The Long Island Historical Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Memoriam Frederick Dougla

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection CANNOT BE PHOTOCOPIED * Not For Circulation Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection / III llllllllllll 3 9077 03100227 5 Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection jFrebericfc Bouglass t Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection fry ^tty <y /z^ {.CJ24. Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Hn flDemoriam Frederick Douglass ;?v r (f) ^m^JjZ^u To live that freedom, truth and life Might never know eclipse To die, with woman's work and words Aglow upon his lips, To face the foes of human kind Through years of wounds and scars, It is enough ; lead on to find Thy place amid the stars." Mary Lowe Dickinson. PHILADELPHIA: JOHN C YORSTON & CO., Publishers J897 Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Copyright. 1897 & CO. JOHN C. YORSTON Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection 73 7^ In WLzmtxtrnm 3fr*r**i]Ch anglais; "I have seen dark hours in my life, and I have seen the darkness gradually disappearing, and the light gradually increasing. One by one, I have seen obstacles removed, errors corrected, prejudices softened, proscriptions relinquished, and my people advancing in all the elements I that make up the sum of general welfare. remember that God reigns in eternity, and that, whatever delays, dis appointments and discouragements may come, truth, justice, liberty and humanity will prevail." Extract from address of Mr. -

Jackson Pollock & Tony Smith Sculpture

Jackson Pollock & Tony Smith Sculpture An exhibition on the centennial of their births MATTHEW MARKS GALLERY Jackson Pollock & Tony Smith Speculations in Form Eileen Costello In the summer of 1956, Jackson Pollock was in the final descent of a downward spiral. Depression and alcoholism had tormented him for the greater part of his life, but after a period of relative sobriety, he was drinking heavily again. His famously intolerable behavior when drunk had alienated both friends and colleagues, and his marriage to Lee Krasner had begun to deteriorate. Frustrated with Betty Parsons’s intermittent ability to sell his paintings, he had left her in 1952 for Sidney Janis, believing that Janis would prove a better salesperson. Still, he and Krasner continued to struggle financially. His physical health was also beginning to decline. He had recently survived several drunk- driving accidents, and in June of 1954 he broke his ankle while roughhousing with Willem de Kooning. Eight months later, he broke it again. The fracture was painful and left him immobilized for months. In 1947, with the debut of his classic drip-pour paintings, Pollock had changed the direction of Western painting, and he quickly gained international praise and recog- nition. Four years later, critics expressed great disappointment with his black-and-white series, in which he reintroduced figuration. The work he produced in 1953 was thought to be inconsistent and without focus. For some, it appeared that Pollock had reached a point of physical and creative exhaustion. He painted little between 1954 and ’55, and by the summer of ’56 his artistic productivity had virtually ground to a halt. -

The Frontier, November 1932

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana The Frontier and The Frontier and Midland Literary Magazines, 1920-1939 University of Montana Publications 11-1932 The Frontier, November 1932 Harold G. Merriam Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/frontier Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Merriam, Harold G., "The Frontier, November 1932" (1932). The Frontier and The Frontier and Midland Literary Magazines, 1920-1939. 41. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/frontier/41 This Journal is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Montana Publications at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Frontier and The Frontier and Midland Literary Magazines, 1920-1939 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. V'«l o P i THE1$III! NOVEMBER, 1932 FRONTIER A MAGAZINt Of THf NORTHWfST THE WEST—A LOST CHAPTER c a r e y McW il l ia m s THE SIXES RUNS TO THE SEA Story by HOWARD McKINLEY CORNING SCOUTING WITH THE U. S. ARMY, 1876-77 J. W. REDINGTON THE RESERVATION JOHN M. KLINE Poems by Jason Bolles, Mary B. Clapp, A . E. Clements, Ethel R. Fuller, G. Frank Goodpasture, Raymond Kresensky, Queene B. Lister, Lydia Littell, Catherine Macleod, Charles Olsen, Lawrence Pratt, Lucy Robinson, Claite A . Thom son, Harold Vinal, Elizabeth Waters, W . A. Ward, Gale Wilhelm, Anne Zuker. O T H E R STO R IE S by Brassil Fitzgerald and Harry Huse. -

