Double Burden of Malnutrition Crisis And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fitch Connect

Fitch Connect An innovative, robust and comprehensive credit analytics and macro intelligence platform designed to service the individual data consumption models of credit risk, debt market and strategic research professionals. fitchconnect.com | fitchsolutions.com Fitch Connect Fitch Connect is a credit risk and macro intelligence platform from Fitch Solutions providing credit research, credit ratings, macroeconomic and financial fundamental data, country risk research and indices, Financial Implied Ratings and a curated news service. Business Benefits Manage credit risk with greater efficiency, clarity and ease Benchmark analysis against Fitch Ratings comprehensive credit across the enterprise using a single platform supporting risk view through a comprehensive suite of market-based credit multiple delivery channels depending on your preferred data risk indicators. Keep informed of credit risk trends through consumption model. accessing information and data updated each day. New client- initiated entities can be added within a few days. Meet specific credit, debt market and macroeconomic analysis needs with an integrated, standardized and custom data feed Use transparent credit information covering the broadest range that can easily be imported into various software applications of entities, to help manage regulatory and capital adequacy and models. reporting requirements and leverage credit research insight into the ratings given by Fitch Ratings analysts. Key Capabilities Access the full research output and credit ratings from Fitch Evaluate country risk and other external factors including Ratings with its 25 distinct rating types that include recovery, geopolitical and operational risks using Country Risk Research and country ceiling, and volatility and viability ratings. Country Risk Indices and access macroeconomic data for more Estimate the likelihood of default based on an evidence-based than 200 global economies including up to 1,500 data series per assessment of risk using historical ratings, outlooks and watch market and a 10- year forecast. -

Frieslandcampina WAMCO 2014 Annual Report

table of contents GeneRal 4 Financial highlights 5 Corporate directory 8 Notice of annual general meeting 11 Chairman’s statement 16 The board of directors RepoRts and financial statements 22 Directors, professional advisers and registered office 23 Report of the directors 31 Statement of directors’ responsibilities 32 Report of the audit committee 33 Independent auditor’s report 34 Financial statements 75 Other information 81 Proxy form Financial highlights for the year ended 31 December 2014 2014 2013 % Increase/ =N=’000 =N=’000 (Decrease) Revenue 126,436,219 120,256,164 5.14 Profit before income tax 16,499,920 19,312,554 -14.56 Profit for the year 10,731,278 13,069,521 -17.89 Share Capital 488,168 488,168 0.00 Total equity 9,559,249 8,643,282 10.60 Per Share Data Number of 50k Ordinary Shares 976,335,936 976,335,936 0.00 Basic earnings 10.99 13.39 -17.92 1st interim dividend paid 3.91 5.20 -24.81 2nd interim dividend paid 0.00 2.57 -100.00 Final dividend proposed 4.33 5.68 -23.77 Number of employees 844 829 1.81 4 FrieslandCampina WAMCO Nigeria PLC 2014 Annual Report corporate directory Head office aba regional office FrieslandCampina WAMCO Nigeria PLC c/o CFAO (Nig.) PLC Plot 7b Acme Road 4 Factory Road Ikeja Industrial Estate Aba Ogba -Ikeja Abia State Lagos State Tel: + 234 (01) 271 5100 asaba regional office [email protected] www.frieslandcampina.com.ng Km 5 Benin / Asaba Expressway Behinde Oblinks Filling Station lagos/ogun sales office Asaba Delta State Plot 3b Acme Road Ikeja Industrial Estate abuja regional office Ogba – Ikeja Lagos State Plot 1077, Durumi by Area 3 Junction Garki ibadan regional office Abuja c/o CFAO (Nig.) PLC Kano regional office 59 Onireke Street, Dugbe Alawo c/o CFAO (Nig.) PLC Dugbe – Alawo 12 Muritala Mohammed Way Ibadan Kano Oyo State Kano state Gombe regional office Commercial Area Plot BA/4358 Gombe, Gombe State 5 since 1954, frieslandcampina WAMCO, the number one nutrition company in nigeria, has always been dedicated to the wellbeing of nigerians. -

