Basic Properties Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VISCOSITY of a GAS -Dr S P Singh Department of Chemistry, a N College, Patna

Lecture Note on VISCOSITY OF A GAS -Dr S P Singh Department of Chemistry, A N College, Patna A sketchy summary of the main points Viscosity of gases, relation between mean free path and coefficient of viscosity, temperature and pressure dependence of viscosity, calculation of collision diameter from the coefficient of viscosity Viscosity is the property of a fluid which implies resistance to flow. Viscosity arises from jump of molecules from one layer to another in case of a gas. There is a transfer of momentum of molecules from faster layer to slower layer or vice-versa. Let us consider a gas having laminar flow over a horizontal surface OX with a velocity smaller than the thermal velocity of the molecule. The velocity of the gaseous layer in contact with the surface is zero which goes on increasing upon increasing the distance from OX towards OY (the direction perpendicular to OX) at a uniform rate . Suppose a layer ‘B’ of the gas is at a certain distance from the fixed surface OX having velocity ‘v’. Two layers ‘A’ and ‘C’ above and below are taken into consideration at a distance ‘l’ (mean free path of the gaseous molecules) so that the molecules moving vertically up and down can’t collide while moving between the two layers. Thus, the velocity of a gas in the layer ‘A’ ---------- (i) = + Likely, the velocity of the gas in the layer ‘C’ ---------- (ii) The gaseous molecules are moving in all directions due= to −thermal velocity; therefore, it may be supposed that of the gaseous molecules are moving along the three Cartesian coordinates each. -

Equation of State for Benzene for Temperatures from the Melting Line up to 725 K with Pressures up to 500 Mpa†

High Temperatures-High Pressures, Vol. 41, pp. 81–97 ©2012 Old City Publishing, Inc. Reprints available directly from the publisher Published by license under the OCP Science imprint, Photocopying permitted by license only a member of the Old City Publishing Group Equation of state for benzene for temperatures from the melting line up to 725 K with pressures up to 500 MPa† MONIKA THOL ,1,2,* ERIC W. Lemm ON 2 AND ROLAND SPAN 1 1Thermodynamics, Ruhr-University Bochum, Universitaetsstrasse 150, 44801 Bochum, Germany 2National Institute of Standards and Technology, 325 Broadway, Boulder, Colorado 80305, USA Received: December 23, 2010. Accepted: April 17, 2011. An equation of state (EOS) is presented for the thermodynamic properties of benzene that is valid from the triple point temperature (278.674 K) to 725 K with pressures up to 500 MPa. The equation is expressed in terms of the Helmholtz energy as a function of temperature and density. This for- mulation can be used for the calculation of all thermodynamic properties. Comparisons to experimental data are given to establish the accuracy of the EOS. The approximate uncertainties (k = 2) of properties calculated with the new equation are 0.1% below T = 350 K and 0.2% above T = 350 K for vapor pressure and liquid density, 1% for saturated vapor density, 0.1% for density up to T = 350 K and p = 100 MPa, 0.1 – 0.5% in density above T = 350 K, 1% for the isobaric and saturated heat capaci- ties, and 0.5% in speed of sound. Deviations in the critical region are higher for all properties except vapor pressure. -

Determination of the Identity of an Unknown Liquid Group # My Name the Date My Period Partner #1 Name Partner #2 Name

Determination of the Identity of an unknown liquid Group # My Name The date My period Partner #1 name Partner #2 name Purpose: The purpose of this lab is to determine the identity of an unknown liquid by measuring its density, melting point, boiling point, and solubility in both water and alcohol, and then comparing the results to the values for known substances. Procedure: 1) Density determination Obtain a 10mL sample of the unknown liquid using a graduated cylinder Determine the mass of the 10mL sample Save the sample for further use 2) Melting point determination Set up an ice bath using a 600mL beaker Obtain a ~5mL sample of the unknown liquid in a clean dry test tube Place a thermometer in the test tube with the sample Place the test tube in the ice water bath Watch for signs of crystallization, noting the temperature of the sample when it occurs Save the sample for further use 3) Boiling point determination Set up a hot water bath using a 250mL beaker Begin heating the water in the beaker Obtain a ~10mL sample of the unknown in a clean, dry test tube Add a boiling stone to the test tube with the unknown Open the computer interface software, using a graph and digit display Place the temperature sensor in the test tube so it is in the unknown liquid Record the temperature of the sample in the test tube using the computer interface Watch for signs of boiling, noting the temperature of the unknown Dispose of the sample in the assigned waste container 4) Solubility determination Obtain two small (~1mL) samples of the unknown in two small test tubes Add an equal amount of deionized into one of the samples Add an equal amount of ethanol into the other Mix both samples thoroughly Compare the samples for solubility Dispose of the samples in the assigned waste container Observations: The unknown is a clear, colorless liquid. -