The Jewish Experience in the Catskills

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2011 A Lost Land: The ewJ ish Experience in the Catskills Briana H. Mark Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Jewish Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Mark, Briana H., "A Lost Land: The eJ wish Experience in the Catskills" (2011). Honors Theses. 1029. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/1029 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Lost Land: The Jewish Experience in The Catskill Mountains By Briana Mark *********** Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of History Union College June 2011 1 Chapter One: Secondary Literature Review: The Rise and Fall of the Catskill Resorts When thinking of the great resort destinations of the world, New York City’s Catskill region may not come immediately to mind. It should. By the early twentieth century, the fruitful farmlands of Sullivan and Ulster Counties became home to hundreds of hotels and bungalow colonies that served the Jews of New York City. Yet these hotels were unlike most in America, for they not only represented an escape from the confines of the ghetto of the Lower East Side, but they also retained a distinct religious nature. The Jewish dietary laws were followed in most of the colonies and resorts, and religious services were also a part of daily life. -

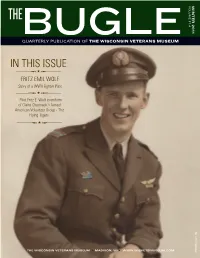

In This Issue

VOLUME 17:4 2011 WINTER IN THIS ISSUE FRITZ EMIL WOLF Story of a WWII Fighter Pilot Pilot Fritz E. Wolf in uniform of Claire Chennault’s famed American Volunteer Group - The Flying Tigers. THE WISCONSIN VETERANS MUSEUM MADISON, WI WWW.WISVETSMUSEUM.COM WVM Mss 2011.102 FROM THE DIRECTOR Wisconsin Veterans Museum. How soldier in the 7th Wisconsin. He may could it be otherwise? We are sur- have read about the Iron Brigade rounded by things that resonate in books, but the idea of advancing with stories of Wisconsin’s veterans. shoulder to shoulder in line of battle In this issue you will read stories under musket and cannon fire was about three men who, although sep- a relic of a far away past. Likewise, arated by time, embody commonly Hunt could never have imagined held traits that link them together Wolf’s airplane, let alone land- among a long line of veterans. We ing one on the deck of a ship. As a start with the account of the in- resident of Kenosha, Isermann may trepid naval combat flying ace Fritz have known veterans of Hunt’s Iron Wolf, a native of Madison by way of Brigade, but their ancient exploits Shawano, Wisconsin who flew with were long ago events separated by Claire Chennault’s Flying Tigers in more than fifty years from the Great China, and later with the US Navy. War. To a twentieth century man Wolf’s story is followed by the tragic engaged in WWI naval operations, account of an English immigrant, Gettysburg might as well have been John Hunt, who settled in Wiscon- Thermopylae. -

The Long Island Historical Journal

THE LONG ISLAND HISTORICAL JOURNAL United States Army Barracks at Camp Upton, Yaphank, New York c. 1917 Fall 2003/ Spring 2004 Volume 16, Nos. 1-2 Starting from fish-shape Paumanok where I was born… Walt Whitman Fall 2003/ Spring 2004 Volume 16, Numbers 1-2 Published by the Department of History and The Center for Regional Policy Studies Stony Brook University Copyright 2004 by the Long Island Historical Journal ISSN 0898-7084 All rights reserved Articles appearing in this journal are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life The editors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Office of the Provost and of the Dean of Social and Behavioral Science, Stony Brook University (SBU). We thank the Center for Excellence and Innovation in Education, SBU, and the Long Island Studies Council for their generous assistance. We appreciate the unstinting cooperation of Ned C. Landsman, Chair, Department of History, SBU, and of past chairpersons Gary J. Marker, Wilbur R. Miller, and Joel T. Rosenthal. The work and support of Ms. Susan Grumet of the SBU History Department has been indispensable. Beginning this year the Center for Regional Policy Studies at SBU became co-publisher of the Long Island Historical Journal. Continued publication would not have been possible without this support. The editors thank Dr. Lee E. Koppelman, Executive Director, and Ms. Edy Jones, Ms. Jennifer Jones, and Ms. Melissa Jones, of the Center’s staff. Special thanks to former editor Marsha Hamilton for the continuous help and guidance she has provided to the new editor. The Long Island Historical Journal is published annually in the spring. -