AMS112 1978-1979 Lowres Web

--~--------~--------------------------------------------~~~~----------~-------------- - ~------------------------------ COVER: Paul Webber, technical officer in the Herpetology department searchers for reptiles and amphibians on a field trip for the Colo River Survey. Photo: John Fields!The Australian Museum. REPORT of THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM TRUST for the YEAR ENDED 30 JUNE , 1979 ST GOVERNMENT PRINTER, NEW SOUTH WALES-1980 D. WE ' G 70708K-1 CONTENTS Page Page Acknowledgements 4 Department of Palaeontology 36 The Australian Museum Trust 5 Department of Terrestrial Invertebrate Ecology 38 Lizard Island Research Station 5 Department of Vertebrate Ecology 38 Research Associates 6 Camden Haven Wildlife Refuge Study 39 Associates 6 Functional Anatomy Unit.. 40 National Photographic Index of Australian Director's Research Laboratory 40 Wildlife . 7 Materials Conservation Section 41 The Australian Museum Society 7 Education Section .. 47 Letter to the Premier 9 Exhibitions Department 52 Library 54 SCIENTIFIC DEPARTMENTS Photographic and Visual Aid Section 54 Department of Anthropology 13 PublicityJ Pu bl ications 55 Department of Arachnology 18 National Photographic Index of Australian Colo River Survey .. 19 Wildlife . 57 Lizard Island Research Station 59 Department of Entomology 20 The Australian Museum Society 61 Department of Herpetology 23 Appendix 1- Staff .. 62 Department of Ichthyology 24 Appendix 2-Donations 65 Department of Malacology 25 Appendix 3-Acknowledgements of Co- Department of Mammalogy 27 operation. 67 Department of Marine -

Captain Bligh

www.goglobetrotting.com THE MAGAZINE FOR WORLD TRAVELLERS - SPRING/SUMMER 2014 CANADIAN EDITION - No. 20 CONTENTS Iceland-Awesome Destination. 3 New Faces of Goway. 4 Taiwan: Foodie's Paradise. 5 Historic Henan. 5 Why Southeast Asia? . 6 The mutineers turning Bligh and his crew from the 'Bounty', 29th April 1789. The revolt came as a shock to Captain Bligh. Bligh and his followers were cast adrift without charts and with only meagre rations. They were given cutlasses but no guns. Yet Bligh and all but one of the men reached Timor safely on 14 June 1789. The journey took 47 days. Captain Bligh: History's Most Philippines. 6 Misunderstood Globetrotter? Australia on Sale. 7 by Christian Baines What transpired on the Bounty Captain’s Servant on the HMS contact with the Hawaiian Islands, Downunder Self Drive. 8 Those who owe everything they is just one chapter of Bligh’s story, Monmouth. The industrious where a dispute with the natives Spirit of Queensland. 9 know about Captain William Bligh one that for the most-part tells of young recruit served on several would end in the deaths of Cook Exploring Egypt. 9 to Hollywood could be forgiven for an illustrious naval career and of ships before catching the attention and four Marines. This tragedy Ecuador's Tren Crucero. 10 thinking the man was a sociopath. a leader noted for his fairness and of Captain James Cook, the first however, led to Bligh proving him- South America . 10 In many versions of the tale, the (for the era) clemency. Bligh’s tem- European to set foot on the east self one of the British Navy’s most man whose leadership drove the per however, frequently proved his coast of Australia. -

