in different ways, but 2021 is full of possibilities! We hope the vaccines gives us hope for the future and get life back to normal so we all get the opportunity to enjoy our area this summer. As usual, we always look for the opportunity to WELCOME EVERYONE TO OUR BEAUTIFUL COMMUNITY! The Temagami Area, which incorporates the Town of Te- magami and Marten River, is surrounded by many lakes, including Lake Temagami. These lakes offer some of the finest fishing, boating, camping, canoeing, and hiking areas in North America. The area is also home to one of the last old growth forests in Ontario. Whatever brings you to Temagami, I encourage you to visit our many and varied tour- ist attractions. Be certain to visit our local shops to experience the friendly hospitality of our small town and the amazing talents of our many local art- ists and artisans. I encourage you to visit often and to stay a while. I am confident that once you do, the Temagami area will become one of your most enjoyed locations to visit, vacation, relax and once you do, no doubt you will want to return, often. - Mayor Dan O Experience Temagami, Make Your Stay An Adventure Welcome To Temagami … home of magnificent old growth pine forests, smooth blue waters, brilliantly white powder snow, and bountiful fish and wildlife. An outdoor enthusiasts’ paradise! Table of Contents 1 Essential Services Emergency 911 Nature at It’s Finest 2 Highway Information 511 Temagami Fire Tower 3 Ambulance Wishin’ You Were Fishin’/Temagami Petro/ Municipality of Temagami 4 Temagami 705-569-3434 Our Daily Bread/Century 21/Ojibway Family Lodge 5 Marten River 705-474-7400 Temagami Train Station 6 Fire Department Temagami 705-569-3232 Tourist Information Centre 7 Marten River 705-892-2280 History of Temagami 8 Forest Fires 888-863-3473 Marten River 9 Northland Traders/Temagami Property O.P.P. -

Rural Ontario Foresight Papers 2017

Rural Ontario Foresight Papers 2017 Rural Ontario Foresight Papers 2017 CONTENTS Foreword .................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Authors ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Growth Beyond Cities: Place-Based Rural Development Policy in Ontario .............................................. 7 Northern Perspectives – Place-Based Rural Policy Development in Ontario ........................................ 25 The Impact of Megatrends on Rural Development in Ontario: Progress through Foresight .......... 27 Northern Perspectives – The Impact of Megatrends on Rural Development in Ontario ................ 43 Broadband Infrastructure for the Future: Connecting Rural Ontario to the Digital Economy ....... 45 Northern Perspectives – Broadband Infrastructure for the Future ............................................................ 67 Rural Business Succession: Innovation Opportunities to Revitalize Local Communities ............... 71 Northern Perspectives – Rural Business Succession ......................................................................................... 89 Rural Volunteerism: How Well is the Heart of Community Doing? ............................................................ 93 Northern Perspectives – Rural Volunteerism .................................................................................................... -

Consultation Report: Human Rights and Public Transit Services in Ontario

HUMAN RIGHTS AND PUBLIC TRANSIT SERVICES IN ONTARIO Consultation Report ONTARIO HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION Approved by the Commission: Marcy 27, 2002 Available in various formats: IBM compatible computer disk, audio tape, large print Also available on Internet: www.ohrc.on.ca Disponible en français Transit Consultation Report I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..........................................................................3 II. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................4 III. SCOPE OF REPORT...............................................................................6 IV. KEY THEMES...............................................................................................7 V. TRANSIT SURVEY UPDATE..............................................................8 1. Background...........................................................................................................8 2. Plans and Standards ...........................................................................................8 3. Conventional Transit Systems ...........................................................................9 4. Paratransit Systems ..........................................................................................11 VI. CONVENTIONAL TRANSIT SYSTEMS...................................12 1. Conventional Transit Systems and Human Rights Law............................12 2. Accessible Conventional Transit Services in Ontario................................13 3. General Issues ..................................................................................................14