Viscosity of Gases References

VISCOSITY OF GASES Marcia L. Huber and Allan H. Harvey The following table gives the viscosity of some common gases generally less than 2% . Uncertainties for the viscosities of gases in as a function of temperature . Unless otherwise noted, the viscosity this table are generally less than 3%; uncertainty information on values refer to a pressure of 100 kPa (1 bar) . The notation P = 0 specific fluids can be found in the references . Viscosity is given in indicates that the low-pressure limiting value is given . The dif- units of μPa s; note that 1 μPa s = 10–5 poise . Substances are listed ference between the viscosity at 100 kPa and the limiting value is in the modified Hill order (see Introduction) . Viscosity in μPa s 100 K 200 K 300 K 400 K 500 K 600 K Ref. Air 7 .1 13 .3 18 .5 23 .1 27 .1 30 .8 1 Ar Argon (P = 0) 8 .1 15 .9 22 .7 28 .6 33 .9 38 .8 2, 3*, 4* BF3 Boron trifluoride 12 .3 17 .1 21 .7 26 .1 30 .2 5 ClH Hydrogen chloride 14 .6 19 .7 24 .3 5 F6S Sulfur hexafluoride (P = 0) 15 .3 19 .7 23 .8 27 .6 6 H2 Normal hydrogen (P = 0) 4 .1 6 .8 8 .9 10 .9 12 .8 14 .5 3*, 7 D2 Deuterium (P = 0) 5 .9 9 .6 12 .6 15 .4 17 .9 20 .3 8 H2O Water (P = 0) 9 .8 13 .4 17 .3 21 .4 9 D2O Deuterium oxide (P = 0) 10 .2 13 .7 17 .8 22 .0 10 H2S Hydrogen sulfide 12 .5 16 .9 21 .2 25 .4 11 H3N Ammonia 10 .2 14 .0 17 .9 21 .7 12 He Helium (P = 0) 9 .6 15 .1 19 .9 24 .3 28 .3 32 .2 13 Kr Krypton (P = 0) 17 .4 25 .5 32 .9 39 .6 45 .8 14 NO Nitric oxide 13 .8 19 .2 23 .8 28 .0 31 .9 5 N2 Nitrogen 7 .0 12 .9 17 .9 22 .2 26 .1 29 .6 1, 15* N2O Nitrous -

The Basics of Vapor-Liquid Equilibrium (Or Why the Tripoli L2 Tech Question #30 Is Wrong)

The Basics of Vapor-Liquid Equilibrium (Or why the Tripoli L2 tech question #30 is wrong) A question on the Tripoli L2 exam has the wrong answer? Yes, it does. What is this errant question? 30.Above what temperature does pressurized nitrous oxide change to a gas? a. 97°F b. 75°F c. 37°F The correct answer is: d. all of the above. The answer that is considered correct, however, is: a. 97ºF. This is the critical temperature above which N2O is neither a gas nor a liquid; it is a supercritical fluid. To understand what this means and why the correct answer is “all of the above” you have to know a little about the behavior of liquids and gases. Most people know that water boils at 212ºF. Most people also know that when you’re, for instance, boiling an egg in the mountains, you have to boil it longer to fully cook it. The reason for this has to do with the vapor pressure of water. Every liquid wants to vaporize to some extent. The measure of this tendency is known as the vapor pressure and varies as a function of temperature. When the vapor pressure of a liquid reaches the pressure above it, it boils. Until then, it evaporates until the fraction of vapor in the mixture above it is equal to the ratio of the vapor pressure to the total pressure. At that point it is said to be in equilibrium and no further liquid will evaporate. The vapor pressure of water at 212ºF is 14.696 psi – the atmospheric pressure at sea level. -