Frieslandcampina Annual Report 2011

Annual Report 2011 Annual Annual Report 2011 Royal FrieslandCampina N.V. | Royal FrieslandCampina N.V. FrieslandCampina Royal 1 Annual Report 2011 Royal FrieslandCampina N.V. Caption on cover: Milk is one of the richest natural sources of essential nutrients. The nutritional power of milk is the basis on which FrieslandCampina provides consumers around the world with healthy, sustainably produced food. 2 Explanatory note In this Annual Report we are presenting the financial results and key developments of Royal FrieslandCampina N.V. (hereafter FrieslandCampina) during 2011. The financial statements have been prepared as at 31 December 2011. The figures for 2011 and the comparative figures for 2010 have been prepared in accordance with the International Financial Reporting Standards to the extent they have been endorsed by the European Union (EU-IFRS). The milk price for 2011 received by members of Zuivelcoöperatie FrieslandCampina U.A. for the milk they supplied was determined on the basis of FrieslandCampina’s method for determining milk prices 2011 – 2013. All amounts in this report are in euros, unless stated otherwise. This Annual Report includes statements about future expectations. These statements are based on the current expectations, estimates and projections of FrieslandCampina’s management and the information currently available. The expectations are uncertain and contain elements of risk that are difficult to quantify. For this reason FrieslandCampina gives no assurance that the expectations will be realised. The Annual Report of Royal FrieslandCampina N.V. has also been published on the website www.frieslandcampina.com and is available on request from the Corporate Communication department of FrieslandCampina ([email protected]). -

Becoming Art: Some Relationships Between Pacific Art and Western Culture Susan Cochrane University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1995 Becoming art: some relationships between Pacific art and Western culture Susan Cochrane University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Cochrane, Susan, Becoming art: some relationships between Pacific ra t and Western culture, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, , University of Wollongong, 1995. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/2088 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. BECOMING ART: SOME RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN PACIFIC ART AND WESTERN CULTURE by Susan Cochrane, B.A. [Macquarie], M.A.(Hons.) [Wollongong] 203 CHAPTER 4: 'REGIMES OF VALUE'1 Bokken ngarribimbun dorlobbo: ngarrikarrme gunwok kunmurrngrayek ngadberre ngarribimbun dja mak kunwarrde kne ngarribimbun. (There are two reasons why we do our art: the first is to maintain our culture, the second is to earn money). Injalak Arts and Crafts Corporate Plan INTRODUCTION In the last chapter, the example of bark paintings was used to test Western categories for indigenous art. Reference was also made to Aboriginal systems of classification, in particular the ways Yolngu people classify painting, including bark painting. Morphy's concept, that Aboriginal art exists in two 'frames', was briefly introduced, and his view was cited that Yolngu artists increasingly operate within both 'frames', the Aboriginal frame and the European frame (Morphy 1991:26). This chapter develops the theme of how indigenous art objects are valued, both within the creator society and when they enter the Western art-culture system. When aesthetic objects move between cultures the values attached to them may change. -

FUTURE of FOOD a Lighthouse for Future Living, Today Context + People and Market Insights + Emerging Innovations

FUTURE OF FOOD A Lighthouse for future living, today Context + people and market insights + emerging innovations Home FUTURE OF FOOD | 01 FOREWORD: CREATING THE FUTURE WE WANT If we are to create a world in which 9 billion to spend. That is the reality of the world today. people live well within planetary boundaries, People don’t tend to aspire to less. “ WBCSD is committed to creating a then we need to understand why we live sustainable world – one where 9 billion Nonetheless, we believe that we can work the way we do today. We must understand people can live well, within planetary within this reality – that there are huge the world as it is, if we are to create a more boundaries. This won’t be achieved opportunities available, for business all over sustainable future. through technology alone – it is going the world, and for sustainable development, The cliché is true: we live in a fast-changing in designing solutions for the world as it is. to involve changing the way we live. And world. Globally, people are both choosing, and that’s a good thing – human history is an This “Future of” series from WBCSD aims to having, to adapt their lifestyles accordingly. endless journey of change for the better. provide a perspective that helps to uncover While no-one wants to live unsustainably, and Forward-looking companies are exploring these opportunities. We have done this by many would like to live more sustainably, living how we can make sustainable living looking at the way people need and want to a sustainable lifestyle isn’t a priority for most both possible and desirable, creating live around the world today, before imagining people around the world. -