In England, Scotland, and Wales: Texts, Purpose, Context, 1138-1530

Victoria Shirley The Galfridian Tradition(s) in England, Scotland, and Wales: Texts, Purpose, Context, 1138-1530 A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature Cardiff University 2017 i Abstract This thesis examines the responses to and rewritings of the Historia regum Britanniae in England, Scotland, and Wales between 1138 and 1530, and argues that the continued production of the text was directly related to the erasure of its author, Geoffrey of Monmouth. In contrast to earlier studies, which focus on single national or linguistic traditions, this thesis analyses different translations and adaptations of the Historia in a comparative methodology that demonstrates the connections, contrasts and continuities between the various national traditions. Chapter One assesses Geoffrey’s reputation and the critical reception of the Historia between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries, arguing that the text came to be regarded as an authoritative account of British history at the same time as its author’s credibility was challenged. Chapter Two analyses how Geoffrey’s genealogical model of British history came to be rewritten as it was resituated within different narratives of English, Scottish, and Welsh history. Chapter Three demonstrates how the Historia’s description of the island Britain was adapted by later writers to construct geographical landscapes that emphasised the disunity of the island and subverted Geoffrey’s vision of insular unity. Chapter Four identifies how the letters between Britain and Rome in the Historia use argumentative rhetoric, myths of descent, and the discourse of freedom to establish the importance of political, national, or geographical independence. Chapter Five analyses how the relationships between the Arthur and his immediate kin group were used to challenge Geoffrey’s narrative of British history and emphasise problems of legitimacy, inheritance, and succession. -

Coney Island - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 8/3/11 11:29 AM

Coney Island - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 8/3/11 11:29 AM Coney Island Coordinates: 40.574416°N 73.978575°W From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Coney Island is a peninsula and beach on the Atlantic Ocean in southern Brooklyn, New York, United States. The site was formerly an island, but became partially connected to the mainland by landfill. Coney Island is possibly best known as the site of amusement parks and a major resort that reached their peak during the first half of the 20th century. It declined in popularity after World War II and endured years of neglect. In recent years, the area has seen the Coney Island peninsula from the air opening of MCU Park and has become home to the minor league baseball team the Brooklyn Cyclones. The neighborhood of the same name is a community of 60,000 people in the western part of the peninsula, with Sea Gate to its west, Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach to its east, and Gravesend to the north. Contents 1 Geography 2 History 2.1 Etymology Aerial view of the beach at Coney 2.2 Resort Island[1] 2.3 Development 3 Demographics 4 Communities 5 Education 6 Transportation 7 Amusement parks 7.1 Rides 7.2 Rides of the past 7.3 Other venues 7.4 Beach 7.5 Other events Coney Island from space 8 In entertainment 9 References 10 Further reading 11 External links Geography Coney Island is the westernmost part of the barrier islands of Long Island, about 4 miles (6.4 km) long and 0.5 miles (0.80 km) wide. -