Liquid-Vapor Equilibrium in a Binary System

Liquid-Vapor Equilibria in Binary Systems1 Purpose The purpose of this experiment is to study a binary liquid-vapor equilibrium of chloroform and acetone. Measurements of liquid and vapor compositions will be made by refractometry. The data will be treated according to equilibrium thermodynamic considerations, which are developed in the theory section. Theory Consider a liquid-gas equilibrium involving more than one species. By definition, an ideal solution is one in which the vapor pressure of a particular component is proportional to the mole fraction of that component in the liquid phase over the entire range of mole fractions. Note that no distinction is made between solute and solvent. The proportionality constant is the vapor pressure of the pure material. Empirically it has been found that in very dilute solutions the vapor pressure of solvent (major component) is proportional to the mole fraction X of the solvent. The proportionality constant is the vapor pressure, po, of the pure solvent. This rule is called Raoult's law: o (1) psolvent = p solvent Xsolvent for Xsolvent = 1 For a truly ideal solution, this law should apply over the entire range of compositions. However, as Xsolvent decreases, a point will generally be reached where the vapor pressure no longer follows the ideal relationship. Similarly, if we consider the solute in an ideal solution, then Eq.(1) should be valid. Experimentally, it is generally found that for dilute real solutions the following relationship is obeyed: psolute=K Xsolute for Xsolute<< 1 (2) where K is a constant but not equal to the vapor pressure of pure solute. -

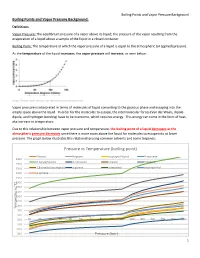

Pressure Vs Temperature (Boiling Point)

Boiling Points and Vapor Pressure Background Boiling Points and Vapor Pressure Background: Definitions Vapor Pressure: The equilibrium pressure of a vapor above its liquid; the pressure of the vapor resulting from the evaporation of a liquid above a sample of the liquid in a closed container. Boiling Point: The temperature at which the vapor pressure of a liquid is equal to the atmospheric (or applied) pressure. As the temperature of the liquid increases, the vapor pressure will increase, as seen below: https://www.chem.purdue.edu/gchelp/liquids/vpress.html Vapor pressure is interpreted in terms of molecules of liquid converting to the gaseous phase and escaping into the empty space above the liquid. In order for the molecules to escape, the intermolecular forces (Van der Waals, dipole- dipole, and hydrogen bonding) have to be overcome, which requires energy. This energy can come in the form of heat, aka increase in temperature. Due to this relationship between vapor pressure and temperature, the boiling point of a liquid decreases as the atmospheric pressure decreases since there is more room above the liquid for molecules to escape into at lower pressure. The graph below illustrates this relationship using common solvents and some terpenes: Pressure vs Temperature (boiling point) Ethanol Heptane Isopropyl Alcohol B-myrcene 290.0 B-caryophyllene d-Limonene Linalool Pulegone 270.0 250.0 1,8-cineole (eucalyptol) a-pinene a-terpineol terpineol-4-ol 230.0 p-cymene 210.0 190.0 170.0 150.0 130.0 110.0 90.0 Temperature (˚C) Temperature 70.0 50.0 30.0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 200 300 400 500 600 760 10.0 -10.0 -30.0 Pressure (torr) 1 Boiling Points and Vapor Pressure Background As a very general rule of thumb, the boiling point of many liquids will drop about 0.5˚C for a 10mmHg decrease in pressure when operating in the region of 760 mmHg (atmospheric pressure). -