The Dealership of Tomorrow 2.0: America’S Car Dealers Prepare for Change

The Dealership of Tomorrow 2.0: America’s Car Dealers Prepare for Change February 2020 An independent study by Glenn Mercer Prepared for the National Automobile Dealers Association The Dealership of Tomorrow 2.0 America’s Car Dealers Prepare for Change by Glenn Mercer Introduction This report is a sequel to the original Dealership of Tomorrow: 2025 (DOT) report, issued by NADA in January 2017. The original report was commissioned by NADA in order to provide its dealer members (the franchised new-car dealers of America) perspectives on the changing automotive retailing environment. The 2017 report was intended to offer “thought starters” to assist dealers in engaging in strategic planning, looking ahead to roughly 2025.1 In early 2019 NADA determined it was time to update the report, as the environment was continuing to shift. The present document is that update: It represents the findings of new work conducted between May and December of 2019. As about two and a half years have passed since the original DOT, focused on 2025, was issued, this update looks somewhat further out, to the late 2020s. Disclaimers As before, we need to make a few things clear at the outset: 1. In every case we have tried to link our forecast to specific implications for dealers. There is much to be said about the impact of things like electric vehicles and connected cars on society, congestion, the economy, etc. But these impacts lie far beyond the scope of this report, which in its focus on dealerships is already significant in size. Readers are encouraged to turn to academic, consulting, governmental and NGO reports for discussion of these broader issues. -

Frieslandcampina Annual Report 2009

Annual report 2009 Royal FrieslandCampina N.V. Stationsplein 4 3818 LE Amersfoort The Netherlands T +31 33 713 3333 www.frieslandcampina.com | Royal FrieslandCampina N.V. FrieslandCampina | Royal Annual report 2009 Royal FrieslandCampina N.V. Annual report 2009 Royal FrieslandCampina N.V. Explanatory note In this Annual report we present the financial The financial statements have been prepared as at performance and key developments of Royal 31 December 2009. The figures for 2009 and the FrieslandCampina N.V. in 2009. comparative figures for 2008 have been prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting We also invite you to read, in a number of brief Standards to the extent endorsed by the European interviews, about how some of our employees and Union (EU-IFRS). The milk price for 2009 has been member dairy farmers feel about 2009. It was an determined on the basis of FrieslandCampina’s method eventful year for many, because of the consequences of for determining milk prices. the financial and economic crisis, the decreased selling prices for dairy products and the amalgamation of the The Annual report of Royal FrieslandCampina N.V. companies following the merger between Friesland has been posted on www.frieslandcampina.com Foods and Campina. and is available upon request from the Corporate Communication Department of FrieslandCampina. This Annual report appears in Dutch, German and English. Only the Dutch text is legally binding, as it is the authentic text. The English text is included as a translation for convenience -

Healthy Living News and Research Update

Healthy Living News and Research Update June 6, 2017 The materials provided in this document are intended to inform and support those groups that are implementing the SelectHealth Healthy Living product as part of their employee wellness program. You will be receiving similar updates twice each month. If you would prefer not to receive these regular updates please let me know. We welcome your feedback and suggestions. Best Regards, Tim Tim Butler, MS, MCHES Senior Wellness Program Management Consultant 801-442-7397 [email protected] __________________________________________________________________________________________________ Healthy Living Program Updates • Registration for the Next Core Activity Challenge Begins 6/21 Upcoming Wellness Events • Utah Worksite Wellness Council “Time Out for Wellness” Networking Event Workplace Wellness • Change at Work Linked to Employee Stress, Distrust and Intent to Quit, New Survey Finds • How Leaders Can Push Employees Without Stressing Them Out • Retirement savings gap seen reaching $400 trillion by 2050 • High-deductible health plans promote increased wellness program participation • Hospital system becomes Blue Zones standout • Healthy Higher Ed Employees • Best Practices for Using Wearable Devices in Wellness Programs • High-deductible, consumer-driven health plans keep growing • Pay the medical bills or save for retirement? • 5 cheap ways to get healthy before you're old enough to retire • Views: 3 ways companies can help tackle mental health issues • Why Lower Health Care Costs -