Spring 2015 CUES Internet at the Speed of Whoa

OPERAVolume 55 Number 05 | Spring 2015 CUES Internet at the speed of whoa. XFINITY® Internet delivers the fastest and most reliable in-home WiFi for all rooms, all devices, all the time. To learn more call 866-620-9714 or visit comcast.com Restrictions apply. Not available in all areas. Features and programming vary depending on area and level of service. WiFi claims based on April and October 2013 study by Allion Test Labs, Inc. Actual speeds vary and are not guaranteed. Reliably fast speed based on February 2013 FCC Broadband Report. Call for restrictions and complete details. ©2014 Comcast. All rights reserved. All trademarks are property of their respective owners. DIE WALKÜRE APRIL 18, 22, 25, 30 MAY 3 SWEENEY TODD APRIL 24, 26, 29 MAY 2, 8, 9 PATRICK SUMMERS PERRYN LEECH ARTISTIC & MUSIC DIRECTOR MANAGING DIRECTOR Margaret Alkek Williams Chair ADVERTISE IN OPERA CUES Opera Cues is published by Houston Grand Opera Association; all rights reserved. Opera Cues is produced by Houston Grand Opera’s Communications Department, Judith Kurnick, director. Director of Publications Laura Chandler Art Direction / Production Pattima Singhalaka Contributors Kim Anderson Paul Hopper Perryn Leech Elizabeth Lyons Patrick Summers For information on all Houston Grand Opera productions and events, or for a complimentary season brochure, please call the Customer Care Center at 713-228-OPERA (6737). Houston Grand Opera is a member of OPERA America, Inc., and the Theater District Association, Inc. Find HGO online: HGO.org facebook.com / houstongrandopera twitter.com / hougrandopera instagram.com/hougrandopera Readers of Houston Grand Opera’s Opera Cues magazine are the Mobile: HGO.org most desirable prospects for an advertiser’s message. -

Mayor's Office of Arts, Tourism and Special Events Boston Art

Mayor’s Office of Arts, Tourism and Special Events Boston Art Commission 100 Public Artworks: Back Bay, Beacon Hill, the Financial District and the North End 1. Lief Eriksson by Anne Whitney This life-size bronze statue memorializes Lief Eriksson, the Norse explorer believed to be the first European to set foot on North America. Originally sited to overlook the Charles River, Eriksson stands atop a boulder and shields his eyes as if surveying unfamiliar terrain. Two bronze plaques on the sculpture’s base show Eriksson and his crew landing on a rocky shore and, later, sharing the story of their discovery. When Boston philanthropist Eben N. Horsford commissioned the statue, some people believed that Eriksson and his crew landed on the shore of Massachusetts and founded their settlement, called Vinland, here. However, most scholars now consider Vinland to be located on the Canadian coast. This piece was created by a notable Boston sculptor, Anne Whitney. Several of her pieces can be found around the city. Whitney was a fascinating and rebellious figure for her time: not only did she excel in the typically ‘masculine’ medium of large-scale sculpture, she also never married and instead lived with a female partner. 2. Ayer Mansion Mosaics by Louis Comfort Tiffany At first glance, the Ayer Mansion seems to be a typical Back Bay residence. Look more closely, though, and you can see unique elements decorating the mansion’s façade. Both inside and outside, the Ayer Mansion is ornamented with colorful mosaics and windows created by the famed interior designer Louis Comfort Tiffany. -

The Industrialization of Long Island City (Lic), New York

EXPLORING URBAN CHANGE USING HISTORICAL MAPS: THE INDUSTRIALIZATION OF LONG ISLAND CITY (LIC), NEW YORK by Elizabeth J. Mamer A Thesis Presented to the FACULTY OF THE USC GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE (GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY) August 2015 2015 Elizabeth J Mamer DEDICATION In memory of my father, who loved and collected old maps. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Karen Kemp for her continued guidance as I worked my way through this research. Her patience and instruction were invaluable. Thank you as well to my mom and sister for their constant support throughout this process. A great thanks to Florence, whose boundless and persistent spirit motivated me. And finally, to Spencer, for both encouraging me and putting up with me. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii LIST OF TABLES iii LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS vi ABSTRACT vii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Motivation 2 1.2 Study Area 3 1.3 Research Goals 5 CHAPTER 2: BACKGROUND AND LITERATURE REVIEW 7 2.1 Historical GIS 7 2.2 Historical Narrative: The Urban Development of LIC 8 2.2.1 Pre-industrialization 9 2.2.2 Industrialization 10 2.2.3 Transportation Expansion 12 2.2.4 Residential Changes 14 2.3 Trends in Industrial Societies 15 CHAPTER 3: DEVELOPING THE DATASET 17 3.1 Historical Maps as Data Sources 17 3.2 Georeferencing 19 3.3 Digitization 22 3.4 Data Organization 26 3.5 Assign Shifts 30 CHAPTER 4: EXPLORING THE STORIES 33 4.1 Enumerating -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website.