Specific Latent Heat

SPECIFIC LATENT HEAT The specific latent heat of a substance tells us how much energy is required to change 1 kg from a solid to a liquid (specific latent heat of fusion) or from a liquid to a gas (specific latent heat of vaporisation). �����푦 (��) 퐸 ����������푐 ������� ℎ���� �� ������� �� = (��⁄��) = 푓 � ����� (��) �����푦 = ����������푐 ������� ℎ���� �� 퐸 = ��푓 × � ������� × ����� ����� 퐸 � = �� 푦 푓 ����� = ����������푐 ������� ℎ���� �� ������� WORKED EXAMPLE QUESTION 398 J of energy is needed to turn 500 g of liquid nitrogen into at gas at-196°C. Calculate the specific latent heat of vaporisation of nitrogen. ANSWER Step 1: Write down what you know, and E = 99500 J what you want to know. m = 500 g = 0.5 kg L = ? v Step 2: Use the triangle to decide how to 퐸 ��푣 = find the answer - the specific latent heat � of vaporisation. 99500 퐽 퐿 = 0.5 �� = 199 000 ��⁄�� Step 3: Use the figures given to work out 푣 the answer. The specific latent heat of vaporisation of nitrogen in 199 000 J/kg (199 kJ/kg) Questions 1. Calculate the specific latent heat of fusion if: a. 28 000 J is supplied to turn 2 kg of solid oxygen into a liquid at -219°C 14 000 J/kg or 14 kJ/kg b. 183 600 J is supplied to turn 3.4 kg of solid sulphur into a liquid at 115°C 54 000 J/kg or 54 kJ/kg c. 6600 J is supplied to turn 600g of solid mercury into a liquid at -39°C 11 000 J/kg or 11 kJ/kg d. -

Freezing and Boiling Point Changes

Freezing Point and Boiling Point Changes for Solutions and Solids Lesson Plans and Labs By Ranald Bleakley Physics and Chemistry teacher Weedsport Jnr/Snr High School RET 2 Cornell Center for Materials Research Summer 2005 Freezing Point and Boiling Point Changes for Solutions and Solids Lesson Plans and Labs Summary: Major skills taught: • Predicting changes in freezing and boiling points of water, given type and quantity of solute added. • Solving word problems for changes to boiling points and freezing points of solutions based upon data supplied. • Application of theory to real samples in lab to collect and analyze data. Students will describe the importance to industry of the depression of melting points in solids such as metals and glasses. • Students will describe and discuss the evolution of glass making through the ages and its influence on social evolution. Appropriate grade and level: The following lesson plans and labs are intended for instruction of juniors or seniors enrolled in introductory chemistry and/or physics classes. It is most appropriately taught to students who have a basic understanding of the properties of matter and of solutions. Mathematical calculations are intentionally kept to a minimum in this unit and focus is placed on concepts. The overall intent of the unit is to clarify the relationship between changes to the composition of a mixture and the subsequent changes in the eutectic properties of that mixture. Theme: The lesson plans and labs contained in this unit seek to teach and illustrate the concepts associated with the eutectic of both liquid solutions, and glasses The following people have been of great assistance: Professor Louis Hand Professor of Physics. -

Methods for the Determination of the Normal Boiling Point of a High

Metalworking Fluids & VOC, Today and Tomorrow A Joint Symposium by SCAQMD & ILMA South Coast Air Quality Management District Diamond Bar, CA, USA March 8, 2012 Understanding & Determining the Normal Boiling Point of a High Boiling Liquid Presentation Outline • Relationship of Vapor Pressure to Temperature • Examples of VP/T Curves • Calculation of Airborne Vapor Concentration • Binary Systems • Relative Volatility as a function of Temperature • GC Data and Volatility • Everything Needs a Correlation • Conclusions Vapor Pressure Models (pure vapor over pure liquid) Correlative: • Clapeyron: Log(P) = A/T + B • Antoine: Log(P) = A/(T-C) + B • Riedel: LogP = A/T + B + Clog(T) + DTE Predictive: • ACD Group Additive Methods • Riedel: LogP = A/T + B + Clog(T) + DTE Coefficients defined, Reduced T = T/Tc • Variations: Frost-Kalkwarf-Thodos, etc. Two Parameters: Log(P) = A/T + B Vaporization as an CH OH(l) CH OH(g) activated process 3 3 G = -RTln(K) = -RTln(P) K = [CH3OH(g)]/[CH3OH(l)] G = H - TS [CH3OH(g)] = partial P ln(P) = -G/RT [CH3OH(l)] = 1 (pure liquid) ln(P) = -H/RT+ S/R K = P S/R = B ln(P) = ln(K) H/R = -A Vapor pressure Measurement: Direct versus Distillation • Direct vapor pressure measurement (e.g., isoteniscope) requires pure material while distillation based determination can employ a middle cut with a relatively high purity. Distillation allows for extrapolation and/or interpolation of data to approximate VP. • Direct vapor pressure measurement requires multiple freeze-thaw cycles to remove atmospheric gases while distillation (especially atmospheric distillation) purges atmospheric gases as part of the process. • Direct measurement OK for “volatile materials” (normal BP < 100 oC) but involved for “high boilers” (normal BP > 100 oC). -