Annual Copyright License for Corporations

Responsive Rights - Annual Copyright License for Corporations Publisher list Specific terms may apply to some publishers or works. Please refer to the Annual Copyright License search page at http://www.copyright.com/ to verify publisher participation and title coverage, as well as any applicable terms. Participating publishers include: Advance Central Services Advanstar Communications Inc. 1105 Media, Inc. Advantage Business Media 5m Publishing Advertising Educational Foundation A. M. Best Company AEGIS Publications LLC AACC International Aerospace Medical Associates AACE-Assn. for the Advancement of Computing in Education AFCHRON (African American Chronicles) AACECORP, Inc. African Studies Association AAIDD Agate Publishing Aavia Publishing, LLC Agence-France Presse ABC-CLIO Agricultural History Society ABDO Publishing Group AHC Media LLC Abingdon Press Ahmed Owolabi Adesanya Academy of General Dentistry Aidan Meehan Academy of Management (NY) Airforce Historical Foundation Academy Of Political Science Akademiai Kiado Access Intelligence Alan Guttmacher Institute ACM (Association for Computing Machinery) Albany Law Review of Albany Law School Acta Ecologica Sinica Alcohol Research Documentation, Inc. Acta Oceanologica Sinica Algora Publishing ACTA Publications Allerton Press Inc. Acta Scientiae Circumstantiae Allied Academies Inc. ACU Press Allied Media LLC Adenine Press Allured Business Media Adis Data Information Bv Allworth Press / Skyhorse Publishing Inc Administrative Science Quarterly AlphaMed Press 9/8/2015 AltaMira Press American -

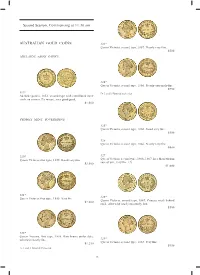

Second Session, Commencing at 11.30 Am AUSTRALIAN GOLD

Second Session, Commencing at 11.30 am AUSTRALIAN GOLD COINS 323* Queen Victoria, second type, 1857. Nearly very fi ne. $500 ADELAIDE ASSAY OFFICE 324* Queen Victoria, second type, 1866. Nearly extremely fi ne. $750 319* Ex J. and J. Edwards Collection. Adelaide pound, 1852, second type with crenellated inner circle on reverse. Ex mount, very good/good. $1,000 SYDNEY MINT SOVEREIGNS 325* Queen Victoria, second type, 1866. Good very fi ne. $500 326 Queen Victoria, second type, 1866. Nearly very fi ne. $400 320* 327 Queen Victoria, fi rst type, 1855. Good very fi ne. Queen Victoria, second type, 1866, 1867. In a Monetarium case of sale, very fi ne. (2) $3,000 $1,000 321* 328* Queen Victoria, fi rst type, 1855. Very fi ne. Queen Victoria, second type, 1867. Contact mark behind $2,000 neck, otherwise nearly extremely fi ne. $500 322* Queen Victoria, fi rst type, 1855. Rim bruise under date, otherwise nearly fi ne. 329* Queen Victoria, second type, 1867. Very fi ne. $1,250 $450 Ex J. and J. Edwards Collection. 26 SYDNEY MINT HALF SOVEREIGNS 330* Queen Victoria, second type, 1868. Nearly extremely fi ne. $650 337* Queen Victoria, fi rst type, 1856. Nearly fi ne. $600 Ex J. and J. Edwards Collection. 331* Queen Victoria, second type, 1870. Nearly uncirculated/ uncirculated. $600 338* Queen Victoria, second type, 1861. Good very fi ne. $700 339 332* Queen Victoria, second type, 1861. Very good. Queen Victoria, second type, 1870. Considerable mint $200 bloom, extremely fi ne. $800 340* Queen Victoria, second type, 1866.