Chapter 3 3.4-2 the Compressibility Factor Equation of State

Chapter 3 3.4-2 The Compressibility Factor Equation of State The dimensionless compressibility factor, Z, for a gaseous species is defined as the ratio pv Z = (3.4-1) RT If the gas behaves ideally Z = 1. The extent to which Z differs from 1 is a measure of the extent to which the gas is behaving nonideally. The compressibility can be determined from experimental data where Z is plotted versus a dimensionless reduced pressure pR and reduced temperature TR, defined as pR = p/pc and TR = T/Tc In these expressions, pc and Tc denote the critical pressure and temperature, respectively. A generalized compressibility chart of the form Z = f(pR, TR) is shown in Figure 3.4-1 for 10 different gases. The solid lines represent the best curves fitted to the data. Figure 3.4-1 Generalized compressibility chart for various gases10. It can be seen from Figure 3.4-1 that the value of Z tends to unity for all temperatures as pressure approach zero and Z also approaches unity for all pressure at very high temperature. If the p, v, and T data are available in table format or computer software then you should not use the generalized compressibility chart to evaluate p, v, and T since using Z is just another approximation to the real data. 10 Moran, M. J. and Shapiro H. N., Fundamentals of Engineering Thermodynamics, Wiley, 2008, pg. 112 3-19 Example 3.4-2 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- A closed, rigid tank filled with water vapor, initially at 20 MPa, 520oC, is cooled until its temperature reaches 400oC. -

Liquid Equilibrium Measurements in Binary Polar Systems

DIPLOMA THESIS VAPOR – LIQUID EQUILIBRIUM MEASUREMENTS IN BINARY POLAR SYSTEMS Supervisors: Univ. Prof. Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Anton Friedl Associate Prof. Epaminondas Voutsas Antonia Ilia Vienna 2016 Acknowledgements First of all I wish to thank Doctor Walter Wukovits for his guidance through the whole project, great assistance and valuable suggestions for my work. I have completed this thesis with his patience, persistence and encouragement. Secondly, I would like to thank Professor Anton Friedl for giving me the opportunity to work in TU Wien and collaborate with him and his group for this project. I am thankful for his trust from the beginning until the end and his support during all this period. Also, I wish to thank for his readiness to help and support Professor Epaminondas Voutsas, who gave me the opportunity to carry out this thesis in TU Wien, and his valuable suggestions and recommendations all along the experimental work and calculations. Additionally, I would like to thank everybody at the office and laboratory at TU Wien for their comprehension and selfless help for everything I needed. Furthermore, I wish to thank Mersiha Gozid and all the students of Chemical Engineering Summer School for their contribution of data, notices, questions and solutions during my experimental work. And finally, I would like to thank my family and friends for their endless support and for the inspiration and encouragement to pursue my goals and dreams. Abstract An experimental study was conducted in order to investigate the vapor – liquid equilibrium of binary mixtures of Ethanol – Butan-2-ol, Methanol – Ethanol, Methanol – Butan-2-ol, Ethanol – Water, Methanol – Water, Acetone – Ethanol and Acetone – Butan-2-ol at ambient pressure using the dynamic apparatus Labodest VLE 602.